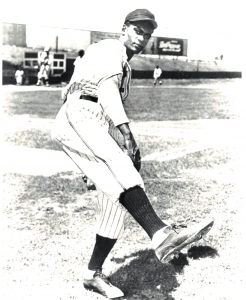

Jim LaMarque

“LaMarque was probably the most unassuming of all the Monarch players. … He didn’t stand out. And he liked it like that. Lefty quietly went about his business.” – Ray Doswell, curator, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum1

“LaMarque was probably the most unassuming of all the Monarch players. … He didn’t stand out. And he liked it like that. Lefty quietly went about his business.” – Ray Doswell, curator, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum1

Jim LaMarque, who like so many southpaws was nicknamed Lefty, said he almost quit in 1942, his first year in professional baseball. He was 21 years old when the season began, and said he became homesick and tired of being the youngest player on the team. Some taunted him by calling him Dizzy’s Boy, in reference to Dizzy Dismukes, who scouted him and recruited him to the Monarchs. One time, while playing in St. Louis that season, LaMarque was only 72 miles from home. He related how his “escape plan” was foiled: “So I stashed my bag under the bed and hid until the team bus was gone. Just as I was getting the bag out, Satchel Paige walked in. He was our top pitcher, and I had been living with him since I joined the team. He drove his own automobile to the games, and he told me just to throw that bag in his car and to get in and hurry up about it. So I did. And I’m awfully glad.”2

James Hardin LaMarque Jr. was born on July 29, 1920, in Potosi, Missouri, a farming town about 75 miles southwest of St. Louis, to James and Martha (Casey) LaMarque. The third of six siblings who grew up on the family farm, he had two older sisters and three younger brothers.

His first marriage was at age 19 just before joining the Monarchs. LaMarque was 6-feet-2 and weighed 182 pounds.3 The 1940 census lists LaMarque as a laborer with an eighth-grade education, working odd jobs. He married Theresa Stanley, the first of his two wives, on August 9, 1939. Their first child, Joyce, was born in December 1940.4

Before LaMarque signed with the Monarchs, he said, he had played “just sandlot ball and baseball with a team that was from where I was from. It was a white team.”5 When the Potosi Lions, a White team, needed help, they wanted to add him as their primary pitcher. As LaMarque recalled, “We had a black club and a white club. The white club’s pitcher hurt his arm some kind of way, so they asked me – a black boy – if I would pitch for the white club. We only played a few games a season, but I played two seasons with them and we won most of our games. The Kansas City Monarchs heard of me and they wondered why a black boy would be pitching on an all-white team, so they got in touch with me and I came to the Monarchs in 1942, and I guess, I left them in 1950.”6

LaMarque saw limited action, especially in official Negro American League games, during much of his 1942 debut season, because the team’s pitching staff included two future Hall of Famers, Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith, as well as Jack Matchett and Booker McDaniel. He pitched in some preseason games, throwing five shutout innings against the Cincinnati-Cleveland Buckeyes on April 14 before turning the game over to Paige.

LaMarque appeared primarily in exhibition games, but he did pitch to a 2-0 record and 3.46 ERA in NAL play. He pitched a couple of exhibition games in May in Council Bluffs and Sioux City, Iowa, before shutting out the Birmingham Black Barons, 1-0, at Ruppert Stadium on the last day of the month.

He pitched against the Memphis Red Sox on July 10 in Wichita Falls, Texas, and on July 16, in front of the largest gross gate at City Stadium in St. Joseph, Missouri, LaMarque went seven strong innings, getting the 4-3 win over the Memphis Red Sox. He was beginning to make a name for himself; in an article previewing the Monarchs coming to Yankee Stadium to play the New York Cubans in early August, the New York Age referred to him as “the Southpaw strikeout kid, ‘Jimmie’ LaMarque.”7 In the St. Joseph game, he contributed with the bat. Leading off the seventh inning he drew a walk, stole second, moved to third on a passed ball, and scored on a triple by Newt Allen.8 In between occasional starts, LaMarque worked in relief, one such standout effort coming against the Ethiopian Giants in Toledo on August 27. Paige threw two hitless innings and LaMarque pitched seven scoreless innings in a game the Monarchs won, 1-0.

