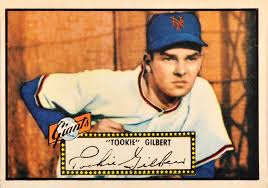

Tookie Gilbert

Tookie Gilbert’s baseball career started out in classical “boy wonder” fashion. Coming from a family with strong baseball bloodlines, he was a two-sport all-star in high school in the mid-1940s. He was heavily recruited by five major-league teams, ultimately signing with the New York Giants for a hefty $50,000 bonus. His father used a lottery to select the Giants. He appeared to be on track to fulfill the expectations of his boyhood stardom when he excelled at the minor-league level before making his major-league debut with the Giants in 1950. Yet after two unspectacular seasons in the majors, he suddenly decided to walk away from the game at age 24.

Tookie Gilbert’s baseball career started out in classical “boy wonder” fashion. Coming from a family with strong baseball bloodlines, he was a two-sport all-star in high school in the mid-1940s. He was heavily recruited by five major-league teams, ultimately signing with the New York Giants for a hefty $50,000 bonus. His father used a lottery to select the Giants. He appeared to be on track to fulfill the expectations of his boyhood stardom when he excelled at the minor-league level before making his major-league debut with the Giants in 1950. Yet after two unspectacular seasons in the majors, he suddenly decided to walk away from the game at age 24.

Harold Joseph “Tookie” Gilbert had his first expectation of being a ballplayer set on April 4, 1929, the day he was born in New Orleans. His father Larry Gilbert Sr., player-manager of the minor-league New Orleans Pelicans, jokingly agreed to give owner A. J. Heinemann an option to sign his son to a contract with the hometown team.1 Tookie was the third son of Larry and Gertrude (née Mader) Gilbert. His older brothers, Larry Jr. and Charlie, also had careers in professional baseball.2 He got his nickname as a child when his brothers frequently referred to him as “rookie,” which he mispronounced as “tookie.”3

Larry Sr. was also born in New Orleans, starting his career in 1910 as an 18-year-old minor-leaguer. He played two seasons with the Boston Braves, including the 1914 season when the “Miracle Braves” won the National League pennant after being 15 games out of first place on July 4. A subpar season with the Braves in 1915 led to a demotion to Toronto at mid-season. After a minor-league season in 1916, he decided to continue his career in his hometown in 1917.

Larry Sr. became a legendary figure in the Southern Association, continuing to play for the Pelicans until 1925. He also held managerial duties from 1923 to 1938, except for 1932 when he served as president, while also holding a partial ownership stake. He left New Orleans for Nashville in 1939, where he managed until 1948. Altogether he won 11 championships in the league, including six straight with Nashville. The extensive network he developed within the baseball community became a key factor in how Tookie got into professional baseball.

Tookie wore his first uniform in Pelican Stadium as a three-year-old mascot and later as a batboy for his father’s Pelicans team.4 He came into his own as a sophomore first baseman for Jesuit High School in 1944, honored with a selection to the All-Prep team named by the Times-Picayune. The Blue Jays won the state crown the next season, as Tookie again garnered all-star honors and was designated the league’s most valuable player. He was selected by a panel of coaches to represent Louisiana in Esquire magazine’s All-American game at New York’s Polo Grounds. However, he opted out of appearing in the prestigious event because he wanted to play for his American Legion team that had advanced past the state tournament.5 His amateur success sparked rumors that the 16-year-old phenom had received an offer of $40,000 to sign with the New York Yankees once he was graduated from high school.6

In his senior schoolyear in 1946, Tookie was an all-star forward on the Jesuit basketball team that won the state championship. He repeated as the city prep baseball league’s most valuable player.7

With his father’s influence and the fact his brothers had preceded him in professional baseball, it seemed only natural that Tookie would also pursue a pro career. His accomplishments gained him attention from numerous major-league scouts.

