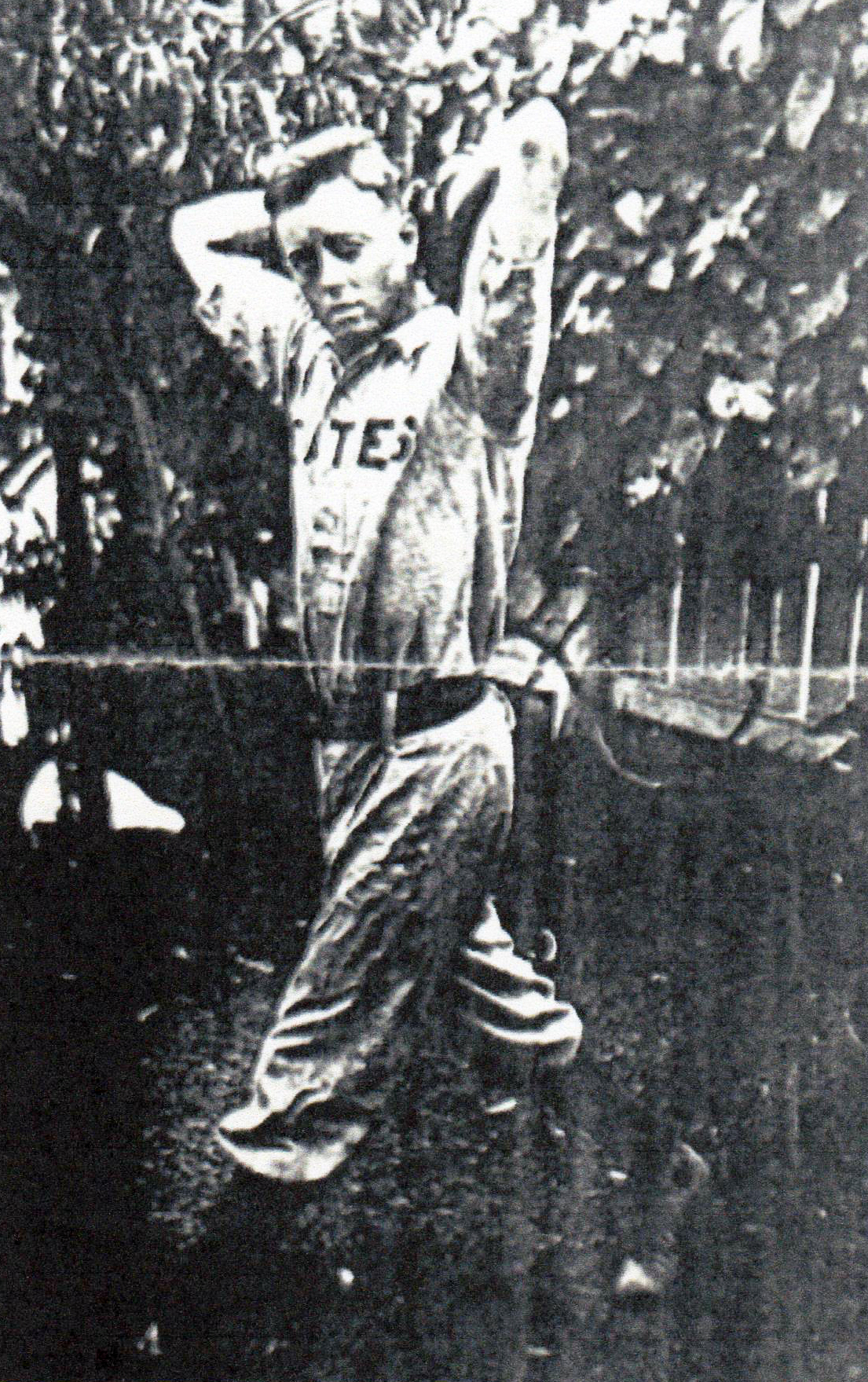

Roy Hoar

For the afternoon of July 29, 1914, baseball had two different John McGraws. In North Manhattan, the original John McGraw, the already renowned manager of the New York Giants, was orchestrating a 1-0 victory over the Pittsburgh Pirates at the Polo Grounds. For the time being, the win kept his three-times defending National League champion ballclub safely ensconced in first place. Meanwhile, some six miles to the southeast at Washington Park IV, an obscure namesake was summoned to pitch two innings of relief during the Brooklyn Tip-Tops’ marathon 18-inning 4-3 victory over the St. Louis Terriers. That Federal League outing marked the first and only big league appearance ever recorded by the right-hander identified by the press as John McGraw. Immediately thereafter, he disappeared from the professional baseball scene just as suddenly as he had arrived – this McGraw’s name never again appeared in a major or minor league box score.

