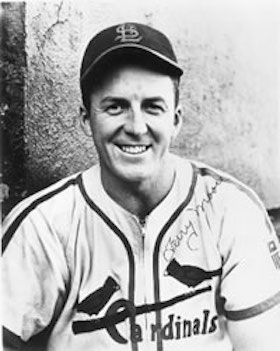

Terry Moore

Teammates remembered his hands — “bear claws for hands,” one said.1 Those powerful hands could pat you on the back or clamp you so hard your knees buckled.

Teammates remembered his hands — “bear claws for hands,” one said.1 Those powerful hands could pat you on the back or clamp you so hard your knees buckled.

No formula can explain leadership, but Terry Moore knew the secret. As center fielder and captain of the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1940s, Moore earned the near-universal respect of his teammates, from the stars to the scrubs. The Cardinals general manager, Branch Rickey, said, “He was particularly valuable because the players respected his ability, his baseball knowledge and his never-say-die spirit.”2

Moore used his huge hands and one of the smallest gloves in the majors to build a reputation as a magician in center field. Rickey named him, Stan Musial, and Chick Hafey as his all-time Cardinal outfield. But because of injuries, many of them products of his breakneck pursuit of flying baseballs, Moore only once played as many as 140 games in a season. He spent three prime years in an army uniform and was never the same player afterward. He made four consecutive All-Star teams, all before his World War II service.

Moore’s career bridged the Gashouse Gang of the 1930s and the St. Louis Swifties of the 1940s. He played with Dizzy Dean and Stan Musial, with Frankie Frisch and Red Schoendienst. Enos Slaughter was his roommate, and Harry “the Hat” Walker named his son Terry.

Terry Bluford Moore was the baby in a family of six boys and two girls, born in Vernon, Alabama, on May 27, 1912, to the former Etta Susan McArthur and James Henry Moore. The family moved to Memphis and then to St. Louis when he was a child. One of his brothers became a dentist, another a professional golfer.

Terry’s parents separated when he was 14. He lived with his mother until he went into the army at age 30. “A big Irish woman,” her son said, Etta “was crazy about baseball. She’d go to a game and when somebody would criticize me, she’d have an umbrella, and, boy, she’d whack them with it!”3

As a teenager Terry went to work to help support his mother and sister. His first job was hauling coal in winter and ice in summer. At 16 he joined the Bemis Bag factory, setting type for the ads that were printed on paper bags. That’s when he began to get serious about playing ball, as a pitcher and outfielder for adult teams.

A bird-dog scout, Bill Walsh, persuaded Rickey to give Moore a tryout and $200. The Cardinals sent him to one of their top farm clubs, in Columbus, Ohio, at the tail-end of the 1932 season. Against that fast competition he went 0-for-7 in three games, but the Cardinals offered him a contract for $75 a month.

Moore knew he could make more than that printing bags and playing semipro ball, so he sat out the 1933 season. The Cardinals enticed him back with $150 a month for 1934. Playing primarily for Columbus, he batted .328 as the Redbirds won the Junior World Series over the International League champion Toronto Maple Leafs.

The Cardinals won the big league World Series in 1934, but the 23-year-old Moore cracked the Gashouse Gang lineup the next spring after just one full season in pro ball. “They were a tough bunch,” he said. “There was always a battle going on, always a fight.”4 The “handsome boy with curly hair and an engaging smile” was a phenom from the start.5 St. Louis Post-Dispatch writer Roy Stockton swooned, “Terry Moore could throw a baseball into a barrel from 100 yards, run 100 yards in 10 seconds and hit the ball a country mile.”6 He batted .287/.314/.414, with a 6-for-6 day in September, before his season ended early when he broke his left leg in an awkward slide. The Sporting News named him to its rookie all-star team.

He was touted as possibly the fastest man in the National League, and his defense drew raves. His first manager, Frankie Frisch, said, “Moore not only had fast starting speed — he also had amazing speed going in any direction, left, right and back.”7 In June 1936, after he made a sprinting backhand grab of a drive by the Giants’ Dick Bartell, New York sportswriter Rud Rennie commented, “He is the best defensive centerfielder either league has seen in a long time.”8 The next day he topped that. Playing the left-handed batting Mel Ott to pull, Moore took off after Ott’s low, screaming liner into left-center. Seeing the ball slicing away, he dived headlong and snared it with his bare hand. “He slid on his belly twenty feet,” Ott said. “It was an impossible catch.”9

Those hands again. “I caught a lot of others with my bare hand,” Moore said. “In fact, I used to practice catching barehanded.”10 He wore a tiny glove with fingers only three inches long so he could squeeze the ball in his claw. He took infield practice to train himself to charge grounders and led National League center fielders in assists four times and in putouts twice. Leo Durocher, a teammate who became manager of the archrival Dodgers, said, “Nobody can tell me a better outfielder ever lived.”11 (Willie Mays was 11 years old at the time.)

