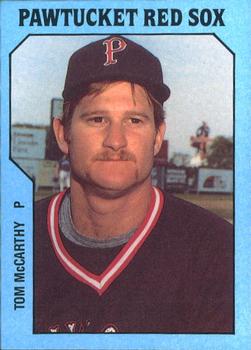

Tom McCarthy

Thomas Michael McCarthy was a right-handed pitcher who battled his way through a considerable number of injuries and pitched in the major leagues for the Boston Red Sox (1985) and Chicago White Sox (1988 and 1989). He also toiled through 15 years of minor-league baseball, most of them at the Triple-A level. Though he never had a decision in three games with the Red Sox, he wrapped up his major-league career with a winning record of 3-2, plus a save, for the White Sox, earned over the course of 37 relief appearances during 1988 and 1989.

Thomas Michael McCarthy was a right-handed pitcher who battled his way through a considerable number of injuries and pitched in the major leagues for the Boston Red Sox (1985) and Chicago White Sox (1988 and 1989). He also toiled through 15 years of minor-league baseball, most of them at the Triple-A level. Though he never had a decision in three games with the Red Sox, he wrapped up his major-league career with a winning record of 3-2, plus a save, for the White Sox, earned over the course of 37 relief appearances during 1988 and 1989.

One of only three major-league ballplayers to have been born in Landstuhl, Germany, Thomas Michael McCarthy came into the world on June 18, 1961. “My father was in the Air Force,” McCarthy said in an August 2020 interview with the author. “I was just born there. When I was old enough to fly back to the States, we did. I think it was maybe a month or so.”1

He wasn’t the first pitcher named Tom McCarthy who had pitched for a major-league team in Boston. Right-hander Thomas Patrick McCarthy had pitched in 22 games in 1908 and 1909 for the National League’s Boston Doves, precursor to the Boston Braves.2

As an Air Force family, the McCarthys lived in a number of places, from California to Florida before ultimately settling in Massachusetts. “I’ve got four sisters—two older [Leslie and Donna] and two younger [Kathleen and Sueann]—and one brother [William], a year-and-a-half younger than I am,” McCarthy said.

Both parents, Ronald Thomas McCarthy and Carole Ann (Perron) McCarthy, were natives of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Ronald McCarthy was a career Air Force man who put in 25 years of service time and then worked another five years or so as a civilian employee training new people. “I believe he was a staff sergeant. From what I understood, he worked on the cockpits in the F-106s—the instruments and everything. All I know is that he put on his Air Force uniform and went to work.” He was stationed at Otis Air Force Base, on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The family purchased a house in Manomet, a village in Plymouth. Carole McCarthy worked as a night-time switchboard operator at Jordan Hospital in Plymouth (now Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital-Plymouth). She worked the night shift for over 20 years.

Tom attended Plymouth schools from eighth grade through high school.

McCarthy had played both shortstop and pitcher in high school, hitting close to .400 in his junior year but dropping to .270 in his senior year as he shifted his focus to pitching. In his senior year at Plymouth-Carver, he was 6-2 with a 1.01 earned run average. He threw two no-hitters and a two-hitter. He struck out 70 batters in 45 innings of work.3

While still at Plymouth-Carver High School, McCarthy was selected by the Boston Red Sox in the seventh round of the June 1979 amateur draft. Six years later he made it to the majors.

Red Sox scout Bill Enos is credited with his signing. “He called me the day I was drafted. I answered the phone at the house. He goes. ‘Can I speak to Tom McCarthy?’ I said, ‘Well, this is he.’ He goes, ‘Well, this is Bill Enos from the Boston Red Sox. You’ve just been drafted by the Red Sox. What do you think?’ I said, ‘Ma, this is for you.’ I couldn’t believe it. She was behind me; she was my number one fan, that’s for sure. He [Enos] pulled up in a big old Town Car. Either a Town Car or a Cadillac. I think it was a Town Car.” They came to terms.

Things weren’t so easy for the 18-year-old after he reported to the Single-A, short-season Elmira Pioneers in the New York-Penn League. His record was 2-6 with a 7.04 ERA. His WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) was a high 2.261. But he was just getting his feet wet in professional baseball. And, he explained later, “They changed my delivery over that first Instructional League. Then it was changed over a couple of more times.”4

In 1980, McCarthy started the season with three games for Elmira, where he won two of his three decisions, with a 3.15 ERA. Most of his work was for the Winston-Salem Red Sox Class A (Carolina League). He had a 4-4 record with an ERA of 3.98.

