Glenn Hubbard

Every successful team should have a player like Glenn Hubbard. Though undersized, he played with a tremendous amount of heart and always left all his energy on the field. Teammates recognized his value. Hubbard hit just .244 over his 12 seasons in the majors, but he had some pop in his bat, connecting for 70 home runs in 1,354 games.

Every successful team should have a player like Glenn Hubbard. Though undersized, he played with a tremendous amount of heart and always left all his energy on the field. Teammates recognized his value. Hubbard hit just .244 over his 12 seasons in the majors, but he had some pop in his bat, connecting for 70 home runs in 1,354 games.

Though overshadowed by Manny Trillo and then Ryne Sandberg, he was also one of the more talented fielders among NL second basemen during the decade of the 1980s. Hubbard was a born fighter who never let his small stature – listed at 5-feet-9 (though some media accounts sometimes referred to him as closer to 5-feet-7) – impede his success on the baseball diamond.

Glenn Dee Hubbard was born on September 25, 1957, at the US Air Force Base in Hahn, Germany, to Harry Hubbard, a member of the Air Force, and his wife, Nancy. The family also included four brothers (Steven, Bart, Keven, and Brad) and a sister (Cathy).

The Air Force life led the Hubbard family to reside in 12 different cities before settling down in Ogden, Utah, about 40 miles north of Salt Lake City.1 Young Glenn first played baseball in Taiwan when his father was stationed there. Though he didn’t play in the renowned Taiwan Little League, he did play games against some of their teams and noticed how seriously those teams took the game.2

His father had a strong influence over the way Glenn played. “I’ve never had to overcompensate because of my size, but playing hard is just always the way I was taught to play,” Hubbard said in 1983. “My dad always taught me to give it all I’ve got and I’ve always kept that in mind. I’ve seen guys with twice my ability in the minor leagues and they didn’t give enough and they’re not around anymore.”3

Hubbard was also influenced early in baseball by the play of Cincinnati Reds All-Star Pete Rose.

“Rose is my kind of player,” said Hubbard in 1977. “I try to pattern my playing style after him. But after all, there is only one Pete Rose.”4

While at Ben Lomond High School in Ogden, Utah, Hubbard played football, basketball, and baseball and was on the wrestling squad. He excelled in basketball and baseball. He was twice named MVP of the baseball team and was extremely competitive in the Utah State Wrestling Tournament at the 145-pound weight class. As a senior in 1975 he batted. 461.5

In high school Hubbard played shortstop, but felt that the major-league scouts didn’t see a future for him at that position. “When I signed, I was moved to second base because of my size. I really don’t think size has too much to do with becoming a major leaguer,” said Hubbard three years after being drafted.6

In the June 1975 amateur draft, Hubbard was selected out of high school in the 20th round (pick number 473) by the Atlanta Braves – 11 picks ahead of southpaw pitcher John Tudor, who would play 12 seasons (1979-1990) in the big leagues. Out of all the Braves’ draft picks in 1975, only two would play more than 100 games with Atlanta: Hubbard and their second-round pick, outfielder Larry Whisenton. In the 22nd round in 1975, the Braves drafted pitcher Nate Snell, who would pitch in 104 games from 1984 to 1987 with the Baltimore Orioles and the Detroit Tigers.

Hubbard’s first stop in his professional baseball journey was in rookie ball with the Kingsport (Tennessee) Braves during the summer of 1975. In 53 games he batted. 287 and led the team with a .421 on-base percentage.

Hubbard started the 1976 season with Kingsport, and after hitting .294 in 37 games, he was promoted to the Greenwood (South Carolina) Braves of the Western Carolina League (Class A). His bat stayed hot in Greenwood: he batted .318, with a .404 on-base percentage and a .492 slugging average.

The young prospect had some major struggles in his personal life very early in his minor-league career. Hubbard’s first marriage ended by the time he was 19. In an interview with the South Florida Sun Sentinel in February 1984, he admitted this was one of the most difficult moments of his life. However, things got better while he was playing at Greenwood. He started chatting casually with Lynn Wells, a waitress at a local Pizza Hut. On their first date she read him verses from the Bible. They were married in 1978 and she influenced him to become a born-again Christian. They had three sons: Jeremy, Matthew, and Daniel,7 and as of 2022 resided in Stone Mountain, Georgia since the mid-1980s.

In 1977 Hubbard got off to a hot start in Greenwood, batting .385 over 45 games. That led to a promotion to Double-A Savannah. He finished out the season there but hit only .225. Despite his struggles at Double A, the Braves promoted him again; he started the 1978 season with the Richmond Braves in Triple A.

