April 22, 1886: Visiting Athletics walk off Metropolitans in inaugural game at St. George Grounds

On April 22, 1886, construction wrapped up on New York’s home for America’s quintessential icon. The final granite capstone was “laid in silver mortar,” on the Bedloe’s Island pedestal for the Statue of Liberty, Auguste Bartholdi’s homage to American independence.1

On April 22, 1886, construction wrapped up on New York’s home for America’s quintessential icon. The final granite capstone was “laid in silver mortar,” on the Bedloe’s Island pedestal for the Statue of Liberty, Auguste Bartholdi’s homage to American independence.1

That same day, on nearby Staten Island, the brainchild of another foreign-born visionary opened its doors to the masses. Canadian-born Erastus Wiman’s St. George Grounds was hosting its inaugural baseball game. Hard by the St. George ferry terminal, the Grounds were the centerpiece of Wiman’s efforts to remake Staten Island into an entertainment destination.

In July 1884 his Staten Island Rapid Transit Company had purchased the ferry franchise linking the north shore of Staten Island with lower Manhattan and Brooklyn.2 Soon after, Wiman bought 10 adjoining acres east of the ferry terminal, a large field known as Camp Washington that had been leased to the Staten Island Cricket Club.3 There he planned to build an elegant casino, lawn-tennis courts, quoiting courts, and “fields laid out for cricket and baseball.”4

Wiman purchased the American Association’s Metropolitans baseball franchise from John B. Day (who also owned the New York Giants of the rival National League) in December 1885,5 intending to relocate the club from Manhattan to St. George.6 Association club owners feared Day’s sale was a ruse to weaken their circuit,7 so they revoked the Metropolitans franchise and announced plans to disperse players to the Brooklyn and Washington clubs.8

Wiman secured a temporary injunction,9 threatened to form a new rival league if not reinstated,10 then persuaded a Common Pleas judge in Philadelphia to vacate the expulsion.11 After that triumph, he successfully staved off an effort by Brooklyn Grays owner Charles Byrne to abscond with outfielder James Roseman and star first baseman Dave Orr.12

By mid-March of 1886, a “small army of masons and carpenters” had erected a single over-300-foot-long, 72-foot-high “Queen Anne style” grandstand on the former cricket grounds, with two decks accommodating over 4,000 spectators and a glass-walled ladies refreshment room.13 In keeping with the ballpark’s aesthetic of splendid views from every seat, the grandstand was oriented perpendicular to the path between pitcher and batter, rather than parallel to a foul line.

The Association champions in 1884, the Metropolitans fell on hard times in 1885, finishing 33 games behind the St. Louis Browns. Before the start of the 1885 season, Day transferred Metropolitans manager Jim Mutrie to the team that soon would be known as the Giants, and absconded with Mets ace Tim Keefe and third baseman Dude Esterbrook through sleight-of-hand.14 The hollowed-out Mets finished the season 44-64, in seventh place and demoralized.

During their 1886 preseason, the Mets twice downed the NL Washington Nationals on the road,15 then survived a riot during an exhibition game in Newark, New Jersey.16 They opened their regular season on the road in Philadelphia and Baltimore, splitting both series. With returning manager Jim Gifford at the helm, they carried a 2-2 record into their home opener against the Athletics of Philadelphia.

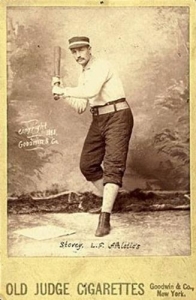

The Athletics, also 2-2, were led by manager Lew Simmons. Co-owner of the club, he appointed himself skipper prior to the 1885 season before being deposed by his partner, Bill Sharsig, and replaced by first baseman Harry Stovey. Despite limited managerial experience,17 Stovey guided the Athletics to a third-place finish.18 Simmons reclaimed the manager’s mantel for the 1886 season, and it remained to be seen how the team would react to his resurrection.

