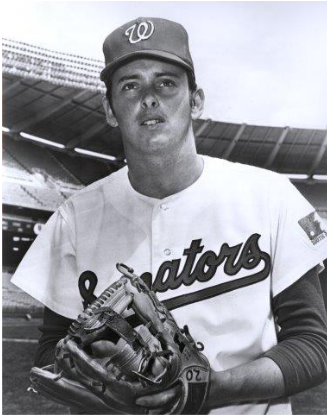

Joe Coleman (the Younger)

Three months removed from high school, hard-throwing right-hander Joe Coleman burst on the national scene by tossing a four-hit complete-game victory in his debut with the Washington Senators in 1965. Among the most durable pitchers of his day, Coleman averaged 15 wins and 252 innings over an eight-year span (1968-1975) for the Senators and Detroit Tigers. The two-time 20-game winner and one-time All-Star concluded his 15-year big-league career in 1979 as a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Three months removed from high school, hard-throwing right-hander Joe Coleman burst on the national scene by tossing a four-hit complete-game victory in his debut with the Washington Senators in 1965. Among the most durable pitchers of his day, Coleman averaged 15 wins and 252 innings over an eight-year span (1968-1975) for the Senators and Detroit Tigers. The two-time 20-game winner and one-time All-Star concluded his 15-year big-league career in 1979 as a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Joseph Howard Coleman was destined to become a baseball player when he was born in the Richardson House wing of Boston Lying-in Hospital on February 3, 1947. His father, Joe (Joseph Patrick) Coleman, was a big-league pitcher and one-time All-Star who went 52-76 in parts of 10 seasons spanning the years 1942-1955, mainly with the Philadelphia A’s, the Baltimore Orioles, and the Detroit Tigers. “I can remember a time that I sat on Mr. (Connie) Mack’s knee for a picture,” said Coleman about living a boy’s dream on the field in Shibe Park, shortly before the historic ballpark was renamed Connie Mack Stadium. “After the games I used to run around the infield and slide into every base.”1 The youngster accompanied his father and mother, Barbara, to spring training, and often traveled with the team to visiting ballparks. By the time he was 7 years old and with his father’s career winding down, young Joe knew that he wanted to become a baseball player.

The Colemans lived in Natick, a town of about 20,000 residents located 20 miles west of Boston. Joe got his first taste of organized baseball while attending Bennett-Hemenway Elementary and Wilson Junior High Schools. At Natick High School, the right-handed Joe developed into an overpowering, dominant pitcher, winning 24 of 28 decisions; he also played basketball. “My father never pushed me,” said Joe of his interest in baseball. “He let me pitch. If I had a question, then he’d help me.”2 But father Joe, who opened a sporting goods store in Natick, took obvious delight in his son’s success. “By his senior year,” said the elder Coleman, “[scouts] were swarming all over the place.”3 Joe had begun attracting attention while participating in Ted Williams’s baseball camp in Lakeville, Massachusetts, after his freshman through junior years, and had played in the Hearst Sandlot Classic game at Yankee Stadium in New York in 1964. As a senior in 1965, the 6-foot-3, 165-pound Coleman was considered one of the top pitchers in the country.

The Washington Senators, acting on the recommendations of team scouts Joe W. Lewis Sr. and Hal Keller, selected Coleman in the first round in the inaugural major league draft on June 8, 1965.4 He was the third overall pick (following outfielder Rick Monday by the Kansas City Athletics and pitcher Les Rohr by the New York Mets) and the first draft choice to make it to the major leagues. Coleman signed what Washington sportswriter Bob Addie called the “biggest bonus in Washington history,” a reported $75,000, with Senators general manager George Selkirk.5

Just weeks after graduating from high school, Coleman reported to the Class A Burlington (North Carolina) Senators in the west division of the Carolina League. He struggled against competition that averaged four years older, winning just twice in 12 decisions and posting a 4.56 ERA in 75 innings for a last-place team. The Washington Senators, plodding through their fifth consecutive dismal season since entering the American League as an expansion team in 1961 and drawing less than 7,000 per game, made national headlines when they called up the 18-year-old Coleman in late September.