The 180-pound McCarthy stood an even six-feet tall. He spent three more seasons with Winston-Salem, under three different managers: Buddy Hunter, Rac Slider, and Bill Slack.5 In 28 games (18 starts) in 1981, McCarthy regressed statistically to a 7.29 ERA (his won/loss record was 3-7). In 1982, he appeared in 30 games, 15 of them starts. He improved his earned run average to 6.53 but he was 3-11 for the last-place team that finished 45 1/2 games behind the division-leading Peninsula Pilots. Back in instructional league that fall, he developed a blood clot in his left shoulder and ended up in the intensive care unit in Winter Haven, Florida.

In 1983, used more in relief (only eight of his 35 appearances were as a starter), McCarthy progressed further at Winston-Salem. He improved his ERA significantly, to 4.13, and had an 8-6 record. He struck out 100 batters and walked 54 in 98 innings. He said he “knew I’d found what I’m supposed to do.”6

Had he felt stuck at Single-A ball, spending nearly four seasons in Winston-Salem? “I was so young then. The managers … I wouldn’t have changed it at all because I learned so much from each one of the managers. Buddy Hunter was the first. Bill Slack was probably the most knowledgeable about pitching. Rac Slider was probably the one who gave me more … let me know more about what the mental game was all about. Even though I spent that much time there, it was more beneficial for me in the long run. After I moved up, I was in Triple A most of the rest of my career if I was not in the major leagues.”

In 1984, McCarthy was promoted to Double A, pitching for the Eastern League’s New Britain Red Sox. He only started one game. He relieved in 37, 27 times closing out the game. His ERA was a very good 3.06. He struck out 65 and walked 56, prompting Red Sox farm system head Ed Kenney to say, “When McCarthy gets the ball over, he can pitch anywhere. But he can be a little like Mark Clear—walk four in a row.”7 McCarthy was still only 23 years old.

In both 1983 and 1984 he had suffered physical problems. Over the winter of 1984-5, he said he visited Boston-area dentist Dr. Gerald Maher “who fitted me for a mouthpiece similar to the one [boxer] Marvin Hagler uses, and he thinks that what it does to the cardiovascular system through the neck muscles will help me [gain more velocity].”8

As spring training began in 1985, manager John McNamara said, “No one thus far has shown me that he can throw any harder than McCarthy”—this on a staff that included Roger Clemens.

Pitching coach Bill Fischer added, “Anyone who can throw that hard can strike people out in the big leagues. If he doesn’t let things mess him up, he’s got a chance to be a legitimate power reliever. Now I want to see what he does as we go from stage to stage.”9

In early March 1985, McCarthy flew back to Boston for the birth of his first child, son Jordan. He and his wife Jane McCarthy had three children in all—daughter Taite was born in 1990 and son Jackson in 1996.

McCarthy was placed with the Red Sox Triple-A affiliate in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. On July 2, Red Sox catcher Marc Sullivan suffered a broken left wrist on a foul tip; further, outfielder Tony Armas had his disabled-list stay extended from 15 days to 21 days. The Boston club decided to call up Tom McCarthy. He was 4-4 at the time and hadn’t given up an earned run in any of his last three outings. On July 2, he’d been named co-pitcher of the week in the International League. Oddly enough, he had been switched back to become a starter once more and had seemed to find a groove.

“I wasn’t pitching as regularly as I could have been and wasn’t able to stay as sharp as I wanted to be,” he said on joining the team in Anaheim. PawSox manager Rac Slider made some moves. “Rac switched everybody, and the starters wound up in the bullpen. That’s when I started to get some innings and started to get back to where I felt I should be … I never had that many control problems. I was always around the plate. It was just that I needed more consistency with my breaking pitch, and I found it in the starting rotation.”10 He had nine starts under his belt when he was summoned, and an overall 3.16 ERA. “Working as a starter has helped me … I have a good fastball and need to be just as consistent with my other pitches.” For someone who had, in earlier years, been a starter, it was interesting to hear him add, “Starting took some getting used to, but it was fun, and I was glad I got the opportunity. Now I know I can do starting and relieving. I guess I proved to them I’m a little versatile.”11

John McNamara planned to use McCarthy as a long reliever. He was brought up to Boston on July 3, traveled cross-country to California and arrived on July 4. He got into his first game on July 5, 1985.