Moore paid the price for his hell-bent style. He injured his wrist, shoulders, fingers, legs, and groin. He smashed into the concrete wall at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis in 1938 and suffered a concussion. Another concussion, the result of a beaning in 1941, left him with dizzy spells that persisted into the next season. Moore could find creative ways to hurt himself; he once tore off a fingernail while working on a car.

He was a productive hitter, but never an elite one. “Everybody knows my weakness,” he said, motioning to fastballs high and tight. Slotted first or second in the lineup, the right-handed batter had more walks than strikeouts in his career — twice as many in two seasons. A slender 5’11” and 160 pounds when he came up, he totaled only 20 home runs in his first four years. Then he put on 30 pounds, most of it in his chest and shoulders, and slammed 17 homers in both 1939 and 1940. But he took more pride in his fielding: “Hitting is mostly luck.”12

Manager Billy Southworth named Moore captain of the Cardinals in 1941, recognizing that teammates looked up to him as their leader. “He was the father of the ball club,” third baseman Whitey Kurowski said. “If we had any troubles or anything, we’d go to Terry. He is the one that kept us in good spirits.”13

The captain enforced a hard professional code. Red Schoendienst recalled, “He’d come up to you, grab you [by the shoulder], pinch you and he’d just look at you. He’d say ‘I didn’t think you hustled enough.’ Terry was so damn strong. He’d keep pressing harder and harder and all of a sudden you’d see the guy go down on his knees. He never forgot it.”14

“Terry would chew you out in a nice way,” Harry Walker said. “He’d say, ‘Don’t fraternize with the other team. What are you gonna do if you’ve got to break up the double play and it’s your buddy out there?’ Heck, he wouldn’t let me talk to my own brother.”15 (Harry’s brother Dixie played for the Dodgers.)

Entering his eighth season in 1942, Moore hungered for a pennant. The Cardinals had not tasted the World Series since the year before he joined the club. Rookie Stan Musial won the left-field job to form one of the best outfield combinations of all time with Moore and Slaughter, although they played regularly side by side for only a single season. Rookie Kurowski took over third base, and 21-year-old Johnny Beazley, a big, boisterous right-hander, teamed with Mort Cooper to give St. Louis two of the league’s top pitchers. The Cardinals also had the best catcher, Mort’s brother Walker, and the best shortstop, Marty Marion.

They were a powerhouse team, but they spent most of the season in second place, looking up at the Brooklyn Dodgers. Rickey had sold the Cardinals’ only home run hitter, first baseman Johnny Mize; Slaughter led the club with just 13 homers. Although they stole few bases, they consistently took the extra base, playing Little League ball: run until they tag you. The Sporting News’s Dick Farrington wrote, “The Cardinals are built around speed, hustle and Moore.”16

When the Dodgers pulled 10 games ahead in August, a leading New York bookmaker stopped taking bets on the National League pennant race; it was over. Then the Redbirds got red-hot, winning 44 of their last 53 games. They caught Brooklyn after taking two straight at Ebbets Field on September 11 and 12. Moore told his teammates, “Let’s agree that nobody stays out late until this thing is over. We’ll give all we have and if anybody breaks our own rules — well, we’ll know how to treat him.”17 The Cardinals went 12–2 the rest of way to finish two games ahead of the Dodgers. St. Louis’s 106 victories were the most in the NL since 1909. Moore, despite injuries to a finger and a leg, batted .288/.364/.391.

St. Louis was the underdog in the World Series against the Yankees, who had claimed six of the last seven American League pennants. Game One followed the conventional wisdom. The Yankees’ ace, Red Ruffing, didn’t allow a hit until Moore singled in the eighth. New York knocked out Mort Cooper and took a 7–0 lead into the bottom of the ninth. Ruffing got two men out, then Marion’s triple brought in two runs. Pinch-hitter Ken O’Dea singled home another, and Moore’s single made it 7–4. That was the final score, but the Cardinals had proved — to themselves more than anyone else — that the Yankees weren’t supermen.

