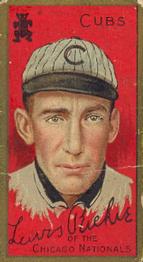

Lew Richie

Remembered for his dazzling performances against John McGraw’s Giants which earned him the nickname “Giant Killer,” Lew Richie’s eight-year career was spent entirely in the National League, where he quietly enjoyed a successful start with his hometown Phillies before emerging as a bona fide starting pitcher for Frank Chance’s powerhouse Cubs teams of the early 1910s.1 Despite a life filled with personal tragedy, Richie spent his years in baseball doubling as the team comedian and prankster, never taking anything too seriously and becoming known around the sport for his good-natured demeanor.2 Following his death in 1936, his obituary in The Philadelphia Inquirer read, “To the present generation of baseball followers, Lurid Lew was little known, but to the fans who followed the game a score or more years ago he was one of the outstanding pitching stars of the National League.”3

Remembered for his dazzling performances against John McGraw’s Giants which earned him the nickname “Giant Killer,” Lew Richie’s eight-year career was spent entirely in the National League, where he quietly enjoyed a successful start with his hometown Phillies before emerging as a bona fide starting pitcher for Frank Chance’s powerhouse Cubs teams of the early 1910s.1 Despite a life filled with personal tragedy, Richie spent his years in baseball doubling as the team comedian and prankster, never taking anything too seriously and becoming known around the sport for his good-natured demeanor.2 Following his death in 1936, his obituary in The Philadelphia Inquirer read, “To the present generation of baseball followers, Lurid Lew was little known, but to the fans who followed the game a score or more years ago he was one of the outstanding pitching stars of the National League.”3

Elwood Lewis Richie (Lew, as he would be known throughout his life) was born on August 23, 1883 in Ambler, Pennsylvania. He is still the only major-leaguer every to come from the small Pennsylvania town.4 His father, William Henry Richie, was a farm laborer from Philadelphia,5 and his mother, Anna Mary Richie (née Blake), was a laundress of English descent, born in rural Pennsylvania.6 Lew was the sixth of eight children in the household, preceded in birth by Laura (b. 1869), William (b. 1871), Anna (b. 1875), Bruce (b. 1876), and Maurice (b. 1879). His younger brother Frank was born in 1884 and younger sister Hester in 1889.7

As a teenager at the turn of the century, Lew earned pay as a laborer,8 and began the foundation for his baseball career on the “lots of the borough.”9 His first foray into organized baseball was with the Ambler Athletic Club in the Montgomery County League, which played its home games on ball grounds south of the Keasbey & Mattison Company asbestos plant, by the railroad. It was here that Richie thrust himself into the spotlight.10

In 1902, the 18-year-old struck out 111 men through his first eight games on the mound, leading Ambler A.C. to an undefeated season.11 “So great was the excitement every weekend when the team was to play, and it was known that Richie was to pitch, that the grounds would be lined with fans who came for miles.”12

Richie and his early-1900s Ambler club went up against some of the best teams in the tri-state area, often beating them handily. Once, he shut out the South Jersey League champions, 6-0. The visiting team’s management apparently did not accept the outcome, challenging Richie to a rematch at their site in Parkland the following week. He beat them again by the same score.13 Another time, he handed North Penn, which featured future Hall of Fame manager Joe McCarthy in the outfield, its first defeat.14

Though small in stature (5-feet-8 and 165 pounds), the right-hander soon outgrew Ambler. From 1903-1905, Richie bounced around various semipro and independent teams in the area, first with Doylestown15, then Wilmington. In 1904, he led the Oxford, Pennsylvania, team, then known as “one of the best in the country,”16 to a Chester County championship.17 He excelled at each stop.