It was a Friday night game against a good California Angels team, in first place in the American League West. Boston was in fifth place in the AL East. The Angels had a 9-4 lead after five innings. With the score unchanged heading to the bottom of the eighth inning, McNamara had McCarthy take the mound. A single, a walk, a fly ball to right, and another walk loaded the bases. Doug DeCinces doubled to drive in two. Daryl Sconiers hit a fly ball to center field, deep enough to bring in a third run. Dick Schofield singled to drive in DeCinces with a fourth run before a groundout ended the inning.

It was, wrote Joe Giuliotti of the Boston Herald, “a tough major-league debut … [b]ut he did impress scouts with his arm. Said Pittsburgh Pirates scouting supervisor Howie Haak: ‘[H]e looked like he had a strong arm and he threw hard. But he has to get the ball down. If he stays where he was last night, he’ll get killed.’”12

McCarthy had two more outings, one on July 7 while still in Anaheim, followed by a third one in Boston on July 27 against the visiting Seattle Mariners. Each outing was better than the one before. On Sunday afternoon, July 7, Jim Dorsey started for the Sox but was hit for six runs over the first 3 2/3 innings. After a two-run homer by Reggie Jackson, Dorsey walked the bases loaded. McNamara made a change, and McCarthy came in to relieve. A single allowed two inherited runners to score, but then he got out of the inning. He had a 1-2-3 fifth (including retiring future Hall of Famer Rod Carew) but the Angels led off the sixth with a single (also by Jackson) and a homer. Mark Clear relieved McCarthy. On Saturday afternoon, July 27, McCarthy entered the game in the top of the seventh, with Seattle ahead, 9-2. He uncorked a wild pitch, allowing the 10 th run to score, but then worked 2 2/3 innings, allowing just one single and a couple of walks while recording his first two major-league strikeouts, of Alvin Davis and Ivan Calderon. He had progressively brought down his ERA from 36.00 to 23.14 to 10.80 over his five innings of work in the majors.

On July 30, when Marc Sullivan was activated, McCarthy was returned to Pawtucket and remained there for the rest of the season. By year’s end, his Triple-A ERA had nudged up from 3.16 to a still-respectful 3.59 on the year.

Most of the mentions of Tom McCarthy in sports page coverage—even in the Boston area—during the first half of the 1980s were regarding NHL hockey star Tom McCarthy who played seven seasons with the Minnesota North Stars. To confuse matters, hockey’s McCarthy played for the Boston Bruins in 1986-87 and 1987-88.

Before the end of 1985, however, baseball’s Tom McCarthy had been traded to the New York Mets as part of an eight-player trade on November 13. The Mets’ main goal in the trade was to acquire pitcher Bobby Ojeda.

McCarthy worked 1986 in the International League again, with the Mets’ Triple-A affiliate the Tidewater Tides, pitching to a 3-2 record and 4.04 ERA, with roughly two-thirds of his appearances being in relief. He missed the last five weeks of the season on the disabled list. He had a rib removed on his left side and a blood clot which had formed under his left shoulder blade.

McCarthy spent most of 1987 in Mississippi playing Double-A ball for the Texas League’s Jackson Mets. His won-lost record of 1-4 was not representative of his pitching; he had a 2.65 ERA. He appeared in 10 games back with Tidewater also and was 0-2 with a 4.26 ERA.

For the second year in a row, he was invited to spring training as a non-roster player. He began the 1988 season with Tidewater again and in 34 games (three starts) was 8-3 with a 2.67 ERA. The Mets knew McCarthy would be reaching free agency at the end of the season, and with a dominant pitching staff at the major-league level, McCarthy had not been called up from the minors. On August 4, the Chicago White Sox acquired him in a four-player trade with the Mets.

He was brought up to the big-league club in September and made six relief appearances from September 17 to October 2, throwing a total of 13 innings and allowing just two runs, for an impressive ERA of 1.38.

The second of the six appearances was on September 18 at the Metrodome in Minneapolis. The Twins held a 3-2 lead when McCarthy came in to work the fifth inning. Kirby Puckett hit a ball to deep center field, but it was caught for the first out. McCarthy then hit a batter and walked the next one, before inducing an inning-ending double play. He also got through the sixth without allowing a run, and then saw his teammates score five runs in the top of the seventh. The first two Twins batters in the seventh doubled and then singled, so White Sox manager Jim Fregosi replaced McCarthy. One of the runs scored, but by game’s end, Chicago won, 8-5, and Tom McCarthy had his first major-league win.

