September 30, 1942: Yankees’ Red Ruffing wins World Series opener in St. Louis

Usually the opening game of a World Series generates a great deal of excitement. Hometown fans are thrilled that their club has reached the ultimate series to determine who will reign as the world champion. While that occurred in 1942, it played out against a different, more somber backdrop.

Usually the opening game of a World Series generates a great deal of excitement. Hometown fans are thrilled that their club has reached the ultimate series to determine who will reign as the world champion. While that occurred in 1942, it played out against a different, more somber backdrop.

World War II was well under way. All attention was focused on the horrific conflict between German and Russian forces to determine who would gain mastery over Stalingrad. Nearer to home, hearts were with sons, brothers, fathers, and other loved ones in the Pacific, where at that moment the US struggle to hold Guadalcanal against repeated Japanese efforts captured daily newspaper headlines. The war demanded concern. The Series offered momentary distraction from that concern.

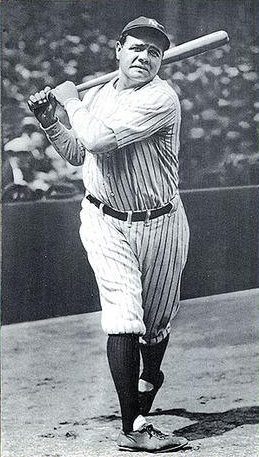

Specifically, that distraction would take place at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis, where the hometown Cardinals were appearing in the World Series for the first time since 1934. Their rivals were the New York Yankees, favored to win, favored at 4-to-1 odds.1 Those odds were born of considerable logic. The Yankees had appeared in 12 Series, including five of the last six, during which they won 20 of 24 games, including sweeps in 1938 and 1939. Their roster included the likes of Joe DiMaggio, Bill Dickey, Charlie Keller, Phil Rizzuto, and Joe Gordon, who would be named the American League Most Valuable Player for 1942. DiMaggio, Gordon, and Keller each drove in over 100 runs for a team that led the league in runs scored. The pitching staff, equally adept, contained such talents as Tiny Bonham (21-5), Spud Chandler (16-5), and Red Ruffing (14-7). At 2.91, their team ERA was the American League’s best. Their 13th pennant was a foregone conclusion by the end of August. They finished nine games ahead of the Boston Red Sox.

Not only did the Yankees have a strong team, they also were familiar with Sportsman’s Park, having regularly played the American League Browns there during the regular season. Thus any hometown advantage the Cardinals might have enjoyed, their familiarity with the poorly maintained infield that plagued visiting players, or the idiosyncrasies of play in the outfield, was largely negated.2

The Cardinals, by contrast, had to generate a stunning 21-4 run in September, part of a 44-9 effort, to pull ahead of the Brooklyn Dodgers, clinching the pennant on the last day of the season. They too led their league in hitting and runs scored. Their ERA of 2.55 was easily the best in the majors. As opposed to the mostly veteran Yankees, the Cardinals lineup was made up of relative youngsters like 21-year-old Stan Musial, 24-year-old Whitey Kurowski, and 25-year-old Marty Marion. Twenty-four-year-old rookie Johnny Beazley (21-6) and Mort Cooper (22-7) led the pitching staff. Overall, the team was nearly two years younger than its American League counterparts. Unlike the Yankees, the Cardinals’ experience in the World Series was virtually nil.3

Overshadowing all was a constant reminder that World War II was its height. These reminders manifested themselves in various ways. Military personnel around the world were able to hear the Series via shortwave radio, and the Army Emergency Relief Fund received part of the gate receipts.4 The war effort had priority on rail transportation. Giants manager Mel Ott, bumped off his train en route to the Series by military personnel, never made it. He returned to New York. Johnny Sturm, the Yankees’ first baseman in the 1941 World Series, was on hand to watch the game – as a corporal in the Army. Lieutenant Hank Greenberg, the 1940 Most Valuable Player, attended as well.5 But for the war, both players would have been on major-league rosters. Dozens of other players serving in various branches of the military could have made the same claim.

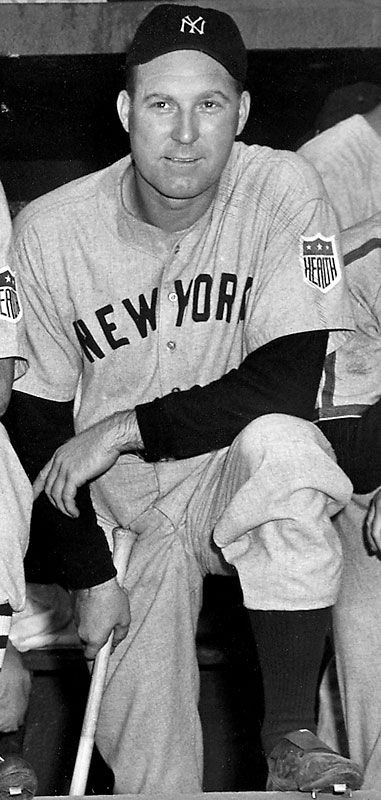

Managerial talent for the Series pitted experience vs. newness. Yankees skipper Joe McCarthy was looking for his seventh championship. His counterpart, Billy Southworth, was looking for his first. Southworth had managed St. Louis in 1929 for part of the season. The team got off to a mediocre start and Southworth lost his job, demoted to manage the Cardinals’ minor-league team in Rochester. After several years, he left baseball. Eventually he rejoined the Cardinals organization and in 1940 received the call to take over the Redbirds. Now he was facing the most successful manager in World Series history. Southworth choose Mort Cooper to start. His 22-7 record, compiled on the strength of a league-leading 1.78 ERA, made Cooper’s selection an easy one.

