Boston Braves team ownership history

This article was written by Bob LeMoine

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

The baseball team known as the Braves makes its home in Atlanta, but traces its diamond ancestry back through Milwaukee and to Boston, where it began in 1871. In fact, the Atlanta Braves are the only baseball team that has played every season consecutively since 1871, outdating even the National League itself. While forgotten by most fans today, the Boston National League club was a dominating force in the early years of professional baseball. This is the story of the business leaders who made the Boston team alive and thrive in an era where teams folded due to lack of local support and finances. It all began with a dream of a Boston businessman in 1871.

The baseball team known as the Braves makes its home in Atlanta, but traces its diamond ancestry back through Milwaukee and to Boston, where it began in 1871. In fact, the Atlanta Braves are the only baseball team that has played every season consecutively since 1871, outdating even the National League itself. While forgotten by most fans today, the Boston National League club was a dominating force in the early years of professional baseball. This is the story of the business leaders who made the Boston team alive and thrive in an era where teams folded due to lack of local support and finances. It all began with a dream of a Boston businessman in 1871.

Ivers W. Adams was a clerk at John H. Pray, Sons & Company in Boston, “part of the emerging white-collar middle class that filled the void between the rich and poor social classes.”1 He was building up his wealth, and would not need to work beyond the age of 44, retiring in 1882.2 He had seen George Wright and his brother Harry of the Cincinnati Red Stockings come to town with their gleaming red uniforms and sparkling play in the field. Adams would pass Boston Common, where local amateur clubs like the Lowell team played, as he caught the train for home. He may have seen the Red Stockings playing Lowell on June 10, 1869. The Red Stockings, baseball’s first openly professional team, toured coast-to-coast, going undefeated against every team they faced from 1869 through the middle of June 1870. The best local talent in the Boston area, on the best amateur teams the city could produce, was simply no match. Adams, though, had plans. What if these fantastic Wright brothers would come east? Boston could certainly support a professional squad; the crowds that turned out for these Red Stockings proved it, and Adams knew several people of means who would put the money down to make a Boston team a reality.

The Red Stockings eventually lost, and their backers in Cincinnati decided a team that lost now and then was not worth the investment. This was now Adams’s chance. He convinced the Wrights that Boston would welcome them with open arms and wallets. While baseball in Boston dated to at least 1854 with amateur games played on the Common,3 several factors had made the city the only major urban area in the Northeast without a serious baseball team. For one, it took time for the “New England Game” version of baseball (which included a smaller diamond and distance from home plate to the pitcher’s box, more players on the field, and outs being recorded by “soaking,” or plunking a runner with the ball) to give way to the more prevalent “New York Game.”4 Another factor was the lack of an adequate playing field, which was solved when the Union Grounds were built in 1869 in Boston’s South End. (The ballpark was later called the South End Grounds.) And besides these, people with big pockets were needed to fund a professional team, and Adams was the one with connections to do so.

Harry Wright already knew how to assemble a new team. He brought his brother George, Charlie Gould, and Cal McVey from Cincinnati, Dave Birdsall from the Union Club of Morrisania, Harry Schafer from the Philadelphia Athletics, and Al Spalding, Ross Barnes, and Fred Cone from the Rockford, Illinois, team. Harry found the players, Adams found the bucks.

The Massachusetts Legislature incorporated the team with $15,000 capital, made possible by several prominent businessmen.5 Adams met these fellow Boston-area entrepreneurs at Boston’s Parker House, on January 20, 1871. Adams emphasized to them that these Wright brothers “were the only two men possessing the knowledge and the ability to manage and discipline a nine … and whose honesty and integrity I could place implicit confidence.”6 Two hundred tickets of membership sold to interested people, granting them free admission to games all season long as well as use of the clubhouse.7 Evidently, these tickets of membership were not stock in the corporation, but more like season tickets along with membership in a somewhat exclusive fan club. According to newspaper accounts two years later, the team had 25 shareholders who’d agreed to pay the $100 face value of the 150 shares of stock. However, the purchase price was more of a pledge than an actual payment. When necessary, the stockholders could be called on to pay further assessments on their pledge up to the face value of the stock.8

“Boston can now boast of possessing a first-class professional Base Ball Club,” declared the Boston Journal, “as all the efforts tending to establish an institution of this kind here culminated yesterday.”9

The next step involved joining a league of professional teams, a move that had been on the horizon as amateur and professional baseball teams were parting ways. The 1870 fall meeting of the National Association of Base Ball Players had been “a fiery affair marked by hot words between the two camps, and it ended with the amateurs staging a walkout.”10 It was clear that baseball would be expanding from the world of fun and recreation to fun, recreation, and business. Possessing the vision of a new professional league but little time to properly organize and hammer out specifics, these new pioneers quickly created a new league, and on March 17, 1871, “‘The National Association of Professional Base Ball Players’ thereby sprang into existence.”11

The 1871 season saw Boston (20-10) finish a close third in the National Association’s inaugural season as Barnes, McVey, and George Wright batted over .400, although an injury to Wright early in the season cost the Red Stockings some wins that would have decided the pennant.

At a meeting on December 7, 1871, the Boston Base Ball Association was officially incorporated. A treasurer’s report was given, but sadly the details are lost to history. “We have not allowed the sale of intoxicating drinks upon our grounds, and that other attendant evil, betting, has been strictly prohibited,” Adams told the meeting. “These provisions, we believe, have assisted in drawing the better class of our people to witness the many exciting contests which have taken place from time to time.”12

“If we have been instrumental in elevating the standard of our national pastime,” Adams continued, “to the accomplishment of which object we have turned our special attention, then we have cause for satisfaction. … We look forward to the coming season with confidence.”13 Adams was unanimously re-elected, but declined, a second term as president. John A. Conkey was elected in his place. Conkey was a clerk for Tuckerman-Townsend, noted tea merchants. He later became a customs broker, forwarder, estate trustee, and bank notary.14

The 1872 season saw Boston win its first pennant, as Spalding went 38-8 with a 1.85 ERA and Barnes batted .430. While they dominated on the field, however, the Red Stockings were failing financially, so much so that there was doubt whether the pennant-winning team would continue in 1873. As the Herald reported, “The close of the base ball season of 1872 finds the Boston club in a crippled financial condition,” with debt in the area of $4,000-$5,000.15 While reports of the amount of debt differed, there was a general consensus that the team was losing money. The New York Clipper blamed “an error in the management of its affairs during the closing part of the season,” when the team scheduled a poorly conceived tournament that drew small crowds, and “sundry exhibition contests” that failed to profit the team much of anything.16 There were unpaid salaries to some players. There was the Great Fire that swept through Boston in November 1872. Some players lost homes and possessions, By December, Spalding himself was owed $800 and got an offseason job at the New York Graphic.17

But Harry Wright was determined that the team would continue.18 Covering the club’s annual meeting on December 4, 1872, at the Parker House, the local papers reported slightly different income numbers, which makes it hard to clarify the exact situation.19 The Globe said the 1871 debt alone was $7,000 and for 1872 was $716. The Herald said the current debt was $4,000. The Journal reported that the season of 1872 brought in $18,700 income, but this was $4,000 less than the club’s costs, which arose from the leasing of the Union Grounds and “about $3,000 of unpaid assessments on the capital stock.”

None of these numbers looked good. The 25 stockholders had “subscribed in the fond belief that at the worse no more than fifty per cent of the amount would ever be called for.” However, the stockholders had been called upon in 1871 to meet the $7,000 deficit and were being tapped again for the 1872 deficit, so “some of the stockholders refuse to pay their assessments and signify their willingness to throw up their stock. The cause for this unpleasant state of things was thought to be mainly due to the large salaries paid.” Players, they said, “must entertain more moderate notions of compensation … and it is probable that $1,800 salaries will be less frequent than heretofore.”

