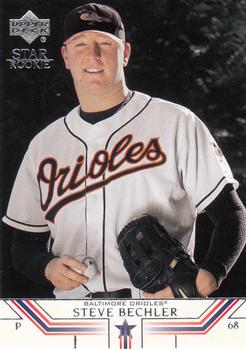

Steve Bechler

In September 2002, 22-year-old right-hander Steve Bechler debuted for the Baltimore Orioles and pitched in three games. In spring training the following February. he collapsed during a running exercise and died shortly thereafter. Weight-loss supplements containing ephedrine alkaloids were blamed for his sudden death. Their subsequent ban by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration became Bechler’s enduring legacy, while his baseball career will eternally raise the question, “What might have been?”

In September 2002, 22-year-old right-hander Steve Bechler debuted for the Baltimore Orioles and pitched in three games. In spring training the following February. he collapsed during a running exercise and died shortly thereafter. Weight-loss supplements containing ephedrine alkaloids were blamed for his sudden death. Their subsequent ban by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration became Bechler’s enduring legacy, while his baseball career will eternally raise the question, “What might have been?”

Steven Scott Bechler was born in Medford, Oregon, on November 18, 1979. His parents, California natives Ernie and Pat Bechler, had another son, Mike, in 1976, the year they were married. Ernie worked in a mill until a disability forced him to retire, while Pat spent nearly a quarter-century as a supervisor for Harry & David – the mail order supplier of premium gift baskets and fruit that is headquartered in Medford. Comice pears from the city’s Bear Creek Orchards are considered some of the world’s tastiest.

When Steve was a toddler, his 20-year-old half-brother, Ernie Jr., died from a brain aneurysm in Arizona. “He came in from playing baseball one day,” Ernie Sr. recalled. “He was hot, and he suddenly had a severe headache. He collapsed on the floor, and he was dead by the time the paramedics got there.”1 It would not be the last tragedy the family experienced related to baseball and heat.

As a boy, Steve was short, skinny, and reluctant to eat.2 He and Mike dreamed of meeting Rick Dempsey, the major-league catcher who entertained fans during rain delays with his pantomime routines. The brothers were competitive, and Steve gained valuable athletic experience through keeping pace with his older brother’s peers, who weren’t inclined to take it easy on him. Bechler learned his curveball from one of Mike’s friends.3

The Oakland Athletics had a Class A Northwest League affiliate in Medford, where future stars like Jason Giambi, Miguel Tejada, and Tim Hudson played their first minor-league ball. The Bechlers attended games but remained devoted Los Angeles Dodgers fans. L.A. won the 1988 World Series shortly before Steve turned nine. He liked pinch-hitting specialist Mickey Hatcher, but pitching ace Orel Hershiser was his main guy, and he told his brother earnestly, “I’m going to pitch in the big leagues.” Instead of kiddingly putting down his younger sibling as usual, Mike replied, “I believe you will, brother.” In 2022, he reflected, “It was the first time I believed in him, and he ran with it.”4

Rod Rumrey coached 10-year-old Steve in the Medford Little League. “He had a tremendous competitive attitude, and he was kind of a perfectionist,” Rumrey described. “And sometimes that would get the best of him. He might get mad and throw a little fit when he struck out, but he would always apologize and be so sincere with it.”5 Bechler remained intense as he advanced to Babe Ruth League and South Medford High School, where he also played basketball and quarterbacked the Panthers footballers. “He was a nice kid… and he was pretty emotional,” recalled South Medford athletic director Dennis Murphy. “He’d walk a kid, and all of a sudden he might lose it for the rest of the game. But as he got older, he no doubt got better with that.”6 Bechler’s brother taught him a phrase – “control the controllables” – that he inscribed on the underside of his hat.

