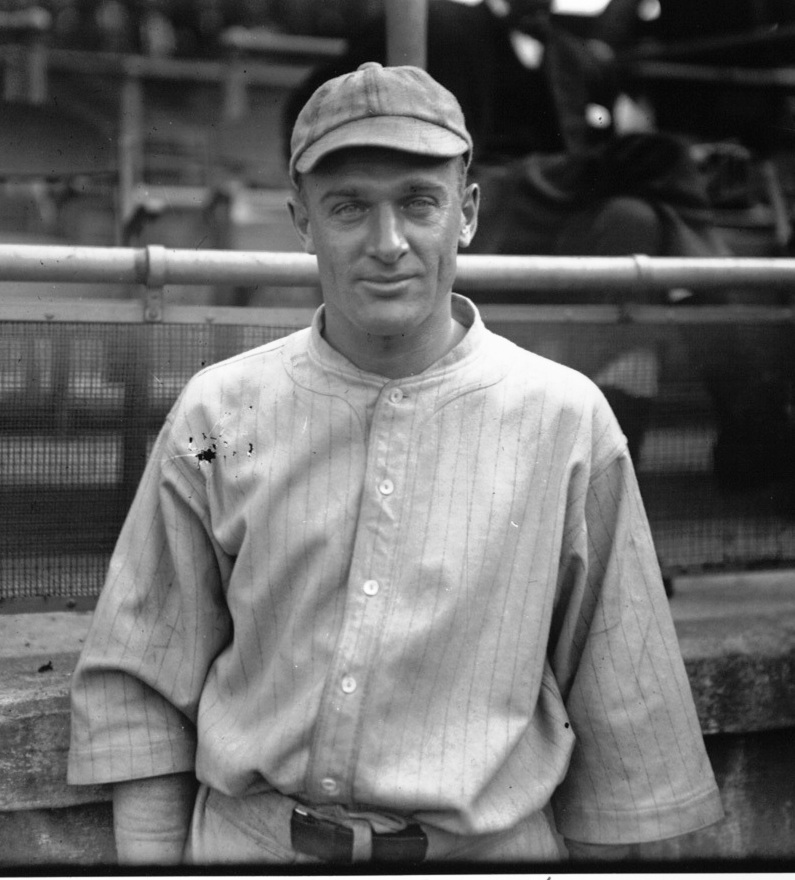

Larry Gardner

In the foothills of the northernmost Green Mountains, just 16 miles from Vermont’s Canadian border, the village of Enosburg Falls proclaims itself “Dairy Center of the World.” Its annual Vermont Dairy Festival attracts thousands of visitors, but its population of slightly over 2,000 is roughly the same as it was more than a century ago. Like many villages dependent on the undependable price of milk, Enosburg Falls is experiencing economic hard times. Every year the average age of its inhabitants creeps slightly upward as young people leave to escape life on the farm. The old folks hang on, recalling better times.

In the foothills of the northernmost Green Mountains, just 16 miles from Vermont’s Canadian border, the village of Enosburg Falls proclaims itself “Dairy Center of the World.” Its annual Vermont Dairy Festival attracts thousands of visitors, but its population of slightly over 2,000 is roughly the same as it was more than a century ago. Like many villages dependent on the undependable price of milk, Enosburg Falls is experiencing economic hard times. Every year the average age of its inhabitants creeps slightly upward as young people leave to escape life on the farm. The old folks hang on, recalling better times.

But Enosburg Falls fights to reclaim lost glory. In recent years an energetic village manager and board of aldermen have spruced up Lincoln Park, the quintessential village square, with its bandstand and fountain dating from 1897. One recent addition is a Vermont historical site marker commemorating the birthplace of Larry Gardner. A Civil War hero? An innovator of farming techniques? Hardly. Long considered the greatest baseball player to come out of Vermont, Gardner was the regular third baseman on four World Series championship teams, the Boston Red Sox of 1912, 1915, and 1916 and the Cleveland Indians of 1920.

Back in Larry Gardner’s day, Enosburg Falls was one of the most prosperous villages in Vermont. Dairy farming was more lucrative then, but the chief source of the village’s prosperity was the world-famous Dr. B.J. Kendall Company, manufacturer of a liniment called Kendall’s Spavin Cure. An alleged remedy for a disease that affects horses’ ankle joints, Spavin Cure became hugely profitable in the 1870s when the horse was the keystone of transportation.

Economic opportunity is undoubtedly what attracted Delbert Murancie Gardner to Enosburg Falls in 1872. The son of an Episcopal minister, Delbert came from St. Armand in the Eastern Townships of Quebec. He sought his fortune less than 20 miles from St. Armand, establishing himself in a shop near the Enosburg Falls railroad depot as a “dealer in groceries, provisions, dry goods, Yankee notions, etc.” Five years later, Delbert married a local girl, 18-year-old Nettie Lawrence, whose family claimed distant connection to George Washington and a great-grandfather who fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill. Delbert and Nettie had a son, Dwight Murancie, then a daughter, Glenna Maude. Their third and final child, William Lawrence, better known as Larry, was born on May 13, 1886.

Larry’s childhood days in Enosburg Falls were among his happiest. He sang tenor in the school quartet and spent many evenings playing guitar with an Italian storekeeper who accompanied him on the mandolin, the beginnings of a lifelong love of music. During the winter he skated, snowshoed and hunted, and at an early age developed a passion for fishing that lasted his entire life.

But Larry’s chief talent lay in team sports – or what little opportunity there was for organized athletics at tiny Enosburg Falls High School. “For lack of an organized leader, not much was done at football, although we had good material,” he wrote in his column in The Echo, a student magazine. “Basketball has created some excitement among the girls, but as yet the boys have not formed a team.” Larry captained the EFHS hockey club. But “the most popular sport with the townspeople as well as the school,” he reported, was baseball. The first records of Gardner’s diamond career date from 1902, his freshman year. In his junior year he pitched every inning of every game and batted an even .400. A 7-4 record prompted The Echo to claim that “we are the champion high school team in Franklin County.” With five starters returning, expectations ran high for Larry’s senior year.