In addition to soliciting existing stockholders and cutting salaries, those at the meeting decided to seek additional investors. More broadly, “a committee of five was chosen to report at a future meeting a plan or plans for assisting in paying off the debt … and also for raising a (guaranty) for carrying on the club next season.”20

Charles H. Porter was elected president, succeeding Conkey. Porter was a Civil War veteran who later became the first mayor of Quincy, Massachusetts. He had organized the Quincy Actives Base Ball Team and served as Quincy park commissioner. He also served terms on the city school board and fire department, and formed the Quincy Water Company.21

A week later, at Boston’s Brackett’s Hall, a meeting was held to hear the report of the five-man committee. A brand-new organization called the Boston Base Ball Club was formed and would inherit the debt of the Boston Base Ball Association, now reported as $2,700, as well as a majority of its stock. The Club would serve as a “booster club” and infuse money into the association.22 “A year’s lease of its buildings and grounds and its charter, as well as the purchase of the majority of stock would, by the proposed plan, “give to the new club control of the affairs of the (Boston Base Ball Association), without involving the members of the new (Boston Baseball Club) in the debts of the association,” wrote the Globe.23 The report was accepted, and over 40 new members were reported. All members paid a $15 initiation and $10 yearly dues, which gave them a season ticket to the games and a say in the control of stock. Players who were owed money would be repaid in installments, and a recommendation was made that “the players be handsomely remembered in case a surplus of funds existed.”24 The new constitution was adopted on December 14.25 Another meeting, on January 2, 1873, in which the pennant was hung on the wall, saw the number of new members rise to 100.26

The 1873 season was another success on the field, as Boston won a second straight pennant. Spalding went 41-14 and six starters batted .325 or better. Financially, the team was on more solid footing as well. At the annual meeting in December at Boston’s Hampshire Hall, the membership was listed at 108, and $2,730 was collected from membership fees. Numbers vary, but the Boston Traveler listed profits around $4,245.63, while the Daily Advertiser listed profits (actually probably income) near $27,832 and expenses at $27,200. Whatever the exact numbers, the team was able to pay off the debts from previous years and still have $767.93 in the bank.27 Nicholas T. Apollonio was elected president for the coming year. The son of an Italian immigrant (perhaps the first such associated with professional baseball), Apollonio was an accountant and clerk who directed operations for the Great Falls Manufacturing Co. for 35 years. He later became involved with the Winchester Savings Bank.28

The 1873 season was another success on the field, as Boston won a second straight pennant. Spalding went 41-14 and six starters batted .325 or better. Financially, the team was on more solid footing as well. At the annual meeting in December at Boston’s Hampshire Hall, the membership was listed at 108, and $2,730 was collected from membership fees. Numbers vary, but the Boston Traveler listed profits around $4,245.63, while the Daily Advertiser listed profits (actually probably income) near $27,832 and expenses at $27,200. Whatever the exact numbers, the team was able to pay off the debts from previous years and still have $767.93 in the bank.27 Nicholas T. Apollonio was elected president for the coming year. The son of an Italian immigrant (perhaps the first such associated with professional baseball), Apollonio was an accountant and clerk who directed operations for the Great Falls Manufacturing Co. for 35 years. He later became involved with the Winchester Savings Bank.28

The 1874 season included a losing endeavor to make money on a trip to bring baseball to England. With 74 renewals of membership the team raised $739 from current members and $845 from 34 new members.29 The Frederick E. Long Papers at the Baseball Hall of Fame list Boston’s total revenue at $31,699.10 and expenses of $30,865.97. The trip overseas cost $2,318.13 and brought in $1,660.69.30 Still, Boston won another pennant, and was in the black financially. It was reported C.C. Adams became president over Apollonio, but Apollonio was still mentioned being president throughout the year, so it is uncertain who exactly was president in 1875, or if both served.

The 1875 season was Boston’s most dominating season (71-8), as it won its fourth pennant in a row, but it proved the final season of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players. Spalding, Barnes, McVey, and Deacon White left for Chicago, whose owner, William Hulbert, opened his wallet, the only way the Red Stockings could be defeated. Income for the year was reported as $37,787.06 and expenses $34,525.99.31 While it would be an oft-repeated business move to sign players from other teams, this was the first such outright defection in baseball history. There was talk at the winter convention in March 1876 of expelling the defecting Boston players from the league.32 But before there was a chance that this could happen, Hulbert and Spalding drafted the constitution for a new National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs. The structure of professional baseball was changing. The National Association’s five-year run was a player-driven endeavor; now, power would be in the hands of the owners. Harry Wright, sensing Hulbert’s business sense, went along with the new league, as did other clubs. The National League was born, and a new chapter in baseball history had begun. Because of the loss of its stars, Boston limped into fourth place in 1876 and revenue dropped 17 percent. Only cutting expenses kept the team afloat.33

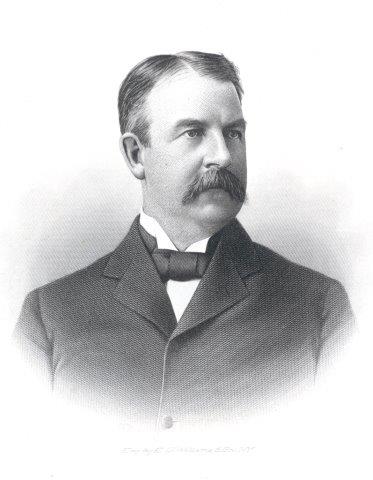

Arthur Soden, 1877-1906

The 1877 season “proved one of the most significant seasons in franchise and league history because of the influential new owners who purchased the Red Stockings.”34 The major player in the new ownership was Arthur H. Soden, who would run the franchise for the next 30 years.

A year or two before, Soden had purchased three shares of stock for $45 and he continued to build his stock holdings.35 The Boston “Booster” Club was dissolved after the 1876 season, and its shares were absorbed by the Association. A total of 78 shares were now divided among the Association’s membership.36 A December 6, 1876, meeting ended in dispute over a quorum being present, then a later meeting saw disagreements, perhaps between those who owned stock in the Club versus those of the Association. “The affairs of the association are mixed up considerably, some claiming that a part of the stock is dead, and others that is not,” the Transcript reported. The ownership “has got into a serious family quarrel over the respective rights of the club and association stockholders,” the Springfield Republican reported. “Some members left the meeting in disgust.” The meeting was adjourned until December 27, when “upon this decision being made the books and property of the old club were turned over to the Association,” wrote the Globe. Once the dust settled, Porter had resigned and Soden was elected club president, a post in which he would remain for three decades.37

Soden, a Civil War veteran, had formed Chapman and Soden Company, a roofing and supply business in downtown Boston.38 In baseball ownership, he was joined by two other executives, James B. Billings, a shoe factory owner, and William Conant, a manufacturer of hoop skirts and rubber goods. They became known as the “Triumvirs,” in reference to the Ancient Roman triumvirate of Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus. “Boston’s threesome wielded fully as much power in the National League as their predecessors wielded in the Roman league, and they survived to live considerably longer and happier lives,” wrote Boston sportwriter Harold Kaese.39 These Triumvirs were known for their New England frugality: Complimentary tickets were unheard of during their reign, and the budget for hotels and road trips was slashed. The Triumvirs themselves would be seen selling and collecting tickets at the gate.40

The Red Stockings (known as Red Caps or just Reds at this point, although fans still called them Red Stockings) won back-to-back pennants in 1877-1878. There was a large financial dropoff happening, however, after 1877, which saw nearly $31,000 in revenue. For 1878 it fell to $25,000 and for 1879 to just under $20,000.41 Historian David Quentin Voigt noted Boston’s net losses from 1876 to 1880:42

- 1876: ($777.22)

- 1877: ($2,230.85)

- 1878: ($1,433.31)

- 1879: ($3,346.90)

- 1880: ($3,315.90)

“Although managerial austerity, salary cuts, and new stock issues lightened the burden somewhat,” Voight wrote, “it was a discouraging picture.”43

On the field the 1879 season saw a big change, with George Wright and Jim O’Rourke leaving Boston for the Providence Grays, Wright becoming manager. The two teams’ rivalry became more intense. With the additional departures of Jack Manning, Andy Leonard, and Harry Schafer, only manager Harry Wright remained in Boston from the National Association days. Harry’s Boston team finished second in 1879 to George’s pennant-winning Providence squad. The club fell to sixth-place finishes in 1880 and 1881; receipts for 1881 totaled $21,647.42 with a balance-on-hand of $75.08. A new grandstand ($1,400) was mentioned among the expenses.44

Soden was among other club officials who met in Buffalo on September 29, 1879, with NL President William Hulbert. The results of the meeting ushered in a new era in baseball history, as teams now had the right to designate five players in a Reserve Clause that prevented them from signing with another team. This kept struggling teams from losing star players to the highest-bidding teams, and while the clause originally was limited to five players, over time it was expanded to the entire roster. (The clause went unchecked for nearly a century until the Messersmith/McNally decision in 1975.) While Soden has often been pictured as the mastermind of the Reserve Clause, his role was probably more in collaboration with other executives.45

Boston improved to third in 1882 (45-39) and revenue increased by $13,000, to $62,224.43.46 The manager that year was John Morrill, who succeeded Harry Wright after 11 years. Sportswriters also began referring to the Boston team as the Beaneaters, and the name would last through the 1890s.