Dave Landreth, who later served as a director for the Baltimore Terrapins in the Federal League, once told a story to reporters how around this time he hired Richie to pitch the morning game of a doubleheader in Bristol for the county championship for five dollars. Richie struck out 18 men and won, then came back and threw the second game for free because somebody had joked about him “winning the morning game on a fluke.” He won that game too. 18

By summer 1905, Richie was pitching in the independent minor Tri-State League for Williamsport, nicknamed the Millionaires because of the exceptional salaries they paid players.19 Richie, 21 at the time, won 26 of the 34 games he pitched for the Millionaires, including 14 in a row at one point.20 He also occasionally played right field, as he was a notable batsman.21

By August, Richie was pitching in the Class B Connecticut State League for the Holyoke Paperweights, and it was at this time, just before his 22nd birthday, that he began to be seriously pursued by major-league teams. 22 The first inquiry came from his hometown Philadelphia Athletics and manager Connie Mack. Mack was reported to have contacted the Holyoke manager and asked about a price for Richie, but a deal never came to fruition.23 Then, in late August, the Cubs purchased him, but the sale was “at variance with national agreement rulings” and fell through.24

Less than a month later, another legendary executive did pull the trigger on acquiring the young pitcher. Charles Ebbets, president of the Brooklyn Superbas, announced on September 17 that he had acquired Richie from Holyoke, along with the rights to dozens of other players from all around the country. Richie, clearly a headliner in the mass of transactions, was said to be reporting to the club in Boston the next day for their series against the Beaneaters.25 He never made it there. The sale was voided, and Richie was later deemed a free agent. 26

That offseason, an attorney named William S. Acuff helped Richie finally get his break. Acuff contacted management with the Philadelphia Phillies and convinced them to give Richie a tryout.27 The Phillies, like Mack’s Athletics, had been eagerly keeping tabs on Richie back in August when he was with Holyoke.28 However, the pitcher was caught up in another contract dispute, as he had signed on to play with Williamsport again in 1906 after the Brooklyn deal fell through.29 By April, the National Commission had sorted out the matter and declared Richie a free agent, leaving him free to sign with whichever team he pleased. Richie gave his hometown Phillies and club president Bill Shettsline the first call, to their delight, and on April 4 finally signed his first major league contract for $2,000.30 He was “practicing on the Athletic grounds prior to the game in the afternoon.”31

A report in the Ambler Gazette just after he signed with the Phillies described Richie’s pitching as “speedy and dependable,” and that he had a “speedy in-shoot, which fools the best batters” and his “drop ball is under as perfect control as his other curves.” He was said to hardly ever walk or hit batters.32

“Lurid Lew,” as he came to be known because of the thick, brightly-colored red sweater he wore under his short-sleeve jersey,” made his major league debut on May 8 against Boston at National League Park (later called Baker Bowl) in Philadelphia.33 He allowed four runs in five innings in relief and received a no-decision. His first win came on June 6 at home against the Reds — his first of two consecutive complete game shutouts in just his second and third career starts.

Richie spent his rookie season bouncing back and forth between the bullpen and rotation, making 22 starts and another 11 appearances in relief. In a bit of foreshadowing to his future claim to fame, he tossed complete games in his final two starts against the New York Giants, holding them to two runs in a 4-2 victory on August 31, and one run in a 3-1 win on October 3. They were the first of 14 complete games he would throw against the Giants in his career.

In 1907, Richie still served as swingman between the rotation and bullpen, but was used more often in relief roles, excelling, albeit in limited playing time. His 1.77 ERA was not only the lowest of his career, but ranked ninth among all pitchers with at least 100 innings in 1907. He became quite popular with the Philadelphia rooters and there was an even an eight-stanza poem written about him in the local paper in the exact style and rhyme scheme of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven.34

All of this success came in a year during which Richie suffered severe personal hardships. On January 9, 1907, his 17-year-old sister Hester died from tuberculosis. Three weeks later, his brother William, 35, succumbed to the disease. On March 29, it was older sister Anna, 31. It did not stop until it took half of the Richie siblings in the span of seven months. On August 1, his 30-year-old brother Bruce passed, leaving him with only two of his five older siblings and one of two younger still living.35

On the morning of August 1, Richie, with the Phillies in Cincinnati, received a telegram from home notifying him of his brother’s death. The team offered him an opportunity to take a train home that afternoon, but “loyalty to his club was too strong within him.” He did his part, holding the Reds to one run in a shortened six-inning game that the Phillies lost, 1-0, and then left for home.36 He met the team 10 days later in Chicago, tossing another six innings with just one run allowed.