St. Louis won the next four in a row. In the sixth inning of Game Three, Moore and Musial chased after Joe DiMaggio’s drive to left-center. Musial dived out of the way, and Moore jumped over his back to make a “leaping, body-twisting, one-handed catch as his hat skittered off his head.”18 The next day Moore frustrated DiMaggio again, hauling in a cloud-scraping fly ball in front of the 457-foot sign in Yankee Stadium’s deep left-center field. Kurowski’s two-run homer off Ruffing in the ninth inning of Game Five clinched the championship.

The Cardinals were young — Moore and second baseman Jimmy Brown were the only regulars older than 27 — and almost entirely homegrown, products of Branch Rickey’s farm system. “I think if the war hadn’t come along we could have won maybe six, seven pennants,” Moore said years later. “We had speed, we had depth, we had pitching, we had hitting.”19

The war. The Cardinals did win two more pennants in 1943 and 1944, but Moore wasn’t there to celebrate. He went to the Panama Canal Zone after the ’42 Series to promote the sale of war bonds. A short time later he returned there as a civilian physical fitness instructor. Apparently officers in the Sixth Army Air Force convinced him that he could qualify for an officer’s commission. When the appointment didn’t come through, he enlisted as a private. He was assigned to the supply room, but his main job was playing baseball.

One historian called the Panama Canal “the most strategic point on the globe” because it moved American warships and supplies between the Atlantic and the Pacific.20 During the war as many as 65,000 soldiers, sailors, and marines guarded the canal. Since the troops were defending against an attack that never came, playing and watching baseball helped ward off boredom. The baseball season began during the dry season in January and sometimes continued until the rains came again in spring.

Some of the troops resented special treatment for the ballplayers. When Moore was granted a furlough to attend part of the 1943 World Series, several soldiers complained to the army newspaper Yank that many men had been in the Canal Zone much longer than he had without even a three-day pass.

Moore led the local league in hitting with a .372 average in 1944 and again the next year with .364. He was also a hit with Penny Flack, a young woman from Provo, Utah, who worked in the canal’s personnel office. They married in January 1945, and their son, Ronald, was born in October.

Discharged from the army in January 1946, Moore reported to a crowded spring training camp in St. Petersburg, Florida. The Cardinals, with the majors’ biggest farm system, welcomed a wealth of talent home from military service. But some of the veterans had been damaged by war. Others found their skills had eroded. Moore, nearing his 34th birthday, was one of them.

“I knew right away in Florida I wasn’t the ballplayer I’d been before the war,” he said later. He was slower and the fastballs looked faster. “I wasn’t a ballplayer at all.”21 He suffered from sore legs and wrenched a knee in an exhibition game.

St. Louis was the favorite to win the 1946 pennant, but the club spent most of the summer chasing the Dodgers. Shaky pitching and unwise deals held them back. Owner Sam Breadon had sold catcher Walker Cooper to the Giants for $175,000 and shipped both of his wartime first basemen, Ray Sanders and Johnny Hopp, to the Braves. Musial moved to first, breaking up the dream outfield.

Despite the club’s success — three pennants in four years — Breadon, who had started his business career selling popcorn, paid his players peanuts. In 1945 Marty Marion and Walker Cooper took home the largest paychecks, just $15,000 apiece. The Cardinals became targets of the Pasquel brothers, who were offering big leaguers big money to jump to their Mexican League. The team’s top starter, Max Lanier, hid his $15,000 bonus inside a radio and headed south. Second baseman Lou Klein and marginal pitcher Fred Martin joined him. The Pasquels waved $50,000 in cashier’s checks in front of Musial, nearly four times his salary, and tempted Moore and Slaughter with stacks of cash. All three stayed put. Breadon rewarded them with bonuses — $5,000 each for the two stars, $1,000 for Moore.

St. Louis caught Brooklyn in August, but the Dodgers wouldn’t fold. From August 23 to the end of the season, both teams went 25-13. Both lost on the final day to finish in a tie for the first time in major league history. St. Louis won two straight in the best-of-three playoff to move on to the World Series against the Boston Red Sox.

Moore went 5-for-10 in the playoff, but he had been a part-timer all season, starting only 65 games. The spring knee injury never healed and his leg muscles were knotted. His .263/.312/.353 batting line was the worst of his career so far.