In 1883, the pitching of Jim Whitney (37-21, 2.24) and Charlie Buffinton (25-14, 3.03) and the hitting of Jack Burdock (.330) and John Morrill (.319) powered Boston to a surprise pennant. At the annual meeting, 63 shares of stock were represented and amendments were made to the bylaws including one that “empower[ed] the board of directors to dispose of stock on certain conditions, and direct[ed] that hereinafter the treasurer shall submit his report to the directors instead of to the stockholders.”47 Clearly, the Triumvirs were consolidating their control. Due to illness, no expense report was given.48 Soden raised season-ticket prices from $20 to $30, which led to a petition by 33 stockholders and season-ticket purchasers.49 He also withheld dividends.50

Boston fell to second in 1884, fighting not only Providence but also another Boston team, which played in the new Union Association and was managed by George Wright. The annual meeting in December had 67 shares represented and for the first time the Triumvirs were mentioned as the first three officers, with Soden president, Billings treasurer (as A.J. Chase retired), and Conant general manager. The stockholders voted to purchase the South End Grounds, which the club had leased since 1871, for $100,000, financed mostly by a mortgage.51

The 1885 club finished fifth. At the annual meeting in December, stockholder George Lloyd demanded that a committee be appointed to investigate a number of issues: first, stock being sold to “sundry individuals” and returned for nonpayment; second, the fact that the membership had not received a treasurer’s report for 1883 or 1884; third, what were the reasons for the purchase of the South End Grounds and what were its terms and conditions; fourth, the changes in the bylaws; fifth, whether the directors have voted themselves salaries and how much; and sixth, a full financial audit. Lloyd was also disturbed because “a large majority of the shares of stock are held by three or four gentlemen.” (The Triumvirs owned 60 of the 78 shares of stock.) Lloyd’s motion failed to pass.52 By the 1886 meeting, however, tensions had eased.53 The team finished fifth again in 1886.

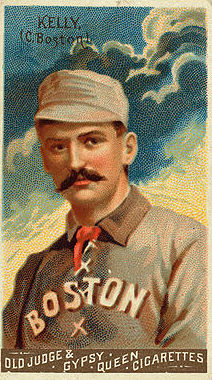

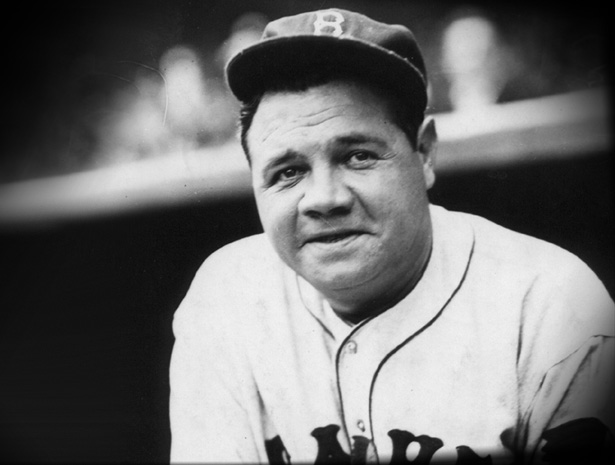

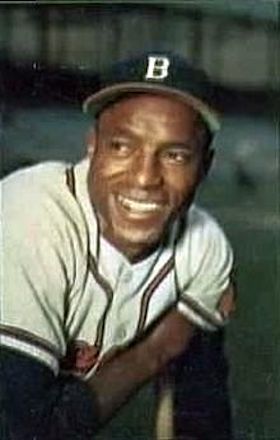

Despite a reputation for frugality, there were moments the Triumvirs flexed their wallets when a goal was in mind. On February 14, 1887, they made an announcement that the Herald said “will not only carry a thrill of joy to the heart of every admirer of the national game in Boston, but will create a sensation throughout the entire base ball world.” Boston paid Chicago $10,000 for “the best all-around player to be found on the diamond,” Michael “King” Kelly.54 The Babe Ruth of his day, Kelly had tremendous skill (his .388 batting average led the league), but his performance was dimmed by his rowdy character, and trouble often followed him. Kelly’s salary was $5,000. Still, Boston finished fifth.

Despite a reputation for frugality, there were moments the Triumvirs flexed their wallets when a goal was in mind. On February 14, 1887, they made an announcement that the Herald said “will not only carry a thrill of joy to the heart of every admirer of the national game in Boston, but will create a sensation throughout the entire base ball world.” Boston paid Chicago $10,000 for “the best all-around player to be found on the diamond,” Michael “King” Kelly.54 The Babe Ruth of his day, Kelly had tremendous skill (his .388 batting average led the league), but his performance was dimmed by his rowdy character, and trouble often followed him. Kelly’s salary was $5,000. Still, Boston finished fifth.

Late in the 1887 season, the Triumvirs announced plans to replace the “old, time-worn, rickety structure which has served as a grand stand on the Boston league base ball grounds for many years,” reported the Herald, “and a new, elegant and commodious one erected in its place in time for next season’s sport.”55 The park would be built on the same Walpole Street site. The cost was initially estimated at $35,000, but wound up close to $70,000. The Herald reported that the team had made $100,000 in 1886, so the new stadium was considered a high-cost risk. The Triumvirs decided to take the higher-cost project rather than settle for a less expensive structure.56 The “elaborate two-tiered, curving grandstand, complete with a series of towers featuring conical ‘witches caps,’ was compared to a medieval castle. Designed by Philadelphia architect John Jerome Deery, the new ballpark had a seating capacity of 6,800.

The annual meeting in December again brought minority stockholders into focus. They questioned the expenses of the organization and the lack of dividends. They questioned the Kelly purchase, considering that “the impossibility of winning the prize [pennant] next year will not make the public come in greater numbers.” Soden claimed he had not seen the financial books, but was sure they showed a profit.57

Soden still was spending money, acquiring star pitcher John Clarkson from Chicago for the now-familiar price of $10,000. “News that Boston had at last secured Clarkson got out upon the street last night,” reported the Herald, “and hearty congratulations were heard on every hand. Most complimentary allusions were made to Messrs. Soden, Conant, and Billings for the liberality they had displayed and the determination they had evinced, and successfully carried out, to meet the desires of the Boston base ball public.”58

The new ballpark opened on May 26, 1888, to great fanfare and a crowd of 15,000, well above the maximum. “There was scarcely foothold on the cars bound to the south end, drawn by jaded and wearied animals,” the Herald wrote. The season itself was a disappointment in the standings, as Boston finished fourth, but an estimated 300,000 came to visit the new palace.59 Newspapers didn’t report an annual meeting that year, possibly because Lloyd, the last minority stockholder, had sold out.60 At the end of the season the triumvirate were in a spending mood again, sending $30,000 to the Detroit Wolverines for Charlie Bennett, Dan Brouthers, Charlie Ganzel, Hardy Richardson, and a returning Deacon White. Brouthers led the league in hitting (.373) and had 118 RBIs. Clarkson went 49-19 and Old Hoss Radbourn won 20. Boston finished second, a mere game behind Chicago; the pennant was decided on the last game of the season. Still, attendance was 295,000 at the South End Grounds and a $100,000 profit was reported.61

In 1890 there was a mass exodus of players not only from Boston but other NL teams to join the new Players League. Boston finished fifth (76-57), a disappointment to new manager Frank Selee. Attendance was only 147,539, no doubt affected by the Players League rivals in Boston. Fearful of losing more talent, the Triumvirs signed players to multiyear deals, and while the rival league didn’t last beyond 1890, the club was stocked with talent for a three-year pennant dynasty. First baseman Tommy Tucker, shortstop Herman Long, and young pitcher Kid Nichols brought championships and revenue to Boston. The 1891 club finished 87-51 with Nichols and Clarkson winning more than 30 games each to compensate for the team’s weak hitting. Attendance rose to 184,472.

The 1892 club won 102 games (102-48) and captured a postseason series against Cleveland. Both Nichols and Jack Stivetts won 35 games, but attendance dropped to 146,421. The 1893 club finished 86-43 as Boston’s new faces, dubbed the Heavenly Twins, outfielders Tommy McCarthy and Hugh Duffy, batted .346 and .363 respectively. Nichols was again the ace, with 34 wins. The attendance rose to 193,300, who celebrated another pennant for Selee’s crew. “The record the Triumvirs liked best,” wrote Kaese, “was made at the gate. The club made money, as well as base hits, and the Triumvirs rejoiced, as well they might after several lean years during which they practically carried the whole National League on their dollar-padded shoulders. Time after time, Nick Young, president of the National League, called on Soden to rescue a sinking club during these years, and always Soden threw out a life preserver filled with ten thousand or more bills.”62

Boston was expected to repeat as champion again in 1894, but tragedy struck on the field and off. Catcher Charlie Bennett’s career ended in a horrible train accident in the offseason. Then the South End Grounds burned down on May 15. “The fire destroyed the bleachers, the $75,000 grandstand … and some 170 buildings covering twelve acres around the park,” wrote Kaese. “The total damage was estimated at one million dollars.”63 The fire, later dubbed the Great Roxbury Fire, burned 12 acres, destroyed 200 buildings, and left 1,900 homeless.64 A city-installed hydrant at the ballpark reportedly could have contained much of the fire, but the Triumvirs had not paid the $15 city water tax, so it was shut off.65 There is altogether too much of the ‘penny wise and pound foolish’ method in the management of their club business,” wrote Sporting Life.66 Many of Boston’s games were held at the nearby Congress Street Grounds while the third version of the South End Grounds was being built. The team returned on July 20 to a much smaller ballpark, since insurance did not cover the cost of a full rebuild.