Coleman made an auspicious big-league debut on September 28 in D.C. Stadium by tossing a complete-game four-hitter, striking out three and pitching around four walks to defeat another highly touted teenager, 19-year-old Jim “Catfish” Hunter of the Kansas City Athletics in the first game of a twilight-night doubleheader, 6-1. Coleman yielded back-to-back doubles with two outs in the ninth inning to lose his shutout bid. Five days later, he went the distance again, holding the Detroit Tigers to just five hits in a 3-2 victory in the nation’s capital. He got additional work with the Senators coaching staff in the Florida Instructional League in the fall.

Coleman arrived at the Senators’ spring training facility in Pompano Beach, Florida, in 1966 under the glare of media attention. His first camp, however, was a lesson in humility as he struggled and was assigned to the York (Pennsylvania) White Roses in the Double-A Eastern League. “I wasn’t in shape [and] I came down a week late because we had a little contract dispute,” said Coleman. “I was overweight, lazy, and had the wrong attitude.”6 On another last-place team, Coleman posted just seven wins, led the league in losses (19) and home runs allowed (17), and carved out a disappointing 3.75 ERA in 199 innings. Recalled by the Senators in September, Coleman made the most of his one start by tossing another complete game, a six-hitter to defeat his hometown Boston Red Sox, 3-2, in front of fewer than 500 spectators in D.C. Stadium on September 26 during the second game of a Monday afternoon doubleheader.

Regardless of Coleman’s 9-29 record in the minors so far, the Senators saw him as their future ace. “I think better up here than in the minors. The extra pressure makes me think more,” said Coleman, who landed a spot in starting rotation to begin the 1967 season.7 In his debut, he tossed 137 pitches and came within one out of his fourth consecutive complete game, but settled for his fourth straight win, beating a still-struggling New York Yankees team, 10-4. Another complete-game victory over the Chicago White Sox followed before reality set in. Coleman lost six of his next eight decisions and his 3.06 ERA ballooned to 5.33. Disconcerting to manager Gil Hodges, known as a disciplinarian, was Coleman’s spoiled-brat behavior, such as arguing balls and strikes with umpires and complaining when he was removed for a pinch-hitter. Despite winning four straight starts from July 13 through July 26, Coleman, struggling with an 8-9 record, was unexpectedly sent down to Double-A York in mid-August. “Coleman’s demotion surprised everyone,” wrote Bob Addie.8 Although Hodges claimed publicly that he thought Coleman was losing his confidence, he intended the demotion to be a wake-up call for his young hurler. Coleman was mainly relegated to the far end of the bullpen following his recall on Labor Day after a very rough starting assignment lasting just one-third of an inning on September 11 and finishing a once promising season with a disappointing 4.63 ERA (second highest among AL pitchers with at least 100 innings).

But Coleman emerged as a solid starter in 1968, leading the Senators, now managed by Jim Lemon, in starts (33), innings (233), and complete games (12), and lowering his ERA more than a run to 3.27. He credited his success to the Washington coaching staff. “There are better teachers in the big leagues. … Guys like [pitching coach] Sid Hudson who has taught me how to pace myself.”9 Coleman also mastered the forkball, which he had been playing around with for several years. “I started throwing it consistently in 1968,” he explained. “I saw some diagrams of how [Elroy Face] threw his forkball in Sport Magazine. But my father wouldn’t let me throw any kind of breaking stuff when I was a kid.”10 Coleman won 12 games, but also lost a team-high 16 for the last-place club. “If I’d go out and lose a close ballgame,” said Coleman, “I’d get upset and maybe throw my chair around the clubhouse. And the guys would get on to me.”11 Some teammates referred to him scornfully as “Boy Blunder” for his rookie-like mistakes and sore-loser sulking after poor outings.