Still, he played every inning of the World Series, although he managed only four singles and two walks in 31 plate appearances. He showed flashes of his old self in center field, robbing Rudy York with a tumbling catch in Game Four — his former manager, Frankie Frisch, said it was the best he’d ever seen, but the Red Sox believed Moore trapped the ball. He ran down long drives by Ted Williams and Mike Higgins in Game Seven. Slender left-hander Harry Brecheen notched three victories, and Enos Slaughter scored the Series-winning run with his “mad dash” from first to home in the final game.

After offseason knee surgery, Moore was able to start only 116 games in 1947, and his range in the outfield had clearly diminished. Early in the season an explosive newspaper story accused some of the Cardinals of plotting to strike in protest against Jackie Robinson, the Dodgers’ African-American first baseman. Of course, the Cardinals denied it, although Moore acknowledged there had been “some high-sounding strike talk that meant nothing.”22

No hard evidence has ever surfaced to support the story, but the controversy tarred the Cardinals as racists. The players had to deal with the fallout for the rest of their lives. In 1994 the 82-year-old Moore had his lawyer write a letter to a book publisher, demanding a retraction of a charge that he and his friend Slaughter had been the ringleaders in the strike that never happened.23

Moore played part-time in 1948 before retiring at age 36 with a .280/.340/.399 batting line. “The one fellow you can’t kid is yourself,” he said. “I knew I couldn’t do the things I used to do.”24 He joined the Cardinals coaching staff under manager Eddie Dyer.

Dyer was Moore’s favorite manager, and Dyer believed the captain had saved his job more than once by sticking up for him when Sam Breadon was considering a change. Dyer thought Moore “could have been the manager if he had said one word against me.”25 But when Dyer resigned under pressure after the 1950 season, the new owner, Fred Saigh, picked Marty Marion to replace him. Moore stayed on as a coach at Marion’s invitation.

Marion was fired after just one season, and another man with no experience, Eddie Stanky, took over in 1952. Moore remained on the staff for an uncomfortable year; he and Stanky never got along. The club announced Moore’s resignation in November, but he had a different take: “I was fired.” He said the pugnacious Stanky didn’t have the temperament to be a manager.26

Moore took a part-time job scouting for the Philadelphia Phillies while tending to his businesses. He owned two bowling alleys with restaurants in the St. Louis area, which were managed by his brother Frank, who also ran a golf club, and France Laux, a former Cardinals broadcaster. Moore said, “I got ’em so I’d have a business when I quit playing and wouldn’t be tempted to become a manager.”27

He succumbed to temptation when a man he had never met hired him to manage a team he had barely seen. In July 1954 Roy Hamey became the Phillies general manager. His first act: fire the manager, 63-year-old Steve O’Neill. Hamey went to see Moore, introduced himself, and offered him the job.

“The appointment of Moore is a shot in the dark,” Hamey said. “I know that Terry has never managed before, but he is a young man. He has always been an alert, hustling ball player. It’s the kind of spirit that Terry always showed as a ball player that I want instilled into our team.”28 It was a shot in the dark for Moore, too. He had attended only one Phillies game, a spring exhibition.

When Moore took over after the All-Star break, the club promptly lost four straight. On July 18 the Phillies went to St. Louis for a Sunday doubleheader. They won the rain-delayed first game and carried an 8–1 lead into the fifth inning of the nightcap. Philadelphia’s Earl Torgeson ducked a close pitch and got into a fight with the Cardinals catcher, Sal Yvars. As Moore ran to home plate to protect his man, here came Eddie Stanky charging out of the Cardinals dugout. Stanky tackled Moore, and the managers rolled on the ground punching out their longstanding hostility. After order was restored, Stanky was suspended for five games; Moore was not disciplined. The umpires forfeited the game to Philadelphia because they accused Stanky of stalling to wait for more rain.

Barely a month after he arrived in Philadelphia, Moore paved his way out. He told a reporter that he had a verbal agreement to return in 1955, but had not told the players. “I wanted them to think I was a fill-in for half a season,” he explained. “That way I figure to find out what men would hustle and those who would try to take advantage of the fact that they didn’t have to impress me.”29 He suggested that some of the players weren’t giving their all and some were spending too many hours carousing.