As a junior, Bechler gave up basketball. He was named captain of the baseball squad and earned first-team All-Conference and honorable mention All-State honors in 1997.7 One particular performance caught the attention of professional scouts. In a matchup against Ashland High School senior Jeremy Guthrie – a future 13-season big-leaguer – Bechler won with a 17-strikeout one-hitter. “Who was that?” asked a Chicago Cubs scout afterwards.8

That summer, Bechler went 12-4 with a team-record 152 strikeouts in 124 innings for the Medford Mustangs in American Legion competition.9 “Steve wasn’t that much of a student,” recalled Mustangs coach Sandee Kensinger. “I think he knew what his ticket out was, and that summer really gave him some exposure.”10 The Mustangs reached the finals of the American Legion World Series (ALWS) in Rapid City, South Dakota. To win the championship, they needed to sweep a doubleheader against an opponent that hadn’t lost a single tournament contest – Sanford, Florida, led by Tim Raines Jr. Bechler won the opener, 12-2, and his coach recalled how the “half-kidding” pitcher “basically threatened me if he didn’t get to pitch the next game.” Medford was leading, 8-4, when Bechler was relieved in the fifth inning after throwing a total of 219 pitches that day around two rain delays. “He had what I called a gumby arm. He was durable,” Kensinger said.11

The game was televised on ESPN. As Bechler struck out the side in his final full inning, broadcaster Bob Boone – a former big-league catcher – marveled at his ability to extinguish threats with his curveball. “He’s done it consistently since four o’clock this afternoon, and it’s now 9:30,” remarked Boone. “Bechler came into this day known as a power pitcher. He’s going to go out known as a breaking ball pitcher.”12 Although Medford’s bullpen lost the lead and the championship, Bechler claimed the Bob Feller Pitching Award by leading all ALWS hurlers in strikeouts.13 Four of them came against Raines, though the Floridian also tagged him for two homers.14 For one year, Bechler’s Mustangs jersey was displayed at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Back home, Bechler worked as an assistant manager at Foot Locker.15 During his senior season at South Medford, he earned third-team All-Oregon recognition.16 John Gillette, a Baltimore Orioles scout for the northwestern United States, had noticed Bechler’s curveball and demeanor. “He was lanky as all get out,” said Gillette, estimating that the 6-foot-2 right-hander weighed 180 pounds at graduation. “He was a very confident, borderline-cocky, successful 18-year-old from a small town, a kid who dominated everybody he came in contact with, competitively.”17 Three days after Baltimore selected Bechler in the third round (99th overall) of the 1998 June amateur draft, he signed for a $257,000 bonus. “I wanted to get it done because I was so stressed,” he said. “The first thing I’m going to do is go buy a car and do something nice for my family.”18

Bechler reported to Sarasota, Florida to begin his professional career in the rookie-level Gulf Coast League. One of his teammates was Raines Jr., Baltimore’s sixth-round pick. The Orioles had Bechler’s parents flown in to witness his debut.19 In nine starts, he went 2-4, but his 2.72 ERA was nearly a full run better than the league average, and his 39:8 strikeout-to-walk ratio led the club.

Bechler spent 1999 with the worst team in the Single-A South Atlantic League and lost his first four decisions for the Delmarva (Maryland) Shorebirds 20 He wound up 8-12, including his first complete game as a professional, a one-hit shutout against the Macon Braves on July 26.21 With 26 starts, 139 strikeouts in 152 1/3 innings, and a 3.54 ERA, Bechler finished second on the team in each category to his roommate, fellow righty John Stephens.

The Orioles promoted Bechler to the Frederick (Maryland) Keys in 2000. Although manager Dave Machemer preferred to give him a less pressurized introduction to the High-A Carolina League, Bechler wound up starting and winning the home opener. After 17 outings, however, he was 3-9 (5.61 ERA) and on a six-game losing streak.22 Strong down the stretch, Bechler wound up with another 8-12 (4.83) mark. His 137 strikeouts tied for the Keys lead, and his 162 innings paced all Orioles minor-leaguers.

Bechler returned to Frederick as the Keys’ Opening Day starter in 2001.23 After an undefeated May, he struck out a season high 10 against the Lynchburg Hillcats on June 8.24 His fastball velocity was up to 95 mph.25 He was scheduled to fly to Lancaster, California, for the California/Carolina League All-Star Game on June 19 based on his 5-2 (2.27) record.