For the afternoon of July 29, 1914, baseball had two different John McGraws. In North Manhattan, the original John McGraw, the already renowned manager of the New York Giants, was orchestrating a 1-0 victory over the Pittsburgh Pirates at the Polo Grounds. For the time being, the win kept his three-times defending National League champion ballclub safely ensconced in first place. Meanwhile, some six miles to the southeast at Washington Park IV, an obscure namesake was summoned to pitch two innings of relief during the Brooklyn Tip-Tops’ marathon 18-inning 4-3 victory over the St. Louis Terriers. That Federal League outing marked the first and only big league appearance ever recorded by the right-hander identified by the press as John McGraw. Immediately thereafter, he disappeared from the professional baseball scene just as suddenly as he had arrived – this McGraw’s name never again appeared in a major or minor league box score.

For more than 80 years thereafter, efforts to further research Tip-Tops pitcher McGraw were hampered by misapprehension of his identity. The confusion began early. Immediately following his July 1914 outing, the Brooklyn Times informed readers that “John McGraw of Louisville, Ky., no relation to John from across the river, … is a former college pitcher and has recently been playing with some of the semi-pro teams of the East. … His right name is R.E. Heir and he pitched for Carnegie Tech of Pittsburgh.”1 By 1969, however, the first edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia published by Macmillan was promulgating an alternate hypothesis, identifying our subject as James Leo “Jim” McGraw (1890-1918).2 This unsourced identification was thereafter adopted by ensuing baseball reference works through the initial edition of Total Baseball, released in 1989.

In 1995, some clarity regarding the true identity of pitcher McGraw was provided by two of SABR’s foremost baseball genealogists, the late Bill Haber and longtime Biographical Research Committee chairman Bill Carle. By means of government records and with input from the by-then deceased pitcher’s two sons, Haber and Carle concluded that McGraw was actually minor leaguer Roy Elmer Hoar, born December 8, 1890 in Intercourse, Pennsylvania; died, April 27, 1967 in Torrance, California.3 It was further revealed that Hoar sometimes used the surname Heir and that he had, in fact, pitched for Carnegie Tech.4 Sometime thereafter, Baseball-Reference added that this Hoar-Heir “played professionally under the name ‘John McGraw,’ after his hero, so as to not lose his amateur status while in college.”5

This profile will endeavor to expand upon the bare bones set forth above and provide a fuller account of the life and times of Roy Hoar, the Deadball Era’s other John McGraw. In the process, the writer will take issue with some of the currently proffered narrative about the pitcher, particularly the notion that Giants manager McGraw was a “hero” of Hoar or that he adopted the McGraw alias to protect his college athletic eligibility. Neither assertion is true. The reason why Roy was identified as John McGraw is unknown, as is the reason why he and his younger brother Clarence Victor Hoar, a two-sport college star and minor league pitcher, employed the surname Heir during their playing careers and thereafter. A baseball-centric profile of Roy Hoar aka John McGraw follows.

The Early Years

Roy Elmer Hoar was born on December 8, 1890 in Mount Nebo, Pennsylvania, a rural hamlet situated about 75 miles west of Philadelphia.6 He was the tenth of 12 children begat by farmer and blacksmith Theodore Eckert Hoar (1852-1922) and his wife Anna Marie (née Kling, 1854-1944), non-denominational Protestants of English and German descent, respectively.7 When Roy was still a boy, the Hoar family relocated, first to nearby West Lampeter, and thereafter to Lancaster, the county seat. An excellent student, he attended local public schools through graduation from Lancaster High School in June 1909.