At the baseball winter meetings in December 1968, Bob Short, treasurer of the Democratic National Committee and former owner of the Minneapolis Lakers of the National Basketball Association, purchased a controlling interest in the Senators. The following month he shocked the baseball world by luring Ted Williams out of retirement to pilot the club. Washington had not seen as much excitement and anticipation for Opening Day since the days of Walter Johnson. Described by Dick Couch of the AP as the “brightest young star” on the staff, Coleman tossed a complete-game victory in his season debut, but otherwise struggled through July 4, winning just four of 11 decisions and surrendering 19 gopher balls in 115 2/3 innings.12 Tabbed a disappointment by his manager, Coleman turned his season around by tossing three consecutive shutouts, surrendering just 11 hits while striking out 31, as part of a career-best streak of 32 1/3 consecutive scoreless innings. The 22-year-old cut down on his home runs-allowed total and established himself as the ace of the staff, leading the club in starts (36), innings (247 2/3), complete games (12), and shutouts (4), while finishing with a 12-13 record. “It was a matter of getting adjusted,” replied Coleman when asked about his dramatic midseason transformation. “I was on my own more, called my own game, did more things on my own after Ted knew me.”13 Coleman’s forkball, which batterymate Jim French called “the best in the league,”14 kept hitters off balance and helped him strike out 182 (tied for fifth most in the AL); “I need to throw three-quarter. Then my ball stays down and does something,” said a reflective Coleman, who also sported a robust 3.27 ERA.15 The surprising club won 86 games, the most for a major-league baseball team in Washington, D.C., since the 1945 Senators won 87, and finished in fourth place in the AL East in the first year of division play.

Coleman began the 1970 season seemingly prepared to continue his second-half surge from 1969. A four-game winning streak improved his record to 5-3 and lowered his ERA to 3.05 on June 10. One of those wins (a complete-game, 3-1 five-hitter over the Cleveland Indians) occurred on May 19 with umpire Ed Runge at first base; coincidentally, he was also the first-base ump when Coleman’s father (then with Baltimore) tossed a complete game to defeat the Washington Senators, 5-3, on that same date 16 years earlier. Coleman’s season unexpectedly veered out of control following losses in five consecutive starts and he was ultimately banished to the bullpen in early July. “Coleman is not the pitcher we thought he would be,” opined owner Bob Short.16 He returned to the rotation on August 2 for the second game of a doubleheader with rumors of his imminent trade in the offseason. While the weak-hitting Senators fell to last place in the AL East, Coleman dropped to 8-12 with a 3.58 ERA and exceeded 200 innings pitched for the third consecutive season.

Coleman and Williams had a contentious relationship, to say the least. Williams’s distrust (some would say dislike) of pitchers was well known from his playing days and things were no different during his tenure as skipper of the Senators. “What would you think of a guy who welcomed you to his camp by asking, ‘What’s dumber than a pitcher?’ and answered his own question by saying “Two,” said Coleman.17 Williams’s general lack of confidence in pitchers, his belief that they needed to last just five or six innings, and insistence that they throw sliders (a pitch that he had trouble with as a batter) further inflamed his relationship with Coleman. Miffed by “Teddy Ballgame’s” constant public berating of Coleman, Washington beat reporter Merrell Whittlesey noted that “Williams has been gruff at times with the youngster who should be the Senators star pitcher.”18 Coleman steadfastly refused to throw a slider and began to tune out his manager. “I knew that if I threw the slider, I’d risk hurting my arm,” Coleman told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor. “No matter how I tried, I couldn’t change Ted’s mind. He didn’t like my stubborn attitude.”19

Just days after the 1970 regular season ended, Coleman, dependable starting shortstop Ed Brinkman, swingman hurler Jim Hannan, and third baseman Aurelio Rodríguez were shipped to the Detroit Tigers for troubled former 31-game winner Denny McLain (who had been recently reinstated by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and pronounced “not mentally ill”20), utilityman Elliott Maddox, relief pitcher Norm McRae, and third-sacker Don Wert on October 9. The transaction is now considered among the most lopsided in baseball history, though at the time many thought McLain would return to the form that earned him two Cy Young Awards. The trade crippled the Senators franchise just prior to their last season in Washington and subsequent relocation to Texas). McLain went 10-22 in 1971 and was out of the big leagues a year later; McRae never appeared again in the majors; Wert played in only 20 games before being released before midseason; and Maddox had three mediocre seasons. Detroit sportswriter Watson Spoelstra excitedly called the trade the “steal of the year” for the Tigers who solidified three positions.21 Coleman developed into one of the most dependable workhorses in the league; the durable Brinkman shored up the middle infield for four years; and Rodríguez held down the hot corner for the remainder of the decade. Both infielders won Gold Gloves.

Coleman, who married Deborah Fitch just days after his trade, was in need of a change of scenery. The incessant losing and constant bickering with Williams had eroded his confidence. He looked forward to playing for a club that “makes money and puts people in the stands.”22 He also anxiously anticipated pitching for new Tigers manager Billy Martin, whose successful yet controversial one season as big-league skipper, guiding the Minnesota Twins to the AL West crown in 1969 was well documented.

