Jorge Pasquel

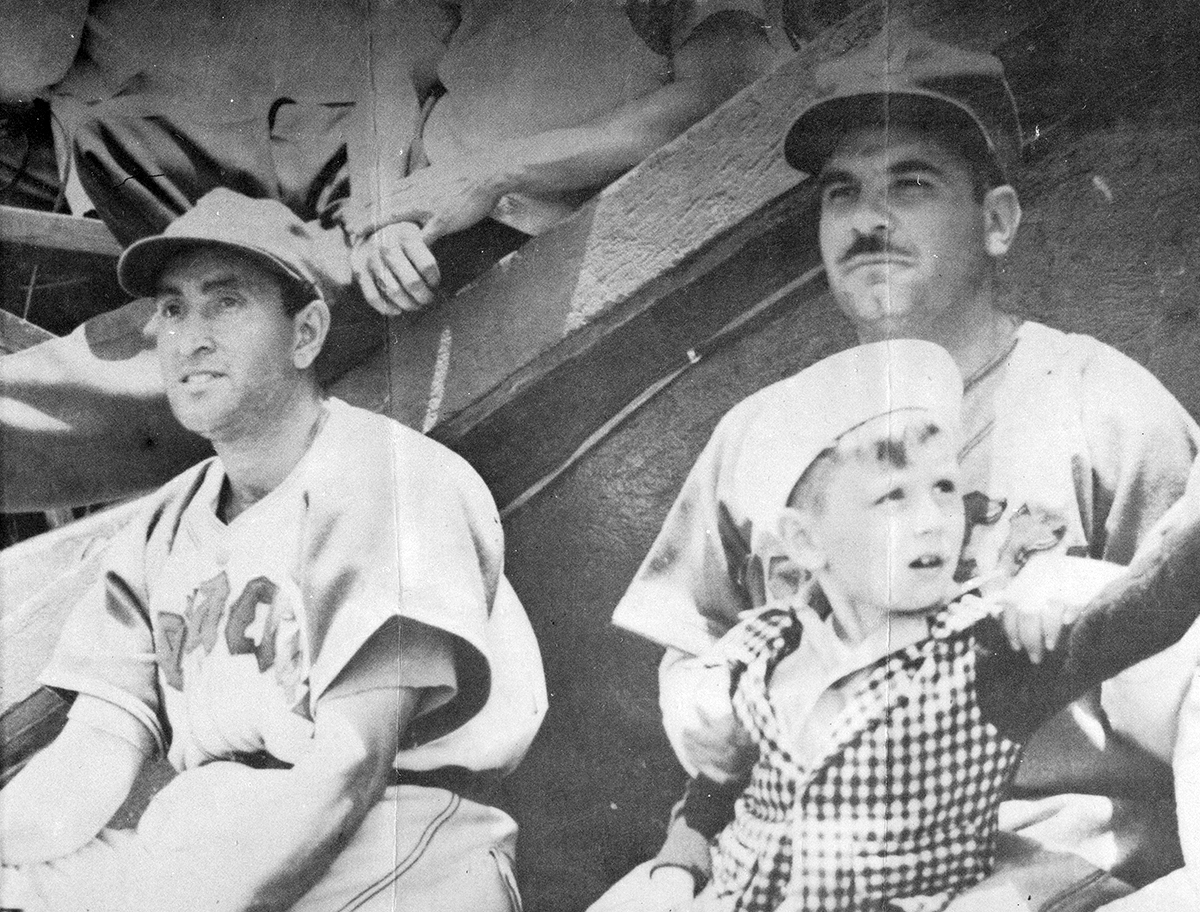

Mexican League president Jorge Pasquel, right, sits with the son of catcher Mickey Owen on his lap and outfielder Danny Gardella, left, during a 1946 game in Veracruz, Mexico. (SABR/The Rucker Archive)