In early June 1946 the Times-Picayune surmised that Tookie was likely headed to the Chicago Cubs, based on Larry Sr.’s Nashville team affiliation with Chicago.8 However, Tookie had a number of other serious major-league suitors who lobbied Larry Sr. to allow his son to sign with them. Unlike most other prospects who sign immediately following their graduation from high school, Tookie continued to play amateur baseball during the summer with the Jesuit-based, city title-winning American Legion team. He also participated in two all-star tournaments. He gained national attention when he was selected again to represent Louisiana in the Esquire All-American contest in Chicago’s Wrigley Field. This time he decided to attend the event. He passed up an opportunity to play in postseason competition with his Legion team, which ultimately won the national championship. 9

In the meantime, Larry Sr. had become inundated by contacts from the various major-league suitors, including several with which he had personal relationships. He ultimately decided to hold a lottery on October 13 to decide which team would gain the rights to sign Tookie. He explained his rationale for his approach by saying, “I didn’t want to start a bidding contest for the boy’s services. I decided to set a price (amount undisclosed) and notify my friends to come down and participate in the picking.”10

The event occurred at a room in the Monteleone Hotel in downtown New Orleans. Tookie’s father held a hat containing the names of five teams: New York Giants, New York Yankees, Boston Red Sox, Boston Braves, and Pittsburgh Pirates. His mother drew the name of the New York Giants. Giants player-manager and New Orleans resident Mel Ott, attending the event in person, was elated. “I’m glad we got Tookie,” Ott said. “I have been trying for four years to get Larry’s consent to let him play with the Giants. As far back as 1942 Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert were in New York to witness the World Series and it was at breakfast one morning in that year that I first suggested that we sign him up.” Tookie and his parents were relieved the recruiting ordeal had been settled after many months of deliberation.11

The Giants shelled out Larry Sr.’s requirement of $50,000 for the 17-year-old’s signing bonus, which at that time was a premium payout. By comparison, New Orleans schoolboy phenom Dick Callahan signed for $15,000 in 1944 with the Red Sox, while Tookie’s former Jesuit teammate Putsy Caballero was paid a $10,000 bonus by the Phillies to go straight into the majors near the end of the 1944 season. Tookie’s generous haul was comparable to Dick Wakefield’s securing one of the first significant bonuses in the majors when he signed for $52,000 out of the University of Michigan in 1941.

Perhaps to justify their hefty investment in the amateur slugging sensation, the Giants started Tookie’s pro career in 1947 with Triple-A affiliate Minneapolis, overriding his father’s suggestion that Tookie begin at a lower level. Tookie quickly became overmatched at Minneapolis (three hits in 32 plate appearances) and after 16 games was sent to Erie in the Class C Mid Atlantic League. Upon his son’s demotion, Larry Sr. said, “I had asked, even before the season started, that Tookie be allowed to play with a smaller club and I’m surely glad they have sent him out. It will do him good to be in a league where he can play every game and where he is playing against boys of his own age and experience.”12 His father proved to be correct in his advice, as Tookie batted .333 with 11 HRs in 92 games with Erie.

Tookie showed a nice progression in 1948 with Class A Sioux City, as he continued to demonstrate power with 26 HRs while still maintaining a .299 batting average. He led the Western League with 114 RBIs. Also that summer, on July 14, he got married to Jean Adams. He flew back home to New Orleans (Jean’s native city too), where the wedding took place at Sacred Heart Catholic Church.13

Tookie began spring training in 1949 with Minneapolis but did not deliver up to expectations in exhibition games. Giants farm director Carl Hubbell worked out an arrangement to option him to Nashville, where his father was then a part owner and general manager of the Cubs affiliate. The Giants did not have a Double-A farm club at the time; and since they did not think Tookie was ready for Minneapolis, they hesitated to send him back to the Class A level.14 A Giants spokesman said, “We believe one season under Larry’s wing in Nashville will be the best possible thing for Tookie.” He added, “He’s a great ballplayer. Within a year or two he should be one of the best young first basemen in the game.” When Tookie originally signed his pro contract, Larry Sr. had hoped his son could spend one year with him on his way to the big-leagues. 15 His father’s wish came to fruition.