In spring training with the Tigers, Coleman got the scare of a lifetime when he was hit in the head by a line drive off the bat of the St. Louis Cardinals’ Ted Simmons on March 27. “I never saw the ball coming,” said Coleman. “I don’t remember a thing until I was on the ground with people standing around me.”23 Rushed to the hospital, he was diagnosed with a nondepressed linear fracture in his skull. He was hospitalized for two weeks and placed on the 21-day disabled list, but made a miraculous and quick recovery. He debuted for Tigers on April 24, allowing two runs on five hits over five innings in a no-decision against the Oakland A’s. “You don’t how happy I am to be here,” said a relieved Coleman.24 Suffering from headaches and working his way into shape, Coleman found his groove beginning July 9 when he tossed 10 scoreless frames against the Senators during an 11-inning pitching duel with Pete Broberg and Casey Cox at RFK Stadium, winning 1-0 to start a personal six-game winning streak. He emerged as one of the hottest pitchers in baseball, going 13-3 over his final 20 starts, a majority of them on three days’ rest. “Pitching under Billy Martin has made all the difference in the world,” said Coleman. “He gave me a free rein with my pitches. He said ‘You’re a pro. You know what’s best for you. You pitch that way.’”25 That not-so-subtle dig at Ted Williams aside, Coleman exacted revenge again on his former club by whiffing a career-high 14 in a complete-game victory on September 15. For the second-place Tigers, Coleman finished with a 20-9 record and sported a 3.15 ERA in a career-high 286 innings while a teammate, southpaw Mickey Lolich, led the majors with 25 wins and 376 innings. Coleman also set career highs in strikeouts (236) and complete games (16).

Coleman won 62 games in his first three seasons with the Tigers (just one fewer than AL stalwarts Catfish Hunter, Jim Palmer, and Lolich, but well behind Wilbur Wood’s 70); however, his name rarely cropped up in discussions about the best pitchers in the league and he was once described as baseball’s “forgotten man.”26 Overshadowed by Lolich, Coleman was more relaxed with the Tigers, responded to the trust Martin had in him, and shed his “hot-head” temperament. “I regret that show of temper,” said Coleman of his days with the Senators. “It was a reputation I built up and it was a reputation I didn’t want. But at the time, I deserved it.”27 Being on a winning club with stars like Al Kaline, Bill Freehan and Norm Cash, who garnered most of the media attention, also helped. “I got more runs, better defense, and a better team effort behind me,” said Coleman. “When you’re playing for a loser, you play for yourself, because you know you’re not going to win.”28

Coleman’s development into a complete pitcher fueled his success. He claimed that he mellowed and no longer just tried to “blow the ball by the hitter.”29 Coleman possessed a strong fastball and increasingly relied on his elusive side-arm sinker and side-arm curve, but his forkball was his “out” pitch. “I don’t know where it’s going,” he said. “I just throw the ball down the middle of the plate and wait to see where it breaks.”30

Detroit captured the AL East crown on the next-to-last day of the 1972 strike-shortened season after a grueling, hotly contested division race with the Boston Red Sox, Baltimore Orioles, and New York Yankees. The now portly Coleman was at his best over the last six weeks of the season when the club needed him the most. He went 7-3 in his final 11 starts, including a masterful, four-hit, 11-inning shutout of the Minnesota Twins in the second game of a doubleheader on August 27. He finished the season with 19 wins, a career-best 2.80 ERA, and 222 strikeouts in 280 innings. He was a hard-luck loser; the Tigers scored just 14 runs in his 14 losses. Coleman was named to his first and only All-Star team, but did not pitch.

In the only postseason appearance of his career, Coleman tossed a gem in Game Three of the ALCS. He blanked the Oakland A’s on seven hits and struck out a then Championship Series-record 14 in the Tigers’ 3-0 victory. However, the Tigers eventually lost the best-of-five series, three games to two.