Exhibition games were crucial to the financial success of teams like the Monarchs, and LaMarque was building a solid reputation as an integral part of a standout pitching staff.

During the 1942 Negro World Series, the Monarchs and Homestead Grays took a six-day break between weekend Games Three and Four. The Grays filled the time with games against the Newark Eagles, Philadelphia Stars, and Baltimore Elite Giants. The Monarchs played one, in Louisville on September 18, against the Cincinnati Clowns. The game ran 13 innings, and LaMarque went the distance for a 1-0 victory.9

LaMarque spent most offseasons working in Pacific, Missouri, at the Pioneer Silica Products factory.10 He missed the 1943 season after breaking his pitching arm in a workplace accident, but he rejoined the Monarchs in 1944.11 He was with the team from spring training in Houston through the season, but the statistical record does not reflect as much action. He is shown with a 1-0 record in 1944 (the Howe News Bureau statistics show him as 2-3). He sometimes played other positions; playing first base on July 20, he hit a two-run homer in the bottom of the sixth to get the Monarchs on the scoreboard.12 He worked in both games of a June 25 doubleheader against the Homestead Grays at Washington’s Griffith Stadium.13

LaMarque got more and more key assignments as the Monarchs continued to be one of the best teams in the league, always drawing good-sized crowds during league and exhibition games. Even during World War II, the Monarchs often “sold out or came close to selling out most of their home games at 17,000-seat Ruppert Stadium (which eventually was renamed Municipal Stadium).” They also continued to be a popular draw on the road. LaMarque said, “Everywhere we went, people came to see us. … Everyone wanted to see the Monarchs.”14

The 1945 Monarchs, for whom Jackie Robinson played, went 43-32 and finished second to the 59-15 Cleveland Buckeyes. LaMarque’s 59 strikeouts were second on the team to Bookie McDaniel’s 113.

The June 22 Brooklyn Eagle noted LaMarque in a headline, reporting him as undefeated to that point.15 Satchel Paige had thrown five shutout innings against the Philadelphia Stars in front of 14,000 fans at Yankee Stadium on June 18; LaMarque worked the last four innings without allowing a hit.16 The July 8, 1945, Kansas City Star said he was “undefeated in the loop.”17 In late July, LaMarque was reported to have won eight consecutive games.18 Josh Gibson’s two-run homer into the upper deck of Shibe Park’s center-field stands beat him, 3-2, in Philadelphia against the Homestead Grays on August 7.19 In NAL play, however, he was still reported as “undefeated in league competition” as late as August 22.20 He is listed as finishing the season 5-2 in 73⅔ innings of pitching in league games. He pitched in after-season games as well, beating the Cincinnati Clowns, 6-0, with a six-hitter on September 18.21

The 1946 season was a big year for both the Monarchs and LaMarque. He had begun to see increased action in league games in 1945 and now was counted on as a more regular contributor. When he was discovered by the Monarchs on the amateur fields in Potosi, LaMarque averaged 12 strikeouts per game; in early 1946, he was averaging seven per game. NAL competition was obviously tougher than semipro squads and LaMarque had suffered the broken-arm setback, but he was holding his own against opponents.22 He threw a complete game on July 21, going nine innings against the Cincinnati-Indianapolis Clowns and surrendering five hits and two runs, giving those up in the top of the ninth to lose a heartbreaker.23 One noteworthy win was against the Memphis Red Sox, 3-1, in the six-inning second game of a Sunday doubleheader on August 25, holding Memphis to three hits.24

The 1946 Monarchs captured the NAL pennant with a 50-16-2 league record (55-26-2 overall), claiming both the first- and second-half league titles. They faced the Newark Eagles in one of the best Negro League World Series ever played. The Series was tied when LaMarque started Game Three in Kansas City on September 22. He struck out eight while walking three in a complete-game effort. Although he allowed Newark to score five runs, he was more than adequate to the task on this day as his teammates clobbered the Eagles’ pitching in a 15-5 triumph. The Monarchs had a three-games-to-two lead when LaMarque again took the hill in Game Six. This time, he never got out of the first inning. After the Monarchs roared out to a 5-0 lead in the top of the first, LaMarque walked three consecutive batters and then allowed two singles that resulted in four runs for the Eagles. LaMarque did not see the mound again in the World Series as the Eagles won Game Six by a 9-7 score and took the Series with a 3-2 victory in Game Seven.25