Later that month, a potential trade threatened to take him away from his remaining family in Philadelphia. An August 28 report fueled whispers that Pirates manager Fred Clarke made Philadelphia an offer for Richie. It was bluntly said that “Richie is not to be long retained by the local club,” “things have not been breaking right for him here,” and that “there is no doubt Richie possesses the goods, but has not been able to deliver them for the Phillies.”37 The trade never materialized, and Richie did deliver the goods to end the season for the Phillies, throwing four straight complete games, two of which were shutouts, to end his year on a personal high note.

When March 1908 rolled around, Richie was not only still on the Phillies roster, but was making headlines across the country. The righthander, who pitched in the winter for Ormond in the Florida Hotel League,38 was granted permission to arrive late to spring training in Savannah as he was pitching in the championship down in Florida.39

When he arrived after the start of camp, Richie brought with him a new weapon — a pitch he “invented” in Florida.40 Reporters went crazy, dubbing it the “serpentine ball” because of its unique movement — the ball broke “several times before crossing the plate”41 — and was “the nearest thing to a snake on the grass ever invented.”42 He came to learn he could throw it only when he noticed his Florida catchers had trouble holding onto it (as did veterans Red Dooin and Fred Jacklitsch in Savannah).43

He unleashed the pitch on Phillies hitters in a March 11 intra-squad game first44, then struck out 10 members of the Savannah South Atlantic League team in an exhibition with it a few days later.45 Richie’s peers called it “the most remarkable ball yet introduced to the game by any twirler in the history of the sport,” and it was deemed a pitch “some crack players from the National and American League could not fathom.”46 Whatever the pitch was, it certainly didn’t hurt Richie to have in his repertoire.

Richie tossed three straight complete games — one of which went 10 innings — to start the season, and after the third was said to have been in “excellent form.”47 In another year with an undefined role (15 starts and 10 relief appearances), Richie went 7-10 with a 1.83 ERA.

When Richie signed his 1909 contract in February of that year, he boasted of being in “excellent shape, his health being better than it has been for several years” — but his opportunities became fewer and farther between.48 By July 14, he had appeared in only nine games, all in relief. The following day, he pitched an inning in the first game of a doubleheader against St. Louis, and then allowed three runs on 10 hits in eight innings in the second game.

The Phillies had seen enough. The next day, they shipped Richie, pitcher Buster Brown and infielder Dave Shean to the Boston Doves for outfielder Johnny Bates and infielder Charlie Starr. He finished out the season with a 2.32 ERA in 22 games (13 starts) for the Doves, but like in Philly, never fully settled into a role. The following May, less than a month into the season, he was traded again to the Chicago Cubs for outfielder Doc Miller.

In the Windy City, Richie’s career began to truly take flight. Two games into his Cubs career, it was said he “seemed like an entirely new pitcher just breaking into fast company,” and that “he will develop into one of Manager Chance’s best winning pitchers.”49 He did just that, going 11-4 for the remainder of the 1910 season.

One of his few missteps came in his first game back in Philadelphia on June 6. Frank Chance had Richie slated to start the game, but when the team went out for warm-ups he wasn’t there — he had gone back to Ambler to visit his family. Richie showed up just in time, received a warm welcome from the fans, and promptly gave up four runs in one and one-third innings. “Chance was probably wishing to thunder that Richie had stayed longer with his folks,” it said in the paper the next day.50

That year, the Cubs went back to the World Series for the fourth time in five years, and first since winning back-to-back titles in 1907-1908. They were no match for Mack’s Athletics, losing the Series in five games. Richie appeared in the only postseason game of his career in Game Two, tossing a scoreless inning in front of his hometown fans.

