Patsy Tebeau

Patsy Tebeau was a pugnacious competitor from the mean streets of St. Louis who sought any advantage he thought he could gain. His tactics delivered a brand of baseball that clearly was much dirtier than you see in the modern game. Bill James has written about 19th century baseball: “The tactics of the eighties were aggressive; the tactics of the nineties were violent. The game of the eighties was crude; the game of the nineties was criminal. The baseball of the eighties had ugly elements; the game of the nineties was just ugly.”1 Tebeau, along with rivals Cap Anson and John McGraw, was a leader in 1890s baseball and helped cement the reputation of this era.

Patsy Tebeau was a pugnacious competitor from the mean streets of St. Louis who sought any advantage he thought he could gain. His tactics delivered a brand of baseball that clearly was much dirtier than you see in the modern game. Bill James has written about 19th century baseball: “The tactics of the eighties were aggressive; the tactics of the nineties were violent. The game of the eighties was crude; the game of the nineties was criminal. The baseball of the eighties had ugly elements; the game of the nineties was just ugly.”1 Tebeau, along with rivals Cap Anson and John McGraw, was a leader in 1890s baseball and helped cement the reputation of this era.

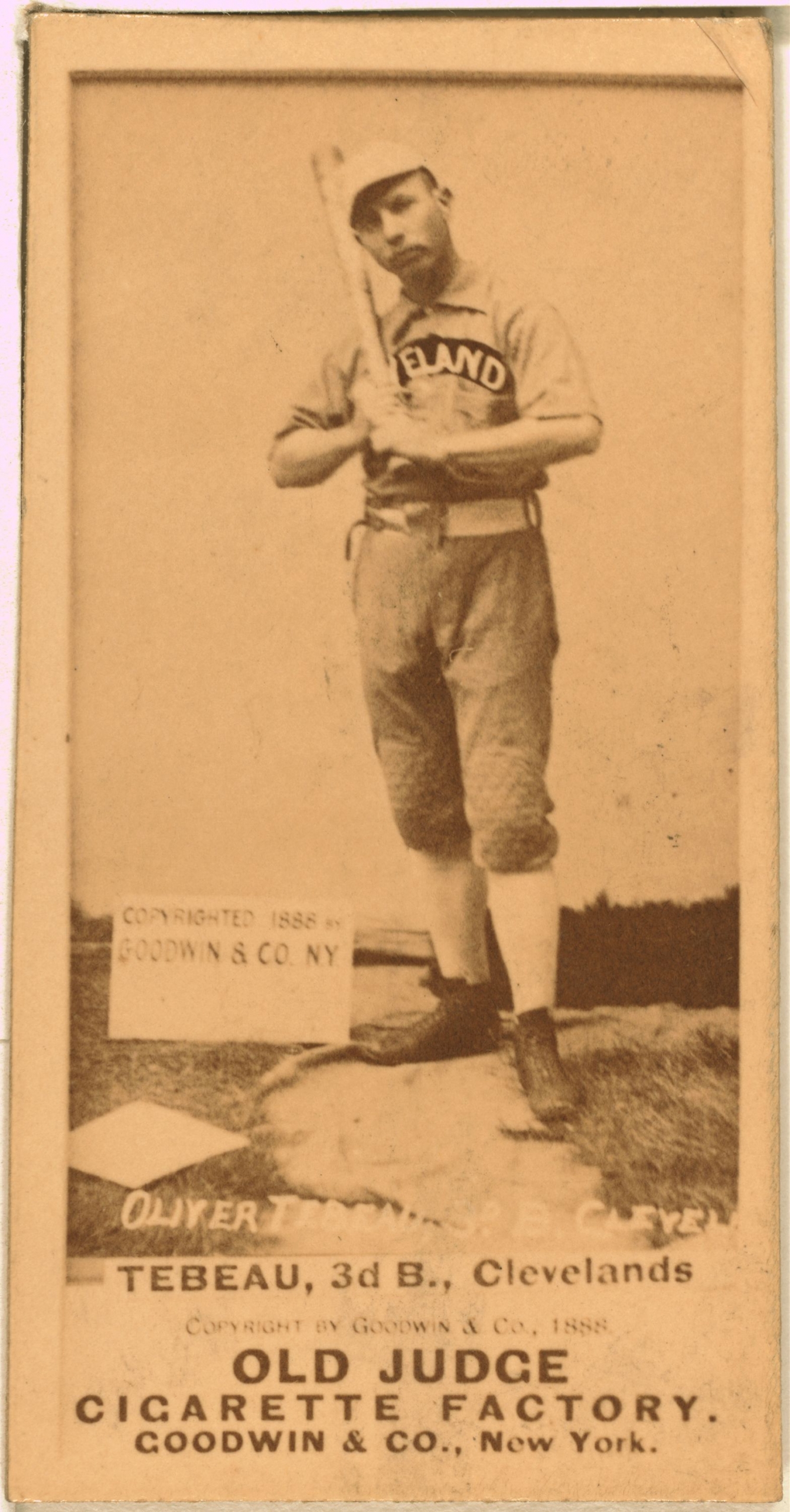

Oliver Wendell Tebeau was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on December 5, 1864, the youngest of the five surviving children of Louis and Louisa (nee Powry) Tebeau. Louis was a laborer with French-Canadian roots; Louisa was born in Maryland of German immigrant parents. Despite this background, they lived in the predominantly Irish Goose Hill neighborhood in north St. Louis. His brother George Tebeau played major league baseball but earned greater fame in the game as a minor league manager and owner.

Tebeau’s youth is not well documented. He most likely ended his formal education somewhere at the grade school level. By 1880 the 15-year-old was apprenticed to a file maker. There are different theories about Tebeau’s nickname, but the most likely is from a story he told later in life. As a youth, he took up with some Irish construction workers and began following them to their job site. He did odd jobs for them, including shoveling sand, and even bringing his lunch along. The workmen liked him, paid him a few pennies for his efforts and bestowed the Irish nickname ‘Pat’ or ‘Patsy’ on him. He also picked up an Irish accent from living in the neighborhood. The nickname and accent stuck.2