Cardinals owner Sam Breadon called him likeable and said he was “the most dynamic fellow I’ve ever met.”1 Branch Rickey said he was like an adolescent with money and “an assassin of baseball careers.”2 Monte Irvin called him movie-star handsome and said he was “the George Steinbrenner of Mexico.”3 A Chicago Tribune article said he was so wealthy, he weighed his money, rather than counting it.4

And Life magazine said, “Most U.S. fans visualize Jorge Pasquel, president and virtual dictator of the eight-team Mexican Baseball League, as a sinister, swarthy and unscrupulous man of limitless means.”5

At the time the Life article was written, in 1946, Pasquel, who ruled an empire seemingly touching every aspect of the Mexican economy, was trying to upend Major League Baseball with his own Mexican League, poaching the United States for Negro League players, umpires, and ultimately major-leaguers. Although the Mexican League never became a serious competitor, it frightened the majors enough to cause changes that made the game more accommodating to players – and led to a lawsuit that was a stop on the way to free agency.

“Major league players should erect a shrine to Jorge Pasquel,” wrote legendary Newark Star-Ledger columnist Jerry Izenberg. “Pasquel had a tremendous impact on baseball.”6

***

Jorge Pasquel Casanueva was born on April 23, 1907, in Veracruz, Mexico, to Francisco Pasquel Landero and Marta Casanueva Balsa. He was the second of 11 children, eight of whom lived to adulthood. Marta was descended from a prominent Mexican cigar-making family. (Among the devotees to Balsa Brothers’ products was Winston Churchill.) The year after Pasquel’s birth, his father started an import-export company, Francisco Pasquel y Compañía, probably with seed money from his wife’s family. Veracruz was an important port on the Gulf of Mexico, and the Pasquel family business thrived.

While a boy, young Jorge made friends with another Veracruz boy from a prominent family: Miguel Alemán, whose father was a general in the Mexican Revolution.7 Alemán would go on to be Governor of Veracruz and later President of Mexico – a relationship from which Pasquel would reap benefits.

As a boy, Pasquel saw firsthand the conflict between the United States and Mexico. At the age of seven, he and his family hid in the basement of their customs house (the upper floor of which also served as their home) while American naval gunships shelled the city as the Woodrow Wilson administration intervened in the Mexican Revolution.8 A generation later, American press coverage of Pasquel’s raids of major-league talent would compare him to Pancho Villa.

Pasquel played a variety of sports in his youth – including baseball. He showed his intelligence at an early age, although he was expelled from the Unión Centro school for fighting. Pasquel maintained an interest in physical fitness throughout his life, neither smoking nor drinking, and engaging in regular exercise. He also cultivated a reputation for toughness, in fact killing a man in 1943 in a duel.9 Monte Irvin once told of visiting Pasquel at home and seeing enormous dogs, and machine guns on his desk.10

Although he came from a prominent family and was not obligated to do so, Pasquel, ever in search of a fight, joined the army at 22. His father had to intercede, getting him out of the service. He then took his place in the family customs house, and by 1930 was running it. Soon, the Pasquel family’s interests included everything from cars (they were the country’s agents for General Motors) to oil drilling, shipping, and real estate. When his father died in 1937, Pasquel became the patriarch not just of the business, but of his family – a rare feat, given that he was not the oldest son.11

Pasquel married Ernestina Calles on July 25, 1932. The bride was an even more prominent citizen than her groom. She was the daughter of former Mexican president Plutarco Elías Calles. The marriage lasted for a decade and produced no children before ending in divorce, which the Chicago Tribune described as “a circumstance which did not handicap him while pyramiding a $400,000 Vera Crus [sic] cigar business inheritance into an octopod financial empire embracing banks, ranches and custom houses.”12 Afterward, Pasquel, a handsome, trim, well-groomed man, was often seen in public with famous and attractive women in his native Mexico.13 Pasquel later remarried and was the father of two sons: Jorge and Miguel.14

As Pasquel rose to prominence in Mexico, so too did the game of baseball. The game was first played there in 1889, and the nation was a haven for amateur and barnstorming teams. Baseball became an important part of American foreign policy, promoted by the Warren Harding administration.15 In 1925, the Mexican League was founded, with teams in half a dozen cities, including Pasquel’s hometown of Veracruz. But the 1939 season ended with the Veracruz team, El Águila, forfeiting the final three games. Team directors were suspended, and it was unclear if Veracruz would field a team in the 1940 season. Pasquel stepped in and formed his own team, the Azules – which effectively rent the Mexican League asunder.