The grandstand was filled for the Thursday afternoon contest, with the temperature 81 degrees, the warmest day of the spring so far. Spectators who ferried to the game from Manhattan’s Whitehall terminal on the Southfield II or another of Wiman’s fleet19 enjoyed a cooling breeze as they steamed across the harbor. Once on the island, visitors were steps away from what the New York Times called “one of the finest baseball parks in the country.”20

Gifford chose southpaw Ed Cushman for the pitcher’s box opposite Athletics ace Bobby Mathews. Obtained by the Metropolitans from the Athletics midway through the 1885 season, Cushman had a sterling 2.78 ERA and 2.19 Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP) the rest of the way, but little to show for it, his Mets record only 8-14. In contrast, Mathews went 30-17, was second in the Association in strikeouts (286) and led all Association pitchers in strikeout/walk ratio (5.02), strikeouts per nine-innings, (6.1) and FIP (2.17). Both Cushman and Mathews had already pitched and won a game during the teams’ two-game series in Philadelphia.21

The Metropolitans lineup featured stout Dave Orr, the reigning American Association slugging leader and runner-up for the 1885 batting crown,22 with Roseman in center field, slick-fielding Frank Hankinson at third base,23 and 37-year-old Candy Nelson, the oldest player in the Association, at shortstop.

The Philadelphia lineup included leadoff hitter and reigning Association home-run king Harry Stovey, Henry Larkin, 1885 league leader in doubles (37), and third in batting average (.329), Orator Shafer, the major-league record holder for outfield assists in a single season (50), and shortstop George Bradley, a converted pitcher who fashioned the NL’s first no-hitter and a league-leading 1.23 ERA in 1876. Twenty-year-old rookie second baseman Lou Bierbauer (“Bauer” in most box scores) was to play his fourth major-league game.24

The Athletics took the “neatly sodded field first, as the New Yorkers elected to bat first, but came up scoreless.25 The Mets wore their eye-catching new uniforms, debuted days earlier in Philadelphia; white shirts adorned with a distinctive blue and white polka dot necktie, atop white pants with matching blue belt and stockings.26

Philadelphia pushed across two runs in the bottom of the inning, on an error by Cushman, a single by catcher Jocko Milligan, and a double by third baseman Jack O’Brien.27 The Mets halved the Athletics’ lead in the third on a hit by Tom Forster and Milligan’s passed ball. “[Finding] Mathews curves with small effort,” the Mets scored three more in the fourth on hits by Roseman, Hankinson, Forster, and Charlie Reipschlager, assisted by a walk, a passed ball, and an error by Bierbauer.28

The Athletics tied the score at 4-4 with a pair of runs in the fifth, the details left unreported. During the rally, Roseman injured a finger and was replaced by rookie Elmer Foster.29 Foster, nominally a replacement pitcher,30 was making his major-league debut.31 Gifford’s men took back the lead with a pair of runs in the top of the sixth, on a single by Steve Brady, a double by Hankinson, and Forster’s two-run double. Stovey brought Philadelphia within one in the eighth, as he singled to lead off, advanced to third on a pair of putouts and scored on a wild pitch.32

The Metropolitans led 6-5 heading into the ninth inning. By then spectators would’ve had time to stroll the grandstand promenade, which ran the length of the grandstand and out to the shoreline, providing unobstructed views of the harbor, the three cities it served – New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City – and Lady Liberty’s future home.33

New York was unable to add any insurance runs in its turn at bat. Milligan led off the bottom of the ninth with a “daisy cutter” fumbled by Nelson at short. O’Brien walked, putting the winning run on first. Bierbauer’s towering fly out to Steve Behel in left field energized the crowd, now “standing on their chairs and shouting for all they were worth.”34 After Reipschlager snagged a foul tip off the bat of Bradley, the Mets were one out from victory.