In that season of 1905, Larry Gardner rose to what stardom a small town near the Canadian border could offer. The campaign opened with a disappointing 5-3 loss to Brigham Academy, but Larry brought the team back by pitching three consecutive shutouts. On May 20 he was finally scored on but struck out 13 in a 7-2 win. Two days later Larry pitched against Montpelier Seminary, and in 1943 he told a reporter that “of all the baseball I’ve ever been connected with, this particular game stands out most vividly in my mind.” Thirty-eight years after the game he recalled its details:

Going into the ninth inning we were leading 1 to 0. “Montpelier Sem” was at bat with bases full and one out. I really was in a tough spot then. The man at bat knocked a hard one that I fielded. I forced the man out at home. The catcher threw to get the man out at first, making a double play and ending the ball game. I can tell you, the men at the corner drug store talked over this game for weeks.

Enosburg Falls celebrated Gardner’s fourth shutout of the season with a band concert, bonfire, and promenade, the Montpelier boys remaining overnight to enjoy the festivities.

Larry tossed his fifth shutout in seven games against Newport High School on May 27. More than two weeks later he closed the season with a 10-1 win over Newport, which “would have been a shutout, but for a wild throw in the first which let in Newport’s only run.” The team’s 7-1 record, according to the Enosburg Standard, clinched the high school championship of Vermont. “The local team has worked hard, has played clean ball, and has made a great 1905 baseball record for Enosburg High School,” it proclaimed, “and is entitled to all the honor and credit which the state championship gives them.” In eight games on the mound Larry Gardner yielded only eight runs, the majority of which most likely were unearned. He was no weak hitter, either, finishing with a batting average of .432, second-highest on the team.

The Missisquoi River cuts through the heart of Enosburg Falls, providing a summer playground for the children of the village. In 1904 Larry Gardner wrote an essay about it that was published in The Echo:

A DARING ADVENTURE

It was one of those warm, pleasant days of July when nearly every youngster of the village was down at the river, swimming. They were doing all sorts of dangerous tricks, but none so dangerous as the one I had in mind to do that afternoon if I could get one of the boys to go with me.

It was an easy matter to persuade one of the lads, even more adventurous than myself, to fall in with my plan; so after spending the early part of the afternoon at the river, we left our companions and started off.

The plan was to try to climb a steep rock just below the bridge. So far as we knew no one had ever scaled it, and a dog that had been thrown off it had been instantly killed. The rock was on the very edge of the river, and extended straight up into the air for about one hundred feet. The water below was about three feet deep, out of which protruded huge bowlders and sharp fragments of rocks.

It was difficult starting because the rock bulged out, making a shelf about six feet from its foot. I helped my companion upon this shelf and he pulled me after him. The rest of the way was straight up. There was once in a while a little crevice, which helped us along, but progress was slow. We had gone up over half way when we came to a crumbly-looking part of the rock. I put the fingers of one hand into a crevice and held myself up by the other. I then started to pull myself up, when a rock broke away and came tumbling down, landing upon my left hand. As this was the only hand with which I was hanging on, I almost let go. Had I done so, I should surely have rolled down with the rock, which, quicker than a flash of lightning, went splashing into the water beneath. But a small rock had rolled out of the way, which gave us a good foot-hold; and as the rest of the way was easy, we soon reached the top.

I have never attempted to climb the rock since; but I have often stood on its top and wondered how I ever had the nerve to attempt to scale its dark surface.

In prophesying the fates of the next year’s editorial staff in that same issue, a clairvoyant schoolmate wrote: “This is Mr. Lawrence Gardner, the future athletic editor of The Echo. Fame is sure to be his, if he isn’t killed first.”

The summer following Larry’s graduation from high school, four of the area’s semipro teams banded together to form the Franklin County League. Larry’s older teammates appointed him assistant captain of the Enosburg Falls team – called the Spavin Curers or Liniment Makers by local newspapers. The team from St. Albans was known as the Railroaders because the town was the home of the Central Vermont Railway. Swanton was called either the Fish Hatchers, because it was home to a fish hatchery, or the Bullpout, after the gamefish. Newspapermen dubbed the Richford team the Chinese Spies because the border town contained a US Customs detention center for illegal Chinese immigrants.

In a season marred by contract jumping, frequent protests, and a brawl that resulted in criminal charges against participating players, Larry Gardner stood out as the Franklin County League’s top all-around talent. He played shortstop and pitched, and after one outing the St. Albans Messenger coined him a new nickname: “‘Larry’ Gardner, the child marvel from Enosburg Falls, pitched rings around the local baseball players yesterday at the local league grounds.” From that point on Franklin County newspapers frequently referred to Gardner as the child marvel. Despite his heroics, the Spavin Curers (12-10) finished in third place, two games behind arch-rival Richford (15-9).

Though the rough-and-tumble circuit lasted only that one season, it had a lasting impact on Larry Gardner’s life. Several “ringers” from the University of Vermont baseball team played in the Franklin County League, and they got him interested in attending UVM. In late September 1905, the 19-year-old Gardner became one of 82 men and 30 women, only 16 of whom were from out of state, to make up UVM’s Class of 1909. In those days a year’s tuition and expenses at UVM could run as high as $350, but with a loan from brother Dwight, who was working in Ohio as a traveling salesman for the Dr. B.J. Kendall Company, Larry scraped together the money. Even friends helped defray the enormous expense; the Saturday before he left for Burlington, 25 of them met at his home and presented him with a $5 gold piece as a farewell remembrance.

Larry majored in chemistry at UVM, his goal to go out west to the gold mines and work as an assayer. According to The Ariel, he was the “peerless songster of the chem. lab., and because he is very mischievous Nate has required him to change his seat quite often in lectures.” (Nate was Professor Nathan Merrill, dean of the chemistry department, who had been teaching at UVM since the year before Gardner was born.) Larry was popular among his classmates; The Ariel called him the “‘Sunny Jim’ of the class” and stated that “[his] presence is a sure cure for the ‘blues.’”