Nashville boasted a potent offense under its new manager, Rollie Hemsley, and Tookie was one of its main contributors along with Carl Sawatski, Babe Barna, and Bob Borkowski. In late July, the foursome occupied four of the top five spots in in the Southern Association batting title race.16 One of Tookie’s best games involved a 13-inning affair against Memphis on July 6 when he slammed three home runs. New Orleans sportswriter William O’Keefe, who had followed Tookie’s career since high school, had glowing compliments for the young star, “Young Gilbert has everything—the physique, baseball knowledge and efficiency.” He added, “Gilbert’s stance and swing at the plate are a picture of grace and power. The boy has the fighting spirit and desire to win that his daddy had.”17

The Vols won the Southern Association championship, with Tookie leading the league in hits (197) and runs (146). He slammed 33 home runs en route to batting .334. He was named to the league’s all-star team. Still only 20 years old, he appeared to be on a path to fulfill the major-league expectations established for him at his historic signing.

Tookie returned to the Giants farm system with Minneapolis in 1950, but after only six games he was called up to the Giants to replace first baseman Jack Harshman, who was sent down to the minors. The Giants had expected Tookie to get more seasoning at the higher minor-league level before bringing him up.18 However, the big club’s season did not start out well (2-7), and the team looked for someone to provide a much-needed boost.

The highly-touted six-foot-two, 185-pound rookie embarked on the major-league career everyone had anticipated since he was a teenager in New Orleans. He had an auspicious debut at the Polo Grounds on May 5 against Pittsburgh. He got a base hit in his second at-bat and followed with a three-run homer in the eighth inning off Mel Queen.

Tookie took a practical attitude about his call-up. He said, “You know, everybody keeps telling me how tough the pressure is on me and what a big spot I’m in. I can’t look it at that way. To me it’s just a tremendous opportunity, one that only a few kids get, and I’m just going to try and do my best to make good on it. Maybe the pressure is there, but if a guy can’t face that he isn’t cut out to be a major leaguer.”19 However, the immediate lift Tookie provided the Giants upon his arrival was short-lived.

The left-handed hitter (but right-handed fielder) soon learned more about the pressure of hitting against big-league pitching. His debut game turned out to be his best in 113 games. His power stroke from the minors did not carry over into his rookie season, as he managed to hit only four home runs in 370 plate appearances.

After sitting in the second division through August, Giants manager Leo Durocher eventually got the team headed in the right direction late in the season. Unfortunately for Tookie, he was not a factor in their turnaround. His playing time was primarily limited to defensive replacement opportunities after July, as he gave way to outfielder Monte Irvin, redeployed as the first sacker by Durocher. The Giants finished the season in third place, five games behind league leader Philadelphia. Tookie’s final .220 batting average and low home run output raised questions about his ability to hit major-league pitching. But the Giants were willing to be patient with the 21-year-old, since they acknowledged he had been rushed to the majors.

At a time when some ballplayers were being called into military service during the Korean conflict, Tookie received a 3-A classification by the draft board because he was married.20

At the start of spring training in 1951, Tookie reflected on his rookie season, “No, don’t blame the pressure on my lousy year at bat. Sure, I was called up quickly and put right in there, but I didn’t feel any particular pressure. I just wasn’t hitting, that all. No, I don’t think all the southpaws made much difference.”21

When Tookie didn’t show improvement in training camp, he was optioned to Minneapolis. Durocher said Tookie confided that he was happy to be going to the Millers, where he could play regularly. Durocher said, “Tookie told me he was going to shorten his stride and get back to hitting the same way he was last year. That’s all he has to do. It’s like a fellow getting his golf swing straightened out.”22

Tookie was also open to going to Oakland in the Pacific Coast League. There, he could play under the tutelage of Oaks manager and old friend, Mel Ott.23 In New York, Irvin started the Giants’ season as the starter at first base but eventually switched positions with outfielder Whitey Lockman. For the next five seasons after the move, Lockman became a fixture at first base. His ascent would eventually play a part in Tookie’s fate in baseball.

Tookie returned to his prior minor-league hitting form in Minneapolis. He led the American Association with 29 home runs and drove in 100 runs, while posting an impressive .384 on-base percentage that included 86 walks.