After two mediocre seasons, Boston was again pennant-bound in 1897 with a 93-39 record and attendance that jumped from 240,000 to 334,800, upsetting the three-year reign of the Baltimore Orioles. Seven starters on the team batted over .300 and Kid Nichols won 31 games. The season was legendary for the emergence of the Royal Rooters fan club led by local saloon owner Michael “Nuf Ced” McGreevey. The Rooters traveled with the club on road trips, bringing horns and rattles.67 The Beaneaters lost the meaningless (in standings and profit) Temple Cup series to Baltimore, the last such series. The club reportedly made $120,000 profit.68

The team repeated as the pennant winner in 1898 with a 102-48 record, tied for most wins in franchise history until surpassed by the Atlanta Braves’ 104 wins in 1993. Despite the dominance on the field, attendance dropped to 229,275 and the club’s profits dropped to $90,000.69 “Was it the [Spanish-American] war,” wrote Kaese, “or were Boston fans growing a little tired of the success of the Beaneaters?”70 They had won five pennants in eight years, but this was the climax of the Triumvirs’ reign and the 1899 team fell to second. “Attendances were not good,” wrote Kaese, referring to the drop to 200,384 patrons in 1899. “The Triumvirs were more unpopular than ever. There was dissension among the players. … The great Beaneaters were no more. The minor flaws of 1899 became major fissures in 1900.”71 It was the worst Boston club since 1886, finishing 66-72. And it wasn’t going to get any easier as the twentieth century began.

Soden, who had fought off rival leagues in his three decades with the club, had little left to fight off the new American League. He looked like “a weary Roman emperor facing a new horde of barbarians,” wrote Kaese. Determined to make the AL a success, Connie Mack signed a lease for a plot of land on Huntington Avenue. Boston was going to have a new team in 1901. Star players Jimmy Collins and Hugh Duffy were among the defecting Beaneaters. At this point, the Triumvirs looked old and out-of-touch, being “too complacent, too confident,” wrote Kaese. “They understood the strength of Ban Johnson’s new league. They were going to brush that fly off their noses when they got around to it, but they were too slow getting around to it. The fly turned out to be a hornet, and the Triumvirs got stung. … The Triumvirs had become symbols of stinginess. In saloons and on street corners they were ridiculed by fans who took their cue from the newspaper writers.”72 While the Boston Americans stayed in their pennant fight to the end of the season, the Beaneaters finished 69-69 in fifth. Their attendance of 146,502 paled in comparison to their in-town rivals, who drew 289,448 in their inaugural season. Kid Nichols finished his 14th and final season in Boston, and Selee managed his last game in Boston after 12 seasons and five pennants.

The pattern continued: poor performance, poor attendance and a fan base switching to the American League rivals. By 1904, even the Triumvirs succumbed as Billings resigned, selling his stock to Soden and Conant. Fred Tenney was hired as the new manager and given stock, being told by Soden, “We don’t care where you finish, so long as you don’t lose money with the team.”73 One way Tenney saved the team money and earned favor with Soden and Conant was by racing into the stands to retrieve foul balls.74

By the time the 1906 season began, Soden and Conant were looking for a buyer for their team, which was devoid of talent, was surpassed in popularity by the Americans, and who played in a ballpark greatly in need of repair.75 The era of the Triumvirs was approaching an end.

George B. Dovey & John S. Dovey, 1907-1910

The Dovey Brothers, George B. and John S.C., paid $75,000 and assumed the $200,000 mortgage on the South End Grounds to buy the Beaneaters in October of 1906. Tenney closed the sale on behalf of Soden and Conant.76 He retained his 40 percent of stock.77 The Doveys had begun with large interests in the coal industry in Kentucky. But after flood damage, they switched to railroads. Behind the Doveys’ money was financial support from Barney Dreyfuss of the Pittsburgh team and John Harris, a Pittsburgh theater man. Their involvement remained unknown to the public. “We will do everything in our power to give the club the prestige it once had,” George Dovey said later, “and if we do not succeed it will not be from lack of effort.”78

One of the first decisions Dovey made was to change the team uniforms, eliminating the red stockings that had been prominent since the team was founded in 1871. This came on the advice of Tenney, “who fears that the dye in any colored stocking is apt to give blood poisoning when a player is cut … sliding or on being spiked on a play or a bruise from a shinnied ball or a pitched ball.”79 The home uniforms would be white and the road uniforms blue. These colors have essentially been the Braves’ colors ever since, while the red stockings look was taken by the other Boston major-league team, who became known as the Red Sox in 1908.

Another move was to have “the prettiest score card ever published in this city, to see that it will be a souvenir every visitor to the grounds will desire to carry away with him.”80 Upon touring the South End Grounds, Dovey discussed improvements with John Haggerty, the superintendent of the grounds. The visitors’ clubhouse, which had always been in the basement on the left-field side in the middle of the grandstand, would need installations of showers and heat, lockers, and a couch.81 Plans were also made for a new press box on the roof of the grandstand, extending the length of the middle section. “A box directly back of the catcher will be assigned to the telegraphers and on either side of this reservation will be four boxes, one for each paper,” wrote the Herald. “Each press box will seat five persons. A stairway will lead to the press boxes from the rear of the grand stand, and no one will have access to it except the scribes and their invited guests. This is a needed reform and will shut out intruders who have hitherto usurped privileges to which they were in no way entitled.”82 Dovey’s brother, John S.C. Dovey, resigned from his St. Louis car-company position to be the team’s business manager.83

The Boston baseball world was shocked at two tragedies in as many days during spring training in 1907. On March 28, Boston Americans manager Chick Stahl committed suicide at the age of 34. The very next day, Dovey lost one of his very own players: outfielder Cozy Dolan died of typhoid fever, also at the age of 34. “This has been a peculiar trip,” Dovey said. “Yesterday afternoon, you brought us news of Stahl’s death, and now we are leaving on account of one of our own men. I don’t know how to express myself on the loss of Dolan, which I feel as keenly as any man who has been shoulder to shoulder with him on the diamond. … The team suffers a distinct loss.”84

The team was also dubbed the Doves during this time, although Beaneaters was also still used in newspapers. Sometimes both names appeared in the same article. No matter the team name, they finished seventh at 58-90, but attendance did rise to 203,221, an increase of almost 42 percent. Tenney was replaced by Joe Kelley. Tenney unsuccessfully tried to sell his $10,000 worth of stock to George Dovey for $12,500, but Dovey refused. Tenney held onto his shares until he was bought out by William Russell in the summer of 1910.

The seating capacity of the South End Grounds was increased to 11,000 for 1908 with the addition of 4,000 bleacher seats. The bleachers would extend from right field to left field with an entrance at the end of Columbus Avenue and at Cunard Street. About 500 more seats were added to the third-base bleachers.85 There was also discussion of building an awning “to protect the fans from the hot cinders and the clinkers of the trains” over the third-base bleachers.86 Some adjustments had to be made once the season started. On Opening Day “a horde of boys came over the back fence into the outfield bleachers,” the Herald noticed.87 The team itself barely improved in 1908, finishing sixth at 63-91, but the added seats helped raise attendance to 253,750.

On June 19, 1909, while scouting players in Ohio, George Dovey died of a hemorrhage. John assumed the presidency of the club. With all the changes, one thing remained constant: the failure of the Doves on the field. The team finished a dreadful 45-108 with a .223 team batting average and a league-high 340 errors. At the annual meeting, John P. Harris emerged as a stockholder wanting to take a more active role with the team. One plan Harris introduced was a portable stage so that vaudeville performances could be held at the South End Grounds in the summer.88 Harris, a future Pennsylvania state senator, “is credited with introducing the world to the motion picture theater,” according to his biography on the Pennsylvania State Senate website. Harris and his father “produced vaudeville shows and introduced Pittsburgh to its first motion picture presentation in 1897. The brief 30-second to five-minute reels showed while customers of an amusement center were entering or exiting from a live Vaudeville act.” The father-son team realized people might enjoy and, more importantly, pay to see an entire show on film. In 1905 the younger Harris created a “Nickelodeon” theater, and saw huge crowds pack it.89 The biography briefly mentions his financial involvement in the Pittsburgh National League team, but not about Boston, which was a very brief period compared to his success in the motion-picture industry.