The 1911 season started on a sour note between Richie and Chance. Richie had been holding out on signing his contract, seeking an extra $600. Chance was so angry that he told Richie his contract would be decreased by $600, and the sum would be given to Jack Pfiester instead. When the club left for training in Louisville, Richie was not with them and it was not known whether he was coming. He eventually did arrive, paying his own train fare to do so.51 At the end of spring training, Chance nearly fined Richie another $600 for staying out all night, which he only found out about because he met him coming back to the hotel in the morning. An apologetic Richie was let off the hook, though, and bygones were bygones as the regular season started.52

From 1911-1912, Richie started 56 of his 65 games for the Cubs, going 31-19 with a 2.62 ERA, 33 complete games and eight shutouts. During those years he became known as the club comedian. Along with close friend Heinie Zimmerman, Richie kept the mood light with vaudeville acts, pranks and general silliness.53 A story on his retirement from baseball in the Winfield Courier, recalled “Lew was good for a laugh at any time. On the ball field or off, he had his fun, and he always kept the players in the best of humor.”54

He never took anything that happened on the field too seriously, often eliciting a laugh from players after getting knocked around by kicking himself and calling himself names as he left the field. One time, Chance asked him to warm up to enter a game, so he took a ball from his pocket, rolled it in his hand and said “Alright Frank, I’m ready,” drawing laughs from his teammates, but his manager’s ire, as he tended to do now and again.55

On the road, he and Zimmerman would sing and carry on for the team in the hotel lobby56 and play pranks on the train conductors between cities. “In ‘Lurid Lew’ Richie, the Cubs have a comedian par excellence,” one reporter wrote in 1912.57 However, it was another kind of joke that would make him famous in the sport and earn him a new moniker during his time in Chicago. “Comedian Lew Richie,” began a Buffalo Enquirer story from August 1912, “whose most famous joke is his record in defeating the Giants six out of seven games in 1911 and six out of seven in 1912 so far…”58

The New York Giants, who reached and lost the World Series each year from 1911-13, were the powerhouse of the National League. They featured Hall of Fame manager John McGraw and several pitchers, such as Christy Mathewson and Rube Marquard, who later would be enshrined in Cooperstown. Richie didn’t seem to mind.

Late in 1912, “The Giant Killer” defeated New York three times in one week, beating Marquard and Mathewson on August 15 and 17, tossing 11 innings in the latter game, and finishing the trifecta with a complete game shutout on August 21. After the third win, Richie joked, “I’m beginning to believe that licking the Giants is my personal prerogative. I think I’ll apply for privilege of pitching the entire Giants series in the East, entering the Polo Grounds in a blaze of glory and departing in a maze of militia, regulars and police to prevent any premature collection of insurance on my life.”59

From 1910-12, Richie started 19 games against the Giants, going 12-4 with 12 complete games and three shutouts, allowing two runs or fewer 11 times. The Cubs were 14-5 in those games. His starts against the Giants helped him in the wallet too — on Christmas Eve 1912, the club gave him a $1,000 check for winning 60 percent of his games that year (he went 16-8). It was actually a $500 offer, but the club doubled it since he missed the mark in 1911 by mere points (15-11, .577).60

That winter, Richie was down in Florida coaching at the Kentucky Military Institute.61 In late January, he was riding his motorcycle on the Daytona Beach automobile speedway and hit some sand, crashing at a high rate of speed. His bike was destroyed, and he was “badly cut, bruised and shaken up.”62 According to Chance, it was not the first incident with his bike — he and Zimmerman had been arrested once after losing control of a motorcycle, speeding down the street, blaming it on not knowing the controls and talking back to police.63

He reported to camp on time in 1913 and was with the Cubs as the start of the regular season, but he was never the same. Richie posted a 4.98 ERA through five starts and was relegated to a relief role, where he fared worse in 11 appearances, pitching to a 6.75 ERA. On August 9, the Cubs traded Richie to Kansas City in the American Association for pitcher Hippo Vaughn, who would win a pitching Triple Crown in 1918 and earn 151 victories over nine seasons with Chicago.