Very early in his minor-league career, coaches recognized Hubbard’s fielding skills, including former Yankees and Braves third baseman Clete Boyer. A renowned glove man in his playing days, Boyer was then a minor-league fielding instructor for the Braves. “First time I saw him in the Instructional League … I knew the kid was a natural,” said Boyer. “No one can take credit for teaching Hubbard to field. God gave him all the tools. I played eight years with Bobby Richardson with the New York Yankees, and Hubbard reminds me very much of him. He wants to learn everything there is to know about this game, and you find few players with his attitude today.”8

Another minor-league coach who helped Hubbard to develop in the minors was Forrest “Smoky” Burgess. At that time Burgess held the major-league record for career pinch hits with 145.9 Burgess tried to help Hubbard become more patient at the plate. “He’s a good hitter, got good power, great desire and is a good glove man. … His size (5-foot-7) may be against him but his attitude tells me he’s a prospect,” said Burgess about Hubbard.10

Once Hubbard reached Triple A, his bat exploded. For the first few months of the 1978 season, he led the International League in batting average and home runs. Future Boston Red Sox manager Joe Morgan, who was managing at Richmond rival Pawtucket in 1978, was very impressed by Hubbard’s skills. “The best player in the league. He can hit and he’s a great competitor. He fields the ball kinda funny, but so far this year I haven’t seen him miss anything. He’s got a great future,” said Morgan in an interview with The Sporting News.11

Hubbard’s production at Richmond led to a big-league call-up in the second week of July. He replaced shortstop Pat Rockett, who was struggling at the plate with a .141 average. At the time of his summons, Hubbard was batting .336 with 14 home runs with Richmond.

He made his big-league-debut on July 14, 1978, against the Philadelphia Phillies. The game featured starting pitchers who would go on to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Steve Carlton and Phil Niekro. On this day, the knuckleballer Niekro would get the better of Lefty, throwing a four-hitter and leading the Braves to a 7-2 win. Hubbard singled off Carlton in his first major-league plate appearance.

Things did not progress smoothly for Hubbard. About a week after his debut, he injured his elbow and missed a month of action. When he came off the disabled list, though, he really began to hit as he had in Richmond. His batting average peaked at .311 on September 3. However, he went 1-for-21 during the Braves’ last five games of the season, and his batting average dipped over 30 points; he finished his debut season batting .258.

In 1979 Hubbard struggled at the plate. He was batting around .220 at the end of July, and was demoted to Richmond on July 31. By then the Braves had handed the second-base duties to utility player Jerry Royster. At Richmond, Hubbard batted .336 in 34 games before being recalled to Atlanta in the middle of September. After returning to the Braves, he finished the season going 8-for-20.

Hubbard never let one bad game or season get him down. “If you sit down after each game and try to figure out why something is happening, you’d go crazy,” he said. “You can go from goat to hero fast.”12

The next season, 1980, manager Bobby Cox and the Braves brain trust decided to stay with Royster (whom they had given a five-year contract) at second base. Hubbard returned to Richmond for the third time in three years. Despite the nice contract, Royster proved to be a liability for the Braves at second base, committing 13 errors during the first two months of the season. This led the Braves to recall Hubbard from Richmond on May 31. At the time, Hubbard was hitting .315 at Triple A. He would never play in the minor leagues again.

From that point, the Braves committed to making Hubbard their second baseman. In June 1980 he batted .310 with 3 home runs and a .531 slugging average. More importantly, the Braves went 64-54 over the rest of the season, posting a 60-53 record when Hubbard started at second base.

Hubbard set a Braves record in 1981. His .991 fielding percentage broke the previous single season record at second base set by Frank Bolling (.989) in 1962,13 when the team still played in Milwaukee. Hubbard made only 5 errors in 537 chances during the strike-shortened ’81 season.

In 1982 Joe Torre (who’d managed the New York Mets from 1977 to 1981) replaced the fired Bobby Cox. The Braves won their first 13 games to start the season, a new major-league record.14 This hot start helped them win their first NL West Division title since 1969. Hubbard also got off to a strong start at the plate. When he went 11-for-23 during the first five days in May, his batting average for the season peaked at .297. Though his bat cooled off later, he went on to tie his career high in home runs to that point with nine. His 59 RBIs were also a new personal best, which he would top the following season. He scored 75 runs, a mark he would never equal. He also led all NL batters and all major-league second basemen in double plays turned and sacrifice hits in 1982.