Though freshmen baseball players typically played for UVM’s second team or their class team for at least a year, Larry was one of two first-year students to make the varsity – the other being fellow future major-leaguer Ray Collins. That season UVM christened a new baseball field, called Centennial Field because the purchase of the land on which it was built was announced on July 6, 1904, at the conclusion of a three-day celebration of the 100th anniversary of UVM’s first graduating class. After two years of clearing and grading, Centennial was finally ready for the home opener against Maine on April 17, 1906.

Batting leadoff and making his debut at third base (he had played right field in the opener down at Harvard), Gardner made an out in his first at-bat, hence becoming the first UVM batter in Centennial Field history. Still he managed a pair of hits and his second stolen base of the season in a 10-4 victory. It was an auspicious opening for the new field, the Free Press reporting that “attendance was good, the cheering enthusiastic and the day ideal for base ball barring a bit too much breeze.” Vermont’s vaunted freshmen distinguished themselves: “Fielding features were contributed by Gardner and Collins, new men this year in the varsity line-up.”

The largest crowd of the 1906 season climbed college hill on May 1 to take in the game against Holy Cross, winner of eight in a row before losing at Dartmouth on the way to Burlington. Four players from that Holy Cross team went on to the majors: Within 10 weeks catcher Bill Carrigan and left fielder Jack Hoey joined the Boston Red Sox; Jack Barry signed with the Philadelphia A’s in 1908 and become the shortstop in Connie Mack’s famous “$100,000 Infield”; and first baseman John Flynn, who had played in the Northern League in 1904, smashed six home runs as a Pittsburgh Pirates rookie in 1910. With Larry Gardner at third base and Ray Collins in right field for Vermont, the Holy Cross game featured six future major leaguers.

Centennial Field’s bleachers were filled to overflowing with students shouting themselves hoarse. Under freshmen rules, all first-year students were required to attend “smokers” in the gymnasium to learn the college yells and songs. Those rules also mandated attendance at home athletic contests – hardly necessary since games were considered major social events. On this day the Holy Cross “Big Four” were held to three hits in 15 at-bats as UVM won easily, 9-3. Afterwards students thrilled to the traditional tolling of the college bell in the Old Mill belfry.

Then as now, UVM students knew how to celebrate. They marched 300-strong down College Street headed by the college drum corps. When they arrived at the train station, they gave a rousing send-off to Gardner and his teammates, who took the 8:15 train to Rutland where they spent the night en route to the next day’s game against Williams College. The mob had achieved its main objective, but it was having too much fun to disband. The Free Press described the rest of its activities:

On the return march from the depot, a happy thought struck the boys — they must have a bonfire to finish up with. What better fuel than the unsightly shed which was annexed to the “hash house,” so long an eyesore to those who love to see the campus kept beautiful. The shack was quickly demolished, the debris was carried well out in the center of the field and the fatal torch applied. The boys gathered around the big fire and spent the remainder of the evening in singing songs, cracking jokes, and telling stories, breaking up about 10:30 o’clock well pleased with their celebration.

After batting safely in each of his first 10 games as a collegian, Larry Gardner led the UVM team with a .350 batting average. The rest of his season was a disaster. In his last seven games, he batted .148 and committed 10 of his season’s total of 15 errors. On a team that combined for an .896 fielding percentage, Gardner’s .769 was worst among regulars. For the season he batted .269, tied for fourth on the squad. On the positive side, he did steal a team-leading nine bases.

In Gardner’s era, playing independent baseball during summers was a legal way for college players to defray school year expenses. Tom Hays, the UVM coach, was also in charge of stocking Burlington’s team in the Northern League, probably the top independent circuit in the country. It was a tradition to announce the players’ names at Burlington’s Base Ball Carnival, an annual event to raise money for uniforms and equipment. “[T]he reading of the names at the fair last evening was heartily received,” the Free Press reported in June 1906, but the last name read, “to be given a trial as utility man,” drew a particularly hearty reception. It was Larry Gardner, “whose brilliant plays for Vermont during his first year in college have attracted much attention.”

For the summer Larry boarded at 138 Colchester Avenue, sharing the house with Doc Hazelton, Burlington’s veteran first baseman, and himself a future big leaguer. Other teammates who went on to the majors included catcher Bob Higgins, a former Brown University standout who played parts of three seasons with the Cleveland Naps and Brooklyn Superbas; pitcher Ray Tift, Higgins’ batterymate at Brown who appeared in four games for the New York Highlanders in 1907; and Harry Pattee, who stole 24 bases in 74 games in his best season with the Brooklyn Superbas in 1908. In all, no less than 25 former or future major leaguers played in the four-team Northern League in 1906, but even in that heady company Gardner held his own. He became Burlington’s regular right fielder and batted .296 as the team walked away with the Northern League’s last pennant.

The following spring Larry received his first attention from a major-league scout. George Winter, a pitcher who had twice won 16 games in a season for the Boston Americans, was married to a woman from Burlington and lived at 70 Front Street during the offseason. To pass the time before spring training, Winter watched the UVM team work out in the cage and dubbed Gardner a prospect. Larry played shortstop for UVM in 1907. He was batting .400 after 11 games when an “inexcusable accident” occurred at Centennial Field in the third inning of a game against Massachusetts Agricultural College on May 17:

“O’Grady knocked a high fly into short left field and Higgins and Gardner both went after it, no coaching being evident. The men came together with terrific force, and both were stretched out almost senseless. Drs. Cloudman and Beecher took the cases in hand and it was discovered that Gardner had sustained a broken collar bone, while Higgins, though not considered dangerously hurt, was reported last night to be delirious and in a more serious condition than Gardner.”