Tebeau gained local notice when he played on the Peach Pies, one of the top semipro teams in St. Louis. His teammates included catcher Jack O’Connor, pitcher Silver King, and his brother George. His professional career began on the independent Jacksonville, Illinois, team in 1885, where he caught the eye of Cap Anson as a prospect. In 1886, he joined the St. Joseph, Missouri, Reds of the Western League. The team was largely St. Louis natives and featured seven future major leaguers, including King and O’Connor. Their record was 50-30, finishing four games behind Denver.3 Tebeau frequently batted fourth in the lineup while playing third base, short stop, and second base. He hit .299 for the season.4 The local paper reported that Tebeau would be returning for the 1887 season.5

In January 1887 The Sporting News reported that Tebeau had signed to play for Denver’s Western League Club.6 Brother George played for Denver in 1887 but was signed to play for the major league American Association Cincinnati Red Stockings. Denver’s third baseman from 1886, Ira Phillips, had been badly frozen while on a hunting trip and the team needed an option if he did not recover.7 Tebeau was up for the challenge. On Opening Day, he was in the lineup at third base and went4-for-8 with a double while Denver crushed the Hastings (Nebraska) Hustlers in a football score, 37-12. His bat would not cool off. By mid-May, he was hitting .434, although his fielding average was .841. On June 4, he hammered a grand slam, fueling a comeback victory, and collected $37 in his cap from the crowd.8 Tebeau’s average stood at .424 with a slugging average of .550 in Colorado’s thin air.

The National League Chicago White Stockings, on Anson’s recommendation, purchased Tebeau from Denver for $1,000. The team was in a distant second place and decided to try out the young player.9. He was in the lineup for the first time on September 20 against Washington. The Chicago Tribune was optimistic, reporting, “Tebeau…acquitted himself very creditably. He handles himself in good style, and is a neat swift thrower, using his arm with a short twisting jerk.”10 Tebeau went 1-for-4 with a stolen base while committing one error at third in the Chicago win. Overall, his tryout was disappointing. During his 20 games, he hit .162, and had a fielding average of .855, both career worsts.