There was discussion among Giants personnel to promote Tookie to the big-league club in 1952 and return Lockman to the outfield. Lockman wasn’t in favor of the proposed move. He said, “Leo [Durocher] said I could have the [first baseman’s] job and I want it.”.24 With Nashville as a Giants affiliate, Tookie’s father, then owner of the Vols, squelched any idea of Tookie playing for the Vols again. He said he didn’t see any advantage to Tookie’s development by reverting to a lower level.25

The Giants decided to option him to Oakland (an unaffiliated franchise) instead, with the understanding he was subject to 24-hour recall. Giants owner Horace Stoneham reportedly responded to an urgent request from long-time friend, Oakland owner Brick Laws, to fill a shortage of players at first base and shortstop. In addition to Tookie, Rudy Rufer was sent over as the shortstop, although he turned out be unproductive and was returned. Additional optioned Giants players followed, including catcher Ray Noble. Tookie had lost some of his luster with Durocher after his disappointing 1950 season; and since the Giants skipper was happy with Lockman as his first baseman, he didn’t stand in the way of shipping Tookie to Oakland.26

Oakland was still being managed by Ott and touted as the pre-season favorite to win the Pacific Coast League. Early in the season Tookie faced the possibility of rejoining the Giants when Monte Irvin broke his leg and Willie Mays was due to join the army. But he was somewhat relieved when the Giants acquired Bob Elliott instead, since he preferred to play full-time in Oakland under Ott’s oversight versus being a part-time player with the Giants.27

After a slow start, Tookie led the PCL in home runs and RBIs through much of the season. He finished with a league-leading 118 RBIs, while his 31 HRs were second only to leader Max West’s 35. His slugging and Noble’s play as catcher kept the Oaks in the pennant chase, but they wound up in second place, five games behind Hollywood.

For the second straight season, Tookie had good command of his hitting at the Triple-A level. It seemed he had regained the confidence which had been shaken with his rushed call-up in 1950. He rationalized that he had tried too hard after not being initially ready to play at the major-league level. He admitted, “It was a big thrill for me, but I don’t think it was worth it.”28

Tookie’s latest performance at Oakland required Durocher to think hard about what to do with him for the 1953 season. The skipper could use an extra bat coming off the bench and an occasional alternative for Lockman. During those instances, Lockman could be used in the outfield. Tookie’s name was also being tossed about as trade bait. Adding to that possibility, Larry Sr. (then affiliated with the Giants through the Nashville franchise) encouraged Giants ownership to trade Tookie to a team where he could play full-time.29

Tookie made the Giants’ decision about his disposition even more difficult during spring training. He made a favorable impression with a .353 average in 17 exhibition games and 34 at-bats. His slugging included eight extra-base hits and 11 RBIs.30 He displayed the type of hitting the Giants had always hoped he would provide at the major-league level.

The Giants decided to break camp with Tookie on their big-league roster. During the first four weeks of the regular season, he was hitless in an occasional pinch-hitter role. With center fielder Willie Mays still serving in the army, Durocher shifted Lockman to the outfield by mid-May, giving Tookie another opportunity as the full-time first baseman. There was optimism when one of his first starts saw him go 4-for-5 with a homer and 4 RBIs. However, aside from that outing, he was practically in a slump between May 15 and June 27, posting a .210 average with 3 HRs and 12 RBIs.

Lockman reclaimed his old job at first by the end of June, relegating Tookie to minor pinch-hitting and defensive replacement roles. During his final 33 games of the season, including 10 starts, he batted just .115 with four RBIs. With his disappointing season, it seemed likely that Tookie would be destined for a new team in 1954.

On February 13, 1954, Tookie surprised everyone with his announcement to quit baseball. The 24-year-old decided he wanted to pursue a full-time career in a paint business in New Orleans. Already with two children and another on the way, he figured he needed to take care of his family without the burden of being away from home a good part of each year. He said, “This wasn’t an easy decision for me, but I’ve made up my mind that baseball is just too funny to depend on. I’ve got to look ahead, to grab something stable with a secure future, and I might as well start now.”31

He summed up his retirement, “Well, I found myself standing still and so I decided I owed it to my wife and kids to try something else while I was young. And that’s why I quit baseball.”32 Had he stayed in baseball, Giants vice president Chub Feeney would have targeted him for Minneapolis for the 1954 season, since Bobby Hofman had emerged as the backup for Lockman on the Giants roster. However, Feeney said he had not planned to cut Tookie’s salary.33 In any case, in Tookie’s mind, going back to Minneapolis was equivalent to “standing still.”