William Hepburn Russell, 1911

“A squirrel on a treadmill couldn’t have produced more action with less progress than the Boston Nationals of 1911,” wrote Harold Kaese.90 On November 12, 1910, John S.C. Dovey sold his interest in the team to Harris, who stated, “I have confidence in its future, notwithstanding [its] lowly position, and believe that the team can be restored to its former strength.”91 Harris then sold his stock to William Hepburn Russell, Louis C. Page, George A. Page, and Frederic J. Murphy. Russell, a New York lawyer, was born in Hannibal, Missouri, and was a boyhood friend of Mark Twain. The Page brothers were in the publishing business in Boston, while Murphy was a Boston insurance executive. They paid $100,000 for the 765 shares of stock owned by Harris. Russell became club president.92 The new owners also purchased other shares bringing their total to 980 of the 1,000 shares available.93

Fred Tenney was brought back to manage for the 1911 season. The team was now known as the Rustlers. There was dissension among the Page brothers and Russell over trades Russell was making and over who had a say in team affairs. Meanwhile, Ned Hanlon, of 1890s Baltimore Orioles fame, was putting together an offer to buy the club outright from Russell, who was offering it for $250,000. Hanlon wished to move the club to Baltimore.94

On July 24, Russell bought out L.C. Page’s stock and “became to all practical purposes the chief owner of the Boston National Club,” wrote the Herald. Russell gave Page a certified check for $28,650, and that settled the squabbles. “I plan to sell between 200 and 300 shares of my entire holdings,” Russell remarked, “but this will leave me more than 600 shares myself. And now that I have Mr. Page’s stock, I shall make a statement I never have made before, and this is that the control of the Boston club is not for sale.”95 The team in 1911 was in last place at 44-107, the franchise’s worst mark until 1935. The team ERA was the worst in all of baseball at 5.08, far higher than the league average of 3.39. The attendance plummeted again, to 116,000.

Tragedy struck the Boston front office yet again. Russell died of a heart attack on November 21, 1911, the second club president in two years to die unexpectedly. The team had to be put up for sale yet again, this time by Russell’s estate.

James E. Gaffney, 1912-1915

James E. Gaffney was a millionaire New York lawyer and politician with strong Tammany Hall connections. He had a background in construction, having built Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal in New York City. He named John Montgomery Ward team president.96 Ward, a one-time baseball star and then a New York lawyer, desired to run a ballclub. Gaffney, with his political and financial connections, was recommended to Ward by New York friend John Carroll. The price the trio paid was around $180,000 for the team97 and assumption of a $210,000 mortgage on the ballpark.98 Gaffney had immediate plans to upgrade the South End Grounds, and depended greatly on the baseball advice of Ward.

James E. Gaffney was a millionaire New York lawyer and politician with strong Tammany Hall connections. He had a background in construction, having built Penn Station and Grand Central Terminal in New York City. He named John Montgomery Ward team president.96 Ward, a one-time baseball star and then a New York lawyer, desired to run a ballclub. Gaffney, with his political and financial connections, was recommended to Ward by New York friend John Carroll. The price the trio paid was around $180,000 for the team97 and assumption of a $210,000 mortgage on the ballpark.98 Gaffney had immediate plans to upgrade the South End Grounds, and depended greatly on the baseball advice of Ward.

“All were of the impression,” wrote John J. Hallahan of the Herald as Gaffney, Ward, and company explored the grounds in January of 1912, “that the changing of the home plate towards the third base bleachers and placing home plate and second base on a line where the right field fence joins the centre field bleachers would do away with having two short fields.” The grandstand would now have two new sections and the third-base bleachers were built higher and deeper. The left-field bleachers were taken out altogether. A high screen was built above the fence in right field “so it will not be an easy matter to knock the ball over.” Left field was to be increased from 250 feet to 350 feet, although other records indicate that the true distance became 275 feet. The other new item was the players’ uniforms. Once again they would wear red stockings and “it is very likely that a profile of an Indian’s head, denoting a brave, will be placed on the pocket of the shirt,” wrote Hallahan.99 Ward “is satisfied that the title ‘Braves’ will cling to his team next season,” wrote player turned sportswriter Tim Murnane in the Globe.100 The Braves nickname and the logo of an Indian head with full headdress were taken directly from Tammany Hall.101 So the team became the Braves, and as they say, the rest is history.

A new name and logo didn’t matter, as on the field the Braves of 1912 lost another 100 games (52-101), while the Red Sox won the World Series. Ward resigned as team president on July 31, selling all his holdings to Gaffney, and Gaffney became president.102 Johnny Kling’s one-year managerial career was a disaster, and George Stallings became the manager. The 1912 attendance was barely higher than the year before at a league-worst 121,000. “I’ve been stuck with terrible teams in my time,” Stallings said upon accepting the offer to manage, “but this one beats ’em all.”103

Things started to turn around in 1913, as the Braves moved “all the way” to fifth, finishing 69-82, and attendance grew by nearly 100,000, to 208,000. Gaffney bought more property to build a new grandstand, purchasing adjoining land and demolishing the properties there.104 But the work was suspended as Gaffney contemplated other ideas.105 He leased a tract of land in Somerville, outside Boston, that seemed suitable for a ballpark.106 The lack of seating capacity at South End was a major factor.

Things would not be the same in 1914, as the team dubbed the Miracle Braves won the World Series after being in last place 15 games behind on July 4. The club rallied by finishing 18-10 in July, 19-6 in August, and 26-5 in September, then swept the heavily favored Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. The Braves saw record attendance of 382,913, bettering every other NL team. Stallings would be known thereafter as “The Miracle Man” and his crew of memorable stars became legends in Boston. There was Joe Connolly and his .306 batting average in the outfield, the double-play combination of Johnny Evers at second and Rabbit Maranville at shortstop, with two 26-game winners on the mound, Dick Rudolph and Bill James. Still, Kaese called the Braves “weak, lucky, and game.”107 But Gaffney and Stallings are forever remembered for their roles in putting together the “miracle” team, an accomplishment when one considers that in the previous 10 seasons the club finished eighth five times, seventh three times, and fifth and sixth once each.

When the Braves returned from a road trip on Labor Day to play a doubleheader against the New York Giants, the games were moved to Fenway Park. Close to 75,000 turned out to see the two teams battle for first place. Joe Lannin, a one-time stockholder in the Braves and now the Red Sox owner, gave Gaffney free use of Fenway Park for the remainder of the Braves’ home games. August 11 was the last official major-league game at the South End Grounds.

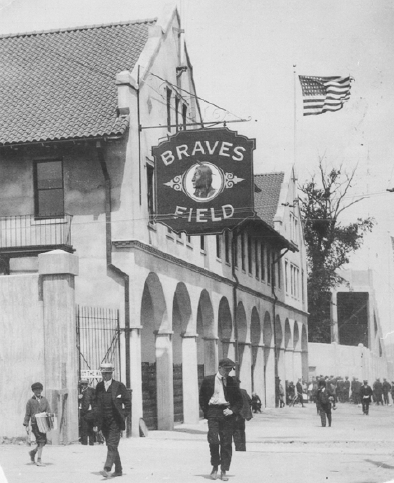

A crowd heads toward Braves Field. The ticket and administration building (shown at left) still stands and today serves as the headquarters for the Boston University police. Note the trolley tracks in the foreground, indicating the path of transit vehicles exiting from within the ballpark itself. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

When the 1915 season began, the Braves continued to play home games at Fenway Park. Gaffney had purchased a plot of land on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue that would become Braves Field for $600,000.108 It was the site of the former Allston Golf Club, bordered by the railroad once again with “belching smoke and cinders.”109 Ground was broken in March 1915 and the team could use Fenway Park until the new ballpark, dubbed Braves Field, was completed. It was a dramatic change of venue when the new ballpark opened on August 28.