Two days before the game, Bechler was in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, with the Keys, preparing to head to the airport, when the Orioles called. Baltimore had just promoted Calvin Maduro from their Rochester Red Wings affiliate and wanted Bechler to start for that Triple-A International League club the following evening in Toledo, Ohio.26 Rather than change his plane ticket, however, Bechler had to ride 475 miles overnight by bus to Frederick, change his clothes and catch a noon flight out of Baltimore with a stopover in Pittsburgh. It all happened so fast that Bechler’s parents made the 12-hour drive to Lancaster in vain, unaware that his plans had changed.

“I was real nervous,” Bechler recalled. “I got to the hotel in Toledo at 5 p.m., to the field at 6 and the game was at 7.”27 He was clobbered for 11 runs in 2 1/3 innings, and said afterward, “I was getting dizzy. I had no sleep and nothing to eat. I was running on nothing but USAir pretzels.”28 Rochester manager Andy Etchebarren said, “It’s not fair. I’d like to see him get one more shot.”29

Five nights later, Bechler beat the Yankees’ Columbus farm club before he was reassigned to the Bowie (Maryland) Baysox, Baltimore’s Double-A Eastern League affiliate. Although Bechler was just 3-5 in 12 starts with Bowie, his ERA was 3.08 and he impressed pitching coach Tom Burgmeier as “a bulldog-type guy.”30 Between three levels in 2001, Bechler posted his first winning record as a professional (9-8) and struck out more than three times as many batters as he walked.

The Orioles added Bechler to their 40-man roster and sent him to the Arizona Fall League, a circuit for top prospects, to gain more experience. “The Orioles seem to have a lot of faith in their young pitchers,” he said. “That gives me a lot of determination.”31 Bechler went 0-5 (7.56) for the Maryvale Saguaros, however, having already pitched 169 2/3 innings that season before his arrival. “I was just tired,” he acknowledged.32

Baseball America rated Bechler as Baltimore’s 15th best prospect entering 2002. He attended major-league spring training for the first time and was able to pitch one exhibition inning against his “childhood idols” – the Dodgers. “I struck out Chad Kreuter. That was the highlight, he said. “I had to call my dad right afterward.”33 Bechler knew he had no chance to crack Baltimore’s Opening Day roster, but said, “I want to get in their minds.”34

Bechler returned to Bowie to begin the season, but a 2-1 (3.42) showing through four starts earned him a promotion to Rochester. In Triple-A, he lost his first six decisions with a 5.63 ERA.35 The extra pounds that the once-lanky Bechler had put on – by then he weighed well over 200 – caused as much or more concern than his record. “I talked to him many times about how he went about his job and how he needed to work a little harder to keep the weight off,” Etchebarren said.36

“[Bechler] had to be pushed. If he didn’t play baseball, he probably wouldn’t exercise ever,” observed pitcher Josh Towers, his roommate that season. The following year, Towers said that Bechler took supplements containing ephedra on the days that he pitched, explaining, “He liked the way he felt on it. I don’t think he took it to lose weight. I take it, too. It gives you a boost out there. And let’s be real – almost everybody in baseball takes something.”37 (In 2001, Bechler had reportedly told a liver specialist that he was taking ephedra.)38 As described by the Washington Post, “Although it is marketed primarily as a weight-loss aid, ephedra is a cousin of amphetamine and is often used by athletes to “get up” for a game.”39

Bechler went 6-5 with a 3.21 ERA in his last 15 starts for Rochester– including a nine-strikeout shutout of Scranton/Wilkes-Barre on July 21.40 Although he averaged 6.2 innings per start for the Red Wings, he would have worked deeper into games if not for the Baltimore organization’s pitch-count limits. Etchebarren opined that Bechler could develop into “a quality, 220- or 240-inning pitcher,” and said, “He never liked to come out of a game. He used to come into my office and ask if he could get the pitch count lifted.”41

At the conclusion of the Red Wings’ season, Bechler was called up to the majors. “He came in and thanked me and thanked [strength coach] Jay [Shiner] for taking the time with him to get him where he needed to get,” Etchebarren said. “He told me, ‘Etch, I’ve never felt this good. My arm feels great. My legs feel great.’”42