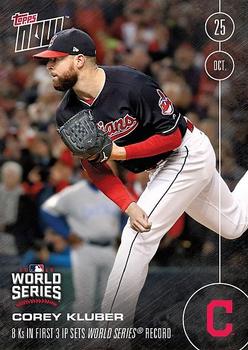

McCarthy named Red Ruffing to open the Series. The 37-year-old Ruffing had solid credentials in postseason play. He held the record for most World Series victories (six); he had started eight Series games. This was his seventh World Series. There were 34,769 fans at Sportsman’s Park to see the apparent David vs. Goliath contest. New York drew first blood in the fourth on DiMaggio’s single, a walk to Dickey, and Buddy Hassett’s RBI double. The Yankees scored again in the fifth on Red Rolfe’s single, Roy Cullenbine’s double, and a run-scoring infield grounder, making it 2-0.

In the eighth New York struck again with three runs on three hits and a dropped fly ball by Enos Slaughter in left. The 5-0 lead appeared to be more than enough for Ruffing, who had kept the Cardinals from scoring. And hitting. The Redbirds were hitless through seven. In the bottom of the eighth Ruffing struck out Harry Walker and got Jimmy Brown to pop up to Rizzuto. With Brown’s popup Ruffing set a record – no other pitcher had gone so deep into a Series game without allowing a hit. Former teammate Monte Pearson had no-hit the Reds in 1939’s World Series before giving up a single to Ernie Lombardi with one out in the eighth. Another former teammate, Herb Pennock, had also pitched 7⅓ innings of hitless ball in 1927 against the Pirates. Both times the Yankees had gone on to sweep the Series.

Pennock was four outs away from pitching the first no-hitter in World Series history. Then, with two outs in the eighth, Terry Moore, the Redbirds’ center fielder, broke Ruffing’s hold by singling to right. Any solace the Cardinals might have gained from breaking up Ruffing’s hitless effort vanished in the top of the ninth when New York scored two more runs thanks to two errors on throws by relief pitcher Max Lanier. Going into the bottom of the ninth, St. Louis was down 7-0.

Musial popped out to Dickey to open the ninth. Walker Cooper, Mort’s brother and batterymate, reached on an infield hit – just the second hit off Ruffing. When Johnny Hopp flied out to left it looked as if Ruffing was going to pick up his eighth complete game in World Series play, but it was not to be. Three hits (including Marion’s two-run triple and Ken O’ Dea’s RBI single) and a walk later, McCarthy was forced to relieve Ruffing with Spud Chandler. Moore and Slaughter greeted Chandler with singles. The bases were loaded, the score stood at 7-4. The Cardinals had batted around and Musial came to bat once again. Musial had made the first out of the inning; he would make the last out, grounding to Hassett at first, who flipped the ball to Chandler for the final putout.

New York had firmly handled the Redbirds until the ninth. They had almost let the game get away from them. Ruffing received credit for his seventh and final World Series win. His record stood until Whitey Ford broke it 19 years later, in 1961, when Ford achieved the eighth of what would become a record 10 World Series victories.

The Yankees had won the ninth opening game of the last 10 World Series in which they had appeared. This victory served to reinforce the feeling that they would make quick work of the less-experienced Cardinals. The 4-to-1 odds laid out before the Series looked more and more like a sure thing.

St. Louis had played sloppily, with four errors leading to four unearned runs. Their ace, Mort Cooper, had not impressed the home crowd. He had given up five runs in 7⅔ innings. Ruffing had stymied the offense until the ninth. It was a daunting experience. St. Louis needed to win the next game – no team had ever emerged victorious in a best-of-seven World Series after losing the first two games.6

While they looked bad, the Cardinals had confidence in themselves. As Musial later recalled, “In ’42 we played the New York Yankees during spring training and beat them three out of five games. We played against them all the time in the spring and that was a plus. We knew they were a tough club, a good club, but the Yankees didn’t faze us.”7

Did Musial’s perspective have merit? Was the Redbirds’ rally in the ninth an omen of things to come or a last-gasp effort? The Cardinals would soon find out.

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 Jack Cavanaugh, Season of ’42: Joe D., Teddy Ballgame, and Baseball’s Fight to Survive a Turbulent First Year of War (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012), 234-235.

2 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, 2000), 232.

3 Cardinals with previous World Series exposure were limited to reserve catcher Ken O’Dea, closer Harry Gumbert, and reliever Whitey Moore, each of whose experience was limited.

4 Bill Gilbert, They Also Served, Baseball and the Home Front,1941-1945 (New York: Crown Publishers Inc., 1992), 70.

5 “Notes of Yank Victory in Curtain-Raiser,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1942: 13.

7 Golenbock, 244.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 7

St. Louis Cardinals 4

Game 1, WS

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.