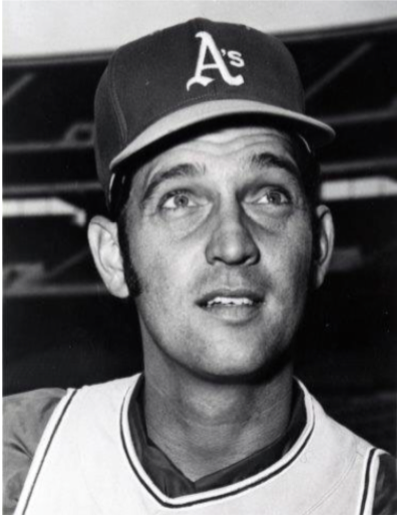

Jim Roland

Signed by the Minnesota Twins in 1961, left-hander Jim Roland debuted as a 19-year-old in a September call-up the following season and tossed a three-hit shutout in his first big-league start, in 1963. “[He] has a blazing fast ball and is effectively wild,” wrote Twins beat reporter Arno Goethel.1 Battling injuries and control issues throughout his ten-year big-league career, most notably with the Twins and Oakland A’s (1962-1972), Roland never realized the potential his inaugural start suggested and was relegated to the unglamorous role of long reliever and mop-up artist. He was also unlucky: Seven years after Roland missed the Twins’ pennant in 1965 when he spent the year in Triple-A, the A’s sold him to the New York Yankees in 1972, the season they won their first of three consecutive World Series.

Signed by the Minnesota Twins in 1961, left-hander Jim Roland debuted as a 19-year-old in a September call-up the following season and tossed a three-hit shutout in his first big-league start, in 1963. “[He] has a blazing fast ball and is effectively wild,” wrote Twins beat reporter Arno Goethel.1 Battling injuries and control issues throughout his ten-year big-league career, most notably with the Twins and Oakland A’s (1962-1972), Roland never realized the potential his inaugural start suggested and was relegated to the unglamorous role of long reliever and mop-up artist. He was also unlucky: Seven years after Roland missed the Twins’ pennant in 1965 when he spent the year in Triple-A, the A’s sold him to the New York Yankees in 1972, the season they won their first of three consecutive World Series.

James Ivan Roland, Jr. was born on December 14, 1942, in the small town of Franklin, nestled in the Smoky Mountains of western North Carolina. His parents were James Ivan Sr., a pipefitter by trade, and Florence Virginia (Henson) Roland. By the time Jim was in the fourth grade in the early 1950s, the family had relocated to Raleigh, more than 300 miles to the east, where Jim Sr. found employment as a guard and maintenance man at a local prison. Like many youths, Jim Jr. got his start on the diamond in a local Little League. By the time he was a junior at Broughton High School in Raleigh, the tall (6-feet-3), yet thin (160-pound, though he grew bigger) hard-throwing southpaw had the attention of scouts. On the recommendation of scout Al Evans, Minnesota Twins executive vice president Joe Haynes signed Roland upon his graduation in 1961 for a $50,000 signing bonus. It was widely reported that the hefty financial incentive was the largest the Twins/Senators ever paid to a pitcher.2 (The Washington Senators relocated to Minnesota for the 1961 season.)

Just weeks removed from high school, the 18-year-old Roland began his professional baseball career in the Class B Carolina League with the Wilson Tobs, a team located less than 50 miles from his hometown. Roland impressed the Twins brass by winning seven of 13 decisions and posting a fine 3.15 ERA in 123 innings for the first-place Tobs. After the season, he was added to the Twins’ 40-man roster and sent to the Florida Instructional League to work on his control (4.9 walks per nine innings) with manager Del Wilber, a former big-league catcher and respected developer of young pitching prospects.3

Roland, coming off an ankle operation in the offseason, reported to Minnesota’s spring-training facility in 1962. The Twins had finished with a lackluster 70-90 record (seventh place) in the first year of expansion in the AL, and desperately needed a hard-throwing lefty to compete with the likes of the New York Yankees and Detroit Tigers. With less than a full season of Class B ball under his belt, Roland was sent along with other prospects (outfielder Tony Oliva and another hard-throwing lefty, Gary Dotter) to the Class A Charlotte (North Carolina) Hornets of the South Atlantic League (Sally). Roland struggled against more experienced competition (1-3, 4.17 ERA in 41 innings) and was reassigned to Wilson. Roland excelled for the below-.500 club. Named to the league’s all-star team, he sported only a 10-8 record, but was the hardest-to-hit hurler in circuit (5.4 hits per nine innings), ranked second in ERA (1.98), and was third in strikeouts per nine innings (10.6). Twice the southpaw struck out 14 batters in a game to go along with 12 and 13 punchouts in two other contests,

Roland’s performance with the Tobs earned him a late-season look-see with the Twins. On September 20 he made his major-league debut (and his only major-league appearance of the season). In relief of Jim Kaat, Roland tossed two scoreless innings, yielding a hit and striking out one.