On September 6, 2002, Bechler made his big-league debut at Camden Yards, against the Anaheim Angels with 24,045 in attendance. His pregnant girlfriend, Kylie Nixon, played hooky from work to be there. When Bechler relieved Sean Douglass to begin the top of the sixth with Baltimore trailing, 4-3, Nixon recalled, “He looked like a kid in a candy store.”43 Over two scoreless innings, Bechler allowed three baserunners – on an infield hit, a hit batsman, and a base on balls. He was charged with one earned run after issuing another walk to the only hitter he faced in the eighth. “He came in and did a tremendous job,” said Orioles manager Mike Hargrove. “He showed a good fastball, a changeup and a breaking ball that he threw for strikes and got ahead of hitters.”44

“I’m just happy to get it over with. Hopefully, next time it will be better,” said Bechler.45 “It was a little tough. I’m not used to a lot of people. I was just trying to focus on the glove.”46 He made two more appearances in Baltimore. In a two-inning stint against the Toronto Blue Jays on September 19, he notched his first big-league strikeouts, against Josh Phelps and Orlando Hudson. But he also allowed solo homers to José Cruz Jr. and Shannon Stewart. Three days later against the Boston Red Sox, Bechler allowed a double and a pair of one-out walks to load the bases, then strained his right hamstring hustling to cover first base on a foul ball. Although he fanned Jason Varitek for the second out, he couldn’t push off the pitching rubber and Trot Nixon tagged him for a grand slam. After making one more pitch, Bechler departed, and his season was over. “I should have just said something instead of going out there and trying to be a tough guy and pitch,” he said. “You live and learn.”47

On October 22, 2002, Bechler and Nixon were married at Community Bible Church in Central Point, Oregon.48 They were expecting a daughter in April, and she recalled that, on the way home from the ultrasound, “He was already talking about what kind of car he was going to buy her and what a tough time he was going to give the first young man that came to pick her up.”49 They rented an apartment in Laurel, Maryland – a half-hour drive from Baltimore – so that Bechler could participate in the Orioles FanFest and offseason workouts. “You have this great opportunity. We have a young team, with spots open on the roster. We’re here for you. Let’s do this,” Orioles strength and conditioning coach Tim Bishop told him at the first session.50

Outfield prospect Larry Bigbie stayed with the Bechlers. Usually, he traveled to the ballpark alone because, he explained, he was the only one awake in time. When throwing sessions for Baltimore’s pitchers commenced in January, Bechler – unlike many of the guys he would be competing with – rarely stuck around to work out afterwards. Often, he didn’t show up at all. “I would call him up and say, ‘Dude, you can’t pull this crap… The coaching staff is there and they know who goes,’” recalled fellow prospect, Rick Bauer. “He just never dedicated himself. It just wasn’t his deal.”51

Kylie objected to characterizations of her husband as lazy. “Those practices were voluntary not mandatory,” she said. “I was pregnant. Every ultrasound, every time I had blood drawn, every time I had lab work, every time I had a doctor’s appointment, Steve was there. Those were morning appointments. He was where he should have been. He was with me. He wanted to be a dad, and that was way more important to him than baseball.”52

As the Orioles prepared to gather in Florida for spring training, Hargrove told the Baltimore Sun that Bechler could make the Orioles’ rotation.53 Despite lingering questions about the comebacks of veterans Pat Hentgen (elbow) and Scott Erickson (labrum) from surgeries, however, the same newspaper opined that Bechler was “likely headed to Triple-A Ottawa.” Mike Flanagan, the Orioles’ executive vice president, said, “You can make a case for guys to learn on the job here, but we don’t want to do that.”54

Bechler’s weight was 239 pounds according to the Orioles’ 2003 media guide.55 When he arrived for spring training in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, tipping the scales at 249 pounds, he heard about it from teammates and coaches. “If you don’t bust your butt in the offseason, guys don’t like that, because they’re all doing it,” Bauer said. “They think it shows lack of respect for the game.”56 On February 14, Bechler passed his routine physical.57 But after he was caught “cheating” during running drills the following day, he was pulled off the field and sent to the clubhouse. “I did it for disciplinary reasons,” Hargrove explained. “I told him that he had a wife and a baby coming in April, and that he chose this life as the way to take care of them, and it’s time he got serious about it.”58