When it was announced that Larry would miss the remainder of the season, UVM’s student newspaper, The Cynic, decried his loss: “Gardner will sorely be missed on the team. He was strong at the bat and wonderful at base running, his fielding was well nigh errorless, while his throwing was swift and sure as fate.” Without Larry in the lineup, UVM lost its next three games and finished with a 10-7 record. Though he missed a good portion of the season, his teammates nevertheless elected him captain for his junior year. He was also elected president of the junior class for the coming school year.

By June 30 Gardner had recovered sufficiently to join his UVM teammates, who were playing summer ball in Newport, New Hampshire. As if to answer any question whether his collarbone was fully mended, Larry smashed two home runs to lead Newport to a 5-3 win in its Interstate League opener against Randolph. A couple of weeks later he played a brief but full-fledged stint in organized professional baseball. When the Burlington team dropped out of the Class D Vermont State League, the UVM nine stepped in as replacements. “Many have felt all along that the Vermont team was the one to uphold the Burlington end on any baseball proposition, made up as it is of so many local favorites,” the Free Press wrote. The collegians fared well, holding the second-best record (4-3) when the league disbanded for good on July 27.

With still a month to play that summer, both Larry Gardner and Ray Collins joined the Bangor Cubs of the Maine State League. Batting cleanup, Gardner established himself as Bangor’s best hitter as the Cubs captured the 1907 pennant. His average of .371 (39 for 105) led the league, and both he and Collins were unanimous selections to the All-Maine team. By this time both players’ actions were followed closely by numerous scouts, especially Fred Lake of the Boston Americans, and newspapers frequently mentioned that they were considered “big league material.”

By the spring of 1908 both Gardner and Collins were receiving offers from major-league clubs. In an April 11 letter, Connie Mack tried to induce Larry to sign a contract immediately for $300 per month, with one month’s advance upon signing, and join the Athletics after UVM’s season. To allay Gardner’s fears that signing a professional contract would make him ineligible for college ball, Mack wrote that ”it will not be necessary for anyone but you and I to know that you have signed.” During the course of UVM’s season Larry also received several offers by telegram from John Taylor, president of the Boston Americans (at that point just starting to be called the Red Sox).

Gardner rebuffed those offers and remained at UVM for his junior season. Bad weather caused a lack of outdoor practice and a poor 2-4 showing on the southern trip, but the team rebounded to finish with 15 wins, eight losses, and two ties against the toughest schedule UVM had played since the days of Bert Abbey and Arlie Pond. Calling them the “champion baseball team of New England,” the Free Press wrote, “Capt. Gardner, the hardest hitting man on the team, has been batting at a .300 clip, and it would be hard to find a better shortstop.” Nonetheless he was named the third baseman on the Springfield Republican’s All Eastern Nine, making room for Holy Cross’ Jack Barry at shortstop.

When Red Sox utility infielder Frank Laporte went down with an injury in late May, the Red Sox stepped up their efforts to sign Gardner. After UVM’s season ended with a win over Manhattan College on June 4, Larry’s brother, Dwight, and mother, Nettie, came to Burlington to assist Larry with his difficult decision. Signing would mean he could finally repay Dwight’s generous loan, but it would also force him to give up his senior season at UVM. Finally Larry succumbed. After final examinations, he reported directly to St. Louis, where the Red Sox were in the midst of a western road trip.

Larry remembered feeling “like a lost kid from the green hills” that summer. “Before this time I’d never seen a big league game,” he said. “I’d been to the city a few times and while there held on to the hand of an older person for fear of getting lost.” If he was nervous, it didn’t show in his initial performance. Larry saw his first action on June 22 in an exhibition game in Rochester, New York, as the team made its way back to Boston. He homered in his first at-bat and played shortstop in “whirlwind fashion,” handling six chances without error. Three days later, in his first official major-league game, Larry replaced an injured Harry Lord in extra innings and ripped a game-winning double to beat the Washington Senators at Boston’s Huntington Avenue Grounds.

On June 27 he appeared in the starting lineup for the first time as the Red Sox took on the New York Highlanders at Hilltop Park in the Bronx. Playing third base and batting fifth, he went 0-for-4 with an error as Boston lost, 7-6. To make things worse, Larry was “bunted to death” by Wee Willie Keeler, who had two bunt singles among his four hits. That night Cy Young, the legendary pitcher, invited Larry to join him at the hotel bar. The 41-year-old veteran consoled the 22-year-old rookie by sharing a bottle of a rare rye whiskey called Cascades. (In his next start, Young, at the time the oldest pitcher in the majors, tossed the third no-hitter of his distinguished career.)

Larry had appeared in three official games and was batting an even .300 when “Taylor, the owner of the club, made me a proposition: ‘stay with the Red Sox and gain experience by watching or go to Lynn where there’s a place open for a shortstop.’” Larry chose to play regularly, reporting to the New England League’s Lynn Shoemakers on July 15. To make room for him, Lynn’s regular shortstop, Barton, moved to second base, and 45-year-old Jimmy Connor was forced to the bench. The former regular second baseman of the 1898 Chicago Orphans took no offense; years later Larry said that Connor “probably helped him as much as anyone to make the big time.” In 61 games for Lynn, Gardner batted .305 and showed “all the earmarks of another Harry Lord.” In September the Red Sox invited him to rejoin the team for another western road trip, but Larry opted to return to UVM for the fall semester.

“With a little extra money in my pocket my senior year I lived the life of Reilly,” he remembered. “On occasion I’d even eat at Dorn’s Restaurant, a high-class restaurant in town at that time. Heretofore I had eaten at any hash house.” For the second straight year Larry lived in the Delta Sigma house at 342 Pearl Street, which was built in 1800 by Horace Loomis but sold to Elbridge Adsit as an investment property in 1907. Gardner joined a long line of distinguished guests that included Henry Clay and President William Henry Harrison.

