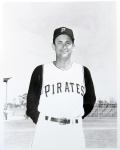

Mickey Vernon

In the 1940s and well into the 1950s, the premier first baseman in the American League was Mickey Vernon. On a daily basis, no other first sacker matched Vernon’s considerable ability as both a hitter and fielder. With a bat in his hands, Vernon’s classic left-handed stroke helped him win two batting titles, and he was regularly among the league leaders in a variety of offensive categories.

In the 1940s and well into the 1950s, the premier first baseman in the American League was Mickey Vernon. On a daily basis, no other first sacker matched Vernon’s considerable ability as both a hitter and fielder. With a bat in his hands, Vernon’s classic left-handed stroke helped him win two batting titles, and he was regularly among the league leaders in a variety of offensive categories.

Vernon was such an accomplished hitter that Satchel Paige, the ageless wonder, once said: “If I was pitching and it was the ninth inning and we had a two-run lead with the bases loaded and Mickey Vernon was up, I’d walk him and pitch to the next man.”

“I pitched him more carefully than anyone else,” pitcher Allie Reynolds claimed. “He’s not one of those powerful guys always looking down a pitcher’s throat, but he’s always ready. And he’s always guarding the dish. You pitch him outside, and he hits to left. You pitch him inside, and he can put it out of the park.”

Said pitcher Tom Ferrick: “Mickey was a very intelligent hitter with a good stroke. When Mickey went up to the plate, he knew who was pitching and how to handle the guy. He didn’t just go up and swing indiscriminately. He was the kind of guy who always put the ball in play. That’s why he got so many hits.”

Mickey was equally adept with the glove. Smooth, elegant, and graceful, he played first base as though he were performing an outdoor ballet. Few balls were hit his way that didn’t come to rest in his nearly flawless mitt. “He is the only man in baseball who could play first base in a tuxedo, appear perfectly comfortable, and never wrinkle his suit,” claimed Jack Dunn, an executive with the Baltimore Orioles.

To that, Ferrick added: “He was not only an excellent hitter and defensive player, he could steal bases. Mickey played the game the way it should be played.”

“I never patterned myself after anybody,” Vernon himself said. “(Playing first base) just happened to come naturally.”

Mickey was also durable. During his long career, he never missed much playing time because of injuries. His most serious injury came when he suffered a cracked rib when hit by a Tommy Byrne pitch in the last week of one season. Vernon is one of the few major leaguers who played in four decades, appearing from 1939 to 1960. He regularly played in 140 or more games a season, averaging 147 games per year between 1941 and 1955 and eight times performing in at least 150 games during an era of 154-game seasons.

As outstanding a player as he was, perhaps Vernon’s greatest attribute was as one of baseball’s finest gentlemen. He was an upstanding citizen, a family man, kind, courteous, caring, unbiased, one who was neither loud, profane, nor mired in his own ego. “He was,” said former New York sportswriter and baseball executive Arthur Richman, “one of the finest human beings I met in all my years in baseball. There was no one like Mickey Vernon. He shouldn’t even have been in baseball. He should’ve been in the White House.”

Added pitcher Mel Parnell, who played with Vernon on the Boston Red Sox: “I feel honored to have had him as a friend and a teammate. He is a wonderful individual who always commanded great respect in the clubhouse. I look back at him as being one of the best teammates I ever had.” Once, Vernon was driving through the city of Chester, Pennsylvania, and he saw a group of boys playing baseball with broken bats and beat-up old baseballs. Mickey drove home, rounded up some bats and balls, and returned to the field, where he gave the equipment to the surprised but grateful youths.

When Philadelphia Phillies broadcaster Harry Kalas, then a 10-year-old boy, attended his first big-league game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, he got a special tour that boyhood dreams are made on. Vernon saw him sitting in the stands before the game began. “He reached over and picked me up and took me into the dugout,” the Hall of Fame broadcaster recalled. “He gave me a ball and introduced me to some of the players. I was just in heaven. That started my love of the game of baseball.”

Once, during an interview, former pitcher and Vernon roommate Walt Masterson asked this writer if “anybody had said anything bad about Mickey?” Of course not, he was told. Why would anyone do something like that? “Well, if anybody does,’’ said Masterson, “you send him to me, and I’ll have a few choice words for him.”

Vernon played in all or parts of 20 big-league seasons. While most of his career was spent with the Washington Senators, Mickey also played with the Cleveland Indians, Red Sox, Milwaukee Braves, and Pittsburgh Pirates. Vernon’s best years were with Washington, where he appeared in 14 seasons. With the Senators, he won batting championships in 1946, with a .353 average, and in 1953, with a .337 mark. He beat out Ted Williams for his first title, and then edged Al Rosen by one point for the second one. Mickey is one of 22 American Leaguers who have won two or more batting crowns.