The young lefty was back with Del Wilber in the Florida Instructional League in the fall of 1962. For all of his potential, Roland also walked 6.1 hitters per nine innings for the Tobs. Along with teammates Oliva, Orlando Martínez (infield-utility), and Joe McCabe (pitcher), Roland was named to the league’s all-star team. He was also chosen as the “Rookie Pitcher” in the Florida Instructional League. He was widely expected to be the Twins’ fifth starter in 1963.4

Roland made a big splash in his second camp with the Twins. “[He’s] blossomed as the surprise of spring training,” praised The Sporting News.5 The newspaper also tabbed him as the “Best Young Pitcher” and the “Most Personable Newcomer” in light of his constant smile, talkative personality, and infectious enthusiasm.6 “Lots of good natural stuff,” said manager Sam Mele of his youthful prospect.7 Roland earned his first big-league win in a wacky game on April 16, 1963, at Metropolitan Stadium. The eighth Twins pitcher of the contest, he tossed the last two frames against the Los Angeles Angels. He gave up a go-ahead run in the 13th inning, but was bailed out by the powerful Twins offense in the bottom of the frame. Roland tossed a masterful three-hit, 144-pitch shutout in his first major-league start, on April 21 against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park. He whiffed seven, but also walked nine, and got out of bases-loaded jams in the first and fifth innings. After struggling in his next four starts, Roland hurled a complete-game five-hitter on June 1 to defeat the Detroit Tigers, and seemed even stronger in his next outing, on June 5, when he held the Kansas City A’s to just two hits in seven innings. However, that game proved to be disastrous for his career. “Something snapped,” said Roland about the pain he felt in elbow after a pitch in that game.8 “My elbow was swollen so much I couldn’t wear a suit coat because the sleeve wouldn’t fit over the elbow.”9 Save for a brief one-third-inning outing six weeks later, Roland was inactive for the rest of the season. Team physician Dr. Bill Profitt diagnosed the injury as ripping “scar tissue in his muscle,” but not a tear, and prescribed rest.10

Sportswriter Arno Goethel, described Roland as “one of the biggest question marks in the Twins camp” in 1964.11 The question mark got even bigger when Roland arrived in camp more than 40 pounds overweight – at about 223 pounds – drawing the ire of Mele.12 The Twins had two dependable left-handed starters, Jim Kaat and Dick Stigman; consequently, Roland was tabbed as a swingman. He had counted primarily on his overhand fastball, curve, and effective changeup through his first three years in the pro ball, but added a slider to his repertoire in spring training. He unveiled the pitch in a spot start against New York in Yankee Stadium on May 19. He hurled a career-high 12 innings (and faced 50 batters), holding the eventual pennant winners to seven hits and two runs, while striking out eight and walking six. He was replaced by pinch-hitter Lenny Green in the 13th inning when the Twins exploded for five runs, making Roland the winner. Roland’s 12-inning effort has been surpassed only twice in Minnesota Twins history (Camilo Pascual went 12⅔ innings against Cleveland in 1963 and Jim Merritt logged 13 innings against the Yankees in 1967.) “I’ve never seen a pitcher pick up [the slider] any faster,” said pitching coach Gordon Maltzberger about Roland’s outing.13 Two starts later the southpaw tossed an overpowering two-hitter against the Boston Red Sox, but struggled thereafter, losing four of his next five starts and his spot in the rotation. Confined to mop-up duty for the remainder of the season, Roland posted a 2-6 record and a 4.10 ERA in 94⅓ innings, while battling control problems (6.0 walks per nine innings).

Roland’s once promising career had been marred by injuries (ankle and elbow), and by 1965 he seemed washed up at age 22. Dabbled as trade bait in the offseason, Roland struggled in spring training in 1965 under new pitching coach Johnny Sain. A pulled thigh muscle set him in further back in competition with Dwight Siebler, Dave Boswell, and Jim Merritt for a spot on the staff. He was optioned to the Denver Bears of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, where a series of immature incidents made manager Cal Ermer question his commitment to the game. Roland injured his knee jumping in protest of a call by a first-base umpire in July. And he committed the cardinal sin of walking off the mound on several occasions while Ermer was on his way to remove him.14 In primarily a starting role, the left-hander won eight, lost six, and posted a 3.81 ERA in 156 innings. He was recalled by the Twins in September but did not pitch.