After the World Series, LaMarque joined the barnstorming Satchel Paige’s All Stars for a tour. Paige and LaMarque combined efforts but still came up short, 3-2, against Bob Feller’s All-Stars in an October 12 game at Council Bluffs, Iowa, in front of a “shivering crowd” of 4,000.26

LaMarque then headed to a warmer land – Cuba, where he pitched for the Habana Leones. Habana finished 40-26, which was only good enough for second place, two games behind Almendares. LaMarque compiled a 7-6 record, pitching two complete games, with 44 strikeouts in 89 innings pitched; he walked 59.27

By 1947, the year that Jackie Robinson broke the White major leagues’ color barrier, LaMarque was playing year-round. Now that Blacks were being signed for the White leagues, LaMarque was bound to gain the notice of some scouts. Indeed, at one time he reportedly had an opportunity to sign with the Yankees, but negotiations fell through. LaMarque explained the situation:

“There was a time. I used to belong to the Monarchs which was owned by a man named Wilkinson at first, and his partner was named Tom Baird. I talked to the chief scout of the Yankees at that time. He was named Tom Greenwade. After Tom Baird found out that they might want me, he hiked the price on me, so Greenwade told me ‘At your age, I can’t pay this kind of money.’ So, I didn’t go with him.”28

Even without a shot at making the White majors, LaMarque continued to thrive on constant work. He had come a long way since his broken arm, noting, “I’ve played several seasons of winter ball and my arm feels great.”29 He had a strong season in 1949. One notable early game was on May 25 when the Monarchs swept a doubleheader from Memphis at Kansas City’s Blues Stadium; LaMarque won the first game, 4-2, while going 3-for-4 at the plate with two doubles.30 One win that must have been especially satisfying for the native of nearby Potosi was playing in St. Louis’s Sportsman’s Park and throwing a three-hitter to beat the Memphis Red Sox, 6-0, on August 28.31

The 52-32 Monarchs finished second in the league in 1947, behind the 42-12 Cleveland Buckeyes, who played far fewer games.32 Seamheads shows his record for the season as 8-3 with 80 strikeouts, more than twice as many as any other Monarchs pitcher.33

After the season, LaMarque rejoined the Habana Leones. Habana won the league title with a 39-33 record, finishing one game ahead of Almendares. LaMarque was one of three Habana pitchers who finished with double-digit win totals as he went 11-7 with 62 strikeouts and a 3.93 ERA in 128 innings pitched.34

After returning from Cuba, LaMarque found additional success with Kansas City in 1948. The Monarchs finished 60-30-2 and won the NAL’s first-half championship. Connie Johnson recalled, “Sometimes it was hot here in Kansas City. Lefty was the only one who could go nine innings. The rest of us could only go three innings. During the games,” Johnson said, “Lefty would be drenched in sweat. Between innings, he placed his feet in a bucket of ice water. It was so hot, by the time he pulled his feet out, his feet were dry.”35

That season, LaMarque made his first appearance in the annual East-West All-Star Games. He pitched in both games, a total of five innings, giving up five hits. On August 22 at Comiskey Park in Chicago, he combined with Birmingham’s Bill Powell and Chicago’s Gentry Jessup to shut out the East All-Stars, 3-0. LaMarque pitched innings three through six and gave up two hits while walking none.36 The second All-Star Game in 1948 was played at Yankee Stadium two days later. This time, LaMarque entered the game in the top of the seventh inning with his West team trailing, 4-1. He pitched two innings in which he surrendered three hits and the West’s final two runs, both of which were unearned, as the East lost, 6-1.37

On September 11, 1948, the Monarchs met the Birmingham Black Barons in the American East playoffs. LaMarque got the ball in Game One. He held the Barons hitless until the fifth but the Monarchs lost the opener, 5-4. LaMarque returned to the hill in Game Three, relieving starter Connie Johnson. He held the Barons close but could not gain a win for the Monarchs. With thr Monarchs down three games to none, Buck O’Neil turned to his ace to take the mound in Game Four. Tying up the Barons hitters, LaMarque also delivered at the plate, hitting a sacrifice fly in the eighth inning and adding a run to give the Monarchs a 3-1 lead. In doing so LaMarque gained his first victory in the Series. Game Six saw LaMarque score the winning run, as a pinch-runner. The Monarchs won, 5-4. Game Seven saw him work the fourth time in eight games. He gave up runs in the fourth, fifth, and eighth innings before being lifted but the damage had been done. The Barons moved on to a showdown with the Homestead Grays.