He earned a second win nine days later against the Texas Rangers in Chicago. This time he relieved Shawn Hillegas, who had held the Rangers to two runs through the first six innings. The game was tied, 2-2, when McCarthy took the mound in the top of the seventh. He faced nine batters and retired every one of them, and got the 3-2 win thanks to a solo home run by Mike Diaz in the bottom of the eighth. His last game of 1988 earned him his only major-league save, working three innings of two-hit ball in Kansas City.

In 1989, he was up-and-down between the Triple-A Vancouver Canadians (Pacific Coast League) and the White Sox. He started the season with Vancouver and was brought up from May 7 to June 30, then again from August 1 through the end of the season. The first time he was sent down, veteran catcher Carlton Fisk was “upset over [McCarthy’s] demotion.”13

In all, with the Canadians he was 2-4 (5.40, over 26 2/3 innings), while with the White Sox he was much better (1-2, 3.51, in 31 appearances and a total of 66 2/3 innings.) In each of his two losses, McCarthy pitched more than three innings and allowed two runs. Two of the four runs were unearned. The win was in Chicago on August 9 against visiting Oakland. In the top of the 11 th inning, the Athletics got a man on second base with one out and Fregosi called on McCarthy to replace Ken Patterson. He induced two groundouts, the second by Rickey Henderson, then saw the White Sox win the game on three consecutive one-out singles, the game-winner belonging to Fisk.

After the 1989 season, due to numbness he had felt in his arm, he had his upper right rib surgically removed on October 24. Doctors hoped “the removal will enable proper circulation in his arms.”14 It was his second rib removal, and it was known that there would be a lengthy recovery and rehabilitation period. “They said I was born with an extra rib. McCarthy believes the surgery may have come with an unintended side effect of nerve damage to a shoulder blade. His contract had been assigned to Vancouver as the year opened. He’d started throwing during spring training, but the nerve damage forced him to suspend.15 He ended up missing the entire 1990 season and was released by the White Sox at the end of the season.

“They didn’t know if I’d ever be able to pitch again, so the White Sox let me go. I signed on with the Braves. They sent me down to Triple A, to get more work in. I had a good spring training. I thought I was going to make the team, but it just didn’t work out that way.”

McCarthy returned to the International League in 1991, 1992, and 1993. He pitched for the Richmond Braves the first two years, with identical 4-6 records and ERAs of 4.24 and 3.21. He mixed starting (13 games) and relieving (8 games) in 1991 but was almost exclusively a reliever in 1992—all but three of his 48 appearances were in relief. In 1993 he pitched for the Charlotte Knights in the Cleveland Indians organization; he was 6-5 (4.11) in 43 relief stints and two starts.

In 1994, he pitched in Mexico, for two different teams: Los Pericos de Puebla and Los Diablos Rojos del Mexico in Mexico City. His statistics for such teams are not available as of the time of this writing.

His final professional year was 1995. Over the winter of 1994-95, he played in Puerto Rico. Major-league players had gone on strike late in the 1994 season, bringing about the cancelation of that year’s World Series. In the springtime, with matters still not resolved, teams were seeking replacement players to step in, and McCarthy was among those reported as willing to serve as replacement players. In fact, he was named as the Opening Day starter for the Dodgers, to pitch in the April 3 game against the Florida Marlins. “It’s a great honor,” he said. “I mean, the last time I was anybody’s opening-day starter was when I pitched for Charlotte against Ottawa in ’93. I guess I’ve come a long ways, huh?”16 The replacement players left spring training to take a charter back to Los Angeles, amidst rumors that a settlement might be coming. “A week ago, I was convinced we’d be opening the season,” he said. “Now you don’t know what will happen.”17

Instead, the strike was suspended on April 2, and McCarthy was promptly assigned to Albuquerque. The season opened on April 25, with Ramon Martinez pitching for the Dodgers. McCarthy pitched for the Albuquerque Dukes—eight starts and five relief appearances, producing a 3-3 record and a 6.00 ERA in 48 innings.