Called a “problem kid” by Twins beat reporter Max Nichols, Roland reported to the Twins’ spring training hoping for a new beginning.15 He had been “disillusioned and discouraged” by his year in Denver, but appeared stronger and healthier in 1966.16 “Roland is throwing the way he did in 1963 – hard and low,” said team owner and general manager Calvin Griffith optimistically.17 Roland also donned spectacles for the first time, claiming that poor depth perception had contributed to his erratic pitching. Despite the praise, Roland couldn’t crack the deep Twins staff, and was sent back to Denver to start the season. Splitting his time with the Bears and the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League, Roland endured a horrific campaign, winning just six times, leading all Triple-A hurlers with 19 losses, and finishing with an unsightly 4.80 ERA in 163 innings. A September call-up, Roland made his first big-league appearance in more than two years by tossing two scoreless innings of mop-up duty in his only outing with the Twins.

Out of player options, Roland stuck with the Twins in 1967 and 1968. During spring training in 1967, an Associated Press story described Roland as “one of the most disappointing investments Calvin Griffith ever made.”18 Relegated to the unceremonious role of mop-up man, he logged only 35⅔ innings spread over 25 relief appearances in 1967 and 61⅔ innings (in 28 games) in 1968. His final win in a Twins uniform was a complete-game five-hitter (one of his four starts in the 1968 season) against the Washington Senators on August 27.

During those two years, the Twins tried everything to help Roland rekindle the magic his first start suggested. He joined less experienced prospects in the Florida Instructional league in 1967 in order to work extensively with Twins pitching coach, Early Wynn. The little-used Roland had developed bad habits and poor mechanics. “He’s been bending his waist,” said the future Hall of Fame pitcher, who admitted that it might be too late to reform the lefty.19

Roland’s approach to life changed radically during his season with Aragua in the Venezuelan winter league in 1967-1968. He pitched well (5-3 with a 2.24 ERA, plus three more victories in the playoffs), but lying awake at night in his one-room accommodation made him take stock in his career and purpose in life. “Suddenly I felt that if I couldn’t have my family with me, I needed somebody else on my side. I became a believer,” he told Arno Goethel. “Since I’ve become more serious about Christianity, I’ve eased my mind.”20 For the remainder of his life, Roland was guided by his religious convictions.

The sale of Roland to the Oakland A’s on February 24, 1969, merited little press coverage. In parts of six big-league seasons he had posted a 10-9 record and logged just 244⅔ innings. Nonetheless, the A’s were willing to take a chance on the hard-throwing left-hander, especially since he was just 26. After 13 consecutive losing seasons in Kansas City (1955-1967), the A’s were a team on the rise. In their maiden season in Oakland (1968), they enjoyed their first winning campaign since 1952, when they were located in Philadelphia and still owned by Connie Mack. Led by a young pitching staff including Catfish Hunter, Chuck Dobson, Blue Moon Odom, Jim Nash, Lew Krausse, and Rollie Fingers, the A’s seemed poised for an even better season in 1969.

In his first year with Oakland, Roland enjoyed his best season in the big leagues. While right-hander Fingers and left-hander Paul Lindblad were the first two firemen out of the bullpen, Roland was assigned to long relief and often pitched in mop-up games. The A’s lost 27 times in his 36 relief appearances (the team’s overall record was 88-74), but Roland sparkled with a 2.82 ERA in 60⅔ innings out of the bullpen. With the pennant out of reach, manager John McNamara gave Roland a chance to start. The southpaw responded by winning a career-best three consecutive starts, beginning with a complete-game four-hitter against the California Angels in Anaheim on September 21. “This is the best year I’ve got control of both my slider and fastball every time I go out there,” he said.21 Roland will forever hold the distinction of pitching the final game against the Pilots in their brief, one-year tenure in Seattle. In the 162nd game of the season, Roland limited the Pilots to seven hits and matched his career high with nine strikeouts in a 3-1 victory in front of just 5,473 spectators in the final major-league game in Seattle’s Sick’s Stadium. An atrocious hitter, Roland also recorded his last hit in the big leagues (he went 6-for-84 with one RBI in his career). A’s beat reporter Ron Bergman described Roland’s showing as a starter as “impressive,” while team brass promised to take a closer look at him as a fifth starter the next season.22 He finished the season with a 5-1 record and career- and staff-low 2.19 ERA in 86⅓ innings.