Come spring, Larry watched from the bleachers as Ray Collins led the UVM baseball team to a 13-9 record. Final exams ended in mid-June but commencement festivities did not start until June 26, so Larry went down to Boston and actually managed to get into a game. On June 23, 1909, after replacing Harry Lord at third base in a game against the Highlanders, Larry tripled and scored in his only at-bat. A couple of days later he came back to Burlington for graduation. Only 59 of the 112 students who started at UVM in the fall of 1905 managed to earn diplomas, but Larry was one of six to receive a B.S. in chemistry. Returning to Boston, he appeared in only 18 more games for the Red Sox in 1909. With Lord a fixture at third and Heinie Wagner at shortstop, Larry spent most of his time on the bench. He performed well when given the opportunity, batting .297 with a .432 slugging percentage.

In 1910 a position opened up in the Boston infield when second baseman Amby McConnell was stricken with appendicitis only 10 games into the season. Larry filled in even though he had never really played second base. His inexperience showed on one occasion when he took a throw in the baseline with Ty Cobb sliding in. The Georgia Peach could have cut Gardner to shreds, but instead he slid around him and was tagged out. Walking off the field, Cobb turned to Wagner and said, “Tell the kid I won’t give him a break like that again.” But for the most part Larry performed admirably, batting .283 in 113 games and winning accolades for his fielding. One sportswriter went so far as to call him “one of the best second basemen in the country.” Gardner’s development allowed the Red Sox to trade McConnell to the Chicago White Sox.

After spending the offseason in Enosburg Falls ice skating, taking long hikes, and hunting (21st century residents of the house at 14 School Street found several of his old Vermont hunter’s licenses in the rafters), Larry reported to spring training in Redondo Beach, California, with new confidence in 1911. He entertained newspapermen and teammates alike with feats of ventriloquism. “Larry converses from his stomach and keeps the other players guessing from what direction the talk is being directed,” wrote one reporter. He also sang baritone in the Red Sox barbershop quartet, which included pitchers Marty McHale (first tenor) and Buck O’Brien (second tenor) and first baseman Hugh Bradley (basso). The quartet was good enough to tour the Keith’s vaudeville circuit for two winters at $500 per week, though Larry never traveled with them. “He used to sing around Boston but we used a ringer named Bill Lyons on the road,” said O’Brien.

Despite the speed he showed when he first took over at second, Gardner seemed slow and unable to cover territory in 1911. Manager Patsy Donovan was searching for a third baseman to replace Harry Lord, who had been sent to Chicago the previous year in the same trade as McConnell. At midseason he shifted Gardner to third. “Can it be possible that Larry Gardner has been out of position all this time?” wrote Ring Lardner. “He was certainly a success as a second sacker, but right now it would be hard to convince the uninformed observer that he hadn’t been playing third base for years.” A Boston scribe wrote, “Third base has not been played so well in Boston since the days when Jimmie Collins was in his prime.” After the season Washington manager Jimmy McAleer selected Gardner as the third baseman on a team of American League all-stars. They played a series of exhibitions against the Philadelphia Athletics, who were preparing for the 1911 World Series.

During the 1912 season Gardner and his best friend on the Red Sox, Harry Hooper, lived together in Winthrop on Boston’s North Shore. During mornings the two players viewed the bay and took dips in the salt water before driving to brand-new Fenway Park in their four-cylinder Stutz roadster, which they co-owned. They cooked shellfish by digging a hole in the sand, throwing in hot rocks and covering the hole with seaweed. Once Larry attempted to duplicate the trick for his family in Enosburg Falls, using chicken instead of shellfish and hay instead of seaweed, but it tasted so awful they couldn’t eat it.

That 1912 season was a breakthrough year for both the Red Sox and Larry Gardner. Boston ran away with the American League, besting second-place Washington by 14 games, and Gardner hit .315 with a team-leading 18 triples. But on September 21, in the eighth inning of a meaningless game in Detroit, he was injured diving for Donie Bush’s grounder down the line. The ball hit the little finger of his bare right hand, snapping it at the first joint and causing the bone to protrude through the flesh. Larry went home to Enosburg Falls to recuperate. Initially it was feared that he might miss the World Series, but he returned to the lineup on October 6 for a couple of games against Philadelphia.

Playing with his fingers taped together, Larry performed poorly in the first three games of the 1912 World Series against the New York Giants. In Game Four at the Polo Grounds he finally broke out of his slump, blasting a single and a triple and scoring two runs in a 3-1 Boston victory. In the next three games his bat again fell relatively silent, though in Game Seven he hit Boston’s only home run of the Series. Then came the eighth and deciding game at Fenway Park (Game Two had been a tie). It was one of the most dramatic games in baseball history, and one for which Larry Gardner will forever be remembered.

The game was tied at 1-1 after nine innings. In the top half of the 10th the Giants grabbed a 2-1 lead. With Christy Mathewson on the mound for New York, Boston’s chances appeared slim. Clyde Engle led off the inning by lifting a soft fly to center field, but Fred Snodgrass pulled his infamous muff. Hooper made the first out and then Steve Yerkes walked. With runners on first and third, Tris Speaker lifted a lazy fly in foul territory near the first base coach’s box, but for some reason Fred Merkle didn’t make much of an effort. He just stood watching as Chief Meyers, the Giants catcher, plowed down the line and tipped the ball with the end of his mitt. Given new life, Speaker singled to score Engle with the tying run. With runners at second and third, Mathewson walked Duffy Lewis intentionally to load the bases. Up to the plate stepped Gardner.

Realizing that Mathewson was working him to hit a low ball, Larry allowed two balls to go by before he swung and missed at the third pitch. A walk meant forcing in the winning run, so Matty couldn’t afford to be cute. His next pitch was over the inside corner, well above the knee. Larry swung and a shout went up as the ball headed for deep right field. “I was disappointed at first because I thought the ball was going out,” Larry remembered, “but then when I saw Yerkes tag up, then score to end it, I realized it meant $4,024.68, just about double my earnings for the year.”