Coleman emerged as the club’s most consistent winner in 1973, collecting 15 victories by the All-Star break. However, Oakland’s Dick Williams, manager of the AL All-Star squad, snubbed the hurler, drawing Martin’s ire. The Tigers took over first place in early August before falling out of contention by losing 10 of 14 games. The team reached its nadir in now infamous episode on August 30 against the Cleveland Indians. Martin, incensed that the umpires had refused to take measures against Gaylord Perry and his alleged spitballs, ordered Coleman (in the midst of a seven-game losing streak) to throw the illegal pitch. Martin was suspended, and subsequently fired on September 2 in a move that shocked the team. Propelled by a five-game winning streak after the brouhaha, Coleman finished the season with a career-high 23 wins (15 losses), a 3.53 ERA, and 202 punchouts in 288 1/3 innings.

Coleman logged in excess of 200 innings for last-place Tigers teams in 1974 and 1975, but his record fell to 14-12 and 10-18 and his ERA rose dramatically to 4.32 and 5.55 (easily the highest in baseball). The Tigers were miffed by Coleman’s rapid decline and control problems (he issued a career-high 158 walks in 1974). I’ve never seen a pitcher at his age (27-28), who never has had any arm problems, have as much trouble as Joe has had for us the last two years,” said manager Ralph Houk.31 Coleman, who revealed that he had a painful “huge knot” in his shoulder in 1974, was equally frustrated. “At times, I didn’t have any idea what I was doing out there,” he said. “I was having an awful lot of trouble with my forkball … and it was always my out pitch.”32

Coleman spent his last four years (1976-1979) in the major leagues with six different clubs. After 12 mostly ineffective starts for Detroit in 1976, he was sold to the Chicago Cubs in an early June waiver transaction. No longer possessing his heater, Coleman moved to the bullpen and appeared in a career-high 51 games between the two clubs. He was traded to the Oakland A’s in spring training the following year for pitcher Jim Todd and enjoyed a rebirth of sorts (2.96 ERA in 127 2/3 innings) as a reliever and occasional starter. Following stints with the A’s, Toronto Blue Jays, and San Francisco Giants, the Pittsburgh Pirates signed him as a free agent on May 8, 1979, and assigned to their Triple-A affiliate in the Pacific Coast League, the Portland Beavers.

The Pirates called up Coleman after the All-Star break to shore up an already overworked bullpen facing a heavy schedule, including seven doubleheaders in three weeks. With the bullpen already overworked, Coleman took one for the team against the Cubs on August 7, tossing the final 5 1/3 innings and yielding nine runs in a 15-2 laugher, in a game which Dave Parker called the “incident.”33 “Our bullpen was beat up, and Joe knew that,” said Kent Tekulve. “Every inning, [Coleman is] getting more and more exhausted. He’s throwing a ton of pitches, and it’s hotter than heck. He’s sweating buckets. He’s got a towel over his head in the dugout. It got to the point where you were literally worried about him.”34 According to Pittsburgh sportswriter Joe Starkey, when an exhausted Coleman entered the dugout after the eighth inning, skipper Chuck Tanner said, “You just won the pennant for us!”35 Coleman pitched otherwise reasonably well and remained on the roster for the rest of the regular season, but was dropped for the postseason. Players voted him a half-share of their World Series winnings.

Coleman, just 32 years old, drew his release from Pittsburgh in the offseason, bringing his 15-year major-league career to an end. His final tally showed 142 wins, 135 losses, and a 3.70 ERA in 2,569 1/3 innings. He started in 340 of his 484 appearances, completing 94, and tossed 18 shutouts. Coleman was especially tough on All-Stars Jim Fregosi (5-for 46, .109), Thurman Munson (9-for-56, .161), and Robin Yount (5-for 31, .161), but encountered problems with light-hitting Ted Kubiak (10-for-25, .400), Jake Gibbs (11-for-28, .393), and Ed Herrmann (15-for-41, .366). Well respected by his teammates, Coleman also served as player representative for several teams.

After his release from the Pirates, Coleman began a long and successful coaching career. In 1980 he was named player-coach for the Spokane Indians, the Seattle Mariners’ and later California Angels’ Triple-A affiliate in the PCL, and held the position for three years; he also made at least 10 appearances per year for the team. A highly respected teacher and mentor for young hurlers, Coleman served as bullpen and pitching coach for the California/Anaheim Angels (1987-1990; 1996-1999), as well as roving pitching instructor (1995-1996). He was also the pitching coach for manager Joe Torre with the St. Louis Cardinals (1991-1994). Since 2000, Coleman was the pitching coach for several minor-league teams: the Triple-A Durham (North Carolina) Bulls (2000-2006) in the International League, and two clubs in the Class-A+ (Advanced) Florida State League, the Lakeland Flying Tigers (2007-2011) and the Jupiter Hammerheads (2012-2014).