Our subject’s baseball career traces to the sandlots of Lancaster where as young teenagers, he and Clarence played for a junior nine called the Invincibles.8 Subsequently, the 5-foot-9, 160-pound Roy starred on the baseball team (as pitcher) and football squad (as quarterback) at Lancaster High.9 Following receipt of his high school diploma, Hoar pitched several games for a fast amateur club 70 miles distant in Newport, Pennsylvania.10 Once he returned home, Roy did some postgraduate work (that mainly consisted of playing quarterback) at Yeates School, a Mennonite-run college prep located in Lancaster. He returned to area diamonds in spring 1910, alternating with Clarence between the mound and right field for the Monarchs, a top-notch amateur team.11

In late July, it was reported that “Roy Hoar, a well known local amateur pitcher will join the Huntingdon [Pennsylvania] independent team.”12 The following year, he entered the professional ranks, but news accounts conflicted regarding his club affiliation. First, it was announced that Hoar had signed with the Trenton (New Jersey) Tigers of the Class B Tri-State League.13 But before the 1911 season started, a hometown press report had “Roy Elmer Hoar, the crack local pitcher,” joining the Binghamton Bingos of the Class B New York State League.14 Upon arrival in Binghamton, he “did good work, but was inclined to be wild,” the Lancaster Morning News informed readers.15 In a preseason outing against the St. Louis Cardinals, “Hoar held the big leaguers down to two hits in the four [scoreless] innings he worked.”16 But after “he threw his arm out in practice games,” Roy drew his release from the Bingos.17 Before June was over, Hoar was back with the Huntingdon club.18

An all-around athlete, Hoar returned for the winter to Lancaster, where he teamed with his brother Clarence on an ice hockey team called the All-Collegians. In February 1912, the All-Collegians drubbed Yeates School, 21-5, with wingers Roy and Clarence Hoar each scoring five goals.19 Roy also played center for the All-Collegians basketball squad.20

By early April, Hoar was getting ready for another tryout in the New York State League, with press reports divided about equally on whether his audition was to be for the Scranton Miners or the Syracuse Stars.21 Whichever club it was, he failed to stick and spent the summer pitching for an amateur club near home in East Petersburg, Pennsylvania.22

In April 1913, the Pittsburgh Gazette-Times reported that the pitching prospects for Carnegie Tech included “Hoar, former pitcher for Franklin and Marshall College” in Lancaster.23 No evidence of Hoar actually pitching for F&M in 1912, however, was found by the writer.24 But newsprint and box scores plainly manifest that Roy Hoar pitched for Carnegie Tech of Pittsburgh during spring 1913, albeit only twice and without success. Although he performed well in both outings, Hoar lost 3-0 to Duquesne on April 1225 and dropped a 3-1 decision to Penn State on May 18.26

Thereafter, he took another stab at a professional career, signing with the Roanoke Tigers of the Class C Virginia League. Hoar “from Carnegie Tech” came “highly recommended by a scout of the St. Louis Nationals,” but was jettisoned the day after he failed to record an out in the third inning of his debut start.27 The quick dismissal perplexed the Roanoke Times, which remarked: “Manager [Buck] Pressley released Hoar after [a] two innings tryout. Who can tell what a pitcher has in two innings?”28

After spending time back in Lancaster, Hoar finally gained a foothold in Organized Baseball with the Poughkeepsie (New York) Honey Bugs of the lowly Class D New York-New Jersey League. Used as both a starter and in relief, he posted a respectable 9-7 (.563) record for a sub-.500 ballclub. He capped the campaign with a season-concluding complete-game 2-1 victory over the league champion Long Branch (New Jersey) Cubans.29 Along the way, two interesting events unfolded. First, for reasons undiscovered by the writer, Hoar was identified by the surname Heir while pitching for Poughkeepsie.30 More important, his performance attracted major league interest. Days after the NY-NJ League season ended, a Lancaster newspaper revealed that “Roy Hoar, who had a successful season with Poughkeepsie, … has been secured by Connie Mack,” manager/co-owner of the American League champion Philadelphia A’s.31 The acquisition of Hoar reportedly cost Mack around $5,000.32