Again, an injury prevented him from continuing. This time it was a career-ending injury. “In ’95, I was with Albuquerque, pitching in Edmonton against Oakland’s Triple-A team. I had pitched the day before and the day before that. When we got to Edmonton, even though it was in June, it was pretty cold that evening. The other relief pitchers weren’t able to throw and Rick Dempsey, who was my manager at the time asked me if I could give him an inning if he needed me. I said, ‘Yeah, I could probably give you an inning, but that’s about it.’ My arm was sore. I believe it was either the third or fourth inning, he calls down to the bullpen and tells me to get up. I threw two or three pitches in the bullpen and then they called me into the game. I wasn’t really warmed up at all. I got to the mound, and I threw 10 pitches, because that was my limit. I asked the umpire for an extra one or two because the weather was cold and he said ‘Okay,’ but I still wasn’t really warmed up. I proceeded to tear every ligament and tissue and muscle in my shoulder.”

McCarthy still wasn’t ready to give up. “I tried to get back in the game. I rehabbed for pretty much a whole year. Every day I’d go to the rehab and get on the machine and work my arm. I had a tryout. Did well. I knew a scout and he let me pitch for him. I was doing well, I had my fastball back in the low 90’s. He called me the next day and wanted to see how I felt. I just told him. ‘I’m going to have to hang it up. I can’t even get out of bed today.’”

Tom McCarthy pitched professionally through the 1995 season, working in Triple-A ball in the Braves, Indians, and Dodgers systems, but never got another call to appear in a major-league game. His major-league record was 3-2 and one save, working in 40 games with an earned run average of 3.61 over the course of 84 2/3 innings. He never had an at-bat. He handled every one of his 22 fielding changes without an error.

He pitched in 445 minor-league games, starting in 108 games. Perhaps oddly, his 4.43 ERA over the 15 seasons was significantly higher than his major-league ERA. When he did bat in minor-league ball, he struck out in 15 of his 30 at-bats, but did collect a couple of doubles, recorded four RBIs, and hit for a .133 average.

Tom McCarthy had mentored a couple of younger pitchers during his latter minor-league years. “When I was with the Triple-A Dodgers, they had Chan Ho Park room with me and I basically had to teach him a lot about how American baseball is played. He threw hard as hell, but he was young and raw as far as the mental aspect of the game. We had a few issues trying to communicate, but when it came to sports it was like a universal language. I thought I helped him out.”18

“When I was with Richmond, they had me room with Mark Wohlers for a while. He was their up-and-coming stopper. They wanted me to see how he’s thinking. I was an older guy, a knowledgeable guy, and I was a good teacher. I had coaches tell me this. That’s why I really wanted to get into coaching, but it never panned out.”

He tried to get into scouting as well, but that didn’t come to pass, either.

After baseball, McCarthy sold automobiles for a while. “I first started selling cars, down here in North Carolina. I moved down here when my first son was born, back in ’85. We got a place down here. I moved back [to Massachusetts] when my wife and I got separated.”

There was some other work as well before he settled on a profession. “Right now, I’m a truck driver. Pretty much taught myself how to drive a tractor-trailer. I learned how to do that in Massachusetts. I worked for a company called Lambert’s Fruit. They were on the Cape, in Hyannis. My boss asked me if I knew how to drive a tractor-trailer. I said, ‘Well, if it’s got wheels, I can drive it. I just don’t have a license to drive it legally.’ He said, ‘Well, if you get your permit, we can get somebody who has a license, and you can go to the produce up in Boston and pick up our produce and bring it back every day.’ So, I did. Went and got my permit. About a week or so later, they had somebody who had a CDL (commercial driver’s license) ride with me and I was driving to Boston every day.”

He then relocated back to central North Carolina. “I drove for FedEx for five years, over the road. I’d go back and forth to California probably once a week. But that got old. I hated living out of my truck. That truck never stopped. I had a co-driver, so when I was done driving, he was driving, and when he was finished driving, I’d jump back in the seat. It never stopped. We could make it to California in 2 ½ days.”

Now he drives nights. “I deliver for ALDI Grocery Stores. They’re actually the third largest grocery store chain in the United States now. I deliver at night when there’s usually nobody there.”

And there is yet more surgery in his future. “I’ve learned to live with pain,” he says. “I drive a tractor-trailer, but I really don’t do a lot of physical labor. Everything is done with a jack or something like that.” He was advised by a doctor that his shoulder couldn’t have another operation. He needs a total replacement.

Does he still follow baseball? “I keep a little track of it, but not as much as I used to. Baseball was good to me—don’t get me wrong—but when I tried to get back into it, it was like since you were gone … out of sight, out of mind.”