Richie pitched well enough in the final weeks of the season to earn a 1914 contract with the Blues, but got off to a bad start, and “failed to deliver the goods the way he should.”64 The Blues, “in desperate need for pitchers,” sold Richie to Sioux City in the Western League.65

A rejuvenated Richie went 9-1 with a 3.53 ERA in his 10 starts for Sioux City in 1914, helping them to a 105-60 record and the Western League pennant.66 Despite talk among ownership that Richie was “too high priced a man for the ‘stuff’ he handed out,” manager Josh Clarke offered him a contract for 1915.67 The veteran pitcher had other plans, however, and was said to have been close to signing on with a team in the Federal League when he was stricken with tuberculosis, the very disease that killed four of his siblings in 1907. 68

The reports, at first, were quite grim. One early headline read, “Lew Richie, Former Cub, Dying of White Plague.”69 Then, after it was later reported that doctors were “confident he would recover his health,” while resting at home in Williamsburg, it was intimated that his playing career certainly over.70

Richie had other ideas. He recovered from his spring scare, and by June was pitching for Chester in the Delaware County League in Pennsylvania, one county over from where he grew up.71 The competitive local league featured several former major-leaguers, and roughly half the players had minor-league experience.72 Seemingly fully recovered, Richie was even still throwing his famous “snake balls.”73 In late October, nine days after his former club, the Phillies, wrapped up their first World Series appearance, Richie was signed on to play an exhibition with other “All-Stars” in his old stomping grounds of Williamsport.74 It was quite possibly the final time he ever suited up for a game.

Richie moved around Pennsylvania in the latter half of the decade, working various jobs. When he registered for the World War I draft, he was living in Erie, and holding a job as a plumber for the Pennsylvania Railroad.75 At some point in the early 1920s, he moved back to Ambler. The disease that haunted him his whole life followed him there. The September 20 edition of the Ambler Gazette featured a story about the Montgomery County League “world series” between Ambler and nearby Perkasie. Mixed into the biggest local crowd in years at the grounds was Lew Richie and his mother, Anna. It was said he was “convalescing from a serious illness.”76 Richie said to his former manager William Urban that day, “It is like old times ‘Bill’ to hear this Ambler crowd root, and it has done me a world of good to be here.”77

The following year, still sick with tuberculosis, Richie was named manager of the Ambler Athletic Club team, the first team for which he ever played, by Urban, the very man who managed him as a young star in the early 1900s. At the helm of the club, Richie led Ambler to win the Montgomery County League pennant. Not long after, he fell more seriously ill. Through the help of a local politician in Germantown, he was admitted to the South Mountain Sanatorium, in South Mountain, Pennsylvania.78

He would never leave. Richie worked as an office clerk at the sanatorium while attempting to regain his health, but it progressively worsened from year to year.79 On August 15, 1936, just shy of his 53rd birthday, Richie passed away, becoming the fifth sibling in his family to succumb to tuberculosis. He was interred at Rose Hill Cemetery in Ambler alongside his brothers William and Bruce, sisters Anna and Hester, and his mother, who passed in 1931 from arteriosclerosis while he was at the sanatorium.80 Richie never married or had any children.81

A single line from a column published a year after his death summed up his life and playing career perfectly:

“Ritchie (sic) never took his failures very seriously, and he rated a good laugh as important as a strikeout with the bases loaded.”82

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Statistics were found primarily by Baseball Reference and Statspass. All Ambler Gazette archives were accessed through the online database of the Wissahickon Valley Public Library, and all other newspaper articles were accessed via Newspapers.com. A family lineage sheet created by Marty Richie, a relative of Lew and genealogical researcher, along with other email correspondence, was used for information on Richie’s siblings as well as his own marital status and profession while in the sanatorium. The information on that sheet that was used in this bio came from Pennsylvania death certificates, Findagrave.com and the 1930 U.S. Census.