The White Stockings did not put Tebeau on their major league club for the 1888 season but did not release him, either. Eventually, the Western Association’s Minneapolis team secured his release after paying Chicago $1,500. “[Manager Gooding] is surely to be congratulated on securing Tebeau as he is undoubtedly as good a third baseman as there is in the National League,” enthused the Minneapolis Star Tribune.11 Tebeau was Minneapolis’ best player. He blasted two home runs in a July 19 game against Milwaukee and added another home run the next day. “Tebeau, as usual, covered himself in glory…” the scribes declared.12 He continued to produce, with another home run on July 28. He left the team two days later to go to St. Louis after being notified that his father was near death. While he was gone, the last-place team lost all but two games. After his father’s death, Tebeau returned to play on August 12. Minneapolis was insolvent, so they sold Tebeau to third-place Omaha on August 15. Fortified by Tebeau, Omaha ended the season in a second-place tie with Des Moines. In a post-season game to break the tie, Tebeau doubled but it was not enough as Des Moines won, 4-3.13

The Cleveland Spiders bought Tebeau from Omaha for the 1889 season and immediately put the 24-year-old to work. He played all 136 scheduled games at third and immediately showed off both his baseball knowledge and his competitive nature. He successfully executed two hidden ball tricks early in the season, one of which was the last out of a 5-4 victory. He drew a $10 fine for punching Phillies catcher Jack Clements after the Phillies third baseman tripped a Cleveland base runner, earning a $10 fine.14 However, Tebeau also employed these underhanded tactics, like shoving a runner off base and tagging him out when the umpire’s attention was elsewhere. Regardless of the legality, no less an authority than the New York Clipper praised “…the smart way Tebeau won a game for his club. Tebeau deliberately pushed the astonished Washington player off the base and held him there until Curry gave the out.”15 By the end of the season, he was a leader on the team and captain Jay Faatz’s primary lieutenant.16 He hit .282 on the season and led the team with eight home runs.

After the 1889 season, New York Giants shortstop John Montgomery Ward, president of the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players, announced the players would form their own major league circuit for the 1890 season. Tebeau and several of his Spider teammates jumped to the Cleveland entry in the new Players League. The team finished seventh; Tebeau hit .298 and tied for the team lead in home runs with five. On August 1, Cleveland fired player-manager Henry Larkin and named Tebeau to replace him. While the team was 21-30 under him, the local press blamed the talent, not him.17

Tebeau married Cleveland native Kate Manning on October 21, 1891, in Kansas City before a justice of the peace. In keeping with Tebeau’s adoption of Irish society, Kate’s parents were both Irish immigrants. The marriage was a hasty one as evidenced by the birth of their first child, Ruth Louisa, in February 1892. A second child, Oliver Howe, was born in 1899.

The Players League lasted one season. Most of the players who jumped to the new league returned to their former teams, and Tebeau was no exception. He returned to the Spiders but as a player only. Bob Leadley, the NL Cleveland Manager in 1890, retained his post. Writers of the day considered Tebeau a future manager as soon as the proper situation presented itself. The team had Cy Young, as staff ace, 20-year-old George Davis in center field and 23-year-old Cupid Childs at second. The core of a very good baseball team was in place. Unfortunately, Tebeau missed two months early in the year due to a severe spiking he received from Jake Beckley, who was known for his dirty play. Tebeau carried a lengthy grudge against him, admitting years later that he had been bothered by the injury for the rest of his career. The team played listlessly and hovered around .500 without him. When he returned on July 4, The Sporting News reported, “Captain Tebeau was royally welcomed. The crowd was glad to see him back and his coaching put a little extra life into the team.”18 Two weeks later, club owner Frank Robison fired Leadley and named Tebeau manager. The team played nine games under .500 for him, finishing fifth.

In an August 18 game against Cincinnati, an incident foreshadowed Cleveland’s future. The teams became involved in a brawl, initiated by Jimmy McAleer in the eighth inning. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, “[McAleer] in turning third, viciously kicked Arlie] Latham twice. Then Latham hit McAleer a hard punch on the jaw knocking him down.”19 After the game, Tebeau was not happy with Cy Young’s non-participation in the fighting and expressed his displeasure. He expected everyone to compete together.20

Tebeau was a smart and innovative leader. He was one of the first managers to take advantage of the new substitution rule and use pinch hitters. In one game late in the 1891 season, he used a pinch hitter against Chicago. Captain Cap Anson complained but Tebeau pulled a rulebook out and appealed to the umpire. The umpire ruled in Tebeau’s favor.21

Tebeau had learned his baseball by following the example Charles Comiskey had set in leading the St. Louis Browns to four consecutive American Association pennants in the 1880s. He believed fighting all the time was the way to play the game. Jesse Burkett, a future star, fit Tebeau’s ideal perfectly. He also filled his roster with role players such as fellow St. Louis native “Rowdy” Jack O’Connor, who would become Tebeau’s primary lieutenant. Like Comiskey, Tebeau built his team around pitching and defense and believed good tactics would take care of the offense.