During a career that included seven other times in which he hit .290 or above, Vernon slammed 2,495 hits while compiling a career batting average of .286. He drove in 1,311 runs and scored 1,196 while playing in 2,409 big league games. In 8,731 at-bats in the majors, Vernon hit 490 doubles, 120 triples, and 172 home runs. His career high for hits in one season was 207 in 1946. In that season he led both major leagues with 51 doubles.

Although first base is a position usually manned by home-run sluggers, Vernon’s 172 homers were 101 less than the composite career average of the 17 major-league first basemen in the Hall of Fame. Vernon hit 15 or more homers in only four seasons. Nevertheless, Bob Feller called Vernon “one of the toughest batters [I] ever faced.” Mickey led the league in doubles three times (1946, 1953, and 1954), was second in total bases three times, and second in hits and triples twice each.

Mickey hit for the cycle on May 19, 1946, while facing the Chicago White Sox’ Eddie Lopat at Comiskey Park. He hit two grand slams (on August 13, 1955, at Fenway Park off the Red Sox’ Tom Hurd and on April 25, 1958, at Cleveland off the Detroit Tigers’ Jim Bunning). He hit four inside-the-park home runs and two pinch-hit homers.

He was a member of seven All-Star teams (1946, 1948, 1953, 1954, 1955, 1956, and 1958) and twice among the top five in the Most Valuable Player voting (1946 and 1953). Vernon had a career fielding percentage of .990. As of 2008 he held the major-league career record for first baseman for most double plays (2,044), and American League career marks at his position for most games played (2,227), most chances (21,467), most assists (1,444), and most double plays (2,041). He also participated in two triple plays as a fielder, one on September 14, 1941, against Detroit, and one on May 22, 1953, against the New York Yankees.

James Barton Vernon was born on April 22, 1918, at his parents’ home in Marcus Hook, a tiny borough that sits along the Delaware River in the southeastern part of Pennsylvania. He was the son of Clarence (known as Pinker) and Katherine, and had one sister, Edith, born seven years later. Pinker, a standout baseball player in local sandlot leagues, spent 43 years of his working career as a stillman and later as a jitney driver for Sun Oil Co. at its refinery in Marcus Hook. Katherine also worked briefly at Sun Oil before becoming a full-time housewife and mother.

By the time the boy was three years old, he had been given the nickname of Mickey. “There was a song called Mickey,” he recalled. “I used to play it over and over on the Victrola. My aunt Helen (Konegan) started calling me Mickey, and the name stuck. Soon everybody was calling me that.” Mickey attended Eddystone High School, where he was a basketball star. There was no baseball team at the school, so he played in youth leagues, including an American Legion team in nearby Chester. Although they had first met as opponents in a 12-year-old church basketball league, it was on that Legion team that Mickey became friendly with a Chester kid named Danny Murtaugh. The two became lifelong friends.

“In my first two years in Legion ball, I played right field because a bigger kid played first,” Vernon said. “I finally played first base my last year of Legion ball. There were only three positions a left-hander could play — the outfield, first, and pitcher — and I wanted to play every day, so first base appealed to me.”

As a teenager, Vernon hitchhiked to Philadelphia to see his favorite team, the Philadelphia Athletics, play at Shibe Park. In 1933, when he was in the 10th grade, he hitchhiked to Washington with three friends to see the Senators in the World Series. “I was crazy about baseball,” Vernon said. “I’ve been crazy about baseball as long as I can remember.”

Vernon was playing for Sun Oil in the Delaware Valley Industrial League when he accepted a baseball scholarship to Villanova University. At the time, Mickey also had a summer job at Sun Oil, walking a 3½-mile pipeline, looking for leaks. Mickey attended Villanova for one year, and played on the freshman team. After the season, he had an uneventful tryout with the Philadelphia Phillies. Then, at the urging of Villanova baseball coach George “Doc” Jacobs, who spent his summers as manager of the Easton (Maryland) Browns, a club in the Class D Eastern Shore League, Vernon worked out for the St. Louis Browns. The Browns signed him to his first contract, and in the spring of 1937, he headed to the minors.

Vernon hit .287 with 10 home runs in 83 games at Easton, which finished in second place. After the season, however, the Browns did not pick up his option, so he was signed by Washington super-scout Joe Cambria and became the property of the Senators. He spent spring training in 1938 with the Senators. “The thing I remember about that spring,” he said, “was that the Senators had about 12 or 14 Cuban players in camp. Gil Torres, who later played for the Senators, got them together, and they had a strike over meal money. It lasted a couple of days. I think they got maybe another 50 cents.”