After the season, LaMarque pitched with Paige’s All-Stars once more. On October 25 he came into the game in relief and shut down Gene Bearden’s All-Stars, 4-3, at Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field. With the bases loaded and one out, he got Al Zarilla to hit the ball back to him and threw home to start a 1-2-5 game-ending double play.38

After the 1948 season, LaMarque joined the Santurce Crabbers in Puerto Rico, where he spent the next two offseasons (1948-49 and 1949-50). On February 15, 1949, LaMarque hurled a six-hit shutout in Game Four of the league finals at Mayagüez. He blanked a powerful lineup featuring Luke Easter, Alonzo Perry, Artie Wilson, Wilmer Fields, and Johnny Davis.39 Over those two seasons, he went 13-10 with a 2.59 ERA, pitching 219 innings.40 His catcher with the Monarchs in 1946-48 and in Santurce was Earl Taborn, a fellow resident of Potosi.

By the 1949 season, LaMarque was seen as one of the best pitchers in the Negro Leagues and was consistently at the top in most pitching categories. He finished his final full season with the Monarchs with a 13-7 record, 96 strikeouts, and a 3.08 ERA over 196 innings.41 His numbers garnered him another selection to the West team for the All-Star Game at Comiskey Park on August 14. LaMarque pitched the ninth inning, giving up one hit, as the East won, 4-0.42 During the season Monarchs co-owner Tom Baird interviewed LaMarque about his biggest thrill in baseball. “I struck out Josh Gibson 3 times in one game,” he responded, “But next time up Gibson hits the ball out of the park with plenty to spare.”43

The 1950 season was LaMarque’s last campaign with the Monarchs. In addition to pitching, he was often used as a pinch-hitter or outfielder. In his Opening Day start in Kansas City, LaMarque fired a five-hit gem against the Cleveland Buckeyes, going the distance and getting the win, 3-0.44 It was a solid pitching staff with LaMarque, George Walker, Cliff Johnson, Frank Barnes, and Mel Duncan. The first 11 games they pitched were all complete games.45 By early summer LaMarque also was leading the NAL with a .433 batting average.46

The Indianapolis Clowns won the Eastern Division and the Monarchs won the Western Division, but there were no playoffs between the division champs in 1950. LaMarque finished 6-7 with 53 strikeouts and a 3.25 ERA in 119 innings during his final season with Kansas City.47

As the integration of the White minor and major leagues, caused the Negro Leagues to diminish in stature and quality of play, another team became interested in LaMarque, and it had money and a strong team to create great appeal. The Fort Wayne Capehearts were preparing for another trip to Wichita for the semipro National Baseball Congress tournament. Lester Lockett was on the team but was unable to make the trip for the tournament. Most players were working full-time and sometimes could not get time off for the trip. Fort Wayne manager Red Braden always looked to add pitching around tournament time because teams played a lot of games in a short period of time. Braden added Pat Scantlebury but needed another durable starting lefty. The Monarchs had been to Fort Wayne a few times and Braden had seen LaMarque play, so he made him an offer to join the club. LaMarque was “wooed away from the Monarchs” and it “paid off handsomely” for Fort Wayne.48 On July 25 LaMarque made his Fort Wayne debut as a pinch-hitting left fielder. He then began to be used primarily as a pitcher. Prior to the tournament, LaMarque traveled back and forth between Fort Wayne and Kansas City and played for both the Capeharts and the Monarchs.