Naturally, that didn’t go down well. Captain and second baseman Granny Hamner confronted the manager. Hamner was also angry because he believed the front office had a detective following him and others. Although Moore and Hamner shook hands and said they had made up, the clubhouse was seething. The Phillies had played slightly better than .500 ball for Steve O’Neill, but they went 35-42 under Moore and finished a distant fourth.

Hamey dumped Moore after the season, saying he wanted an experienced manager. His choice was a minor league manager, Mayo Smith, a man he knew from their days in the Yankees farm system.

Moore returned to the Cardinals as a coach in 1956, when Fred Hutchinson became manager, and stayed for three years before leaving baseball. He and his wife, Penny, divorced in 1957. They had two children, son Ronald and daughter Terry Lee. In 1960 Moore married Patricia Wilson, a former nightclub singer. They lived in Collinsville, Illinois, across the Mississippi River from St. Louis.

Over the years he endured a plague of business misfortunes. A nightclub and a bowling alley he owned both burned. A tornado demolished another of his bowling lanes. Burglars stole one of his World Series rings.

Terry Moore died at 82 on March 29, 1995, after a long illness. The chronicler of his Cardinal teams, the Post-Dispatch’s Bob Broeg, wrote, “For a chance to play a boy’s game as a man, he was always grateful.”30

Notes

1 Jerome M. Mileur, High Flying Birds: The 1942 St. Louis Cardinals (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2009), 70. That was Whitey Kurowski’s description.

2 “Rickey Lauds Moore,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1943, 14.

3 Cynthia J. Wilber, For the Love of the Game (New York: William Morrow, 1992), 221.

4 Ibid.

5 J.G. Taylor Spink, “3 and 1,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1936: 4.

6 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Harper Entertainment, 2000), 203.

7 Grantland Rice, “Speaker, DiMaggio, Moore Held Top Defensive Fielders,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 27, 1945: 10.

8 Jason Aronoff, Going, Going…Caught (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 116.

9 Stanley Frank, “There’s Only One Moore,” Colliers, July 4, 1942: 19.

10 Aronoff, 117.

11 Frank, 19.

12 Ibid., 20.

13 Mileur, 70.

14 Rick Hummel, “Schoendienst on Moore: He Knew How to Win,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 31, 1995, 7D.

15 George Vecsey, Stan Musial: An American Life (New York: ESPN, 2011), 129.

16 Dick Farrington, “Terry Moore, ‘Best Friend of Cardinals’ Moundsters,’ Shakes off Head Injury and Heads for his Best Year,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1942, 3.

17 “Billy Werber Retires,” Ibid., September 17, 1942, 15.

18 Shirley Povich, “Ernie White Pitches Cards to 2-0 Shutout over Yanks,” Washington Post, October 4, 1942, 1.

19 Walter Langford interview with Terry Moore, July 18, 1982, in Collinsville, Illinois. SABR Oral History Committee.

20 “Panama Canal – Defending the Canal,” globalsecurity.org, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/facility/panama-canal-defense.html, accessed November 11, 2015.

21 Frederick Turner, When the Boys Came Back (New York: Henry Holt, 1996), 85; Rick Hines, “Terry Moore: One of the Best Centerfielders Ever,” Sports Collectors Digest, April 3, 1992, 101.

22 Bob Broeg, “Cardinal Players Deny They Planned Protest Strike Against Robinson,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 9, 1947: 9C.

23 W. Ray Raleigh letter to William Morrow and Company, June 23, 1994, in Moore’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

24 Arthur Daley, “The Captain Retires,” New York Times, April 3, 1949, S2.

25 Stan Baumgartner, “Goodbye Note in Dyer Talk?” The Sporting News, September 20, 1950, 4.

26 “Moore Fires Blast at Stanky,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 12, 1952, in Moore’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

27 John P. Carmichael, “The Barbershop,” Chicago Daily News, August 28, 1954, in Moore’s HOF file.

28 “Ex-Cardinal Great Named by Roy Hamey,” Associated Press-Greensboro (North Carolina) Daily News, July 16, 1954, 29.

29 Ray Kelly, “Moore to Stay with Phils But His Ruse Kept Team in Dark,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, August 23, 1954, 23.

30 Bob Broeg, “Sympathy Swings in the Face of Pious Ballplayers,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 5, 1995, 6D.

Full Name

Terry Bluford Moore

Born

May 27, 1912 at Vernon, AL (USA)

Died

March 29, 1995 at Collinsville, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.