August 19, 1891: King Kelly slides back into Boston for Reds win before jumping to Beaneaters

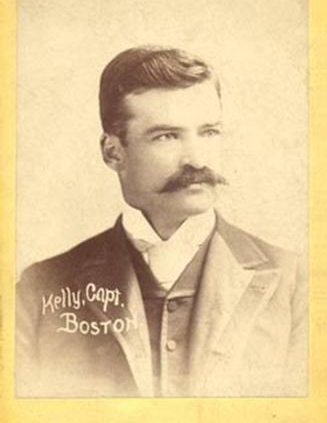

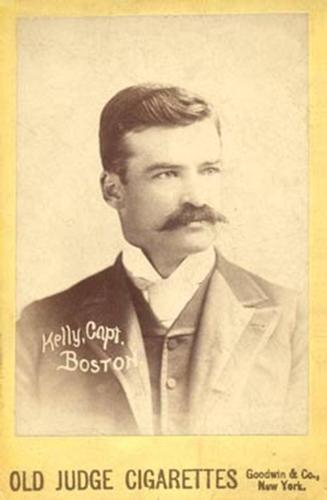

Boston’s love affair with Mike “King” Kelly fittingly began on Valentine’s Day. It was on February 14, 1887, that the Boston Base Ball Club of the National League agreed to pay $10,000 to Al Spalding and the Chicago White Stockings for the rights to the 29-year-old reigning NL batting champion. In its front-page story breaking the news, the prescient Boston Herald predicted, “The advent of Kelly in the Boston team will create an enthusiasm … such as would follow the acquisition of no other player in the profession.”1

Boston’s love affair with Mike “King” Kelly fittingly began on Valentine’s Day. It was on February 14, 1887, that the Boston Base Ball Club of the National League agreed to pay $10,000 to Al Spalding and the Chicago White Stockings for the rights to the 29-year-old reigning NL batting champion. In its front-page story breaking the news, the prescient Boston Herald predicted, “The advent of Kelly in the Boston team will create an enthusiasm … such as would follow the acquisition of no other player in the profession.”1

Before long, Beaneaters fans turned “Kelly the King” into the biggest celebrity athlete since Leonidas of Rhodes.2 Handed the captain’s role, the “$10,000 Beauty” drew legions of adoring fans to see him play at South End Grounds.3 On his way into the ballpark, Kelly was hounded by schoolchildren for autographs, which he invariably provided in pencil.4

Kelly was an ingenious defender and fearsome competitor, but it was his daring on the basepaths that truly made him a sensation. His novel hook slides befuddled opponents as they tried to tag him out, enabling him to steal bases with abandon. In his first year with Boston, Kelly swiped 84 bases, many preceded by encouraging cries of “Slide, Kelly, slide” from the stands. Two years later, a baseball-themed ditty of the same name became America’s first pop hit.

The Beaneaters’ fortunes improved in each of the three years Kelly played for them, but they fell short of winning a pennant. Whether a backstop, outfielder, infielder, or in the pitcher’s box, he remained the club’s top attraction.

When NL owners agreed to clamp down on players’ salaries for the 1890 season, and brazenly published Kelly’s salary history to help justify their actions,5 he joined many of his peers and jumped to John Montgomery Ward’s Players’ League. Kelly poked a stick in the eye of the Beaneaters’ majority owners, Arthur Soden, J.B. Billings and William Conant (collectively known as the Triumvirs), by choosing to play for their new crosstown rivals, the Boston Reds.

In June Spalding secretively offered Kelly $10,000 to jump back to the National League, but he declined.6 Two months later, adoring fans and admiring Players’ League competitors chipped in to buy Kelly a house and a riding coach with two white horses. As manager, part-time catcher, and general-purpose substitute, Kelly led the Reds to the pennant, but financial losses spelled the end of the Players’ League after one season.

Reds majority owner Charles A. Price negotiated a move to the American Association for the 1891 season but elected not to bring Kelly along.7 Unwilling to return to the National League, Kelly joined the Association’s new Cincinnati franchise, becoming their manager, captain, and – in the fashion of the day for marquee player-managers – their namesake. When he first came to bat for Kelly’s Killers in his first game back in Boston against the Reds, ever-loyal Hub fans gave Kelly another horse and carriage, a six-foot-tall floral horseshoe, and a round of “He’s a jolly good fellow.”8

Unable to draw fans to wretched Pendleton Park,9 Kelly’s Killers folded on August 13. After telling the press he didn’t have an offer to return to his first Boston employer, the Beaneaters, Kelly accepted an offer to return to his most recent one, the Reds.10 “‘The King’ is coming,” read the lead in the Boston Globe’s announcement, along with a transcript of Reds manager Frank Bancroft’s telegram declaring Kelly “true blue.”11 “I’ll try to make the Boston Association team the finest attraction in the land,” said Kelly as he headed east.12