Fort Wayne headed to Wichita in late August to defend its national semipro championship. LaMarque’s first pitching assignment came in the team’s second game, on August 26, He pitched a complete game, scattering three hits against the Huntsville (Alabama) Boosters.49 His first loss came when he walked in the winning run after relieving Pat Scantlebury in the ninth inning. The Capeharts needed to win two more games in order to hold the national championship. Scantlebury got the ball in the first game, going 12 innings and winning 1-0. LaMarque got the ball for the deciding game and notched his third win in the tourney as he fanned 11 Elk City (Oklahoma) batters en route to a 5-2 championship win.50

The winners of the tournament were invited to play baseball in Japan and the Fort Wayne team headed for Tokyo for what was dubbed “the first inter-hemispheric series.”51 The Capeharts opened their tour of Japan with a win. LaMarque got the ball for game two against Kanebo and gave up eight hits in a 13-inning complete game that ended in a tough 1-0 loss in front of 30,000 at Osaka.52 At season’s end, LaMarque joined Scantlebury on the National Baseball Congress All-American team.53

LaMarque ventured to Mexico for the 1951 season. Joining a number of former Negro American Leaguers, he pitched for the Mexico City Red Devils, for whom he went 19-6 with a 4.17 ERA in 233⅓ innings pitched.54

There were reports that LaMarque was coming back to Fort Wayne for the 1952 season. However, the Vans, as the Fort Wayne team was now called, wondered about reports that he had signed with the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association.55 Monarchs owner Tom Baird told Vans skipper Red Braden that he had first claim on LaMarque but would waive the claim in favor of the Vans. A call was also made to Milwaukee to clear the air on the issue.56

The holdup could have been the Chihuahua Dorados in the Class-C Arizona-Texas League. LaMarque was listed as a pitcher for the team and was being counted on as its ace. By this time he was living in Fort Wayne and working for General Electric. He appeared in at least some games for the Vans.57 The following season, 1953, LaMarque looked to be the ace in Fort Wayne. He beat both the Clowns and Havana Cuban Giants in exhibition games in town, even pinch-hitting against his old team, the Monarchs, in one game. LaMarque returned to Fort Wayne in 1953 and continued to 1955 but the talent for the team was just not up to standard. The 1953 Vans did not qualify for the semipro tournament.

LaMarque was back in 1954 as Fort Wayne tried to get back to Wichita. LaMarque was primarily playing outfield as manager Braden liked his bat in the lineup. The Vans won the Indiana state title but were beaten in Wichita.

By 1955 Fort Wayne had lost a few of its better players. LaMarque went from playing outfield to some relief pitching but the team was just not as good as in years past.

The year 1956 brought renewed hope that Fort Wayne – now named the Allen Dairymen after a new sponsor – had assembled a team that could once more compete for the semipro world title. The schedule for the Fort Wayne team was to play all home games, and the Wichita tournament was the goal. LaMarque pitched regularly during the season but did not take the mound often during tournament time, though he did contribute at the plate and in the outfield. The team added three other former Negro League players: Jim Mason, speedster John Kennedy, and Wilmer Fields. The team finished the home schedule 18-1 and qualified for the Wichita tourney. The Dairymen won the playoffs there and went on to Milwaukee, winning the Semipro Global World Series, by a 2-0 score over Hawaii.58

In 1957 LaMarque and Fields played again for Fort Wayne. The Dairymen went to the NBC tournament finals but lost to Sinton, Oklahoma.59

By 1958 LaMarque was winding down his career. He left Fort Wayne about midseason and moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where he began assembly-line work for the Ford Motor Company in nearby Claycomo. “He was a final repairman on the assembly line at Ford Motor Company. He worked there 31 years, before retiring in 1997,” his wife, Antoinette, said in 2021.60

He and Antoinette had met in 1969. She recalled, “I had worked at a clothing company and managed a clothing store. I took a part-time job as a bartender because I had children of my own to take care of. The Ford Motor Company was on strike and he came in to have a drink. The bar was on the corner. In fact, we lived down the street from each other and we didn’t know each other. We did eventually marry. We married in ’74.61

LaMarque received sad news on June 13, 1982. Satchel Paige had died, and LaMarque was asked to be one of the 13 honorary pallbearers for the Hall of Fame hurler. As the outside world learned more about the Negro Leagues, LaMarque was invited to make several appearances at events in the Kansas City area, including one with former Monarchs, Blues, A’s, and Royals players. He was also invited to a number of baseball card shows and became something of a Negro League ambassador.