The crowd “breathed a sigh of relief” as Mathews, the Athletics’ weakest hitter, came to bat.35 He carried a lowly .201 career batting average heading into the season but had a hit earlier in the game and two more, including a double, in his Opening Day win over the Mets. Making Mets fans “feel very unpleasant,” he smacked a single to drive in Milligan, tying the score.

Up stepped the last batter the Metropolitans wanted to see – Harry Stovey. His rare combination of power, bat control, and speed enabled him to extend rallies with his bat or with his legs.36 Amid the crowd’s deafening roar, Stovey hit a grounder at second baseman Forster that he couldn’t handle. While Forster futilely chased the ball, O’Brien raced home with the winning run.37

Reviews for opening day at the Grounds were mixed. The New York Times reported clear views from the grandstand’s first row to its last.38 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle shared Polo Grounds personnel comments that the St. George grandstand was incomplete and the field was “not up to the mark.”39 The New York Tribune ominously noted that the crowd had considerable trouble in reaching the island and just as much getting back, but did call the grandstand “the handsomest of its kind in the country.”40

The Mets notched their first victory at St. George Grounds on May 6, snapping a 10-game losing streak with a one-hitter over the Athletics. Unimpressed, the New York Times called the game “interesting.”41 That same day, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle described how three “monumental asses” had adorned Lady Liberty’s new home with baptismal graffiti, carving their names into her pedestal.42 Welcome to New York!

Author’s Note

The author attended high school a few blocks away from the former site of the St. George Grounds. He’s also spent many hours admiring the Statue of Liberty (and her pedestal), while ferrying between St. George and Whitehall terminals.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact checked by Kevin Larkin and copyedited by Len Levin.

Sources

The author utilized his bio of St. George Grounds; Bill Lamb’s SABR bios for Erastus Wiman and John Day; Staten Island native Peter Mancuso’s SABR bio of Jim Mutrie; and Paul Hofmann’s SABR bio of Harry Stovey. He also obtained pertinent material from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Disassembled for transport from France, the statue was reassembled and attached to ironwork embedded within the concrete pedestal over the course of the next six months. Bedloe’s Island was donated to the federal government in 1801 by the City of New York for military use, and was renamed Liberty Island by Act of Congress in 1956.

2 “News in Brief,” Brooklyn Union, July 18, 1884: 2.

3Wiman purchased Camp Washington from the estate of financier George Law, exercising an option he’d negotiated several years earlier. After two previous options had expired, Law was said to have granted Wiman’s request for a third option after the latter offered to “canonize” Law by naming his planned ferry terminal St. George. . Soon after, the surrounding community adopted the terminal’s name as their own. “Staten Island Improvements,” New York Times, October 31, 1884: 8;; Legends, Stories and Folklore of Old Staten Island: The North Shore (New York: Staten Island Historical Society, 1925), 6

4 Quoiting was a game similar to horseshoe throwing, first brought to England by the ancient Romans. “Staten Island Improvements”, “Quoits – History and Useful Information,” https://www.tradgames.org.uk/games/Quoits.htm, accessed February 10, 2022.

5 “Base Ball by Electric Lights,” New York Sun, December 6, 1885: 2.

6 “Mr. Wiman’s Baseball Club,” New York Times, December 5, 1885: 8.

7 At that time, Staten Island had no direct access to neighboring Manhattan and Brooklyn, and was reachable only by boat “Erastus Wiman’s Trophy,” May 20, 2013, https://baseballhistorydaily.com/2013/05/20/erastus-wimans-trophy/, accessed February 7, 2022.

8 “A $25,000 Ball Club Dropped,” Buffalo Evening News, December 9, 1885: 1.

9 “A Lively Fight Promised,” New York Times, December 10, 1885: 2.

10 “A Rival New League,” Sporting Life, December 16, 1885: 1.

11 “Erastus Wiman’s Trophy.”

12 Showing he had no hard feelings, Wiman later commissioned a solid silver trophy, 26 inches high, to be awarded to the 1886 American Association champions at the end of the season. “The Baseball Muddle,” Marion County Herald (Palmyra, Missouri), January 1, 1886: 2; “Erastus Wiman’s Trophy.”