The quarreling soon led to two separate leagues, each with six teams. With double the teams, there was need for more talent, and Pasquel wasn’t shy about signing Negro League players. The Azules – which acquired the nickname Águila Negra (the black team) – had no fewer than six future Hall of Famers: Martín Dihigo, Willie Wells, Josh Gibson, Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, and Cool Papa Bell.16 Of course, they won the pennant.

Negro Leaguers were ecstatic to come play for Pasquel. Not only did he pay well – he boasted that his companies never had labor problems because he kept his employees happy – they found they were treated well, a marked change from the United States, where Jim Crow was the law in much of the land. Bill Cash, who played for the Mexico City team, said it was a thrill to see a water fountain without a sign that said, “whites only” – or “colored only,” for that matter. “The fans loved us there and treated us like kings,” he said. Double Duty Radcliffe’s niece recalled him saying that he experienced no prejudice while playing in the Mexican League.17

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese Navy Air Service attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, drawing the United States into World War II. Pasquel was briefly prohibited from traveling to the United States owing to his association with German industry, but all was forgiven as Mexico became a key ally for the United States (intercession from his friend Alemán – who had already issued him a diplomatic passport – probably didn’t hurt).

Pasquel even helped the war effort – in service of his own sporting interests. With a shortage of agricultural workers, Mexico loaned 80,000 farmworkers to the United States. All they wanted in return was two men: catcher Quincy Trouppe and pitcher Theolic Smith, both of whom would play baseball in Mexico. “George [sic] Pasquel was a powerful man,” Trouppe said. “It staggers my mind how he was able to bring about this astounding exchange.”18

While the war went on, many minor leagues suspended operations, unable to find players because of the war. Pasquel saw this as an opportunity, offering jobs to umpires who now had no games to call. After the war, he set his sights on players.

Four former major-leaguers had played in the Mexican League in 1945, but the following year, Pasquel started to make his pitch to the game’s stars. By 1945, the Pasquel family fortune was estimated at around $65 million,19 and Pasquel was determined to use some of that money to lure top talent south of the border.

He offered Ted Williams, just back from the service, $100,000, more than twice what he’d made with the Red Sox. Bob Feller was also offered $100,000 a year. Hank Greenberg was offered $120,000.20 Phil Rizzuto was offered $50,000 a year. Pasquel even offered $50,000 annually to Happy Chandler to leave his job as commissioner of baseball and become commissioner of the Mexican League!

Despite Pasquel’s open checkbook, the stars of the day didn’t jump ship for the Mexican League. But some players did. It was estimated that 21 major-leaguers were on Mexican rosters for the start of the 1946 season, including Dodgers catcher Mickey Owen, Cardinals pitcher Max Lanier, White Sox pitcher Alex Carrasquel, and Giants pitcher Sal Maglie and outfielder Danny Gardella.

The league’s facilities left a lot to be desired – small stadiums with inferior locker facilities; travel not by train, but by bus (in some instances with other passengers carrying chickens). New York Times columnist Arthur Daley, admittedly with the benefit of hindsight, said the league was bound to fail, since it was “strictly a leaky-roof circuit with only one decent ball park.”21 But even he acknowledged that the Mexican League – and in particular, Pasquel’s open checkbook – threw a scare into the major leagues.

It started first with lawsuits. The Yankees and Giants both sought injunctions to keep Pasquel from signing their players (eventually, so too did the Dodgers). Then Commissioner Chandler issued a five-year ban for any player who jumped to the Mexican League. In turn, Pasquel alleged that the major leagues were a monopoly (a claim not necessarily without merit).