Ultimately, Mickey was shipped to the Greenville (South Carolina) Spinners of the Class B South Atlantic League, where he hit .328 while playing in 132 games. The following year, he began the season with the Springfield (Massachusetts) Nationals of the Single-A Eastern League. After hitting a league-leading .343 in 69 games, the 21-year-old Vernon was called up to Washington. He made his big-league debut on July 8, 1939. He entered the first game of that day’s DH as a pinch runner in the ninth and scored a run. He started and went 1-for-5 in the second game with another run scored. He also helped turn the first of his 2,041 double plays. Vernon went on to hit .257 the rest of the season as the Senators’ starting first baseman.

At the start of the 1940 season, Vernon was sent down to the Jersey City Giants of what was then the Double-A International League. Called “Jimmy” by local sportswriters, the youngster hit .283 in 154 games. At the end of the season, he was summoned again to Washington, where he played in five games. He never played in the minor leagues again.

The year 1941 was a big one in Vernon’s life. On March 14, he married Elizabeth “Lib” Firth. He became the Senators’ regular first baseman, and hit .299 in his first full season. He followed that with .271 and .268 averages in the next two years.

Shortly after the 1943 season ended, Vernon was inducted into the Navy. He spent the next two years as a sailor, serving some of the time in Honolulu and the South Pacific, where he was part of a traveling baseball team, made up mostly of major leaguers, that played before crowds of 10,000 to 12,000 troops. At one point, Mickey also ran softball and basketball leagues. One of the players especially attracted his attention. He was a 20-year-old sailor named Larry Doby. The two became close friends, and later Mickey helped Doby became the American League’s first African American player. Vernon spent 1944 and 1945 in the service.

After his discharge, he returned home and began preparing for the start of the 1946 season. It was a special time in America, and baseball was no exception. All the big stars were back, and Americans, flocked to baseball parks in record numbers. In the American League, much of the attention focused on sluggers Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio, both back from the war after each had missed three full seasons. No one figured on Mickey Vernon, the quiet, slender first baseman of the Washington Senators, whose fondest memory from 1941 was hitchhiking with a friend to the World Series in Brooklyn from his home in Marcus Hook, and then standing all night in line at Ebbets Field to get center-field bleacher tickets.

When the 1946 season began, Vernon had yet to hit .300 in three years as a big-league regular. Having just returned from two years in the war himself, he hadn’t played at all in 1945 — not even service ball. But Vernon took the lead in the batting race early in the season, withstood a late challenge by Williams, and held on to capture the crown with a .353 average, 11 points higher than the Boston slugger, who finished second.

“I don’t know why I hit like that,” Vernon recalled. “The balls were just falling in for me. I remember at the All-Star Game that year, Bob Feller was talking to people about going on a barnstorming trip after the season. He asked me if I’d like to go, and I said, ‘Sure.’ He told me if I was still leading the league at the end of the season, he’d give me a bonus.”

Feller’s tour featured a team of major leaguers playing the best players from the Negro Leagues on a 40-game, cross-country jaunt. The major-league team included Vernon, as well as Stan Musial, Sam Chapman, Phil Rizzuto, Ken Keltner, Johnny Sain, Spud Chandler, and Dutch Leonard. “We played every night,” Vernon said. “Feller and Paige pitched the first three innings of every game. We played 11 doubleheaders. . . . We’d play Newark in the afternoon and Baltimore at night. Or New Haven in the afternoon and at Yankee Stadium at night.”

After his great 1946 season, Vernon’s average dropped significantly. He hit only .265 in 1947 and .242 the following year. Following the 1948 season he was traded to Cleveland along with pitcher Early Wynn for first baseman Eddie Robinson and pitchers Ed Klieman and Joe Haynes.

Although meeting Washington dignitaries was always one of the perks of playing with the normally downtrodden Senators, Vernon was still happy to leave Washington. “I was glad to get out of there,” he remembered. “I knew I was going to a pretty good club (which had won the World Series in 1948). But after I was there a while, they got Luke Easter to play first, and I was traded back to the Senators. Again, I was glad to be traded, but not back to Washington.”

Vernon’s average had bounced up to .291 in 1949, his first season with the Indians. On June 14, 1950, with Easter taking over as the Indians’ first baseman, Mickey went back to Washington, where he finished the season with a .281 batting average. He followed with .293 and .251 averages the next two years. During the 1952 season, Lib gave birth to the couple’s only child, Gay Anne. Much later, Gay became a prominent news director and host of an award-winning interview show at a radio station in Boston, a position she had held for some 30 years as of 2008.