Notes

1 Billy Evans, “Some Clubs Seem Helpless Before Certain Pitchers,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, January 27, 1918: 7.

2 “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 1937: 21.

3 “Lurid Lew Richie, Former Phil, Dies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 17, 1936: 16.

4 Players by Birthplace: Pennsylvania Baseball Stats and Info at https://www.baseball-reference.com/bio/PA_born.shtml, accessed March 20, 2021.

5 1900 US Census, accessed via Ancestry.com, March 30, 2021.

6 Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1968; Certificate Number Range: 074641-078390. File 7703A. Accessed via email correspondence with Marty Richie.

7 Family Group Sheet for William Henry Moore Richie, accessed via email message from Marty Richie to Kenny Ayres, March 24, 2021.

8 1900 US Census, accessed from Ancestry.com, March 30, 2021.

9 “Famous Big League Star Buried Here,” Ambler (Pennsylvania) Gazette, August 20, 1936: 1.

10 “Famous Big League Star Buried Here/”

11 Joseph Camburn, “Diamond Stars of 30 Years Ago,” Ambler Gazette, April 20, 1933: 1.

12 “Famous Big League Star Buried Here,” Ambler Gazette, August 20, 1936, 1.

13 “Famous Big League Star Buried Here.”

14 “McCarthy Paid $1 a Game and Glad to Get it.” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times Leader, October 8, 1929: 24.

15 “Town Topics,” Ambler Gazette, July 16, 1903: 5.

16 “Lurid Lew Richie,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 17, 1936: 21.

17 “Ambler Boy for Phillies,” Ambler Gazette, July 13, 1905: 1.

18 “Didn’t Win Game on Fluke.” Stevens Point (Wisconsin) Journal, April 8, 1915: 3.

19 “Lurid Lew Richie,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 17, 1936: 16.

20 Untitled, Winnipeg (Manitoba) Tribune, October 19, 1910: 6.

21 “Ambler Boy for Phillies,” Ambler Gazette, July 13, 1905: 1.

22 Charles F. Faber, Major League Careers Cut Short: Leading Players Gone By 30 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2011): 255-56.

23 “Chat of a Game Mostly on Meriden,” Meriden (Connecticut) Journal, August 5, 1905: 8.

24 “Dixon Returns Murphy Fight,” Meriden Journal, August 22, 1905: 8.

25 “New Players for Brooklyn.” Brooklyn Citizen, September 17, 1905: 5.

26 Faber, 256.

27 “Famous Big League Star Buried Here,” Ambler Gazette, August 20, 1936: 1.

28 “Must Report,” Rutland (Vermont) Herald, August 8, 1905: 2.

29 “Case of Pitcher Richie,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 7, 1906: 10.

30 “Ambler Boy for Phillies,” Ambler Gazette, July 13, 1905: 1.

31 “Another Shutout for the Phillies,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 5, 1906: 10.

32 “Ambler Boy for Phillies,” Ambler Gazette, July 13, 1905: 1.

33 “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 1937: 21.

34 Tom Waters, “The Slugger,” Ambler Gazette, May 23, 1907: 3.

35 Family Group Sheet for William Henry Moore Richie, per endnote 7, above.

36 Jack Ryder, “Blanks,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 2, 1907: 4.

37 “Pirates May Sign Richie,” Pittsburg Press, August 28, 1907: 8.

38 John Thorn email message to Kenny Ares, March 21, 2021.

39 “Tired Phillies Reach Savannah,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 6, 1908: 10.

40 “Phillies Wallop Honey Boys Again,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 13, 1908: 10.

41 “Phillies Wallop Honey Boys Again.”

42 “Skidoo Curve a Real Terror,” Pittsburg Press, March 12, 1908: 14.

43 “Phillies Wallop Honey Boys Again,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 13, 1908: 10.

44 “Skidoo Curve a Real Terror,” Pittsburg Press, March 12, 1908: 14.