Asked about his children, McCarthy showed parental pride, “My oldest boy, Jordan, is a teacher. He teaches phys ed., coaches football, basketball, baseball, wrestling, whatever. He’s very into sports and athletics. My daughter Taite, she is the wild child, but she’s got a good head on her shoulders. She’s a bartender. Right now, she’s out of work [due to the COVID-19 pandemic]. My youngest son, Jackson, is a music minister. Christian music. He can sing anything. When he sang at my mother’s funeral, the church that he sang for—where we had the service—wanted to hire him for the summer. He lives in Atlanta. I told him he needs to talk to some agents and see if he can start singing professionally. He can sing anything.”

Last revised: February 11, 2022

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Joel Barnhart and fact-checked by Steve Ferenchick.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied on Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org, and research materials available on www.sabr.org.

Notes

1 Author interview with Tom McCarthy on August 20, 2020. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations from McCarthy come from this interview. The municipality of Landstuhl is part of the district of Kaiserslautern, in the Rhineland-Palatinate. The population is only around 8,000 but it has also been the birthplace of two twenty-first century baseball players: Mets pitcher Tobi Stoner, whose five-game career began in 2009, and outfielder Aaron Altherr, who began his career with six seasons in a Phillies uniform starting in 2014.

They are just three of 42 German-born major-league baseball players, ranking Germany 10 th in the number of major leaguers born in a given country other than the United States. The United States ranks first, followed by (through the year 2021): Dominican Republic (830), Venezuela (438), Cuba (378), Canada (258), Mexico (139), Panama (77), Japan (72), United Kingdom (50), Ireland (47), and Germany (42). There have been 297 natives of Puerto Rico who have played major-league baseball, but Puerto Rico is part of the United States.

Former NBA center Shawn Bradley and former NFL players Reggie Williams, Willie Blade, and Rob Awalt all were born in Landstuhl, as well as actor LeVar Burton, who played Tigers All-Star Ron LeFlore in the 1978 made-for-TV movie, “One in a Million: The Ron LeFlore Story”.

2 A third major leaguer named Tom McCarthy had played outfield for two Boston major-league teams in the nineteenth century, most notably for the Beaneaters from 1892-95. That Tom McCarthy, generally known as Tommy, was voted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1946.

3 “Tom McCarthy, Plymouth-Carver,” Boston Globe, June 19, 1979: 36.

4 Peter Gammons, “Sox eye a fresh reliever,” Boston Globe, February 25, 1985: 29, 32.

5 Bill Slack was a local legend in Winston-Salem, having managed the Red Sox Single-A farm club (through two different team names) for 12 ½ seasons in five different stints between 1963 and 1984. In all five stints, he led the team to at least one Carolina League finals series, and in all but the last stint, his teams won at least one league title. Slack was named as the manager on the Carolina League all-time all-star team in 1995, and in 2002 he was named to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. Dan Collins, “Legacy: Slack’s influence on local baseball remains strong,” Winston-Salem Journal, June 16, 2008 (https://journalnow.com/sports/legacy-slacks-influence-on-local-baseball-remains-strong/article_743587ee-ad5f-557f-be99-aa0d3c2acac8.html) Accessed January 17, 2022).

6 Peter Gammons, “Sox eye a fresh reliever.”

7 Peter Gammons, “Red Sox farm system had crop still growing,” Boston Globe, September 8, 1984: 27.

8 Peter Gammons, “The search is on,” Boston Globe, February 25, 1985: 32.

9 Peter Gammons, “Sox eye a fresh reliever.”

10 Larry Whiteside, “McCarthy hoping for some fireworks,” Boston Globe, July 5, 1985: 27.

11 Whiteside.

12 Joe Giuliotti, “Crawford Set for Return,” Boston Herald, July 7, 1985: 5.

13 Dave Van Dyke, “Fisk Tells Chisox to Serve Youth,” The Sporting News, July 17, 1989: 20.

14 “Briefs,” Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1989: E2.

15 “Fast Gainer Perez Takes Off 10 Pounds,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1990: 15.

16 Bob Nightengale, “Dodgers Name Their Opening Day Starter,” Los Angeles Times, March 21, 1995: OCC4.

17 Bob Nightengale, “Players Leave Camp, But Claire Plans to Return,” Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1995: C2.

18 In fact, a remarkable 39 eventual major leaguers spent time playing for that 1995 Dukes team.

Full Name

Thomas Michael McCarthy

Born

June 18, 1961 at Landstuhl, (Germany)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.