In 1953, Mickey was back in the chase for the American League batting crown. Again he led most of the season, but had to go down to the last day to edge Al Rosen for the title by just one point with a .337 average. Vernon also drove in 115 runs and scored 101, making it the only season in his career that he broke the century mark in either category.

“Rosen got hot and really came on strong,” Vernon remembered of his race with the Cleveland Indians third baseman. “He had three hits the last day, and I had two. On his last at-bat, he was called out on a close play at first by Hank Soar. If he’d have gotten a hit there, he would have won the Triple Crown (Rosen led the AL with 43 home runs and 145 RBIs.)

“My guys didn’t want me to come up in the last inning,” added Vernon, who was due to bat fourth. “One guy got thrown out deliberately at second, and another guy let himself get picked off so I wouldn’t have to bat.” Vernon followed up his second batting title with .290 and .301 marks. In 1954, he hit a career-high 20 home runs.

After the 1955 season, the Senators again traded Vernon, this time to the Red Sox as part of a nine-player swap. Boston also received pitchers Bob Porterfield and Johnny Schmitz and outfielder Tom Umphlett, while the Senators got pitchers Dick Brodowski, Tony Clevenger, and Al Curtis, and outfielders Karl Olson and Neil Chrisley. With the trade, Vernon’s very special days in Washington came to an end.

Throughout his career, other teams were always pursuing Vernon. On numerous occasions, it was the Yankees. “When he was managing the Yankees, Bucky Harris once made a special trip during spring training from St. Petersburg to Orlando to get me,” Vernon recalled. “Clark Griffith (the Senators owner) said, ‘You’re not going to get him.’ Another time after I’d come back to Washington, I was walking out of the stadium, and Hank Greenberg, who was then the Indians’ general manager, drove by. He said, ‘I just made a good offer for you, and Griffith turned it down.’”

While he played in Washington, Vernon was only the third of three Senators first basemen who had covered the bag in a nearly unbroken string over four decades. Joe Judge manned the post from 1916 to 1930. Joe Kuhel was stationed at the initial sack from 1931 to 1937 and in the 1944-45 wartime years. Vernon made his debut late in 1939, and — except for 1940, when he was back in the minors, 1944-45 in the service, and 1949 and part of 1950 when he was with Cleveland — he occupied first for the Senators until 1955.

For much of the time, Mickey was not only one of the most popular players ever to pull on a Senators uniform; he was also the favorite of United States presidents, particularly Dwight Eisenhower. “One of my biggest thrills was on Opening Day one year [1954],” Vernon said. “I hit a home run in the 10th inning to beat Allie Reynolds and the New York Yankees. Right after I crossed home plate, some big guy — a Secret Service man, it turned out — came up and grabbed me by the arm and took me over to Eisenhower’s box. Ike wanted to congratulate me for hitting the home run.”

Mickey hit .310 and .241 in two seasons with Boston. In his first season, Vernon often batted fourth behind Ted Williams. “Pitchers would bear down on Ted, and have a tendency to let up on a fellow like me,” Mickey said. “This was to my advantage.”

Mickey hit .310 and .241 in two seasons with Boston. In his first season, Vernon often batted fourth behind Ted Williams. “Pitchers would bear down on Ted, and have a tendency to let up on a fellow like me,” Mickey said. “This was to my advantage.”

During the 1956 season, Vernon got stuck in an 0-for-28 slump. But he also beat the Yankees, 6-4, with a two-run homer in the seventh inning and bashed two doubles and a single in a 2-0 win over the Kansas City Athletics, and a two-run ninth inning homer to beat the Athletics, 3-2. He collected a home run, double, and single, and drove in four runs in a 9-3 win over the Tigers. The next day, he had five RBIs with a three-run homer and a single in an 8-6 victory over the Tigers. Over a 15-day stretch, Mickey had 15 RBIs with five home runs, five doubles, and five singles. At the end of the season, Vernon had 15 home runs and 84 RBIs.

In the early part of 1957, Vernon’s bat stayed hot. In one game, he collected four RBIs, three hits, and scored three runs in an 11-8 win over Detroit. His two-run homer in the eighth beat Baltimore, 5-4. Another two-run homer downed Kansas City, 3-2. And a two-pinch-hit home run with two outs in the bottom of the ninth beat the Yankees, 3-2.