The Globe’s 5 P.M. edition on Wednesday, August 19, gave station-by-station updates of Kelly’s progress on the last leg of his travels from St. Louis to Boston. “I’ll get there if I have to slide,” promised Kelly as he boarded a train in Albany, New York.13 He had to run to catch his next train, bound for Pittsfield, Massachusetts, dropping his bat, bag, and gripsack (for delivery by the next train) to “a chorus of ‘slide, Kelly, slide’” from onlookers. By 3 P.M., Kelly made it to the year-old Congress Street Grounds, and “marched on the ballfield clad in a Boston uniform once more.”14

Fifteen minutes later it was time to play ball, with upward of 10,000 admirers on hand to see Kelly and the Reds face the Baltimore Orioles in the finale of a three-game series.15 Kelly was behind the plate, with Charlie Buffinton, who’d won his 20th game of the season in the series opener, pitching.16 In addition to having his hands full snaring Buffinton’s knee-bending overhand drops, Kelly also bore the responsibility of being the team’s captain.17

Batting first, Boston quickly took the lead. Baltimore hurler Sadie McMahon, the reigning Association leader in wins, complete games, innings pitched, and strikeouts, was greeted by Reds leadoff hitter Tom Brown’s bloop double over the head of soon-to-be lame-duck shortstop Irv Ray.18 Brown moved to third on a fly ball by Kelly’s predecessor as Reds captain, Hugh Duffy, and scored on a single by Kelly’s displaced fellow royal, third baseman Duke Farrell, dubbed “the king of all catchers” before the season by the Boston Globe.19

Two batters later, as Kelly approached the plate, the Reds presented him with a stand of flowers and a card that read in part, “Long live the King.”20 The Orioles players paid tribute as well, each shaking Kelly’s hand in turn. Baltimore’s largesse didn’t extend to Kelly’s turn at bat as they retired him for the last out of the inning.

After denying the Orioles in the bottom of the first, the Reds scored again in the second. Singles by Hardy Richardson, his first of four in the game, and the light-hitting Buffinton started the rally.21 After a sacrifice by Cub Stricker failed, the speedster took matters into his own hands and stole second. A single from pious Paul Radford,22 playing for his seventh team in seven years, gave Reds a two-run lead. Stricker got caught in a rundown between third and home on a groundout by Brown before Duffy’s single knocked in Radford and Brown.23

Down 4-0, the Orioles responded in the second inning. Lefty Johnson doubled off the left-field fence and moved to third on a single by Pete Gilbert. Johnson scored on a double steal, with Gilbert advancing to third on Kelly’s errant throw. He died there as Buffinton fanned both Curt Welch, five years removed from his $15,000 slide, and McMahon.

In the fourth, the Reds added a pair of runs. Singles by Farrell and eventual batting champ Dan Brouthers, followed by a Kelly out, gave Boston their first run.24 A single by Richardson gave them their second.

Baltimore shaved a run off the lead in the fifth, though how was a matter of debate. George Van Haltren reached third on what the Baltimore Sun called a muff and fumble by Duffy, the right fielder, while the Boston Globe claimed Van Haltren hit a clean triple over the head of Brown, who appeared in their box score, along with Richardson, as one of Boston’s two left fielders. Regardless, Van Haltren scored after consecutive walks to Perry Werden, Sam Wise, and Johnson.

From that point on, neither side could push across another run. No Oriole even reached base after Welch drew the fourth Baltimore walk of the day in the sixth. Despite getting little on offense from Kelly, the Reds triumphed, 6-2.

Surely exhausted, Kelly kept himself out until the ninth inning the next day, in a home game with the Athletics of Philadelphia. The following day he collected two singles, stole a base, and bowled over Athletics catcher Jocko Milligan to score a run, and hit a two-run home run the day after that. Then, just as suddenly as Kelly had joined the Reds, he was gone.

Kelly jilted the Reds to return to the Triumvirs for the princely sum of $25,000, covering the balance of the 1891 season and 1892 as well, with a $10,000 option. The reaction of his Beaneaters teammates was aptly captured in a Boston Globe headline; “Boys Tickled, at Kelly’s Slide into the League’s Arms.” A bemused and/or betrayed “unknown bard” offered:

King Kelly came to Boston town,

And he was wondrous slick;

He jumped the leaguers in a trice,

Because “dey made him sick,”But when he got a horse and house,

With all his might and main

He put ten thousand in his vest

And jumped straight back again.25

When word of Kelly’s jump back to the Beaneaters reached members of an American Association executive committee about to start negotiating a truce with National League counterparts in Washington, DC, they stood up, left the room, and formally terminated discussions.26 Demands that Kelly be returned to the Reds were rebuffed by the NL.

In second place when Kelly came aboard, three weeks later the Beaneaters began an 18-game winning streak that gave them the National League pennant.27 The Reds held onto their spot atop the American Association without Kelly. When Association President Zack Phelps formally challenged the National League to a renewal of the annual postseason series between the two leagues, NL President Nick Young declined.

King Kelly remains the only ballplayer to play for two pennant-winning Boston nines in the same season.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.com for pertinent material. He also consulted Peter M. Gordon’s SABR biography of King Kelly, Bill Lamb’s SABR biography of Charlie Buffinton, David Nemec’s The Beer and Whisky League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994), and Marty Appel’s Slide, Kelly, Slide (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1999). Other sources included box scores and game summaries published in the Boston Globe during the 1887, 1890, and 1891 seasons.