Eventually, baseball issued a report, named for Yankees executive Larry MacPhail. The MacPhail report led to wholesale changes including a minimum salary of $5,000 annually, a limit of 25 percent on salary reductions, establishment of a pension plan, and money for spring training expenses. The report even suggested that the reserve clause, which bound players to their teams even when they were not under contract, could be ruled unenforceable if taken to court.

In fact, Chandler’s ban against Mexican League players was taken to court, by Gardella. Although Gardella’s case was dismissed at trial, on appeal, the Second Circuit reversed the decision and returned the case to the trial court to determine if baseball had become interstate commerce, and was thus subject to federal anti-trust laws. In a concurring opinion, Second Circuit Judge Jerome Frank stated that the reserve clause was illegal and immoral.22 Before a new trial was held, and in order to avoid a potentially successful challenge to the reserve clause, owners settled the suit in 1949, lifting the Mexican League ban and paying Gardella $60,000.23

The Second Circuit’s opinion in Gardella v. Chandler suggested that the reserve clause was on shaky ground, which provided hope for Curt Flood’s suit against baseball over 20 years later.24 Thus, Pasquel had a hand in the sequence of events that ultimately led to free agency for major league players.

Ultimately, Pasquel’s pursuit was quixotic. Financial losses forced the cancellation of the league’s postseason. Pasquel claimed to have broken even in 1946, and even suggested he would put a team across the border in Texas the following year. But losses following the season, around $400,000, tracked almost identically with salaries paid to entice major leaguers south of the border. The facilities were never improved, and his fellow owners, nowhere near as deep-pocketed as he was, were not completely convinced that this was the right idea. Although he rattled the saber about signing American players again in 1948, Pasquel’s raid on major-league baseball ended after the 1946 season. Most of the players returned to their respective teams, after Chandler lifted the ban in 1949. But changes rippled through the years.

Pasquel’s life after his raids of the major leagues had a startling denouement. He and his brother Bernardo resigned as president and vice president of the Mexican League in 1948. The Mexican League reorganized in 1949, and while Pasquel maintained ownership of the Veracruz team, he was no longer actively involved in day-to-day league operations.

In 1951, Pasquel was injured in a hunting accident, and then hurt again when he was hit by a brick thrown by a fan at a Mexican League championship game in San Luis Potosí. Veracruz won the series, but Pasquel announced he was leaving baseball, which was already being supplanted by soccer as Mexico’s most popular sport. Pasquel disbanded the team and sold the baseball stadium.25 The Pasquels were out of the baseball business.

Pasquel’s friend Alemán left office at the end of 1952. One of the first actions by his successor, Adolfo Ruiz Cortines, was to take away a sweetheart oil distribution monopoly. Pasquel maintained his business interests but was no longer as prominent a figure in Mexico.

On March 7, 1955, Pasquel had to attend to business at his ranch in the Sierra Madre mountains. He departed by plane from Mexico City that afternoon, and after completing his work, he was set to take off at 9 p.m. that night. Pasquel had installed an asphalt landing strip at the ranch, but the strip relied on kerosene lights to illuminate it, for what was just the second night takeoff attempted from the ranch.26

Shortly after takeoff, the Lockheed Ventura brushed treetops and struck a mountain, killing all seven people on board, including Pasquel, who was a month short of his 48th birthday. An estimated 20,000 mourners lined the route from the church to the cemetery for his funeral. A month later, the Mexican League became part of U.S. organized baseball. “It will never be forgotten,” wrote the Mexico City newspaper Esto, “Even by generations in the distant future, that Jorge Pasquel, leading his family, made organized baseball in the United States tremble. He broke the color barrier and improved the game in Mexico.”27

No league has since mounted a challenge that compares with Pasquel’s. After the Dodgers and Giants left New York for California, there was talk of another league, the Continental League, but plans were quickly scuttled once expansion was announced to many of the proposed cities.28

Pasquel was elected to the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971, and his brother believed another hall should come calling, saying in 1983, “If the major league players had any guts, they’d make sure my brother Jorge was elected to Cooperstown for helping them gain their freedom.”29

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Sources

McKelvey, G. Richard, Mexican Raiders in the Major Leagues: The Pasquel Brothers vs. Organized Baseball, 1946. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland Publishing, 2006.