After a celebration the next day at Boston’s Faneuil Hall, Larry returned to a hero’s reception in Enosburg Falls. His train arrived bedecked with red lights from engine to rear coach, and explosions of railroad torpedoes went off every few rods as it swept into the village. Fully 500 people were on hand to greet him. After alighting, Gardner was escorted to the car of honor, which was beautifully trimmed with American flags, bunting and “red sox.” Seated in the car with Larry were his father, Delbert Gardner, and the whole reception committee. Sixteen autos followed in a procession through the village. In front of the Perley block on Main Street, the Honorable Olin Merrill, chairman of the Vermont Republican Committee, made a speech lauding Gardner as a “clean type of ballplayer of whom any community might well feel proud.” After Larry made a few short remarks, expressing his appreciation, the procession reformed and escorted him to his home at 14 School Street.

Gardner’s presence was much in demand during the week following the World Series. At a reception in Enosburg Falls sponsored by the Philemon Club, Merrill spoke again, this time focusing on the significance of a small state contributing two members to the champion team of the world (he saw it as “evidence of the sterling qualities of Vermont stock”). Special guest Tim Murnane of the Boston Globe talked about how the earnings of baseball players all over the country were a great benefit to rural communities, as players generally hailed from those parts and spent their money there.

The next night Larry, Ray Collins and 1912 Olympic gold medal winner Albert Gutterson were feted at Burlington’s Hotel Vermont. Among the 450 in attendance were Governor Fletcher, Mayor Burke, and some 300 UVM students. Each of the guests of honor received a silver loving cup presented by UVM President Guy Potter Benton. Gardner’s was inscribed as follows:

From The City of Burlington

and The University of Vermont,

to “Larry” Gardner

in loving appreciation of the deserved

fame he has won for himself, for his

city and his alma mater as third

baseman for the Boston Americans,

world’s champions of 1912.

Whatever became of the ball that Larry Gardner belted to Josh Devore for the sacrifice fly that won the 1912 World Series? The bat is on display at UVM’s Gutterson Fieldhouse, but the whereabouts of the ball is a mystery.

Initially it was in the possession of Thomas W. Watson, who worked the turnstiles at Fenway Park during the 1912 World Series. After Steve Yerkes crossed the plate with the winning run, Chief Meyers chucked the ball aside and Watson pocketed it. That night he went to the Hotel Putnam and presented it to Gardner. In exchange, Larry gave him a brand-new ball autographed by the whole Red Sox team, with the addition of Mayor John F. Fitzgerald’s signature.

When Larry arrived at Enosburg Falls, both the bat and the ball were displayed at the office of the Enosburg Standard. Eventually Larry donated the bat to the UVM athletic department, but the Gardner family has no idea what happened to the ball.

Larry Gardner was on top of the world that winter. He was named the first-team third baseman on Baseball Magazine’s All-America team, the first of four such selections he earned over the course of his career. Then he signed a three-year contract with the Red Sox. Still Larry remained his same humble self. “He has a disposition as sweet as the wild flowers that grow on the mountains of Vermont,” wrote Tim Murnane. A few years later, T.C. Cheney wrote that “there is no more modest, unassuming or clean young man in [baseball] than our Green Mountain boy, who is an honor and credit to the game and his state.” Larry also carried a reputation as an intellectual: “Off the ball field Gardner prefers to read an essay on Shakespeare’s poems than to discuss baseball,” wrote one reporter.

On July 11, 1914, Larry Gardner collected three hits to make a winner of a rookie southpaw in his first big-league pitching appearance – a young man by the name of George Herman Ruth. “One of the first times I saw Ruth, the guy was lying on the floor being screwed by a prostitute,” Larry said. “He was smoking a cigar and eating peanuts, and this woman was working on him.” Perhaps hoping some of Gardner’s gentility might rub off on the Babe, the Red Sox assigned Larry as his roommate. “What’s it like to room with Babe Ruth?” Larry was often asked. “I don’t know,” he replied. “He never stays with me in the room when I’m on the road. He’s always living with women.”

In 1916 Ruth matched up five times against Walter Johnson, whom Gardner always credited as the greatest pitcher he ever saw. The Babe triumphed in four games, two by 1-0 scores, and in the last of them Gardner’s single in the 13th inning won the game. “How can you figure hitting? I still can’t,” Larry said. “One pitcher I never could touch was Eddie Plank. I got one hit off him in my entire career – and it won a ballgame. Yet I always could hit Walter Johnson and he was off in a class by himself. I did it by just punching the ball to left field.”

After hitting .259 and a career low (as a full time player) .258 in the previous two seasons, Larry rebounded in 1916 to hit .308 despite playing with a dislocated big toe. His batting average was fifth best in the American League, behind only Tris Speaker, Ty Cobb, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and Amos Strunk. With Speaker gone to Cleveland, Gardner became the biggest bat in Boston’s lineup as the Red Sox won their second consecutive AL pennant. Then he enhanced his reputation as a clutch player by smashing two home runs in the 1916 World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The first one came in Game Three at Ebbets Field. “I hadn’t been hitting and I was really mad,” Gardner remembered. “Jack Coombs was pitching for the Dodgers and he was a helluva pitcher. He broke off a curve on me, a lefty hitter. I started to swing and tried to stop because I thought it was a bad pitch, but I was committed too far and had to go through with it. I even had my eyes shut. When I opened them, I saw the ball going over the wall. Can you believe that – hitting a home run with your eyes closed?”

In Game Four, with two men on base and Boston down 2-0, Gardner hit a fastball from Rube Marquard for an inside-the-park homer, giving the Red Sox a 3-2 lead they never relinquished. “That one blow, delivered deep into the barren lands of center field, broke Marquard’s heart, shattered Brooklyn’s wavering defense, and practically closed out the series,” wrote Grantland Rice. Boston went on to win in five games, and Larry Gardner was considered the hero of the Series. As Tim Murnane put it, he had “a way of rising to the occasion as a trout rises to a fly in one of his favorite Vermont streams.”

Despite his heroics, Larry couldn’t get a raise. The most Red Sox owner Harry Frazee offered was to bring Larry’s new bride, the former Margaret Fourney of Canton, Ohio, to spring training at Hot Springs, Arkansas, as the club’s guest. “I told my wife to take 40 baths a day and ride horses the rest of the time,” Larry said. “We really stuck Harry on that one!” In 1917 his batting average fell from .308 to .265, giving the Red Sox an idea that he was slipping after 10 years of service.