Some baseball insiders surmised that Tookie planned to use the retirement announcement as leverage to obtain a trade to another team. He answered this implication by saying, “I guess some folks will think this is just a stall; that I’m fishing for a trade that will prompt me to go back. But I give you my word I’ve figured it all out and I see much more security in my present job than I do in baseball. The managerial end of it never appealed to me, after seeing what my dad went through. He worshipped baseball; I loved it but I haven’t come to worship it.”34

A month later, Larry Sr. stated he thought Tookie would reconsider his retirement and return to the Giants. He said, “Frankly, I want him to play. As for his big league future, I’m not giving up on him. After all, he’s only 24.”35

Tookie’s career results raised questions about whether high bonuses paid to teenage prospects were good investments for owners. He wasn’t alone in how his pro career had become a disappointment. For example, New Orleanian teenagers Dick Callahan and Putsy Caballero, who had preceded Tookie with substantial bonuses, wound up not delivering corresponding substantial careers. Paul Pettit and Frank House, both of whom signed a few years after Tookie with record-setting bonuses, also fell short of expectations. In an editorial shortly after Tookie’s retirement announcement, The Sporting News took the position that “the system of bonuses is not only bad for baseball, but also for the boys who collect the loot.”36

Tookie was active in local New Orleans baseball activities, including playing in the Sugar Cane Semi-Pro League, participating in annual charity baseball games which featured former professional players, and playing in city softball leagues.

When the New Orleans minor-league franchise struggled in the late 1950s, city officials and local baseball figures came together to identify ways in which the team could improve attendance and ultimately its financial viability during the 1959 season. In addition to selected ballpark improvements, former major-league players living in New Orleans were approached by Mayor Chep Morrison about coming out of retirement to play for the Pelicans.37 Former Red Sox all-star pitcher Mel Parnell was brought in to manage the club. Major-league veteran Jack Kramer came out of retirement at age 41 to pitch in a handful of games, while Tookie joined the team to play first base. At 30 years of age, he led the team with 22 homers and 80 RBIs. The added veterans didn’t help much, as the Pelicans finished sixth in the league and disbanded after the season.

Tookie was in private business as a realtor when his friends and business associates urged him to enter politics. He decided to run as an independent for the civil sheriff position in Orleans Parish in New Orleans and was elected to terms beginning in 1962 and 1966. His life was cut short at age 38 on June 23, 1967, when he died from a heart attack while driving his car. He had previously suffered a heart attack in March 1963. Tookie was survived by his wife, Jean; two sons, Harold J. Jr. and Glenn Gilbert; and daughter Donna Gilbert.38

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by William Lamb.

Sources

In addition to the sources in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and the following:

“Gilbert Picked for Game,” Times-Picayune, July 3, 1945: 13.

“Tookie Gilbert Called Up by Giants; To See Action Tonight,” Times-Picayune, June 5, 1950: 36.

Antunovich, Jack. “Jesuit Jays Dominate Prep League All-Star Ball Squad,” Times-Picayune, May 27, 1945: 18.

Antunovich, Jack. “Tookie Gilbert Chosen for All-America Game,” Times-Picayune, June 3, 1946: 16.

Drebinger, John. “Pittsburgh Victor, 5-4, Before 31,785,” New York Times, June 5, 1950: L-10.

Hart, Carol. “1944 All-Prep Baseball Team Led by Callahan and Azzarello,” Times-Picayune, May 21, 1944: 24.

Johnson, Lloyd and Wolff, Miles, eds. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball Third Edition, (Durham, NC: Baseball America, 2007).

Myers, Bob. “Gilbert Fine Player, But Unable to Replace Lockman,” Times-Picayune, May 15, 1953: 6,3.

Wicker, Charles. “Champion Jesuit Jays Place Three Men on All-Prep Quintet,” Times-Picayune, March 10, 1946: 28.

Notes

1 William Keefe, “Brooklyn Comes to Play Cleveland While Pels Hit Road,” Times-Picayune, April 5, 1929: 20.

2 Larry Jr. and Charlie Gilbert preceded Tookie as standout baseball players at Jesuit High School in New Orleans. Larry Jr. played in the minors in 1937 and 1938, including one season on his father’s New Orleans Pelicans team. His career was cut short due to a heart ailment. Charlie played six seasons in the majors from 1940 to 1947 for the Dodgers, Cubs, and Phillies. He played three seasons for Nashville when his father was manager.