Virtue, John, South of the Color Barrier: How Jorge Pasquel and the Mexican League Pushed Baseball Toward Racial Integration. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland Publishing, 2008.

Jorge Pasquel file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Notes

1 Virtue, South of the Color Barrier: 156.

2 Dan Daniel, “Pasquel Goes After Whole Flock of Dodgers – And Draws the Bird,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1947: 17.

3 South of the Color Barrier. Irvin wrote the foreword.

4 William Fay, “Pasquel Associates Prefer Baseball Mexicano,” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1946: A1. Part of the Pasquel file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

5 “Jorge Pasquel is the Boss,” Life, June 24, 1946: 120. https://books.google.com/books?id=LkoEAAAAMBAJ&q=pasquel#v=onepage&q&f=true

6 South of the Color Barrier: 12

7 Gerald F. Vaughn, “Jorge Pasquel and the Evolution of the Mexican League,” The National Pastime, 1992.

8 The U.S.S. New Hampshire was one of the ships involved in the attack. Among the seamen was future Hall of Famer Sam Rice. Recounted in Mexican Raiders in the Major Leagues.

9 McKelvey, Mexican Raiders in the Major Leagues: 44.

10 Marty Appel, “The Mexican League Raids and the Last Full-Season Suspensions,” Hardball Times, reprinted on Appel’s website. http://www.appelpr.com/?page_id=460

11 Jorge becoming the most prominent Pasquel brother may have had more to do with his charisma than his business acumen. Bernardo, the oldest brother, had a more retiring personality but a larger role in the operation of the family’s business interests.

12 William Fay, “Pasquel Associates Prefer Baseball Mexicano.”

13 Mexican Raiders in the Major Leagues: 131-32.

14 South of the Color Barrier: 199.

15 Autocratic American League President Ban Johnson who, like Harding, had come from a central Ohio newspaper background, advocated it as a more civilized alternative to bullfighting. South of the Color Barrier: 28.

16 South of the Color Barrier:78.

17 South of the Color Barrier: 90.

18 South of the Color Barrier: 112.

19 South of the Color Barrier: 9.

20 Some accounts had Ted Williams receiving a literal blank check from Pasquel. Likely not coincidentally, players started to get raises. Stan Musial’s salary more than doubled from 1946 to 1947, from $13,500 to $31,000. Greenberg got a $30,000 raise.

21 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: South of the Border,” New York Times, January 31, 1952: 32.

22 Brad Snyder, A Well-Paid Slave: Curt Flood’s Fight for Free Agency in Professional Sports (New York: Penguin Group, 2006), 25-27.

23 Further reading: https://sabr.org/journal/article/danny-gardella-and-the-reserve-clause/. Gardella ultimately got one more major league at bat, with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1950.

24 A Well-Paid Slave, 97

25 South of the Color Barrier: 199.

26 South of the Color Barrier: 200.

27 South of the Color Barrier: 201.

28 New York Times baseball writer John Drebinger also noted that an independent baseball league looking for players to jump ship would have to contend with a new pension plan – one of the recommendations implemented from the MacPhail report. “City Seeks 3d Major Baseball League,” New York Times, November 14, 1983: 1.

29 Robert McG. Thomas Jr., “Sweetening the Pot,” New York Times, May 2, 1983: C2.

Full Name

Jorge Pasquel Casanueva

Born

April 23, 1907 at , Veracruz (Mexico)

Died

March 7, 1955 at San Luis Potosi, (Mexico)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.