On January 10, 1918, Boston traded Gardner, reserve outfielder Tillie Walker, and backup catcher Hick Cady to the Philadelphia Athletics for first baseman Stuffy McInnis. “While the loss of Walker and Cady might be accepted with cheerful resignation,” wrote Paul Shannon in the Boston Post, “the going of Gardner, one of the most powerful hitters on the team for years, one of its most dependable members and a model player in every way, will be severely felt.” Philadelphia writers, on the other hand, welcomed news of the trade. “The report that Gardner has passed the zenith of his career and is on the decline is all camouflage, probably designed to placate the Boston fans, with whom he was extremely popular,” wrote one of them. “His moral and corrective influence upon the younger men of whom the team will mostly consist this year should be invaluable.”

The A’s were in the midst of an AL-record seven consecutive seasons in last place, and though they finished in the cellar again in 1918, the 32-year-old Gardner proved that he wasn’t washed up by batting .285. Though the Red Sox won another World Series, they missed Larry’s presence. “Gardner’s absence last year almost cost the Red Sox the world’s championship,” wrote a Boston reporter. “The Sox tried out more than a dozen third sackers in an attempt to fill his shoes.”

But Connie Mack was continuing his youth movement, so before the 1919 season he traded Gardner, pitcher Elmer Myers, and outfield prospect Charlie Jamieson to the Cleveland Indians for slugging outfielder Braggo Roth. The Indians had finished second in 1918 with a weak platoon of Joe Evans and 37-year-old Terry Turner at third, so Cleveland writers thought the deal strengthened the team considerably. Gardner-for-Roth straight up would have been fair, they thought, but this trade was a steal. Reunited with former Red Sox teammates Tris Speaker and Joe Wood, Larry played every inning of every game, hit an even .300, and led the team with 79 RBIs.

In 1920 Gardner did even better, batting .310 with a team-leading 118 RBIs to help Cleveland finish on top of the American League. It had taken 42 years; of the 11 cities with major-league franchises, Cleveland was the 9th to win a pennant in the 20th century. Larry’s leadership proved instrumental. When shortstop Ray Chapman was killed by a pitched ball in August, 21-year-old Joe Sewell was called up from the minors in the middle of a tight pennant race. Sewell, who had played very little shortstop, was extremely nervous. “Larry Gardner helped me a lot,” he remembered. “He talked to me all the time when we were in the field, trying to steady me.” The rookie batted .329 down the stretch, the start of a Hall of Fame career.

Cleveland went on to win the 1920 World Series, and on a road trip to Washington during the 1921 season the Indians attended a White House reception to receive congratulations from President Warren Harding, who was from Ohio. When it was Gardner’s turn to shake hands with the President, Harding said, “I know you are a good player, young man, because way back in the early ’80s I knew a player by that name. He was with Cleveland in the old National League and was a mighty good man.” Gardner drew a laugh when he said, “That was just about the time I was breaking in.” Though 35, Larry had his best season ever in 1921. He established career highs for batting average (.319), runs (101), hits (187), doubles (32), and RBIs (120).

Hampered by nagging injuries, Gardner was not quite as good in 1922, though he still played in 137 games and batted .285. He considered retirement when the Indians bought minor-league phenom Rube Lutzke, a third baseman, but Speaker persuaded him to come back and serve as coach and occasional pinch-hitter. Over the course of his last two seasons, 1923-24, Larry appeared in a total of only 90 games, playing the field in only 33.

Larry Gardner had always been concerned with his career after baseball. In his early days with the Red Sox he had invested in a Cape Cod cranberry business, but an early frost one year ruined the harvest and destroyed the company. After that experience Larry went into the automobile business in Enosburg Falls. With his partner, Francis Smith, whose wife was a cousin, Larry owned a garage and Willys-Knight dealership. But when the time finally came to devote all of his attention to another occupation, he couldn’t leave baseball behind.

In 1925 Larry managed Dallas of the Texas League, taking charge of a “mixture of indifferent and ‘mean’ ball players,” according to one reporter. Though the team finished a respectable third (85-66), Gardner quit before the end of the season, giving his wife only one day’s notice that they were leaving. The next two years Larry managed Asheville of the South Atlantic League. In 1926 the club won a league-record 15 consecutive games en route to a second-place finish, but in 1927 the team fell to fourth. Larry Jr. remembers his father’s chief complaint about the South: “Those were the days before refrigeration, and he always said it was hard to find ice cream.” After the 1927 season Larry returned to his garage and automobile business in Enosburg Falls. Margaret hated it there and was relieved when Larry joined the physical education department at the University of Vermont in 1929. Mr. and Mrs. Gardner and their two young sons lived in a rented house on Brookes Avenue, the street where Ray Collins grew up.

In 1932 Gardner became head baseball coach at UVM. He stressed sportsmanship ahead of winning – his overall record in two decades of coaching was a lackluster 141-166 – and well-rounded students over specialized athletes. “I guess he liked the team to win, but all I remember was how warm and human he was with the players,” said Larry Jr., who served as batboy. Nothing captures the essence of Gardner’s coaching philosophy better than a letter he wrote to President Stanley King of Amherst College on May 13, 1938 (coincidentally Larry’s 52nd birthday):

Dear Sir:

I am writing you a somewhat belated letter to express to you the keen pleasure our boys experienced at Amherst on April 21st when we met your Amherst team in a baseball game. While we lost the game, we gained something much more valuable than is expressed by winning or losing.

In the ten years I have been connected with baseball at Vermont, I can honestly say that I never saw our boys more impressed by spirit, gentlemanly conduct, and treatment than was given and exemplified by your students.

In the thirty years of my experience in baseball, this was truly the highlight and it pleases me to hand this observation on to you.

The boys join me in expressing our gratitude to you and the Amherst men.