3 “Acorn Album,” Oakland Tribune, June 27, 1952: 30.

4 Fred Russell, “Bonus Kid Tookie Gilbert ‘Retiring’ as Player at 24,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1954: 13.

5 “Mace Will Play in Boys’ Contest,” Times-Picayune, August 9, 1945: 15.

6 William Keefe, “Say $40,000 Bid for Gilbert,” Times-Picayune, July 28, 1945: 7. (Author’s note: This rumor may well have had credibility, since major-league teams were offering contracts to high-school prep stars due to a shortage of players during World War II. Joe Nuxhall and Putsy Caballero were examples of such amateur players.)

7 Jack Antunovich, “Six Jays on All-Prep ‘9’,” Times-Picayune, June 9, 1946: 26.

8 William Keefe, “Riot Scene Averted,” Times-Picayune, June 5, 1946: 14.

9 Charles Wicker, “Legion World Series Set for New Orleans If Jays Win Sectional,” Times-Picayune, August 16, 1946:16.

10 Eddie Pagnac, “Mel Ott Signs Tookie Gilbert to New York Giant Contract,” Times-Picayune, October 16, 1946: 15.

11 Pagnac.

12 William Keefe, “’Tookie’ Crashes In,” Times-Picayune, June 26, 1947: 16.

13 “He’s Bridegroom Now,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, July 15, 1948: 17.

14 Fred Russell, “Sidelines,” Nashville Banner, March 26, 1949: 6.

15 Fred Russell, “Tookie Gilbert to Play for Vols,” Nashville Banner, March 25, 1949: 38.

16 “Sawatski, Barna, Borkowski, Gilbert Form Batting Monopoly,” Times-Picayune, July 24, 1949: 5.

17 William Keefe, “Tookie Gilbert a Natural,” Times-Picayune, July 10, 1949: 24.

18 Arthur Daley, “Lookie, Lookie, Here Comes Tookie,” New York Times, May 28, 1950: 28.

19 Arch Murray, “Young Gilbert Gallops to Aid of Giants,” The Sporting News, May 17, 1950: 3.

20 Tribune Wire Services, Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 30, 1950: 15.

21 Halsey Hall, “New Durocher? ‘Nope, Just a New Man,’ Leo Tells Hall,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, March 5, 1951: 20.

22 Fred Russell, “Tookie Gave Club a Lift,” Nashville Banner, March 23, 1951: 32.

23 Fred Russell, “Seasoning for Tookie,” Nashville Banner, March 15, 1951: 28.

24 “They Say in Sports,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, January 26, 1952: 12.

25 Fred Russell, “Will Tookie Return?” Nashville Banner, February 21, 1952: 33.

26 Arch Murray, “Tough Problem for Durocher,” Nashville Banner, December 24, 1952: 24.

27 Emmons Byrne, “The Bull Pen,” Oakland Tribune, April 10, 1952: 27.

28 Murray, 1952.

29 “Giants Willing to Trade Tookie,” Nashville Banner, March 17, 1953: 17.

30 Bill Roberts, “Gilbert Hitting at .353 Clip in Giants’ Spring Games,” Nashville Banner, April 8, 1953: 25.

31 Fred Russell, “Bonus Kid Tookie Gilbert ‘Retiring’ As a Player at 24,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1954: 13.

32 Bill Keefe, “A Lot of Bitterness Mixed With Sweet, Says Tookie,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1954: 13.

33 “Giants Had Planned to Send Tookie to Minneapolis Club,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1954: 13.

34 Keefe, 1954.

35 “Tookie Gilbert ‘Will Likely Rejoin Giants,’ His Dad Says,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1954: 32.

36 “Bonus Risks Again Spotlighted,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1954: 10.

37 Bob Roesler, “Baseball Figures Ponder Pel Problems,” Times-Picayune, December 20, 1958: 27.

38 “Death Claims Tookie Gilbert,” Times-Picayune, June 24, 1967: 1.

Full Name

Harold Joseph Gilbert

Born

April 4, 1929 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

June 23, 1967 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.