A few months after the death of Cool Papa Bell, LaMarque said in an interview, “When you watch Rickey Henderson, you are watching Cool Papa. He was good a baserunner as I’ve ever seen. Compared with Rickey, I would take Bell because I think Cool was quicker than him. And Cool Papa wouldn’t take a big lead when he was on base; he’d only be one to three feet off the bag when he tried to steal.”62

At the opening ceremony of the Satchel Paige School in Kansas City, LaMarque asserted, “I think it’s one of the greatest things that ever happened. I hope these children will learn and grow and remember the man their school was named after.” The school was closed in 2018.63

During the opening ceremonies for the Negro League Museum in Kansas City in July 1994, LaMarque said, “To me, it’s about the greatest thing that’s ever happened to me.”64 In an earlier interview he said, “It’s good for the younger generations: they need to know their history. Now it’s only fathers and grandfathers who remember us.65 In 1995 he was one of the Negro Leagues players pictured on a series of cellphone cards issued by the PhoneLynx company.

Asked in 1997 about playing with Jackie Robinson in 1945, LaMarque said, “Jackie Robinson was tough enough to take the abuse he’d get in the major leagues.” He added, “We helped him learn how to steal bases. But he learned other things too, and that’s what made him the right choice, in my opinion. He was really intelligent. We had guys who were better on the field, but he was a great person. And the first black player in the major leagues had to be flawless.” Having been able to play with Robinson still brought a smile to LaMarque’s face. “It was a special time, when I was playing with him, he was just another ballplayer to me, maybe to everyone else. But now you think of it as history, and we were there with him.”66

Antoinette LaMarque said Jim maintained contact with other Negro Leagues veterans:

“They enjoyed being together. They kept on with each other over the years. They were each there for the other ones. They were quite a group. A lot of people thought they made millions of dollars. But they didn’t. They made maybe $600 or $700 a month.

“He was involved quite a bit, even after he retired from baseball. He did a lot of community work. He especially loved children. He wasn’t too concerned about the adults. They were just out to get his autographs and put it on eBay so they could sell it. But he was always interested in the children. Whenever they would write and they would be doing Black history or whatever, and they would send him cards, he would always sign cards and send them back to them. He did that up until the day he died.”67

Major League Baseball’s recognition of the Negro Leagues to have been major leagues means LaMarque is now defined as a former major-league ballplayer. That probably feels good, it was suggested to her. “Yes, it does. It does. It’s quite exciting.”68

James Hardin LaMarque died on January 15, 2000, with his wife, Antoinette, and youngest daughter, Kimberly, by his side. He had two daughters from an earlier marriage (Joyce LaMarque Smith and Gloria Jean LaMarque Clay) and a son James Jr., who died in 1975. “He died from COPD, because of smoking,” Antoinette said. “I tried for years to get him to stop smoking, but he would hide cigarettes. It became a family joke. He would hide them around, in places. I would find them and throw them out. He’d just go get some more. That’s what he died from.”69 His headstone gives his birth year as 1921, though most documents show 1920.70 He was buried at Forest Hills Cemetery in Kansas City, Missouri.

After LaMarque’s death, Bob Kendrick, a Negro League Museum spokesman who is now the institution’s president, said, “He had some impressive numbers with the Kansas City Monarchs. He was part of an impressive pitching staff. He was one of the aces of the staff. He should have gotten a strong look by the majors.” Although LaMarque had been one of the premier lefties in the Negro Leagues during the 1940s, “He wasn’t like Satchel Paige or Josh Gibson with a household name. He was an example of the kind of player that just loved playing the game of baseball. And the Negro Leagues gave Lefty the opportunity to do just that.”71

Sources

Seamheads.com was used for most Negro League season statistics. Negro League statistics vary from source to source; thus, the author also used the website of the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, if a newspaper story corroborated the numbers supplied. These statistics were posted by the Howe News Bureau, which was the official statistician for the Negro Leagues.

Notes

1 Steve Penn, “Lefty’s Baseball Legend Lives On,” Kansas City Star, February 9, 2000: City 3.

2 Shelley Smith, “Remembering Their Game,” Sports Illustrated, July 6, 1992, https://vault.si.com/vault/1992/07/06/remembering-their-game.

3 Ancestry.com United States Federal Census 1930; United States WW II Draft cards young men 1940-47.

4 Laura Miserez, “Family Remembers Kansas City Monarchs’ All-Star Pitcher ‘Lefty’ LaMarque,” Missoulian.com, March 4, 2021. https://www.emissourian.com/features_people/family-remembers-kansas-city-monarchs-all-star-pitcher-lefty-lamarque/article_a4ada812-7c7f-11eb-b089-ffc6d1ab4464.html. Accessed March 5, 2021.