Bechler’s friend, fellow pitcher Matt Riley, encouraged him in the clubhouse. “He was really distraught. I told him to keep his head up and keep working. He was like, ‘I messed up. I just want to change.’”59 The pair went out to dinner that night with Bauer, who recalled, “[Bechler] was feeling bad. I remember him saying, ‘I love this game, but I don’t want to die for it.’”60

The following morning, February 16, Bechler arrived shortly before the Orioles’ 9 a.m. workout. He hadn’t eaten breakfast, but he did take three Xenadrine RFA-1 pills – an over-the-counter weight-loss supplement containing ephedra.61 By 11:35 on the humid, 81-degree morning, a pale Bechler was back in the clubhouse, being treated for dehydration and heat exhaustion after he collapsed during a conditioning run. Less than 40 minutes later, he was on his way to the hospital in an ambulance.62 His body temperature had increased to 108 degrees. Riley took the Xenadrine bottle from Bechler’s locker and hurled it into a garbage can, though it was later retrieved for evidence.

When the Orioles called Kylie to tell her about her husband, she began the cross-country drive to be by his side.63 Near Salt Lake City, she received another call telling her to hurry and board a plane. She had asked Bechler to stop using ephedra multiple times.64 When the National Football League banned it the previous summer following the heatstroke fatality of 27-year-old Minnesota Vikings lineman Korey Stringer, the FDA had already linked it to more than 80 deaths.65 Ephedra was already prohibited by the NCAA and the International Olympic Committee.66

Along with Flanagan, Kylie maintained a bedside vigil as doctors kept treating Bechler, only to see one major organ after another fail. Bechler’s parents were riding to the hospital from the airport when he was pronounced dead at 10:10 a.m. on February 17.67 He was 23. Twenty minutes later, Hargrove called his players off the field and put his arm around Riley. Inside the clubhouse, Orioles GM Jim Beattie told the team.68

The Broward County medical examiner’s autopsy report mentioned Bechler’s borderline high blood pressure and liver abnormalities but implicated ephedra as the significant cause of death.69 Before February was over, Major League Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig banned ephedra throughout the minor leagues.70 Selig could not implement a similar prohibition in the majors, however, without the consent of the players’ union.71

In July, the Frederick Keys inaugurated the Steve Bechler Memorial Spirit Award.72 It was given annually to the player who best represented the spirit of Joel’s Kids, a group that aided children who were either seriously ill or dealing with the loss of a family member. That same month, Bechler’s widow filed a $600 million lawsuit against the manufacturer of Xenadrine RFA-1. (It was settled out of court in 2007.)73 Also, Bechler’s parents testified before Congress about the dangers of ephedra. Asked if his son’s death should be considered a cautionary tale, Ernie Bechler said, “That’s the only thing that me and my wife can hope for. The only thing.”74

On December 30, 2003, President George W. Bush’s administration announced its intention to eliminate ephedra-based weight-loss products from the marketplace. A new law went into effect on April 12, 2004, prohibiting the manufacture or sale of dietary supplements containing ephedrine alkaloids due to “unreasonable risk of illness or injury.”75 Following a legal challenge, the ruling was upheld by the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on August 17, 2006.76 “The number of poisonings resulting in major effects or deaths has decreased by more than 98% since 2002,” reported the New England Journal of Medicine nine years later. “The 2004 FDA ban has proved to be a very effective means of limiting the availability of ephedra and therefore its potential toxicity in the United States.”77

Nineteen days after Bechler’s death, a group of Orioles personnel traveled on club owner Peter Angelos’s private jet to join hundreds of mourners at a memorial inside South Medford High School’s gymnasium.78 Baltimore’s 2003 media guide contained these words next to Bechler’s biography: “Steve’s friendship was treasured by many for his sense of humor, his easy-going nature, and his positive outlook on life. Though he had not yet begun to leave his mark as a major league pitcher, he did leave it, more importantly, as a person.”79 Bechler’s daughter Hailie was born in April.