But the Braves couldn’t get past the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League Championship Series, getting swept in three games. In his first postseason appearance, Hubbard went 2-for-9 at the plate.

The Braves rewarded Hubbard’s efforts in the offseason with a five-year contract worth close to $4 million. His teammates also recognized how valuable he was to their success on the field and how he gave so much of himself every day – especially his ability to play through injuries.

“You can’t measure a guy’s value when he’s doing all those things and he’s playing with nagging injuries,” said Braves captain and third baseman Bob Horner in 1983. “You take Hub out of our lineup and who knows what we would have done.”15

“People don’t realize when a guy is playing with all the injuries,” center fielder Dale Murphy said. “But when you watch a guy put a shoe on over a sore toe or when he lifts his arm with a sore shoulder, you see the pain on his face. He’s invaluable.”16

In 1983 Hubbard remained successful with the bat. During a strong first half of the season, he hit .300 with 5 home runs and 37 runs batted in. This earned him selection as a reserve in the All-Star Game at Comiskey Park. During the game he singled in his only plate appearance after coming on for Steve Sax.

Hubbard finished the 1983 season with career-best totals in homers (12) and RBIs (70). The Braves won 88 games in 1983 but finished in second place in the division, three games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Hubbard’s playing career peaked during the 1982 and 1983 seasons. After that, he hit a few bumps. In 1984 he suffered a significant shoulder injury during a bench-clearing brawl with the San Diego Padres, in which he scuffled with their third baseman, Graig Nettles.

The Braves had a new manager in 1985, Eddie Haas, who replaced the fired Torre. Haas didn’t really give Hubbard a fair shot when he took over; he tried to replace him at second with Paul Zuvella, who had played for Haas in the minors. Luckily for Hubbard, Haas didn’t last a full season as Atlanta’s skipper. He was fired after 121 games and was replaced by Bobby Wine on an interim basis.

Former Pittsburgh Pirates manager Chuck Tanner was hired to manage the Braves in 1986. Tanner was a much more positive leader and communicator than Haas, but over the next two years a pattern developed: he started Hubbard consistently but often pinch-hit for him later in the game in 1986 and 1987.

“Although I played a lot, whenever the game was on the line they took me out,” Hubbard said. “They pinch-hit for me 40 times with men either on base or in scoring position. Things like that just made me feel like I wasn’t part of the team. I developed a bad attitude.”17 This frustrated Hubbard and he welcomed becoming a free agent after the 1987 season.

In January 1988 Hubbard signed with the Oakland Athletics, who also traded for starting pitcher Bob Welch and power-hitting outfielder Dave Parker that offseason. Hubbard’s tenure with the A’s got off to a rough start when he was hit by a pitch in the face during a spring-training game, which caused him to start the 1988 season on the disabled list.

Hubbard made his debut with the Athletics on April 15, batting eighth, ahead of shortstop Walt Weiss. He collected a single in four at-bats in an 11-3 loss to the Chicago White Sox. One of the reasons Hubbard was signed by Oakland was to help their defense up the middle. However, his 1988 season was hampered by a hamstring injury, which caused him to miss over 50 games, including the American League Championship Series vs. the Boston Red Sox.

His hamstring healed enough to allow Hubbard to play in four World Series games against the Dodgers. In Game One, he went 2-for-4 before Kirk Gibson hit his legendary home run in the bottom of the ninth inning to lead the Dodgers to a 5-4 victory. Hubbard went 3-for-12 in the four Series games he played.

Coming into spring training in 1989, Hubbard wasn’t guaranteed a starting spot. He was in a tough battle for his position with Mike Gallego and Tony Phillips, both of whom were considered better hitters than Hubbard but not in his class when it came to fielding. Hubbard ending up winning the job, but A’s manager Tony La Russa kept using different lineups that meant inconsistent playing time. Hubbard started to hit efficiently in late May and early June, getting his average up to .270, but that was the best it would get. Oakland released Hubbard on July 31, when he was hitting .198.

After his playing days were over, Hubbard went into coaching. He was a hitting coach in the minor leagues for the Braves between 1991 and 1998. From 1999 to 2010, he was called back up to the Braves to become the first-base coach for Bobby Cox. Starting in 2014 he has been a bench coach in Single-A ball, most recently with the Columbia Fireflies, a Kansas City Royals affiliate in the Carolina League.