13 Future plans also called for the ability to play night baseball, illuminated by 12,000 electric lamps of 20 candle-power each, installed in trenches and arranged “so that every part of the field will be as light as day.” “Hard by the Ferry,” New York Times, March 14, 1886: 14; “Base Ball by Electric Lights.”

14 Day arranged for the Metropolitans to release Keefe and Esterbrook in March, then sent them, along with Mutrie, on a voyage to Day’s onion farm in Bermuda. This kept the players incommunicado during the 10-day period during which other clubs could sign them, under existing National Agreement rules. Before they returned, Mutrie signed Keefe and Easterbrook to Giants contracts.

15 “The Mets Beat the Washingtons,” Philadelphia Times, April 3, 1886: 2; “A Chilly Day for Baseball,” Philadelphia Times, April 4, 1886: 3.

16 Newark players and fans had taken exception to Mets “quiet and gentlemanly” second baseman Tom Forster persuading the umpire to call a balk on the Newark pitcher in the fourth inning. An argument between Forster and Newark captain Burns ensued and the pair clinched. The crowd poured on the field to join the fray, players defending themselves with their bats. One fan raised his revolver but was quickly seized by police, who’d been called in to quell the disturbance. “Almost a Riot on the Field,” New York Times, April 9, 1886: 8; “Riot on a Ball Field,” Philadelphia Times, April 9, 1886: 2.

17 Stovey had previously managed the National League Worcester Ruby Legs to an 8-18 record during the 1881 season.

18 Stovey, the first major leaguer to hit 10 home runs in a season when he did it in 1883, finished the 1885 season with 50 career home runs, the first major leaguer to reach that milestone.

19 The Southfield II was the newest of Wiman’s ferries at that time, having been commissioned in 1882. A pair of brand-new ferries would enter his ferry service in the next two years, including the eponymous paddle wheeler Erastus Winston. https://www.siferry.com/prevessels.html, accessed February 14, 1886.

20 “New St. George Grounds,” New York Times, April 23, 1886: 3.

21 Both pitchers were no doubt still adjusting to two new American Association rules that benefited pitchers – a one-foot increase in the depth of the pitching box and elimination of the inane rule requiring a pitcher to keep both feet on the ground when delivering a pitch. These two changes led to a record number of strikeouts during the 1886 season, including Matt Kilroy’s astounding 513, a major-league record that still stood after the 2021 season. Jimmy Keenan, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/october-3-1886-matt-kilroy-strikeout-king/.

22 A few years later, future Hall of Famer and five-time NL/AA batting champion Dan Brouthers called Orr “the strongest and best hitter that ever played ball.” Orr’s playing weight was 250 pounds and more. “Talks of Himself,” Sporting Life, September 22, 1894: 6.

23 Hankinson was credited in 1885 with the highest fielding percentage for an American Association third baseman (.906) and the highest range factor per 9 innings of any Association third baseman (3.56).

24 Bierbauer had replaced the previous Athletics second baseman Cub Stricker, who was let go because of poor performance thought to be caused by excessive drinking. “The American Clubs,” Sporting Life, November 4, 1885, 2.

25 “New St. George Grounds.”

26 “Spring Recreation,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 19, 1886: 3; Threads of Our Game, nineteenth-century baseball uniform database, https://www.threadsofourgame.com/1886-metropolitan-new-york/#, accessed February 14, 2022.

27 “The Opening Game on the Staten Island Grounds – The Metropolitans Defeated,” New York Sun, April 23, 1886: 3.

28 The seventh batter in the Mets lineup, who singled in this inning, was identified as “Foster” in the New York Sun box score and accompanying game summary, but was in fact Tom Forster, based on the author’s research as detailed in a note below. “The Opening Game on the Staten Island Grounds – The Metropolitans Defeated.”