Notes

1 “A Trump Card,” Boston Herald, February 15, 1887: 8.

2 Leonidas was a sprinter credited with winning an unmatched 12 individual Olympic victories in the ancient Olympic Games of 160, 156, and 152 BC. “Kelly, the King,” Boston Globe, February 15, 1887: 1.

3 The term “$10,000 Beauty” had first been applied in 1881 to actress Louise Montague after she won circus owner Adam Forepaugh’s $10,000 prize for “the handsomest woman in the country.” “Mike Kelly at Haverhill,” Boston Globe, April 7, 1887: 2; “Personal,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Intelligencer Journal, April 4, 1881: 2.

4 Marty Appel, Slide, Kelly, Slide (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1999), 114.

5 Slide, Kelly, Slide, 148.

6 After declining, Kelly somehow persuaded Spalding to lend him $500. Peter M. Gordon, King Kelly SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/king-kelly/.

7 Charlie Bevis, “Boston Brotherhood/Reds team ownership history,” SABR Team Ownership History Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/boston-brotherhood-reds-team-ownership-history/.

8 “A Horse, A Horse!” Boston Globe, May 7, 1891: 5.

9 Pendleton Park, built on the banks of the Ohio River, with a small, rickety grandstand, sat at the eastern limit of Cincinnati. The ballpark proved too remote, and too desultory, to draw many fans.

10 “Will Stick,” Cincinnati Post, August 15, 1891: 1; “The King Coming,” Boston Globe, August 17, 1891: 1.

11 “The King Coming.”

12 “With Best Wishes of All,” Boston Globe, August 18, 1891: 8.

13 Kelly was also willing to slide some money into the train engineer’s palm to get there. He offered the no-doubt surprised engineer “$50 to get him through on time.” “Kelly’s Catch,” Boston Globe, August 19, 1891: 1.

14 “Kelly’s Catch.”

15 Attendance was listed as 10,067 in the Boston Globe, 11,000 in the Baltimore Sun and Sporting Life. “Rousing Reception,” Boston Globe, August 20, 1891: 3; “Bostons Win Again,” Baltimore Sun, August 20, 1891: 6; “Kelly’s Popularity,” Sporting Life, August 22, 1891: 1.

16 Buffinton’s record based on game log compiled by the author.

17 The day before his arrival, Kelly was given that honor. Former captain Hugh Duffy, who the Boston Globe hinted had reluctantly taken the role, was “delighted to have Kelly take charge of the team.” “Duffy Was a Success,” Boston Globe, August 19, 1891: 5.

18 The next day, the Baltimore Sun reported that Orioles manager Billy Barnie had signed an 18-year-old ballplayer from Tuxedo, New York, who would, within a week, replace Ray as the Orioles’ regular shortstop: John McGraw. “A Short Stop Signed at Last,” Baltimore Sun, August 20, 1891: 6.

19 Farrell caught the eye of Sporting Life for his catching and throwing during his 1888 rookie season with the Chicago White Stockings, and for his batting and baserunning as well while with the Players’ League Chicago Pirates in 1890. Those high-profile kudos, along with sportswriter and former ballplayer Tim Murnane’s plaudits for his fast style of play, positive attitude, and commitment to fitness seemed to be the basis for the high praise Farrell was given coming into the 1891 season. Yet it wasn’t Farrell but rather Morgan Murphy who was displaced behind the plate with Kelly’s arrival. Farrell had been playing third since the Reds’ regular third baseman, Bill Joyce, broke an ankle in early July. Ironically, author Peter Morris in Catcher identifies Farrell, in his later years, as one of several catchers who diminished the prestige of the catching position, by being able to hold onto starting jobs despite falling badly out of shape. “Bostons Win Again”; “Prince Smiles,” Boston Globe, March 7, 1891: 1; Peter Morris, Catcher (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010), 245.

20 “Bostons Win Again.”

21 A career .245 hitter, Buffinton hit only .188 in 1891, with a measly .227 slugging percentage.

22 Radford, a devout Sabbatarian, refused to play on Sundays throughout his 12-year career.

23 Duffy had already been rewarded once before in that inning when the Reds presented him with “a handsome gold-headed cane” and a note of thanks for his services as captain. “Kelly’s Popularity.”

24 In their game summaries published the next day, the Boston Globe called Kelly’s out a sacrifice and the Baltimore Sun described it as a groundout.

25 “Boys Tickled.”

26 In his history of the American Association, The Beer and Whisky League, author David Nemec speculates that the timing of Kelly’s poaching by the Beaneaters was engineered to kill the peace conference. “Boys Tickled,” Boston Globe, August 26, 1891: 1; David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994), 228.

27 The streak also included one game, against the Pittsburgh Pirates on September 17, that ended in a tie, on account of darkness.

Additional Stats

Boston Reds 6

Baltimore Orioles 2

Congress Street Grounds

Boston, MA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.