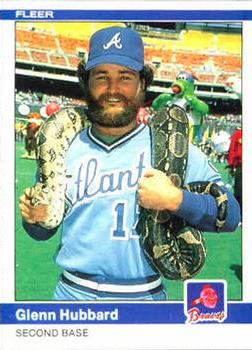

For many people, Hubbard is best remembered for having one of the most renowned baseball cards in history. His 1984 Fleer card has him posing on the field at Philadelphia’s Veterans Stadium with a large boa constrictor around his neck and a smile on his face. The snake was at the ballpark that day as part of a pregame ceremony in 1983 for a birthday celebration for the Phillies mascot, the Phillie Phanatic.

In 2021, an article on MLB.com by Michael Clair, “The True Story Behind Glenn Hubbard’s Snake Card,” detailed the history of the card and Hubbard’s personal feelings about it – which weren’t always positive.

“A guy had a snake on the field. And I grabbed a photographer and I said, ‘Hey can I get my picture taken with this snake?’ So I put it around my neck. Get the picture taken. He sent me an 8 by 10. And that’s all I know about it,” said Hubbard about the famous picture.18

What Hubbard didn’t know was the photographer was a freelancer who did some work for the Fleer Corporation. In spring training 1984 he was shocked when a asked him to sign a Fleer card with the snake around his neck. It took Hubbard many years before he was comfortable with his image on that popular item.

In 2016, while he was a coach with the Lexington Legends of the South Atlantic League, the team did a promotion at the ballpark commemorating that Fleer card. The Legends had a “Glenn Hubbard Bobblehead Giveaway,” with him in a Legends uniform and a snake around his neck.

Looking back at posing for the picture with the snake, Hubbard didn’t express any regrets.

“I would, I’d do it again,” Hubbard said. “A lot of people like that card. I look at it, look at my long hair, look at the beard. I mean, it was just really full and oh, man, the card is perfect.”19

Last revised: August 12, 2022

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Sources

Websites

www.facebook.com/Benlomondalumniassociation/

Newspapers

The Sporting News

Birmingham (Alabama) Post-Herald

Kingsport (Tennessee) Times

Ft. Lauderdale Sun Sentinel

Atlanta Constitution

Boston Globe

Charlotte Observer

Greenwood (South Carolina) Index-Journal

Macon (Georgia) News

Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call

Ogden (Utah) Standard Examiner

West Palm Beach Post

Notes

1 Bill Carter, “Hubbard: ‘Little Big Man on Ball Field’” Alexandria (Louisiana) Town Talk, March 16, 1984: B1.

2 Bill Bank, “Little Big Man – Glenn Hubbard Ace at Second Base Keeps the Braves’ Competitive Fire Burning with His True Grit,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 7, 1982: 1C.

3 Jay Lawrence, “Hubbard Wants to Be Bigger Hit with Braves,” West Palm Beach Post, March 6, 1983: 417.

4 “Former Ben Lomond Star Hubbard Called Up by Atlanta Braves,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, December 21, 1977: 51.

5 Bill Lane, “Meet the Braves,” Kingsport (Tennessee) Times, June 29, 1976: 3B.

6 John Cargile, “Want to Go Pro? Top Skills a Must,” Birmingham Post-Herald, August 11, 1978: 16.

7 Joseph Person, “Home Has New Meaning to Hubbard,” Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, February 25, 1999: 1C.

8 Jesse Outlar, “Glenn Hubbard Blossoms into All-Star Player,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 13, 1982: D1.

9 As of 2022 Lenny Harris held the record with 212 pinch hits.

10 Whitey Kelley, “Smoky Burgess ‘Best Pinch-Hitter in History,’” Charlotte Observer, June 13, 1977: 12A.

11 Int. League Items, The Sporting News, July 22, 1978: 42.

12 Dave Kindred, “Novel on Braves Season Still in the Early Chapters,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 26, 1984: E1.

13 2021 Atlanta Braves Media Guide, 359. Mark Lemke in 1994 had a .994 fielding percentage to break Hubbard’s 1981 record.

14 The 1981 Oakland A’s under Billy Martin won 11 straight games. In the NL, the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers and the 1962 Pittsburgh Pirates each won their first 10 games.

15 Lawrence, “Hubbard Wants to Be Bigger Hit with Braves.”

16 Lawrence.

17 Ed Grisamore, “For the Braves, Hubbard’s Been an Answered Prayer,” Macon Telegraph, June 20, 1987: S-1.

18 Michael Clair, “The True Story Behind Glenn Hubbard’s Snake Card.” https://www.mlb.com/news/glenn-hubbard-s-fleer-snake-card-story-revealed.

19 Clair.

Full Name

Glenn Dee Hubbard

Born

September 25, 1957 at Hahn, (Germany)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.