In February 1914, Sporting Life announced that “Pitcher Roy Hoar [of Lancaster] will leave for Philadelphia this week to sign with the Athletics. Last year, Hoar was with Poughkeepsie of the New York and New Jersey League but was later secured by Troy [of the] New York State League. It was from Troy that Connie Mack secured him.”33 The Lancaster Morning News further related that “Hoar counts on going to Jacksonville, Fla…within several weeks when the advance guard of the White Elephants will go into training.”34

If Hoar actually got to spring camp with the A’s, he did not stay there long. For in mid-March, an official bulletin placed the contract of Roy E. Hoar with the Lowell (Massachusetts) Grays of the Class B New England League.35 Simultaneously, younger brother Clarence Hoar, then starring on both the diamond and the gridiron at Gettysburg College, was reported to be under contract with the Reading (Pennsylvania) Pretzels of the Tri-State League.36 Although the Lancaster Morning Journal subsequently reported that “Roy Hoar, the local pitcher, will sign with the Lowell, Mass., nine,”37 there is no evidence of record that he ever pitched for the Grays. Indeed, Hoar’s whereabouts and activities for the first half of the 1914 baseball season are presently unknown.

Enter Pitcher John McGraw

When and how Roy Hoar became a member of the Brooklyn Tip-Tops of the Federal League is a mystery. Also unknown is how and why the alias John McGraw became attached to him. Suffice it to say that nothing pertaining to these subjects was published in Brooklyn dailies prior to the start of the Tip-Tops’ home clash with the St. Louis Terriers on July 29, 1914. Taking the mound for Brooklyn that afternoon was rookie right-hander Dan Marion – who did not make it out of a two-run second inning. Reliever Byron Houck thereafter held the Terriers reasonably in check before he was removed for a seventh-inning pinch-hitter with Brooklyn trailing, 3-0.

The Tip-Tops had narrowed the deficit to 3-1 when an unknown righthander identified by the press as John McGraw took over hurling duty in the top of the eighth. The newcomer promptly got himself into trouble by hitting leadoff batter Ward Miller with a pitch. But a slick around-the-horn double play started by Brooklyn third baseman Tex Wisterzil emptied the sacks. McGraw then completed his maiden major league inning by striking out Hughie Miller.38

After a Steve Evans homer in the bottom of the eighth brought Brooklyn a run closer, McGraw returned to the slab for the ninth inning. He began smartly, striking out Al Boucher, but then walked Al Bridwell. As in the previous inning, the Brooklyn defense immediately came to the rescue, with catcher Grover Land converting a tapper in front of home plate into an inning-ending double play. With Brooklyn still trailing 3-2, McGraw was lifted in the bottom of the ninth for pinch-hitter Danny Murphy, who struck out. But singles by Claude Cooper and Art Griggs followed by a sacrifice fly to center by George Anderson knotted the score at 3-3.

Reliever John McGraw was long departed by the time that Brooklyn pushed over the winning run in the bottom of the 18th inning, the Tip-Tops’ 4-3 victory being the longest game played in the Federal League during the 1914 season.39 But his contribution to the triumph was duly noted in the press. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat declared that “John McGraw, a young namesake of Muggsy, the Giants’ boss, had the Terriers at his mercy in the eighth and ninth,”40 while the Brooklyn Daily Eagle stated: “This McGraw … He looks good.”41

Sparse press follow-up on the new Brooklyn pitcher was a mix of elements:

- Fact: “McGraw is a former college pitcher” and “pitched for Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh”;

- Fiction: “McGraw is a semi-pro pitcher from Louisville, Ky.” and “his right name is R.E. Heir”; and

- Possible but unverifiable: “he has recently been playing with some of the semi-pro teams in the East” and had “asked [Brooklyn manager Bill] Bradley for a chance.”42

Nor is the situation improved by our subject’s Baseball-Reference entry which states that Hoar “played professionally under the name ‘John McGraw,’ after his hero so as not to lose his amateur status while in college.”43 The historical record is devoid of proof supporting the claim that Hoar regarded John McGraw as a hero, while the assertion that Hoar was concerned about preserving his amateur status is belied by publication of the various news reports about “Roy Hoar” assaying a pro baseball career noted herein.44 Hoar had not used the McGraw alias previously, and if he wished to avoid scrutiny of his background, adopting an attention-gathering pseudonym hardly served that purpose. In sum, the reason why the Tip-Top’s new pitcher was identified as John McGraw is unknown and a head-scratcher.