“Players who moved from the chummy South End Grounds to new Braves Field complained of loneliness. It was like moving from a modern three-room apartment into a nineteenth-century mansion,” wrote Kaese, referring to the new 40,000-seat facility, the largest such at the time.110 Kaese noted that the cagey Gaffney had built the ballpark on the back of the lot so he “was able to sell the frontage at a handsome profit and also do the cleaners and launderers a good turn by putting his customers within easy range of smoke from the railroad yards when the wind was easterly.”111 The Braves fell to second place in 1915, Gaffney’s last as team president. In his short time he had been a part of a miracle championship and built a ballpark that would be used as long as the franchise was in Boston.112 But Gaffney sold the team in January of 1915. Gaffney, Kaese noted, “was essentially a businessman, not a sportsman. He admitted selling the Braves for a lot more than the $187,000 he had paid for the team four years earlier.”113 The deal didn’t include Braves Field, on which Gaffney continued to collect rent.

Percy D. Haughton, 1916-1918

Gaffney sold the Braves on January 8, 1916, to a syndicate including the bankers Millett, Roe, and Hagen, who had financed the construction of Braves Field. Percy D. Haughton, the hard-nosed football coach at Harvard, was elected team president, while former Massachusetts Governor David I. Walsh was named vice president. Arthur C. Wise became the treasurer. Wise was an investment banker who later became treasurer and director of the Boston Garden Corporation.114 The reported $400,000 price for the Braves did not include Braves Field, which Gaffney retained. Gaffney had not even publicly announced that the Braves were for sale. “But when I discovered that I could secure a price upon the stock that would net me a substantial profit I could not, as a business man, turn down the proposition,” he said.115

Haughton was said to be “as happy as Henry Ford with a new idea,” in the words of N.J. Flatley in the Herald. Haughton said, “I want to make it clear to the tens of thousands of baseball fans in this city and vicinity that in devoting my time to the club and its interests in the future I shall strive to give the patrons of the game exactly as high and, if possible, even a higher standard of baseball at Braves Field than they have been accustomed to witness in the past.”116

Haughton gave a good impression of a college football coach’s speech when he addressed the team at spring training 1916. “We are not going to sit down and wait for the fans to come to us. We are going right out and get them. Today I sold 13 season box tickets myself. When I went into this baseball business I was informed that it was soft. I was d—fool enough to think it was. But it isn’t. … [I]t’s hard work all the time. But hard work is what I like and what I live for. We intend to keep the Braves fighting. We don’t like rowdyism, but we’re strong for clean, hard, aggressive winning ball.”117 The new boss also unveiled an insurance plan for the players, with a “preventative” health system in which “the best of doctors will always be at the beck and call of our ballplayers, and we will have a healthy team anyhow, whether we win or not.”118

Haughton took out a $500,000 insurance policy to cover the Braves so that in the event of “the wiping out of the whole ball club in an earthquake, tidal wave or any other huge calamity, the entire $500,000 would have to be paid over, and there may be times this summer when P.D. Haughton will be tempted to shoot the 30 men and spend the money.”119

Some changes were made to Braves Field prior to Opening Day. “A swell lunch room has been installed in the back of the grand stand,” beamed R.E. McMillon of the Journal, “and the first tier of boxes has been lowered to permit an (uninterrupted) view for those who sit in the second tier. … Concrete had to be split apart by hand drills and the entire grandstand front lowered by excavation. As it now stands there isn’t a bad seat in the grandstand.”120 Hot-air balloons were launched on Opening Day and an energetic crowd of 8,000 filed it.121 The 1916 team, despite a lower attendance (313,495, down 62,788), was near first place throughout the season.

The 1917 and 1918 clubs were nothing in comparison, finishing under .500 both years (72-81, 53-71), and attendance nosedived (174,253 and 84,938) as World War I outshadowed baseball. The 1918 regular season ended on September 2 as baseball was not considered essential employment in wartime. Haughton resigned as president in July after the US Army Department of Chemical Warfare with the rank of major.122 Haughton would not return to the Braves, and the team would be sold early in 1919.

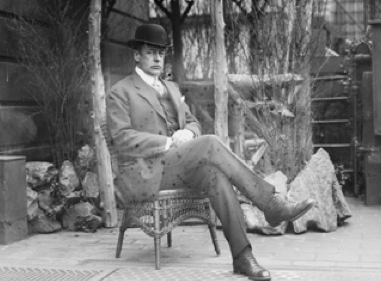

George Washington Grant, 1919-1922

George Washington Grant, whom Harold Kaese described as a “somewhat mysterious … derby-wearing … cane-carrying”123 friend of John McGraw, purchased the Braves on January 30, 1919, from Miller, Roe & Hagen. Grant had spent the previous 10 years “being the pioneer American moving picture house man in England,” owning cinemas and selling them for a huge profit in 1917.124 He returned to the United States “where he has since been casting about for an opportunity in some enterprise that looked attractive,” wrote the Globe.125 He had sold newspapers growing up in Cincinnati and developed a love for baseball. He became a messenger boy and delivered copy to the desk of Ban Johnson, the sporting editor of the Cincinnati Commercial and later American League president.

The price for the club was reported as $400,000, which Grant paid in cash, and the deal included only the team, since Gaffney still owned Braves Field. His goal, according to the Globe, was to “endeavor to build up a championship team and improve the value of his investment … and not as a speculation.” Grant also had plans to make Braves Field a multipurpose stadium, saying, “I do not like the idea of the large amount of money invested in that plant working only about 70 days in the year.”126

Grant assumed the position of president, with Arthur Wise remaining as a director. “There is no better baseball city than Boston,” Grant said, “and that is one reason why the Braves appeal to me as a business proposition at this time. The fans here are loyal. But what they want, and what is the corner stone of success in the game, is a winning team. I want to succeed with the Braves, and to do so I must have a winner, although I realize one cannot be secured in a minute.” Grant had wanted to buy the Braves years before, when Russell owned the team, but Gaffney and Ward beat him to it. “My interests on the other side kept me away for a good many years,” he said, “but I always followed the big league games by the scores in the American papers.”127

Three weeks into his term, Grant announced that all grandstand seats, except box seats, would be available to any fan for 75 cents (plus the war tax) except on holidays. To that point, 3,000 to 4,000 grandstand seats would usually be reserved at an “advanced price” of $1.50. The first row of box seats would remain priced at $1.50, but the second and third rows were lowered from $1.50 to $1.00. “I cannot see the sense of having many of these seats vacant and compelling the patrons of the game to watch the game from further back,” Grant said. “I believe in giving the baseball public all I can give it for its money.”128

It was hard to get around Boston in 1919. Strikes among the streetcar workers raised fares, so Boston’s attendance was last in the league, although the total of 167,401 was an improvement over 1918. But the Braves finished sixth (57-82), so that may have had something to do with it, too. Grant, looking for quality outfielders, acquired the legendary athlete Jim Thorpe, who had excelled as an Olympian and star football player. Thorpe played in 60 games and batted .327, his best season of the six in his baseball career, but it would also be his last.129 Grant was also willing to trade away proven veterans, like pitcher Art Nehf and second baseman Buck Herzog. The return was, most importantly, cash (the Nehf deal itself was reportedly $55,000 along with four players). “All I ask,” Grant said, “is for the Boston baseball public to defer judgment until these things work out. I am the one who is paying the bills of the Boston club.”130 A report in the Herald estimated that Grant lost $40,000 on the team that season, while the pennant-winning White Sox made $400,000.131

One less loss kept the Braves (62-90) from falling into last place in 1920, but attendance (162,483) was on the bottom again. Stallings, the “miracle” manager, had seen enough, and resigned in November. Stallings’ eight-year stint ranks behind only Frank Selee and Bobby Cox for longest tenure of Braves managers. “The club was a contender for a couple of years thereafter [the World Series in 1914],” quipped O’Leary in the Globe, “and then chiefly because the owners could not see their way clear to strengthen the team by the purchase of new talent, it began to deteriorate and lose class despite all Stallings or any other manager that happened to be in charge of it could do.” Stallings was making $15,000, which according to the Globe’s O’Leary, “was more than a second division club could afford to pay.”132

The man Stallings once referred to as “my right eye,” Fred Mitchell, who helped Stallings with his pitching staff in the 1914 season, became the new Braves manager.133Mitchell was a fan favorite, and the team improved in attendance (318,627) and the standings (fourth place at 79-74). Grant estimated however, that the Braves easily lost $100,000 because of poor weather early in the season, prompting cancellations of three Saturday games.134 Still, 1921 was profitable for Grant.