After the game at Camden Yards on August 17, eight Orioles players and staff accompanied Bechler’s widow as she spread his ashes on the pitcher’s mound and in both bullpens. “I think this is where he would want to be,” she said. “This is what he wanted. This was his life’s dream, and a good place to end it.”80

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mike Bechler (telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, January 20, 2022).

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Russ Walsh.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.baseball-reference.com

Notes

1 “Family: Pitcher Had Heatstroke While in High School,” ESPN.com, February 19, 2003, https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/2003/0219/1511221.html (last accessed January 20, 2022).

2 Joe Christensen, “Parents: Bechler Had Problems with Heat,” Baltimore Sun, February 19, 2003: 1D.

3 Mike Bechler, Telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, January 20, 2022. (Hereafter, Bechler-Allen interview)

4 Bechler-Allen interview.

5 Don Hunt, “A Born Competitor,” Mail Tribune (Medford, Oregon), February 18, 2003, https://www.mailtribune.com/business/2003/02/18/a-born-competitor/

6 “A Battler Who Blossomed On, Off Field,” Washington (DC) Times, February 18, 2003, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2003/feb/18/20030218-085556-2196r/ (last accessed January 20, 2022).

7 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 44.

8 Bechler-Allen interview.

9 Hunt, “A Born Competitor.”

10 “A Battler Who Blossomed On, Off Field.”

11 “A Battler Who Blossomed On, Off Field.”

12 “Chaz Lytle: American Legion World Series 1997, 2,” Chaz Lytle YouTube channel, January 14, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ca_GvztmzBo (last accessed January 22, 2022).

13 “Bob Feller Pitching Award,” https://www.legion.org/baseball/awards/pitching (last accessed January 20, 2022).

14 David Preszler, “Orioles Give Bechler Signing Bonus of $257,000,” Mail Tribune, June 10, 1998.

15 Steve Bechler, 1999 Multi-Add SAL Top Prospects baseball card

16 Greg Stile, “Rumrey Named 4A Baseball Player of Year,” Mail Tribune, June 17, 1998.

17 Dave Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work,” Washington Post, March 11, 2003: A1.

18 Preszler, “Orioles Give Bechler Signing Bonus of $257,000.”

19 Preszler, “Orioles Give Bechler Signing Bonus of $257,000.”

20 “Cats’ Dismal Road Trip Ends,” Charleston (West Virginia) Gazette, May 13, 1999: 4B.

21 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 44.

22 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 44.

23 Kent Baker, “New Owner Brings New Ideas for O’s Affiliates,” Baltimore Sun, April 5, 2001: 3D.

24 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 44.

25 Steve Bechler, 2002 Bowman baseball card.

26 “Toledo Crushes Wings, 18-5,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), June 19, 2001: 45.

27 Kent Baker, “Road to Triple-A Not Easy for Bechler,” Baltimore Sun, July 16, 2001: 3D.

28 Jim Mandelaro, “Red Wings Notebook,” Democrat and Chronicle, July 7, 2001: D5.

29 “Toledo Crushes Wings, 18-5,” Democrat and Chronicle, June 19, 2001: 45.

30 Baker, “Road to Triple-A Not Easy for Bechler.”

31 Baker, “Road to Triple-A Not Easy for Bechler.”

32 Roch Kubatko, “If Given the Choice, Groom Would Prefer Role as Set-up Man,” Baltimore Sun, February 17, 2002: 6D.

33 William Gildea, “That Was His One Dream, to Play Major League Baseball,” Washington Post, February 18, 2003: D1.

34 Kubatko, “If Given the Choice, Groom Would Prefer Role as Set-up Man.”

35 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 43.

36 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

37 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

38 Joe Christensen, “Examiner Points to Ephedrine in Bechler’s Death,” Baltimore Sun, February 26, 2003: 1D.

39 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

40 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 43.