Whatever his name origin and pedigree, new arrival McGraw’s major league debut pitching line – two hitless/scoreless innings that included inducing two double plays and notching two strikeouts – looks good on paper and seemed to warrant an encore. Yet Brooklyn never gave this McGraw another chance. His name entirely disappeared from Brooklyn box scores and newsprint for the remainder of the 1914 season. Finally, some seven weeks after his lone major league appearance, the Lancaster press announced that “Roy Hoar, who has been with the Brooklyn Feds, is back home in the city.”45

The Wind-Up of his Professional Career and the Post-Baseball Life of Roy Hoar

In January 1915, the Lancaster Morning News reported that “Roy E. Hoar, of South Lime Street, has gone to Brooklyn, and if satisfactory arrangements can be made with Walter Ward, [business] manager of the Brooklyn Federal team, he will sign with that team.”46 But nothing apparently came of the negotiations, and Hoar ended his professional career in the newly formed Colonial League, where he reassumed his Poughkeepsie alias, Roy Heir.47 He began the season with the Springfield (Massachusetts) Tips before being dealt in mid-July to a league rival, the New Haven (Connecticut) MaxFeds.48 He had little success with either club, finishing the campaign with a combined pitching record in the neighborhood of 1-10 (.091).49 As far as can be determined, this brought the professional baseball career of Roy Hoar, aka John McGraw, to a close.

Hoar had briefly attended Carnegie Tech, enrolled in the School of Applied Industries, but he did not graduate.50 At the time that he registered for WWI military service in June 1917, he was employed as a chemist for a rare metals product company located in Newark, New Jersey. In June 1920, he changed his domestic situation, taking 24-year-old Newark telephone operator Edwina Bullock as his bride.51 In time, the birth of sons Newland Dexter (1922) and William Blaine (1925) completed the family.

During the 1920s, Roy changed his residence, occupation, and surname, moving to Queens, becoming a hosiery salesman, and adopting his baseball alias Heir as his everyday surname (except when dealing with government agencies and representatives; for them, he remained Roy E. Hoar until 1960). Thereafter, he and brother Clarence, who had also begun using Heir as his last name,52 operated a mid-Manhattan importing firm called Heir Brothers, Inc.

Retiring from work around 1960, Roy and family moved cross-country, settling in the Los Angles enclave of Manhattan Beach, where he registered to vote as Roy E. Heir. Shortly thereafter, he developed arteriosclerosis and spent his final days in a Torrance, California, nursing home.53 Roy E. Heir (né Hoar) died on April 27, 1967.54 He was 76. Following funeral services, his remains were interred in Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California. Survivors included widow Edwina, sons Dexter and William, his sisters Carrie Sigman, Annabelle Hoar, and Minnie Hoar, and his brothers Clarence Heir, W. Blaine Hoar, and Miller Hoar.

More than 25 years after his passing, SABR researchers Bill Haber and Bill Carle discovered that one-game Brooklyn Tip-Tops pitcher John McGraw and marginal minor league hurler Roy Elmer Hoar (Heir) were one and the same person. This profile provides the first biographical portrait of this obscure Deadball Era dual personality.

The December 2024 SABR Biographical Research Committee Report adopted the recommendation that Roy Elmer Hoar be identified by his birth name. So, from now on, Roy Hoar will be known as Roy Hoar, not John McGraw.

Acknowledgments

This profile is adapted from an article published in the February 2025 issue of The Inside Game, the quarterly newsletter of the Deadball Era Committee. The assistance of Biographical Research Committee Chairman Bill Carle in the research process is much appreciated.

It was subsequently reviewed for the BioProject by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Photo credit: Roy Hoar, courtesy of William B. Heir.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info imparted herein are cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 “Brookfeds’ Notes,” Brooklyn Times, July 30, 1914: 4. Much of this misinformation was later placed on McGraw’s TSN player contract card.

2 This James Leo McGraw was later identified as an auto company machinist who died in Cleveland during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. See Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology: The Post-Baseball Lives and Deaths of Over 7,600 Major League Players and Others (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 264.

3 Haber and Carle Find Hoar,” Biographical Research Committee Report, March 1995: 1.

4 “Haber and Carle Find Hoar,” above, 1.