45 “Phillies Win, But Oh What a Scare,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 15, 1908, 26.

46 “Phillies Wallop Honey Boys Again,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 13, 1908: 10.

47 “Lew Richie at Last Twirls a Winning Game,” (Camden, New Jersey) Morning Press, April 30, 1908: 3.

48 “Food for the Fans,” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, February 10, 1909: 12.

49 “Pitcher Richie is Making Good,” (Syracuse, New York) Post Standard, May 25, 1910: 11.

50 Jim Nasium, “Slam, Bang, Boom and it Was All Off,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 7, 1910: 10.

51 Home Run “Frank Chance Goes on Warpath; Calls Zim and Lew Richie,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, March 30, 1911: 4.

52 “Lew Richie, the Pitcher Who Nearly Lost $600,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 1, 1911: 3.

53 “Lew Richie, Comedian, Joined Cubs Last Night — Pitch Today,” Tampa Times, February 28, 1913: 11.

54 “Famous Player Through.” Winfield (Kansas) Courier, March 5, 1915: 6.

55 “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 1937: 21.

56 “Famous Player Through,” Winfield Courier, March 5, 1915: 6.

57 “A Big League Comedian,” Los Angeles Times, June 9, 1912: 118.

58 “Comedian Lew Richie,” Buffalo Enquirer, August 29, 1912: 9.

59 “‘Lurid Lew,’ Successor to Covaleski as Giant Killer,” Pittsburg Press, September 7, 1912: 8.

60 “Richie of Cubs Gets $1,000 Gift,” Bridgeport (Connecticut) Times and Evening Farmer, December 24, 1912: 7.

61 “Lew Richie, Comedian, Joined Cubs Last Night —Pitch Today,” Tampa Times, February 28, 1913: 11.

62 “Lew Richie Escapes Death in Accident,” Washington (DC) Times, January 21, 1913: 11.

63 Frank Chance, “There was Trouble Aplenty When Comedian Lew Richie Took Zimmerman for a Spin,” Fresno (California) Morning Republican, November 1, 1915: 8.

64 “Richie May Join Outlaw,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, December 18, 1913: 14.

65 “Famous Player Through,” Wichita (Kansas) Eagle, March 5, 1915: 8.

66 1914 Sioux City Indians stats at https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/stats/t-si14600/y-1914, accessed April 7, 2021.

67 “Richie May Join Outlaws,” Sioux City Journal, December 18, 1913: 14.

68 “Famous Player Through,” Wichita Eagle, March 5, 1915: 8.

69 “Lew Richie, Former Cub, Dying of White Plague,” Chicago Tribune, March 4, 1915: 11.

70 “Famous Player Through,” Wichita Eagle, March 15, 1915: 8.

71 “Media Shakes off Jinks by Defeating Chester,” Delaware County Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), June 21, 1915: 8.

72“A Review of D.C.L. Players,” Delaware County Times, June 18, 1915: 10.

73 Media Shakes off Jinks by Defeating Chester,” Delaware County Times, June 21, 1915: 8.

74 “Weldy Wyckoff Will Pitch for the All Star Professionals,” Williamsport (Pennsylvania) Sun Gazette, October 22, 1915: 2.

75 Lew Richie’s 1918 Draft Registration Card, accessed via Ancestry.com on April 10, 2021.

76 “First Victory Goes to Ambler,” Ambler Gazette, September 20, 1923.

77 “First Victory Goes to Ambler.”

78 “Famous Big League Star Buried Here,” Ambler Gazette, August 20, 1936: 1.

79 1930 US Census, accessed by email message from Marty Richie to Kenny Ayres, March 24, 2021.

80 Death Certificate for Anna Mary Richie, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Health Bureau of Vital Statistics, accessed via Ancestry.com on April 12, 2021.

81 1930 US Census.

82 “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 1937: 21.

Full Name

Elwood Lewis Richie

Born

August 23, 1883 at Ambler, PA (USA)

Died

August 15, 1936 at Franklin County, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.