5 Brent P. Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited (Jefferson, North Carolina; McFarland, 1998), 164.

6 The Negro Leagues Revisited, 164.

7 “‘Satchel’ Paige and Kansas City Monarchs in Yankee Stadium’s Biggest Attraction Sunday August 2,” New York Age, August 1, 1942: 11.

8 “Johnson Bangs Long Wallop to Decide Contest,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, July 17, 1942: 13.

9 “Clowns in Midst of Long Playing Tour,” Jackson (Mississippi) Advocate, October 3, 1942: 6.

10 Miserez.

11 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 469.

12 It was a game in which the visiting Birmingham Black Barons had already run up a 20-0 lead by the time LaMarque homered; the final score was 20-6. LaMarque was not among the four Kansas City pitchers in this game. See “Monarchs in 20-6 Loss,” Kansas City Times, July 21, 1944: 13. Three days later, he was one of two pitchers victimized by the Buckeyes in a 16-9 loss at Ruppert. LaMarque played other positions as well, when needed, for instance as center fielder in a July 14, 1948, game in Benton Harbor, Michigan, against the local Buds. See “Buds Defeat Kansas City Monarchs, 7-6,” News-Palladium (Benton Harbor), July 15, 1948: 16. He played left field against the Atchison (Kansas) Colts on August 6. See “Colts Bow to Monarchs,” Atchison Daily Globe, August 7, 1948: 5.

13 Ric Roberts, “Paige on Mound in First Tilt,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 1, 1944: 12.

14 Jeffrey Flanagan, “A Stop in KC,” Kansas City Star, April 15, 1997: 8.

15 “LaMarque to Hurl Against Dexters for K.C. Monarchs,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 22, 1945: 13.

16 “14,000 Witness Paige Score 4 Hits at Yankee Stadium, Sun.,” New York Age, June 23, 1945: 11. The final score was 4-1, the Stars getting their one run on two walks and two infield outs.

17 “Monarchs to Play Barons,” Kansas City Star, July 8, 1945: 18.

18 “Monarchs Beat Barons,” Dayton Daily News, July 27, 1945: 21.

19 “A Homer Beats Monarchs,” Kansas City Times, August 8, 1945: 7.

20 “Monarchs to Play Here,” Kansas City Star, August 22, 1945: 14.

21 “Shut Out the Clowns,” Kansas City Times, September 19, 1945: 7.

22 “Beers to Face Monarchs Here,” South Bend Tribune, June 23, 1946: 32.

23 “Clowns Top Kansas City Twice, 10-3 and 2-0,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 27, 1946: 17.

24 “Memphis, Monarchs Split Two,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 31, 1946: 17.

25 Rich Puerzer, “September 17-29, 1946: Newark Eagles Get the Best of Kansas City Monarchs in Negro League World Series,” SABR Games Project,

26 LaMarque gave up the three runs and was the losing pitcher. See “Feller, Satchel in Scoreless Three Inning Mound Stints,” Council Bluffs Nonpareil, October 13, 1946: 17.

27 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 278, 281.

28 Kelley, 166.

29 “4 Monarchs Play Baseball All Year Long,” St Joseph Gazette, June 4, 1949: 9.

30 “Kansas City Trips Memphis, 8-2, 9-3,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 31, 1947: 14.

31 “9000 See Monarchs Beat Memphis, 6-0,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 29, 1947: 15.

32 https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1947&lgID=NAL.

33 As always, there are discrepancies in reporting statistics, typically due to a lack of definition between league and nonleague games. The August 8 Alabama Tribune of Montgomery, for instance, reported that LaMarque’s 9-2 record was at that point the best in the NAL. “Art Wilson Sets Pace in Negro American League,” Alabama Tribune, August 8, 1947: 6. The August 27 St, Louis Globe-Democrat reported him as 11-2.

34 Figueredo, 293-94.

35 Penn.

36 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 313.

37 Lester, 321.

38 It was Satchel Paige Day at Wrigley. “Satch Paige’s Day Success; Defeats Bearden Team, 4-2,” Los Angeles Mirror-News, October 25, 1948: 56.