Grant traded the popular Rabbit Maranville to Pittsburgh for $15,000 and three players, including Billy Southworth, who batted .308, and Walter Barbare, who hit .302. “I deeply appreciate the indulgence of Boston fans and their patience while we have been trying to rebuild the team. I realized that the fans would rally to the team as soon as we began to win,” Grant said.135

“I would give $50,000 for a pitcher or an infielder of known ability that was certain to fill the bill,” Grant said in early 1922. “But where am I to get such a player? The Boston Club could not afford to give any such sum for a minor leaguer and take a chance of his making good; that would be something of a gamble.”136

Despite success in 1921, neither Grant nor Mitchell would see such again. The 1922 season was a disaster when the Braves fell to 53-100. Rising star pitcher Hugh McQuillan was sold to the Giants so the Braves could mainly get $100,000 cash to make up for the losses of the team last in the league and at the gate (167,195). “My club must be reconstructed,” Grant said. “It takes money to pay running expenses and to buy ball players, and it hasn’t been coming in at Braves Field. The amount of money received in this deal will enable me to purchase promising young players, and I have done what I consider is for the best interests of the Boston club.”137

But Grant’s interest in the Braves had already soured. He was looking for a buyer, and the team was sold in January of 1923. Grant was always remembered as a cordial, friendly man who loved baseball. “Grant leaves the game with the best wishes and the high esteem of those with whom he came in contact here,” wrote Whitman of the Herald. “He was a game loser, yet a determined fighter for the best there was for his team and his manager. He goes to private life and expects to take a long vacation from business worries, along with Mrs. Grant.”138

“I am leaving my interests in Boston with much regret,” Grant said, “as I always have been received cordially here and will leave behind many friends. I have always been a fan 100 percent and I don’t believe that I will ever change.”139

Judge Emil Fuchs, 1923-1935

“Without any preliminary blare of trumpets, without signs, tokens or portents, the announcement of the sale of the club came like a bolt out of the blue sky,” wrote James C. O’Leary in the Globe.140 The new era began with a dinner party at the Lambs Club in New York City, according to Harold Kaese.141 John McGraw, New York Giants manager, had invited actor and songwriter George M. Cohan, noted commissary operator Harry M. Stevens, and Judge Emil Fuchs, a prominent attorney in New York City who had also been a city magistrate and deputy attorney general. Fuchs had defended such prominent clients as major leaguer Benny Kauff and Gov. Charles S. Whitman. McGraw excitedly pointed out to them the current owner of the Braves.

“Without any preliminary blare of trumpets, without signs, tokens or portents, the announcement of the sale of the club came like a bolt out of the blue sky,” wrote James C. O’Leary in the Globe.140 The new era began with a dinner party at the Lambs Club in New York City, according to Harold Kaese.141 John McGraw, New York Giants manager, had invited actor and songwriter George M. Cohan, noted commissary operator Harry M. Stevens, and Judge Emil Fuchs, a prominent attorney in New York City who had also been a city magistrate and deputy attorney general. Fuchs had defended such prominent clients as major leaguer Benny Kauff and Gov. Charles S. Whitman. McGraw excitedly pointed out to them the current owner of the Braves.

“Why, there’s George Washington Grant. Did you know you can buy his ball club for half a million dollars?” None of the three guests knew the Braves were for sale, and gave expressions of interest and curiosity. McGraw directly asked Cohan, who said he wasn’t interested.

The purchase of the Braves took place on February 20, 1923, although it was the legendary pitcher Christy Mathewson who garnered the headlines. George Washington Grant, after four years of ownership, sold the Braves to Mathewson, Judge Fuchs, and James Macdonough, vice president of Columbia Bank. Twenty-five percent of the club’s stock “has been and is still owned by Bostonians,” the Herald reported. “It is the idea of the new owners to interest Boston capital.”142 Both manager Fred Mitchell and business manager Eddie Riley were retained. Mathewson became the club president and treasurer and Fuchs the vice president. The price was listed as more than $500,000.

“The matter has been under consideration less than three weeks,” O’Leary wrote of the hush-hush deal, “and the interested parties kept it so closely to themselves that there was no inkling of the sale known outside until late yesterday afternoon.”143 O’Leary also reported that this new ownership group was the only one he had ever disclosed a price for, and “were the only ones that had ever seriously asked him to do so.”144

While Mathewson had the baseball know-how and the popular name, it was Fuchs & Co. who took on the financial burden. “I told (Mathewson) not to assume any financial burden,” Fuchs said years later in his memoirs. “The opportunity would always be there at the original price if the club were successful. I was always glad I did not permit him to assume that additional worry.”145

Mathewson had been gassed in World War I and had suffered from tuberculosis for the previous few years. He had been recuperating in the fresh air of Saranac Lake in upstate New York, and his physician warned that he might live only a couple of years if he attempted to return to baseball. But Mathewson accepted Fuchs’ offer, declaring, “I would rather spend another two or three years in the only occupation and vocation I know than to linger many years up in Saranac Lake.”146

“We will try to give Boston the best,” Fuchs said. “We have enough money. You must have patience. It is a fact in baseball history that the best loved teams have been those developed in the city where they have won championships. The process of building up such a team requires time.”147

Fuchs and Mathewson were the stars of Boston in the first month after the purchase as they stirred up interest in the Braves. “They are taking the city by storm,” wrote Burt Whitman in the Herald. “They chat affably and intelligently with the chamber of commerce, the City Club, the Engineers, the newsboys or the Press Club. They have a message of better baseball at Braves Field, believe in that message, and talk manfully and cleanly of what they plan and hope to do.”148 These good vibes also extended to the players when it was announced that every Braves player would receive a raise for the 1923 season, as Fuchs announced Mathewson’s desire “to have satisfied and contented players on the team.”149

Fuchs admired Mathewson not just for his baseball wisdom but also his temperament. Known as “The Christian Gentleman,” Mathewson served as a moral model Fuchs wanted the Braves to be known for, whether they were a winning club or not. “He wants his team to win,” wrote O’Leary, “but he wants it to win without resorting to tactics that will injure players, that take an unfair advantage of opponents, or that offend the high ideals of patrons. … The new Braves will stand for only that which is clean and aboveboard. Fuchs wants the Braves to be a family.”150

Fuchs and Mathewson not only had dreams of improving the team on the field, but also using the field in other capacities to generate needed income. On May 1 the Herald displayed a picture of Fuchs and Mathewson signing contracts with Marcus Loew, motion-picture entrepreneur and vaudeville magnate. The caption read that Loew was to “stage night motion pictures, band concerts, fireworks and vaudeville at Braves Field this summer.”151 Anticipation built over the highly publicized “Loew’s Opening Night,” on June 25, and a crowd of 8,000 came to enjoy the dancing, the stars of stage and screen, the movie Trifling with Honor shown on two large screens facing the grandstand with projectors mounted on the dugouts, and the fireworks. Two immense dance floors had been constructed between the grandstand and the baselines running from home plate, and Alex Hyde led a 40-piece orchestra on a stand erected under the netting behind the plate. Soft orange lights dominated the field with ever-changing colors from the spotlights. Deemed a success, “the huge stunt is booked for all clear evenings throughout the summer,” wrote the Herald.152 Loew created the Braves Field Exhibition Company as a corporation,153 but the costs were too high to continue.154

Another idea was ladies’ day, started in July. Women could enter the ballpark free of charge.155 This would become a regular feature at both Braves Field and Fenway Park.

The Braves finished the 1923 season 54-100, “good” enough for seventh place, four games better than the last-place Philadelphia Phillies. Fred Mitchell resigned as manager on November 12, but would remain with the Braves as a scout and business manager until retirement in 1938.156 The new manager would come from the New York Giants. In a major trade that Whitman of the Herald called “the biggest in which the Braves have figured in years,” the club acquired shortstop Dave Bancroft, who would become the team’s player-manager. Boston acquired in the deal outfielders Casey Stengel and Bill Cunningham, while sending to New York outfielder Billy Southworth, pitcher Joe Oeschger, and cash. Bancroft, wrote Whitman, “will be shortstop, captain and manager of a team that needs a lot of upbuilding.”157 At age 31, Bancroft was the National League’s youngest manager.