The American Association folded after the 1891 season and four teams joined the National League. Tebeau completely overhauled the Cleveland pitching staff, releasing every pitcher but Cy Young (aside from one terrible start by Lee Viau) while adding George Davies from the defunct AA Milwaukee Brewers and, more importantly, Nig Cuppy, who would win 140 games for Cleveland during the decade. The 1892 pitching staff shaved off over one earned run per game from their 1891 total. Before the season, the National League set up a split-season schedule, with the first half and second half winners facing off in a post-season series.

Cleveland did not start well. Early in the season shortstop Ed McKean shot the end of his finger off in a clubhouse accident, missing several weeks. Young and Cuppy pitched well but needed help. Cleveland finished the first half of the season in fifth place in the new twelve-team league with a 40-33 record. But all teams started the second half, 0-0.

National League teams, understanding players had no negotiating power, started cutting payroll. The Boston Beaneaters, having won the first half race, cut veteran starter John Clarkson, who was suffering from arm woes, but Tebeau believed he had something left. So Cleveland club boss Robison signed Clarkson for the second half. The rejuvenated Clarkson pitched well in the second half, McKean healed from his injury, and the Spiders elevated their play. They won the second half by four games over the Beaneaters. This set up a best-of-nine series between the two teams.

The first game of the Series, in Cleveland, was a pitching masterpiece. Cy Young matched up with Jack Stivetts, both pitching eleven innings of shutout baseball until the game was called on account of darkness. This was the peak of the series for Cleveland; they dropped the next five contests, losing the series in a whitewash. Tebeau did not help, going 0-for-18. The Sporting Life was not kind, saying, “…this is the year he could not hit a balloon with a shotgun.”22 Tebeau hit .244 for the season and his fielding could best be described as steady. But no one questioned his managerial skills. “Tebeau is the youngest captain who has ever won a championship in the National League and is generally regarded among ballplayers as being one of the shrewdest men who ever stepped upon the diamond,” reported the Sporting Life.23

Baseball executives worried about the declining offense, so they made a major rule change for the 1893 season. The pitcher’s box was eliminated, and a rubber slab was put into place sixty feet, six inches away from home plate, moving the pitcher five feet farther away from the batter. The results were exactly what the baseball magnates wanted. Runs per game increased from 10.2 in 1892 to 13.2 in 1893. Coincidentally, the rowdy behavior, which had already been an issue in baseball, increased. Tebeau’s success with this style inspired more teams to copy these tactics.

Injuries were a big factor in Cleveland’s performance in 1893. Catcher Chief Zimmer suffered a broken collarbone against Boston in July in a collision at first base with Tommy Tucker. Middle infield stars Ed McKean and Cupid Childs both missed time with illness. Young, Cuppy, and Clarkson were still effective, but they all took a step back while adjusting to the new pitching distance. The Spiders finished third with a 73-55 record, 12 ½ games behind the Boston Beaneaters. Tebeau had the best playing season of his career, batting .329, well above the league average, while splitting time between first and third base with three games at second.

Cleveland’s and Tebeau’s negative reputations were cemented in their opponents’ minds. Many game reports noted Cleveland’s complaints against umpires and opposing players and reported on their aggressive, profanity-laced coaching. A particularly ugly incident happened against the New York Giants in the third game of an August series. Tebeau started complaining to umpire John Gaffney with the first pitch to the first batter. In the fourth inning, he came up to bat. After two called strikes, he started screaming expletives until Gaffney, with the help of local law enforcement, kicked him out of the game. The incident was reported on heavily and even Tebeau seemed repentant when he discussed it. But he also excused the behavior, “I am in favor of something that will put a stop to bad language on the field. But we are not the only offenders. I have heard the New Yorks say things in Cleveland that wouldn’t grace the columns of The Sun. And if we are worse than the Pittsburgs, then I’ll keel right over.”24

Before the 1894 season, Tebeau got into trouble. He and a friend went to a Cleveland brothel and ended up in a fist fight with the madam’s enforcers. He was arrested by police and paid a $250 fine to settle the incident. He later said the evening was his friend’s idea, but Tebeau was not above a night of drinking and intoxication likely played a role in the incident.25 Cleveland was involved in negative incidents from the start of the season, particularly with the Pittsburgh Pirates. During a May 12 game, Tebeau complained on every call made by umpire Jack McQuaid. The Spiders eventually lost the game, but their complaints made the game last a lengthy three hours, five minutes. Two weeks later, Cleveland fans stormed the field in the bottom of the ninth in another game against the Pirates. The umpire could not control the crowd and declared the game a forfeit, although the Spiders were down by nine runs and the loss was inevitable.