Vernon’s bat cooled off as the season progressed, and he wound up splitting first base duties with Norm Zauchin and Dick Gernert. Mickey wound up playing in just 102 games. After the season, Vernon asked Boston general manager Joe Cronin if he thought Mickey should retire and take a coaching job he was offered. Cronin’s advice: “Don’t quit. You can still hit.”

That winter, however, Mickey was sold for $20,000 to the Indians. The Red Sox claimed that Vernon “couldn’t get the bat around anymore.”

In 1958, he hit .293 at Cleveland. The following spring, he was dealt to the Milwaukee Braves for pitcher Humberto Robinson. And Mickey’s long career in the American League was over.

In a reserve role in 1959 for Milwaukee, Mickey hit .220. At the end of the season, he was released. Shortly afterward, his friend Danny Murtaugh, the manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates, asked Mickey to become one of his coaches. Mickey signed on as the team’s first base coach. One of Vernon’s other jobs was to work with first baseman Dick Stuart and try to make him a better fielder, an extremely difficult assignment given the error-prone Dr. Strangeglove’s defensive shortcomings.

Late in the season, as the Pirates surged to the National League pennant, Vernon was activated as a player, appearing in nine games in September and collecting one hit in eight trips to the plate In the final at-bat of his career, Mickey grounded out in the 11th inning of a 4-3, 16-inning victory over the Cincinnati Reds.

Later, in one of the most riveting World Series in history, the Pirates met the Yankees. The Series went down to the final game with Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off homer in the bottom of the ninth inning at Forbes Field giving the Pirates a 10-9 victory and the world championship. “As the first base coach when Mazeroski hit the home run, I was the first person to shake his hand,” Vernon remembered. “When I saw the ball go out, I was just so charged up. That had to be one of my biggest thrills.”

“But just playing baseball was a thrill,” Vernon added. “I loved the game, and I’m very glad I played when I did and with the kinds of players I played with and against.”

After one year with the Pirates, Vernon became the first manager of the expansion Washington Senators, after the original Senators had become the Minnesota Twins. With a rag-tag band made up mostly of tired veterans and untried youngsters, the Senators posted a 61-100 record in 1961, tying for ninth place with the Kansas City Athletics. The Senators had last place all to themselves in 1962, finishing the season with a 60-101 record. Midway through the following season, with the team holding a 14-26 mark, Vernon was discharged from his duties as manager. The following season, Mickey returned to Pittsburgh, once again as a coach under Murtaugh.

After spending the 1965 season as a batting coach with the St. Louis Cardinals, Vernon embarked on a stint as a minor-league manager. Over a six-year period, he piloted the Vancouver Mounties of the Pacific Coast League for three years, the Richmond Braves of the International League for two, and the Manchester Yankees of the Eastern League for one. His best seasons were second- and third-place finishes with Vancouver.

After his stint in Manchester in 1971, Vernon returned to coaching. Over the next 14 years, he served as a minor-league hitting instructor with the Kansas City Royals, Los Angeles Dodgers, and the Yankees, and as the major-league batting coach with the Dodgers, Montreal Expos, and Yankees. In his final years in baseball, Vernon served as a scout with the Yankees, retiring in 1988 at the age of 70 after having spent 52 years in professional baseball.

Vernon is a member of another select group. He was pictured on baseball cards in four different decades. Mickey first appeared on a card in 1947 when his likeness joined the long and distinguished parade of Exhibit cards. With the exception of 1948, he was pictured either on Bowman or Topps cards every year from 1949 through 1963 and again in 1978.

Mickey and Lib lived for 52 years in Wallingford, Pennsylvania. Later, they resided near Media, Pennsylvania. Throughout those years, Vernon was a prominent member of the local community. He attended numerous events every year, a Little League was named after him, and a life-sized statue of him was placed in Marcus Hook. He also participated in numerous events for former major-league players that were held around the country.

“Mickey Vernon was the best first baseman in major-league baseball for most of the years of his long career,” said Feller when the statue was dedicated. “You were a great hitter, and a credit to baseball,” Musial added.

In his later years, Vernon was the recipient of numerous honors, including induction into the Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and Delaware County Halls of Fame. He has also been on the ballot for the Baseball Hall of Fame, the last time being as recently as 2008. Following a stroke, Vernon passed away on September 24, 2008, at age 90.

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Rich Westcott is the author of 19 books. All material above came from his book, Mickey Vernon, The Gentleman First Baseman (Philadelphia: Camino Books, 2005). Interviews for that book were conducted in person in 2003 and 2004.

Full Name

James Barton Vernon

Born

April 22, 1918 at Marcus Hook, PA (USA)

Died

September 24, 2008 at Media, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.