5 Baseball-Reference, John McGraw, (mcgrajo02), BR Bullpen: Biographical Information.

6 For years baseball reference works erroneously posited Hoar’s birthplace as Intercourse, Pennsylvania, a village located in Lancaster County. The December 2024 BRC Report corrected the Hoar birthplace to Mount Nebo.

7 Although residing in the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch country, the Hoars were not Amish or Mennonite. The family attended religious services at Faith Reformed Church in Lancaster.

8 As later noted in “City B.B. Pilot a Regular Fan,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Daily Intelligencer, March 7, 1917: 8.

9 In time, Clarence “Toppy” Hoar succeeded his older brother on the mound and in the backfield at LHS. In 1911, the younger Hoar led the Lancaster High football team to the Pennsylvania state championship, quarterbacking an undefeated eleven that outscored the opposition 272-0, per the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Sunday News, November 8, 1936: 12.

10 See “Personal,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Morning News, September 28, 1909: 1. See also, “State Capital,” Duncannon (Pennsylvania) Record, April 20, 1933: 8, and “Driftwood,” New Bloomfield (Pennsylvania) Times, April 20, 1933: 8, for reminiscences of the Newport manager on the club’s “pitching force” of Roy Hoar and others.

11 Although an exceptional athlete, the right-handed hitting Hoar was a surprisingly poor batsman and was only occasionally employed in the field when not pitching.

12 “Baseball Notes,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) New Era, July 23, 1910: 3. See also, “Notes of the Field,” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, July 23, 1910: 5.

13 See “Trenton Signs Lancaster Man,” Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, February 1, 1911: 11; “Sporting Notes,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Times, January 28, 1911: 8.

14 Personal,” Lancaster Morning News, April 13, 1911: 1.

15 “Twirling for Huntingdon,” Lancaster Morning News, June 24, 1911: 3.

16 Same as above. See also, “Base Ball Notes,” Lancaster New Era, June 24, 1911: 3.

17 As subsequently reported in “With Local Players,” Lancaster Morning News, April 4, 1912: 2.

18 “Twirling for Huntingdon,” and “Base Ball Notes,” above.

19 Per “All-Collegians Win at Hockey,” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, February 17, 1912: 8.

20 See “East Petersburg Won,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Morning Journal, April 13, 1912: 3; “Basket Ball at East Petersburg,” Lancaster New Era, April 11, 1912: 9.

21 For Scranton, see “Latest News by Telegraph Briefly Told,” Sporting Life, April 13, 1912: 3; “Flashes of the Diamond,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Morning Tribune, April 6, 1912: 10; “Scranton to Try Hoar,” Wilmington (Delaware) Evening Journal, April 5, 1912: 17; and “Hoar Goes to Scranton,” York (Pennsylvania) Dispatch, April 5, 1912: 16. For Syracuse, see “Will Be Given a Tryout,” Pittston (Pennsylvania) Gazette, April 10, 1912: 9; “Sport in Short,” Watertown (New York) Daily Times, April 8, 1912: 8; and “State League Notes,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record, April 6, 1912: 9.

22 See e.g., “East Petersburg 4, Lititz 3,” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, August 22, 1912: 6: “Hoar, a Lancaster boy, … allowed but five hits and struck out 14 men.”

23 “Baseball Outlook Is Bright at Tech,” Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, April 6, 1913: 18.

24 In April 1914, it was reported that Franklin & Marshall would host Gettysburg in the baseball season opener, and “no doubt Roy Hoar will be on the mound for the visitors.” See “F. & M. Will Open Ball Season This Afternoon,” Lancaster Morning News, April 30, 1914: 7. The Gettysburg pitcher was actually his brother Clarence Hoar, as even the hometown newspapers sometimes confused the two siblings.

25 As reported in “Carnegie Tech Is Handed Whitewash,” Pittsburgh Sunday Post, April 13, 1913: 35.

26 Per “Carnegie Tech Is Defeated by State College,” Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, May 18, 1913: 20.

27 See “Newport News Boys Trim Buck’s Tigers,” Roanoke (Virginia) Times, June 6, 1913: 6. The Newport News Shipbuilders scored six of their eight runs in the third inning of an 8-2 triumph over Roanoke.