On June 1, the Spiders were in a three-way tie for first with Pittsburgh and Baltimore, a half-game ahead of Boston and Philadelphia. That was their high-water mark for the year. Tebeau signed older brother George to help the depleted outfield in the second half. George played well in his 40 games for Cleveland, but it was far from enough. The Spiders ended the season in sixth place, 21½ games behind Ned Hanlon’s Baltimore Orioles. Tebeau hit .302 on the year, but given high league batting averages, the mark was not impressive.

The 1895 season was Tebeau’s career high water mark. The Spiders, with Ewing and Clarkson gone, and a young Bobby Wallace as the third starting pitcher, were improved. They played their usual competitive ball, but Tebeau also used trickery. In an early season game, Chief Zimmer was hit by a pitch, but the umpire missed the play. Tebeau complained and surreptitiously pinched Zimmer’s arm during the argument, showing the new bruise to the umpire who awarded Zimmer first base.26 After a four-game sweep of the Baltimore Orioles by Cleveland in mid-July, the teams were tied for first place. The two teams battled the rest of the season, but Baltimore ended up three games better.

The two teams faced off for the Temple Cup in the postseason. Tebeau refused the Orioles’ offer to split the postseason money evenly because he wanted to win the championship. The first three games were in Cleveland and the Spiders fans were primarily a misbehaving force. They threw food at the Orioles, screamed at John McGraw, and used noisemakers to keep up a constant din. It worked, as Cleveland won all three games. When the teams moved to Baltimore, their fans responded in kind, attacking the Spiders as they stepped from their carriages at the ballpark. Baltimore won Game Four, but Tebeau was confident, with Cy Young pitching the next day. Young hurled a beauty, and Tebeau kept his temper, even after he was tagged in the face by John McGraw late in the game. Uncharacteristically, Patsy calmly walked off the field. Cleveland won the game, 5-2, and the series, 4-1. He also had his last decent offensive season, batting .318, but injuries limited him to 63 of his team’s 130 games. Now primarily a first baseman, his bat would not be a positive factor for the rest of his career.

The 1896 season was a near repeat of 1895. Baltimore won the pennant with a late-season rush, finishing 9½ games ahead of second-place Cleveland. Tebeau was as competitive as ever. In a June game, after he had hurled abuse at umpire Tom Lynch, Lynch challenged him to fight on the field in the middle of the game. Players and police kept the combatants apart. A week later, during a series with Louisville, umpire George Wiedman was physically abused and intimidated by Tebeau and his teammates after he called a game a tie due to darkness. Tebeau was fined by the local authorities $100 for assault and disorderly conduct.27 Two weeks later, the National League held a special meeting and fined him $200 for his behavior. Other incidents included destroying the clubhouse door in Brooklyn with his bat. He challenged both fines, eventually paying $10 to settle the assault charge and nothing to the league. The Temple Cup rematch was not competitive. Baltimore was highly motivated to show they were the better team and swept the Spiders. Tebeau hurt his back while batting in the second inning of the first game and did not appear again, managing from the bench while wearing a heavy coat to protect himself from the cold weather.

After the season, Tebeau committed one of his worst offenses, at least in the eyes of the media. He instigated a fight with a Cleveland reporter who had taken a negative view of his antics. Tebeau and O’Connor beat the reporter badly, but the man did not press charges. The Cleveland press, often supportive of Tebeau’s behavior, no longer backed him.28 Before the 1897 season, the National League instituted new rules designed to curb umpire abuse and general rowdiness, which seemed to dampen the fire from Tebeau and Cleveland. The team dropped to fifth-place and finished last in the league in attendance.

For the 1898 season, the league adopted the ‘Brush Rules,’ named after Cincinnati owner John Brush. These rules included guidelines to curb obscene language and a commission to review misbehavior and apply punishment. Other changes included the Chicago Cubs releasing noted umpire baiter Cap Anson and the 1897 victory of the clean-playing Boston Beaneaters over the rowdy Baltimore Orioles. The league also mandated the use of two umpires on the field in each game.