39 Thomas Van Hyning, Santurce Crabbers: Sixty Seasons of Puerto Rican Winter League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1999). Mayaguez won the series.

40 LaMarque’s nickname in Puerto Rico was Libertad after the Argentine singer, Libertad Lamarque. Thomas Van Hyning, Santurce Crabbers, 30.

41 “Negro American League 1949 Statistics,” http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Stats/NAL%201949/NAL1949.pdf, accessed February 22, 2021.

42 Lester, 335-36.

43 C.E. McBride, “Sporting Comment,” Kansas City Star, April 14, 1949: 18.

44 Elston Howard, left fielder for the Monarchs, doubled and scored the first run of the game in the second inning. “Shut Out Bucs,” Kansas City Times, May 8, 1950: 15.

45 “Two Stars with Memphis,” Kansas City Times, June 1, 1950: 20.

46 “Black Barons Striving to Overtake Monarchs in Series; Clubs Play Here Tonight,” Montgomery Advertiser, July 3, 1950: 7.

47 “Negro American League 1950 Statistics,” http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Stats/NAL%201950/NAL1950.pdf, accessed February 22, 2021.

48 Ed Shuoe, “Now Hear This,” Emporia (Kansas) Gazette, September 5, 1950: 3.

49 Bill Hodge, “Fort Wayne Cashes In on Errors to Ease by Boosters, 4-3,” Huntsville Times, August 27, 1950: 12.

50 Associated Press, “TU Hurler Named ‘Most Popular’; Elk City Loses,” Tulsa World, September 7, 1950: 31. See also United Press, “Elks Lose but Break Ump’s Nose,” Clinton (Oklahoma) Daily News, September 7, 1950: 5.

51 “Win Fourth Straight Non-Pro Title,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1950: 13. A photograph of the team accompanied the article.

52 “Kanebo Club Beats Capes in 13thh, 1-0,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, September 14, 1950: 23. The September 14 issue of Pacific Stars and Stripes offers good coverage of this game. LaMarque was 3-for-5 at the plate in the 13-inning game, according to the September 17 Pacific Stars and Stripes.

53 International News Service, “Lafayette’s DeWitt on All-Star Nine,” Journal and Courier (Lafayette, Indiana), September 12, 1950: 20.

54 Pedro Treto Cisneros, The Mexican League Player Statistics 1937-2001 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011), 474.

55 The signing was reported in, among other publications, the Pittsburgh Courier. “Brewers Ink Lamarque,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 24, 1952: 15.

56 “Vans’ LaMarque Hasn’t Signed with Milwaukee,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, May 7, 1952: 18. Five days later, the Gazette said that LaMarque had been giving Vans officials “insomnia with his wanderings about the country.” See “LaMarque Due In Today,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, May 12, 1952.

57 See “Auscos Tip Sutherland in 3-1 Tilt,” News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), August 13, 1952: 18.

58 Bob Pinkowski, “US Beats Hawaii, 2-0, for Global Baseball Title,” Milwaukee Journal, September 14, 1956: 15. Pete Olsen threw a three-hitter for Fort Wayne.

59 “Texas Club Wins NBC,” Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, September 3, 1957: 30.

60 Interview with Antoinette LaMarque by Bill Nowlin on February 20, 2021.

61 LaMarque interview.

62 “Negro League Nostalgia; Memories as Great as Players,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), August 19, 1991: 8.

63 Tim O’Connor, “Players, Family Help Dedicate Paige School,” Kansas City Star, October 10, 1991: 31.

64 “Negro League Museum Makes Debut in Kansas City,” St Louis Post-Dispatch, July 17, 1994: 63.

65 David Conrads, “Rescuing the Rich History of Black Baseball,” Christian Science Monitor, February 8, 1991: 14.

66 Flanagan, 8, 9.

67 LaMarque interview.

68 LaMarque interview.

69 LaMarque interview.

70 Two such documents are his listing on the Social Security Death Index and his World War II draft registration card, which he completed himself, At the time, he was 21 and working for the Sanitary Barber Shop in Potosi.

71 Penn.

Full Name

James Hardin LaMarque

Born

July 29, 1920 at Potosi, MO (USA)

Died

January 15, 2000 at North Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.