Breaking into the A’s starting rotation was easier said than done. The trio of Hunter, Dobson, and Odom had started 102 games between them and logged 713⅔ innings in 1969. However, the team lacked a left-handed starter. In spring training Roland competed for a job with hard-throwing Al Downing, acquired in the offseason from the New York Yankees. But Roland had an awful camp, struggled with mechanics, and was back in long relief, save for two ineffective starts.23 Downing won the job, but was ineffective, and ultimately was sent to the Milwaukee Brewers at the trading deadline. Ron Bergman called Roland “one of the best (long relievers) in the business” and noted that the role is “one of the least respected jobs in baseball.”24 Roland hurled 2⅓ and 3⅔ innings to earn victories in August, but the latter win was costly. In that game, on August 11, he collided with the Cleveland Indians’ Ray Fosse at home plate and tore ligaments in his right knee. “It was like hitting a wall,” said Roland, who tried to jump over Fosse, instead of barreling over the catcher as Pete Rose had done about a month earlier in the All-Star game.25 Roland landed on the disabled list and pitched just twice after that, finishing with a robust 2.70 ERA in 43⅓ innings spread over 28 appearances. His injury opened the door for the highly-touted prospect lefty Vida Blue, who was summoned from Triple-A Iowa.

With the triumvirate of Fingers, Bob Locker, and rubber-armed lefty Darold Knowles firmly ensconced as the A’s relievers, Roland occupied his position at the far end of the bullpen bench in 1971. Manager Dick Williams called on him 31 times, and 26 of those were in mop-up losses. Roland went 1-3 with a 3.18 ERA in 45⅓ innings.

Plagued by recurring arm pain, Roland was a baseball nomad in 1972. After just two appearances for the A’s, he was sold to the New York Yankees on April 28. A little more than four months (and 16 mainly ineffective appearances) later, he was traded to the Texas Rangers for pitcher Casey Cox. A combined 5.28 ERA in 30⅔ innings earned Roland his outright release from the Rangers. At just 29 years of age, Roland’s professional career was over.

Roland chalked up a 19-17 record over parts of ten seasons, and compiled a 3.22 ERA in 450⅓ innings. In four seasons in the minor leagues, he went 32-42 with a 3.48 ERA in 651 innings.

After his playing days, Roland returned to North Carolina and began a long and successful career as a business representative for a sporting-goods company. He was active in the Elizabeth Baptist Church in his hometown of Shelby, North Carolina. Diagnosed with cancer, he retired from his job in January 2010. On March 6, 2010, Roland died in Shelby. He was survived by his wife, Vicki (Whiten) Roland, and four adult children, James III, Jan, Lori, and Megan.26 He was buried in Oakland Cemetery, in Gaffney, South Carolina, his wife’s hometown, about 20 miles from Shelby.

An updated version of this biography was published in “1972 Texas Rangers: The Team that Couldn’t Hit” (SABR, 2019), edited by Steve West and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Chicago Tribune

New York Times

The Sporting News

Ancestry.com

BaseballAlmanac.com

BaseballCube.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

SABR.org

Notes

1 The Sporting News, February 1, 1964, 22.

2 The Sporting News, May 4, 1963, 9.

3 The Sporting News, October 11, 1961, 26.

4 The Sporting News, April 13, 1963, 5.

5 The Sporting News, April 6, 1963, 2.

6 The Sporting News, April 20, 1963, 14.

7 The Sporting News, May 4, 1963, 9.

8 The Sporting News, February 1, 1964, 22.

9 Ibid.

10 The Sporting News, December 7, 1963, 22.

11 The Sporting News, February 1, 1964, 22.

12 The Sporting News, March 26, 1966, 12.

13 The Sporting News, June 4, 1964, 8.

14 The Sporting News, July 17, 1965, 50.

15 The Sporting News, March 26, 1966, 12.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Associated Press, “Jim Roland May Yet Repay Twins,” The Daily Republic (Mitchell, South Dakota), March 28, 1967, 9.

19 The Sporting News, October 28, 1967, 20.

20 The Sporting News, September 21, 1967, 9.

21 The Sporting News, September 27, 1969, 16.

22 The Sporting News, October 18, 1969, 36.

23 The Sporting News, April 18, 1970, 12.

24 The Sporting News, September 5, 1970, 10.

25 Ibid.

26 Obituary, Shelby (North Carolina) Star. legacy.com/obituaries/shelbystar/obituary.aspx?n=jim-roland&pid=140499740.

Full Name

James Ivan Roland

Born

December 14, 1942 at Franklin, NC (USA)

Died

March 6, 2010 at Shelby, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.