Tebeau was concerned enough about the Brush rules that he directed his players to work on controlling their language during spring practice. Cleveland started the season well. After their June 11th win, they were one game behind. But attendance was terrible and owner Robison started switching home games to opponents’ stadiums because he could earn more money with the visitor’s portion of the gate. The large number of road games wore down the team and they played much worse in the second half. Tebeau also felt the pressure. During a late July doubleheader in Baltimore, he threw a baseball bat at a heckler in the stands. No one was hurt but he was arrested after the game. He posted bail and left town with the team. The league did not punish him. Tebeau hit .258 for the season and the Spiders finished in fifth place again.

Due to poor attendance, Robison was in serious financial trouble. He needed to take drastic steps. The St. Louis Browns were for sale due to owner Chris Von der Ahe’s financial difficulties. Robison engineered a deal that netted him 51% of the team. As part of the deal, he moved all his best players to St. Louis while the leftovers went to Cleveland. Tebeau moved to St. Louis to become the player-manager of the new St. Louis Perfectos. Cy Young, Jesse Burkett, and Cupid Childs were among the players who also moved to St. Louis. The Perfectos improved from last place in 1898 to fifth in 1899 while the Cleveland leftovers had the worst season in baseball history, winning only 20 of their 154 games. Tebeau was only able to play half the season and he again hit well below league average.

The National League eliminated four teams before the 1900 season. Cleveland was one of the teams dropped, but Robison kept ownership of the St. Louis team, now called the Cardinals. Tebeau managed the team from the bench. He appeared in one game at shortstop in June, going 0-for-4 at the plate and committing three errors. According to the St. Louis Republic, Tebeau played the game using a first baseman’s mitt, and “the glove was scarcely big enough for Tebeau.”29 He resigned on August 19.

After his retirement from baseball, Tebeau focused on his saloon business with fellow St. Louis native ‘Scrappy’ Bill Joyce. In 1914, The Sporting News noted, “[Tebeau] has prospered and grown portly until Cleveland fans who had known him in the old days would hardly recognize him.”30 His downtown saloon was a popular place among baseball men, and he was known as a gentleman of integrity who would treat his old baseball enemies as friends.

However, by 1918 he was not a happy man. He suffered from rheumatism and some type of stomach trouble which made it difficult for him to move around. His wife left him and moved back to Cleveland in 1917. After a trip to French Lick, Indiana, he returned to his saloon in St. Louis despondent. In the early morning hours on May 16, 1918, he ended his own life in the back room of his saloon with a bullet from a revolver. In a suicide note, he wrote that his wife and brother George should be notified.31 His remains are buried in Calvary Cemetery in Cleveland, Ohio.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Baseball-Reference.com, Ancestry.com, and Newspapers.com.

Notes

1 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001), 52.

2 David L. Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017), 24.

3 “Sporting Events,” St. Joseph Gazette-Herald, September 21, 1886: 4.

4 “The Western League,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1886: 3.

5 “Diamond Chips,” St. Joseph Gazette-Herald, September 21, 1886: 4.

6 “Western League,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1887: 3.

7 “The Denver Club,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1887: 3.

8 “Showers of Silver,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1887: 6.

9 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Projiles, 1871-1900, Volume 2 (Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 409.

10 “A String of Big Naughts,” Chicago Tribune, September 21, 1887: 3.

11 “Signed Tebeau,” The Minneapolis Star Tribune, June 2, 1888: 3.

12 “Flour City Wins Again,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, July 20, 1888: 2.

13 “Western Association,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 18, 1888: 2.

14 Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 26-27.

15 “Baseball,” New York Clipper, August 3, 1889: 3.

16 “Baseball, National League,” Sporting Life, September 25, 1889: 2.

17 Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 40.

18 “Chips From Cleveland,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1891: 2.

19 “Fast and Furious,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 19, 1891: 2.

20 Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 53.

21 Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 52.

22 “Editorial Views, News, Comment,” Sporting Life, October 29, 1892: 2.

23 “A Young Napoleon,” Sporting Life, February 18, 1893: 1.

24 “Chadwick’s Chat,” Sporting Life, September 9, 1893: 3.

25 Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 89-90.

26 Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 101.

27 Fleitz, Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 123.

28 Rowdy Patsy Tebeau and the Cleveland Spiders, 132-133.

29 “Players Released by St. Louis Achieve Success,” St. Louis Republic, June 17, 1900: 17.

30 John H. Gruber, “Tebeau Hero of a Great Ball Team,” The Sporting News, February 19, 1914: 7.

31 “Pat Tebeau is Found Dead,” The Daily Times, Davenport, Iowa, May 16, 1918: 13.

Full Name

Oliver Wendell Tebeau

Born

December 5, 1864 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

May 16, 1918 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.