There was an unproved but widely believed rumor that the Braves were simply a farm club of the New York Giants and were under their influence. This idea harkened back even to the days of Gaffney and the Tammany Hall crowd. This trade did nothing to silence those whispers. The facts that Fuchs and MacDonough were from New York and were friendly with Charles Stoneham, the Giants owner; and that Mathewson was a disciple of McGraw, brought scrutiny to every transaction made. Whitman even wrote a piece to stop the “sputtering at New York control.” The biggest shareholder of the Braves, he wrote, was Albert H. Powell, a millionaire coal dealer in New Haven, Connecticut, who was “the owner of the biggest office building in Connecticut.” Powell had been buying up the remaining available stock in the club.158

Apparently this was enough to convince Whitman that there was no conniving, despite the fact that New Haven is closer to New York City than Boston. Nevertheless, this fact made it “fit and proper for the baseball muck-rackers to forget their jeering innuendo directed against the New York ownership of the Braves or the ‘pipe-line’ which leads … direct into the New York Giants office.” Powell also owned the Worcester Panthers club in the Eastern League, and his stock in Braves was listed at $250,000.159

Despite the optimism and the offseason trades, the Braves were in the cellar in 1924. They also finished last in league attendance, at just 177,478. One way to increase attendance and revenue would be playing on Sundays, which the Massachusetts legislature was discussing. The Herald reported that Fuchs said he was solicited by a lobbyist for $100,000 to add to a slush fund for bribing the legislators. “I will say that I was much astonished when the proposition was made,” the Herald quoted Fuchs as saying, “but the interview was a very short one, for I told the man … that the owners of the Braves would not pay a red cent for legislation of any character.”160 The next day Fuchs said he was misquoted and he denied getting the bribe offer.161

There were two historically significant games at Braves Field in the early part of 1925. Opening Day on April 14 included the first radio broadcast from Braves Field. WBZ had a microphone set up, and an announcer (whose name was not mentioned) called the action. The Springfield Republican said it was believed to be the first time a game other than a World Series contest had been broadcast.162 On May 9, the Braves hosted the Chicago Cubs in the first Jubilee Game, celebrating 50 years of the National League. Among the honored guests were old-time Braves player George Wright and former Triumvir William Conant.163

On May 20, the report came that the Braves were officially purchasing the Worcester club, making Powell and Fuchs the co-owners. “Their intent,” wrote the Herald, “will be to give Worcester a winning team in the Eastern League, put in a high-class manager, and incidentally develop a lot of young talent.”164 The very next day came the report of the new “high-class manager,” who was beginning a legendary managerial career. Casey Stengel, a veteran outfielder, saw his playing career end that very month. One of the World Series heroes for the New York Giants in 1923, Stengel was now a 34-year-old reserve outfielder on the Braves batting a meager .077. He was released by the Braves, and was then hired to be the team president and player-manager of the Panthers. “The team will be run without doubt in close co-operation with the Braves,” wrote the Herald, but neither Powell nor Fuchs would be an officer of the club itself. The move was approved by the Eastern League in June.165

“This was not wholly altruism on Fuchs’ part, not just a gesture of kindness toward an aging warrior,” wrote Stengel’s biographer, Robert W. Creamer. “In those days a minor-league team would be a good investment. Casey could still hit well enough to shine in the minors, and he was a headline name, certain to draw crowds in Worcester.”166 Stengel’s flamboyance entertained the crowds for the 1925 season, and the team finished a satisfying third.

Fuchs was in Pittsburgh to see Game One of the World Series on October 7. Later that night he was interrupted during his bridge game and told that Mathewson had died. The flag was lowered to half-staff for Game Two, and both the Senators and Pirates wore black armbands.167 The Braves board of directors on October 21 named Fuchs as club president. Powell was elected vice president and would continue as treasurer.168

On November 20, Fuchs and Powell moved the Panthers from Worcester to Providence, Rhode Island.169 Stengel requested and was denied a raise for 1926. Stengel instead became manager of the Toledo club. To make this happen, Stengel the manager released Stengel the player, and then Stengel the president fired Stengel the manager. Stengel the president then resigned.170 Albert M. Lyon, a Boston-area lawyer, became a member of the Braves board of directors in January 1926.171

On August 31, 1926, Fuchs bought out the 33⅓ percent stock holdings of Powell, who would remain in office until the end of the year. “This transaction makes Judge Fuchs one of the big powers in the National League,” proclaimed the Herald. Powell had recently acquired a coal mine in Pennsylvania to add to his real estate and wholesale and retail business ventures, and was devoting his time to these. “The Boston Braves franchise is now considered to be worth a million dollars,” the Herald reported.172 Powell remained in control of the Providence Grays, who were no longer associated with the Braves.173

The Powell shares didn’t stay in Fuchs’ hands very long. On May 15, 1927, they were purchased by Charles F. Adams, V.C. Bruce Wetmore, and Charles F. Farnsworth, with Adams being the major shareholder. Adams was well known in the Boston area as president of the Boston Bruins hockey club. He would now become vice president of the Braves, and was praised by Fuchs as “a true sportsman, a successful business man and a lover of baseball.”174 Wetmore, president of an electrical supply company, and Farnsworth were business associates of Adams.

“It is with great personal gratification,” said Fuchs, “that I am able to announce my success in inducing Mr. Charles F. Adams of Boston and Framingham, a true sportsman, a successful business executive and a lover of baseball, to purchase the holdings of Mr. Albert H. Powell from me, and join me in continuing our effort to give Boston an improved baseball club worthy of its approval and support.”175

Before the season ended, the Braves reacquired the Providence minor-league club, reportedly for $18,000.176

Manager Dave Bancroft was released at the 1927 season.177 Despite the optimism when he arrived in 1924, Bancroft’s tenure as manager saw the Braves finish eighth, fifth, and seventh (twice), with a record 249-363. Jack Slattery was named the new manager in early November.178 Slattery was a Boston-area native who had been coaching baseball at Boston College. Despite Fuchs’ word that Slattery was “a man of unquestioned character and loyalty, who we are absolutely satisfied, will give his all to his city and his club,”179 the outcome was a disaster.

Another move by Fuchs in the offseason was moving in the fences of Braves Field to provide more home runs for Braves’ hitters. The proposal was approved at the December meeting of the National League owners. “It seems that practically every other team in the league, as far as its players and managers were concerned, disliked to come to Braves Field and play on a field where the outfielders needed motorcycles to retrieve drives between the outfielders,” Fuchs said.180 The Braves had finished last and next to last in home runs the past two seasons. “I feel that the shortening of Braves Field will have the sure tendency to make the Braves of 1928 a more confident, fighting, aggressive ballclub,” said Slattery. “It surely was a liability to the Braves to play on that rifle range.”181 While dimensions varied in the accounts of the time, the left field fence was moved in from 402 to 320 feet, left-center from 402 to 330, center field from 550 to 387, and right field from 365 to 310.182

On January 10, 1928, the Braves made front-page headlines with a trade Whitman of the Herald called “the most important in which a Boston club has participated in many years.”183 The Braves acquired future Hall of Famer and .400 hitter Rogers Hornsby. His salary was $40,000 and included being “field captain” of the Braves, so the owners would need to “dig down deeply as a result of the trade,” Whitman wrote.

In spring training, Fuchs gave Hornsby a new contract “as a reward for the remarkable spirit he has demonstrated in coming to the preseason training in advance of the date on which he was ordered to report, and the industrious manner in which he had gone about the tedious work of preparing himself physically for the campaign.” The three-year contract was for $40,600 a year, with $600 being the expenses in being the “field captain.” It was the second highest salary in the major leagues, trailing only that of Babe Ruth.184

The new-look Braves Field brought a startling realization to fans immediately. After an 8-3 Opening Day loss to the Giants, Whitman remarked, “there was quick evidence that the new outfield bleachers will mean a tremendous number of homers at Braves Field.” Already, it was the opposing team hitting the majority of them. “It hurts to switch around your yard to help your rivals and so handicap yourself.”185 Fuchs made a quick solution in a matter of days. “We will put up a 10- or 15-foot wire netting,” he said. “If that is not enough to preserve the decent standards of the game, we’ll move back the stands, but not this year.”186 The Herald even joked that the new slogan of Braves Field should be “Buy a 75-cent left field bleacher seat and get a baseball free.”187 Finally in June, a 30-foot canvas was erected above the left-field fence. “We have received a large number of protests,” Fuchs said, “and all that I can say is that I agree with them all and will endeavor to remedy the situation as speedily as possible.”188

That trend of opposing team home runs continued all season, however, and the Braves home runs allowed rose from 43 in 1927 to 100 in 1928, while the Braves themselves hit 52, up from 37 in 1927.

With the Braves in seventh place in May, Slattery suddenly resigned, and Hornsby was “persuaded” to become manager.189 The Hornsby experiment ended on November 7 when he was traded to the Chicago Cubs for five pitchers and $200,000 of needed cash. Fuchs announced that he himself would manage the team in 1929, with Johnny Evers as his assistant and “right eye.” “These are the ingredients of the most sensational and most unusual baseball story which has broken in Boston in many and many a year,” Whitman wrote in the Herald.190 Now with money to spend, Fuchs seemed to be comfortable acquiring veteran players around him, and in addition to Evers, brought shortstop Rabbit Maranville and catcher Hank Gowdy, all three members of the Braves 1914 championship team. “If I don’t make good,” Fuchs reportedly said, “no one will realize it quicker than I, and it will be perfectly simple for me to remove myself as manager.”191