Three days later he received this reply from President King:

Dear Mr. Gardner:

I would not be honest if I did not say that I am deeply touched by your letter of the 13th. The qualities which you stress in your letter are of course the qualities you and we are trying to develop in our boys in the playing of competitive sports. They are the qualities which seem to me most important in our staff. The teams that you coach at Vermont and which Paul Eckley coaches here may win or lose in individual games but the qualities of sportsmanship which the boys learn from their coaches and their fellows are among the most important by-products of our college education.

I watched the Vermont game from the stands myself and congratulate you on the fine boys on your team. The score of two to one was as close as a score can be. Again my warm appreciation for your letter.

In addition to his coaching duties, Larry Gardner was named UVM’s athletic director in 1942, and he held both positions until his retirement from the university in 1952. During the 1940s he also served as commissioner of the independent Northern League and as a part-time scout for the Boston Braves. After his 1952 “retirement,” Gardner fished frequently and worked a regular schedule at The Camera Shop on the top block of Church Street in downtown Burlington.

Gardner and his family lived a comfortable life in Burlington. They spent summers at a spectacular camp on Colchester Point, surrounded by cedars and situated on a rocky bluff overlooking Lake Champlain, with stairs leading to a quarter-mile stretch of sandy beach. Puffing on a cigar or pipe, Larry spent evenings sitting on the wraparound porch, enjoying the cross-breezes and the nearly 360-degree view of Camel’s Hump to the east and the Adirondacks to the west. The camp itself, which was built by the founder of the Laird-Shobert Shoe Company, was paneled with knotty pine on the inside and featured a large stone fireplace.

The Gardners loved to host big lobster bakes at the camp. Frequent guests included Burlington High School principal Dean Perreault, insurance agent Phillip Bell and Larry’s best friend, UVM track coach Archie Post. The Gardner boys also remember the time Larry’s old Red Sox teammate Dick Hoblitzell – and particularly his beautiful daughter – visited. From the camp the Gardners could watch fishermen netting sturgeon. When the south wind came up in early summer, Larry took his rowboat (equipped with a small motor) out to catch walleye and pike. His favorite spot for bass fishing was Hogback Reef, near the Colchester Lighthouse.

When the kids returned to school in the fall, the Gardners moved back to their comfortable brick cottage at 17 Overlake Park, in one of Burlington’s nicest neighborhoods. It was rented through the second week of September to two women who came down from Canada every summer to live near the lake. The living room was adorned with no pictures or trophies – they were all upstairs or down the basement. Larry told visitors he’d left his playing days behind and only took private trips back to the Boston, Philadelphia, and Cleveland of the early part of the century.

Still, he kept in touch with several old teammates, especially Harry Hooper. Larry also maintained a steady correspondence with Ty Cobb. In their playing days, he and Cobb were intense rivals. “I don’t think Ty ever bunted for a hit against me because I found out his secret early,” Larry said. “Cobb used to fake a lot of bunts, but I noticed that when he was really going to bunt, he always licked his lips. When I saw that, I’d start in with the pitch. He never realized I’d caught on.” In the 1950s Cobb wrote long, rambling letters to Gardner, trying to establish a fund for players whose careers had ended before major-league baseball’s pension system. In a letter dated September 17, 1958, Cobb wrote: “Nothing would please me more than to have a few days with you and your friends in your home town amongst those real people up there that I know of and their history so well, you being such a true representative. I should tell you now though you must have for years known it so well that I liked you also Ray [presumably Ray Collins], also your kind no matter where they lived, we were reared properly.”

Larry and Margaret Gardner enjoyed playing golf at Burlington Country Club. They didn’t keep score, even though Larry was very good. On Sundays Larry read the New York Times and listened to classical musical all day long. He also liked Bing Crosby, Perry Como, Joey Browne, and opera – Puccini was a favorite composer. “My God, listen to that,” he would say. “That’s a great tune!” On television Larry watched Perry Mason, Ed Sullivan, and Leonard Bernstein conducting symphonies. He was an avid reader, especially books about World War II. During the war he kept a map on which he pinpointed the advance of the Allied forces – a practice he discontinued when his son John was drafted.

Larry Gardner received numerous accolades as the years went on. Collegiate Baseball named him the third baseman on its all-time All-America team, and he was an original inductee into the University of Vermont’s Hall of Fame in 1969. In 1973, when SABR conducted a survey of its members to determine the greatest baseball player born in each state, Gardner was selected from Vermont. UVM’s most valuable player award in baseball was named after him, as was UVM’s cage (an honor he shared with Ray Collins). Still, the ultimate honor – induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame – eluded him.

“I remember when Harry Hooper was being considered for the honor and Dad talked with me after I raised the question about him being eligible for it,” said Larry Jr. “Generally speaking, Dad was very quiet, soft-spoken, reticent about his baseball career when talking with me, but at that one time he got very talkative – very adamant – and told me, ‘If you boys ever get involved with the campaigning, the politics of getting me into the Hall of Fame, I’ll be upset and angry.’”

William Lawrence Gardner died two months short of his 90th birthday on March 11, 1976, at Larry Jr.’s home in St. George, Vermont. He left his body to UVM’s Department of Anatomy, and his ashes were spread at St. Paul’s Cathedral in Burlington. Though he never was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, he continued to receive honors even after his death. In 1986 the UVM baseball team wore commemorative patches on their sleeves in honor of his 100th birthday. And when a regional chapter of SABR was founded in the Green Mountains in 1993, its members elected to call it the Larry Gardner Chapter. It was another fitting tribute to a Vermont baseball legend.

Sources

A version of this biography originally appeared in Green Mountain Boys of Summer: Vermonters in the Major Leagues 1882-1993, edited by Tom Simon (New England Press, 2000).

In researching this article, the author made use of the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the Tom Shea Collection, the archives at the University of Vermont, and several local newspapers.

Full Name

William Lawrence Gardner

Born

May 13, 1886 at Enosburg Falls, VT (USA)

Died

March 11, 1976 at St. George, VT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.