A baseball lifer, Coleman grew up in big-league parks and spent more than a half-century in them as a player or coach. In 2010 he became part of the first family with three generations of big-league pitchers when his son, Casey, debuted with the Chicago Cubs. Coleman and his wife lived in Florida during the baseball season and in Tennessee in the offseason.

He died at the age of 78 on July 9, 2025, in Jamestown, Tennessee.

Sources besides those cited in Notes:

Joe Coleman player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York.

Ancestry.com.

BaseballLibrary.com.

Baseball-Reference.com.

Retrosheet.com.

SABR.org.

Notes

1 News Enterprise Association, “Jr’s Career Began in Dugout on Mr. Mack’s Knee,” The News (Frederick, Maryland), August 24, 1964: 21.

2 The Sporting News, September 18, 1965: 39.

3 Jack Sheehan, “Ball Park Always 2nd Home To Nats’ Coleman,” June 1967: 4. (Player’s Hall of Fame file, National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York).

4 Joe Coleman provided the names of these two scouts in his SABR Scouts Committee questionnaire.

5 The Sporting News, July 10, 1965: 22.

6 Murray Chass (Associated Press), “Pitcher Averages Better In Major Than In Minor Leagues. How Come?” The Daily Mail (Hagerstown, Maryland), April 4, 1967: 12.

7 Chass.

8 The Sporting News, September 2, 1967: 6.

9 Joe Sargis (Associated Press), “Coleman Learning How To Pace Self,” Ogden (Utah) Standard-Examiner, April 23, 1968: 10 A.

10 Frank Barrett Jr., “Young Coleman had it when Red Sox did not,” Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, August 7, 1971: 5.

11 The Sporting News, June 3, 1973: 3.

12 Dick Couch (Associated Press), “Joe Coleman Demonstrates Effects of Ted’s Theories,” Free Lance-Star (Fredericksburg, Virginia), March 25, 1969: 10.

13 The Sporting News, February 7, 1970: 43.

14 The Sporting News, August 2, 1969: 8.

15 Lew Ferguson (Associated Press), “Joe Coleman Still Needs Curve Work, Says Ted Williams,” Free Lance-Star (Fredericksburg, Virginia), June 5, 1969: 10.

16 The Sporting News, August 8, 1970: 28.

17 Morris Siegel, “Coleman hasn’t forgotten his two seasons with Ted,” Washington Times, March 17, 1992: D5.

18 The Sporting News, June 27, 1970: 22.

19 Ed Rumill, “Discards slider, Coleman gets free rein with Tigers,” Christian Science Monitor, May 28, 1971.

20 Ira Miller (UPI), “Denny McLain Sent To Senators In Eight-Player Transaction,” Cumberland (Maryland) News, October 10, 1970: 15.

21 The Sporting News, October 24, 1970: 11.

22 The Sporting News, February 6, 1971: 36.

23 The Sporting News, April 10, 1971: 26.

24 The Sporting News, May 15, 1971.

25 Rumill.

26 Fred McMane (UPI), “Joe Coleman Just Misses First No-Hitter,” Dubois County (Jasper, Indiana) Daily Herald, April 12, 1974: 12.

27 The Sporting News, June 16, 1973: 3.

28 Larry Paladino, “Line Drive To Head Didn’t Halt Joe Coleman,” Lakeland (Florida) Ledger, March 28, 1972: 1B.

29 UPI, “Joe Coleman Mellows With Age,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, May 19, 1973: C1.

30 The Sporting News, August 7, 1971.

31 The Sporting News, June 26, 1976: 16.

32 The Sporting News, May 24, 1975: 11.

33 Joe Starkey, “The 1979 Pirates: Where are they now?”, Tribune-Review (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), August 16, 2009, http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/sports/.

34 Starkey.

35 Starkey.

Full Name

Joseph Howard Coleman

Born

February 3, 1947 at Boston, MA (USA)

Died

July 9, 2025 at Jamestown, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.