41 Roch Kubatko, “On Field, O’s Try to Get Back in Game,” Baltimore Sun, February 19, 2003: 1D.

42Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

43 Peter Schmuck, “Bechler Receives One Last Ovation,” Baltimore Sun, March 9, 2003: 1E.

44 Dan Connolly, “Angels Dispose of Orioles’ Youngsters,” Baltimore Sun, September 7, 2002: B1.

45 Kathy Orton, “Two O’s Struggle to Make Pitches,” Washington Post, September 7, 2002: D7.

46 Roch Kubatko, “Angels, Fatigue Do in Orioles, 6-3,” Baltimore Sun, September 7, 2002: 1C.

47 Roch Kubatko, “Pitching in Pain, Bechler Hurt by Slam, Too,” Baltimore Sun, September 23, 2002: 6C.

48 “Steven Scott Becker,” Mail Tribune, February 28, 2003.

49 Schmuck, “Bechler Receives One Last Ovation.”

50 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

51 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

52 Joe Christensen, “Bechler’s Words, Life Resonate with His Wife,” Baltimore Sun, July 13, 2003: 1E.

53 Roch Kubatko, “Roster Iffy, Hargrove Still Delivers Optimism,” Baltimore Sun, February 2, 2003: 3E.

54 Joe Christensen, “O’s Pitches Arm-Wrestle for Five Spots,” Baltimore Sun, February 14, 2003: 1D.

55 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 44.

56 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

57 Christensen, “Examiner Points to Ephedrine in Bechler’s Death.”

58 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

59 Kubatko, “On Field, O’s Try to Get Back in Game.”

60 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

61 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

62 Roch Kubatko, “Bechler Being Treated for Heat Exhaustion,” Baltimore Sun, February 17, 2003: 10D.

63 Dan Connolly, “Steve Bechler’s Death Five Years Later,” Baltimore Sun, February 17, 2008: D1.

64 Sheinlin, “It’s No Substitute for Hard Work.”

65 Associated Press, “NFL Bans Herbal Ephedra,” New York Times, September 9, 2001: C8.

66 Scott Blair, “NCAA Ephedra Ban Raises Athlete Issues,” Daily Bruin (University of California, Los Angeles), February 4, 2002, https://dailybruin.com/2002/02/04/ncaa-ephedra-ban-raises-athlet (last accessed January 24, 2002).

67 Joe Christensen, “Parents: Bechler Had Problems with Heat,” Baltimore Sun, February 19, 2003: 1D.

68 Christensen, “Parents: Bechler Had Problems with Heat.”

69 Connolly, “Steve Bechler’s Death Five Years Later.”

70 “Baseball Bans Ephedra for Minor Leaguers,” Toronto Star, February 28, 2003: C3.

71 Jonathan D. Salant, “Union: Full Ban or No Ban on Ephedra,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 25, 2003: B5.

72 “Huggins Given Inaugural Steve Bechler Memorial Spirit Award,” Our Sports Central, July 17, 2003, https://www.oursportscentral.com/services/releases/huggins-given-inaugural-steve-bechler-memorial-spirit-award/n-2336482 (last accessed January 24, 2022).

73 Connolly, “Steve Bechler’s Death Five Years Later.”

74 Peter Schmuck, “For O’s, Bushes Message is Clear,” Baltimore Sun, January 22, 2004: 1E.

75 Patricia Hagen, “Forbidden Substance,” Indianapolis Star, March 12, 2004: E1.

76 Lesley Mitchell, “Ruling Upholds Ban on Ephedra,” Salt Lake (Utah) Tribune, August 17, 2006.

77 Gene Emery, “FDA Ban Nearly Wiped Out Poisonings, Deaths from Ephedra,” Reuters Health, May 27, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-fda-ephedra/fda-ban-nearly-wiped-out-deaths-poisonings-from-ephedra-idUSKBN0OC2SR20150527 (last accessed January 24, 2022).

78 Schmuck, “Bechler Receives One Last Ovation.”

79 2003 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 43.

80 Roch Kubatko, “Camden Closure for Bechler Widow,” Baltimore Sun, August 18, 2003: 6D.

Full Name

Steven Scott Bechler

Born

November 18, 1979 at Medford, OR (USA)

Died

February 17, 2003 at Fort Lauderdale, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.