29 Multiple box scores published the next day confused the first names, last names, and positions played by Mets Elmer Ellsworth Foster and Thomas “Tom” Forster. The New York Sun identified Roseman’s replacement as “E. Foster,” with “Forster” playing second base. The New York Tribune listed “E.E. Foster” as the replacement, with “Foster” at second. The Brooklyn Eagle identified “E. Foster” as the replacement with “T. Foster” playing second. The New York Times had “E. Forster” replacing Roseman, with “Foster” at second. The Philadelphia Times showed “C. Forster” replacing Roseman, with “Foster” at second, and the Philadelphia Inquirer simply listed “Forster” for Roseman and “Foster” at second. Historical defensive data for both players (excluding 1886, the only year that they were teammates, when this mistake could have been made all season long) shows Elmer Foster played 168 major-league games in the outfield (59 in center field) and 1 game in the infield (at third base), while Tom Forster played 10 major-league games in the outfield (4 in center field) versus 108 games in the infield (74 at second base). In addition, an early April 1886 New York Sun preseason profile of the Metropolitans players identified Elmer Foster only as a prospective pitcher and Tom Forster as the team’s second baseman. The author has therefore assumed that Elmer Foster replaced Roseman and Tom Forster played second base; consistent with the New York Sun box score.

“The Opening Game on the Staten Island Grounds – The Metropolitans Defeated”; “Metropolitans Beaten at Home,” New York Tribune, April 23, 1886: 8; “Sports and Pastimes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 23, 1886: 2; “New St. George Grounds”; “One for the Athletics,” Philadelphia Times, April 23, 1886: 3; “Metropolitan and Athletic,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 23, 1886: 3.

30 Foster, who’d broken his arm while throwing a pitch for the 1884 St. Paul Apostles in the Northwest League, never pitched in his five major-league seasons. “New St. George Grounds”; “The Pursuit of Elmer Foster,” September 9, 2015, https://baseballhistorydaily.com/2015/09/09/the-pursuit-of-elmer-foster/, accessed February 8, 2022.

31 Baseball-Reference.com and retrosheet.com identify April 17 as Elmer Foster’s debut; however, as detailed above, multiple newspapers reporting Metropolitan game results in early 1886 confused him with teammate Tom Forster. New York Times box scores from the four Mets games prior to the St. George Grounds opener all show “Foster” in the lineup at second base, which the author believes was in fact Tom Forster, the Mets’ regular second baseman for both 1885 and 1886, as listed by Baseball-Reference.com. “The Metropolitans Lose a Game to the Athletic Club,” New York Times, April 18, 1886: 7; “A Victory for the Mets,” New York Times, April 20, 1886: 5; “The Metropolitans Win,” New York Times, April 21, 1886: 5; “The Metropolitans Beaten,” New York Times, April 22, 1886: 2.

32 Errant tosses had been a bugaboo for Cushman, who uncorked 31 of them the previous season, fifth-most in the American Association.

33 “Hard by the Ferry.”

34 “The Opening Game on the Staten Island Grounds – The Metropolitans Defeated.”

35 “New St. George Grounds.”

36 The reigning AA home-run king, Stovey went on the lead the Association in stolen bases this season with 68, in the first year for which stolen bases were officially tracked.

37 The New York Sun erroneously reported that Mathews scored the winning run. “The Opening Game on the Staten Island Grounds – The Metropolitans Defeated.”

38 “New St. George Grounds.”

39 The Brooklyn Eagle also remarked that the opener at St. George Grounds drew prospective fans away from the Giants exhibition game at the Polo Grounds, there being “not a corporal’s guard witnessing the New York and Columbia game there, outside of the free admissions.” “Sports and Pastimes.”

40 “Metropolitans Beaten at Home.”

41 “The ‘Mets’ Win a Game,” New York Times, May 7, 1886: 3.

42 Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 6, 1886: 4.

Additional Stats

Athletics (Philadelphia) 7

Metropolitans (New York) 6

St. George Grounds

Staten Island, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.