28 “Baseball Briefs,” Roanoke Times, June 7, 1913: 6.

29 See “End Season with Double Victory,” Poughkeepsie (New York) Daily Eagle, September 8, 1913: 2.

30 Although unlikely the reason for the name change to Heir, same served to distinguish our subject from another NY-NJ League hurler, Herman “Beany” Hoar of the Kingston (New York) Colonials.

31 “Daily Chat about Amateurs,” Lancaster New Era, September 13, 1913: 6.

32 “Lancaster Boy Signed by Mack,” Lancaster Morning News, September 13, 1913: 3.

33 “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, February 7, 1914: 7, re-printing info previously published in the Lancaster Morning News. The New York-New Jersey League ceased operations at the close of the 1913 season and dispersal of its players to other circuits followed.

34 “Expects to Sign Up This Week,” Lancaster Morning News, February 2, 1914: 7.

35 “Latest Official Bulletin,” Sporting Life, March 14, 1914: 18.

36 Same as above.

37 “Sport Brief,” Lancaster Morning Journal, April 17, 1914: 6.

38 The above game account is drawn from the play-by-play published by Retrosheet.

39 The length of the contest necessitated the cancelation of the second game of a scheduled doubleheader.

40 “St. Louis Feds Lose Eighteen-Inning Game,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 30, 1914: 10.

41 “Brooklyn Feds Win in 18 Innings,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 30, 1914: 10.

42 “Brooklyn Feds Win,” above, and “Brookfeds’ Notes,” Brooklyn Times, July 30, 1914: 4.

43 Baseball-Reference, John McGraw (mcgraj02), BR Bullpen: Biographical Information.

44 Brother Clarence, a two-sport standout at Gettysburg College, also played professionally while in school without disguising his name. See e.g., “Hoar Signs with Newport,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 18, 1915: 12.

45 “Back from the Diamond,” Lancaster Daily Intelligencer, September 17, 1914: 3. See also, “Athletics,” Lancaster New Era, September 19, 1914: 7.

46 “Hoar May Join Federals,” Lancaster Morning News, January 14, 1915: 3. A nephew of principal club owner Robert B. Ward, Walter Ward was the Tip-Tops business manager.

47 See “Roy Heir Reports as Pony Pitcher,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, June 11, 1915: 17. Back in Pennsylvania, however, he remained Roy Hoar. See again, “Hoar Signs with Newport,” above: “Roy Hoar has been pitching for Springfield, Mass. … this year and has been making good.” The Colonial League was organized to serve as a farm system for the Federal League.

48 Per “Near Strike May Be Real Tomorrow,” Springfield Union, July 20, 1915: 10.

49 As calculated by the writer from Colonial League box and line scores published in the press. Baseball-Reference does not include Hoar’s Colonial League record in its entry for John McGraw, while the 1916 Reach Official Base Ball Guide provides only batting (1-for-20 = .050 BA) and fielding (.947 FA) stats in 11 games for Roy Heir.

50 Per November 14, 2024, email to the writer from Mary Weakland, Office of Enrollment Management, Carnegie Mellon University.

51 New York marriage records place the Hoar-Bullock wedding in Manhattan on June 30, 1920.

52 In 1978, the younger Hoar brother was posthumously inducted into the Gettysburg College Athletic Hall of Fame as Clarence V. Heir (Hoar). The older Hoar brothers (Clinton, Jacob, Milton, Willard, and C. Miller) retained the Hoar family surname their entire lives, and the reason why Roy and Clarence altered their last name was not uncovered.

53 According to the player questionnaire completed by his son William. Obituaries published back home in the Lancaster stated that Hoar died in his Manhattan Beach residence. See “Roy E. Hoar Dies in California,” Lancaster New Era, April 29, 1967: 3; “Roy E. Hoar,” Lancaster Intelligencer-Journal, April 29, 1967: 2.

54 State of California death records identify the deceased as Roy E. Heir, and that is the name inscribed on his tombstone. There is no indication in government records, however, that Roy ever legally changed his surname to Heir.

Full Name

Roy Elmer Hoar

Born

December 8, 1890 at Mount Nebo, PA (USA)

Died

April 27, 1967 at Torrance, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.