August 24, 1918: Cubs clinch fifth National League pennant in 13 years with doubleheader sweep

On August 24, 1918, the Chicago Cubs hosted the fifth-place Brooklyn Robins, who were 24½ games back of first place but had won nine of 15 games against the front-running Cubs. The second-place New York Giants were 10½ games out of first with a little more than a week left in the season and the Cubs were on the verge of clinching their fifth pennant since 1906. The 1918 season was scheduled as usual and teams were expecting to play the same 154-game set they’d been playing since 1904, but that would be interrupted by the United States’ entry into World War I.

On August 24, 1918, the Chicago Cubs hosted the fifth-place Brooklyn Robins, who were 24½ games back of first place but had won nine of 15 games against the front-running Cubs. The second-place New York Giants were 10½ games out of first with a little more than a week left in the season and the Cubs were on the verge of clinching their fifth pennant since 1906. The 1918 season was scheduled as usual and teams were expecting to play the same 154-game set they’d been playing since 1904, but that would be interrupted by the United States’ entry into World War I.

On April 4, 1917, the US Senate voted in favor of President Woodrow Wilson’s request for a declaration of war against Germany. The House agreed two days later and the nation was effectively an entrant into World War I, triggered on June 28, 1914, with the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Two major factors finally helped Wilson convince Americans it was time to aid the Allies against the Central Powers. Germany reneged on an agreement to stop targeting US ships with their submarines, and its foreign minister sent a telegram asking Mexico to join it in the war in return for help regaining territory it lost to the United States in the Mexican-American War.1

Thanks to the Selective Service Act, which required men from 21 to 30 to register for military service, and 2 million volunteers, approximately 4.8 million soldiers were sent to Europe to fight the Central Powers. But General Enoch H. Crowder, the judge advocate general of the United States Army, wanted to ensure that every able-bodied man assisted in the war effort, so he issued a “work or fight” order on May 23, 1918, declaring that baseball was a “non-essential occupation,” and that baseball players had until July 1 to enlist in the military or get a job in a shipyard or defense plant. If they declined to do either, they would be inducted into the service.2

At the time of the announcement, the 1918 season was still young. The Giants had played 30 games, won 23 of them and held a four-game lead over the Cubs; the American League’s Boston Red Sox had played 31, won 19 and boasted a two-game edge over the New York Yankees and Cleveland Indians.

In July, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker officially enacted the work-or-fight order and baseball had a problem on its hands. Washington Senators catcher Eddie Ainsmith lost an appeal of his draft eligibility on July 19 and was expected to join the military. Two days later AL President Ban Johnson ordered the league to cease its operations.3 But two coalitions that included Red Sox owner Harry Frazee, Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith, and all eight National League magnates persuaded Crowder and Baker to allow the season to continue until September 1 with the World Series to be completed by September 15.4

By the end of July, the Cubs had taken over first place in the NL, holding a 3½-half-game lead over the Giants, who had the only chance of catching them. The next closest team, the Pittsburgh Pirates, was already 11½ games off the pace and the rest were at least 16½ games back.

By mid-August the Cubs had stretched their lead to six games over the Giants and they extended it to eight with a doubleheader sweep over the Phillies on August 17 and a Giants loss to the Cincinnati Reds. Time was running out on John McGraw’s men and the hole was even deeper at the end of play on August 23, when the Giants sat 10½ games off the pace with a little more than a week left in the season.

All the Cubs needed to do to clinch the pennant was take both games of a doubleheader against Brooklyn at Chicago’s Weeghman Park on August 24. The first step was easier than it should have been against pitcher Burleigh Grimes, who had won 10 consecutive decisions, including nine starts. But Chicago rolled to a convincing 8-3 win in the first tilt behind a 15-hit attack led by Charlie Picks’ three safeties, and a nifty outing by Claude Hendrix, who earned his 19th win against only six losses. The second affair pitted Cubs rookie hurler Speed Martin against veteran right-hander Larry Cheney.

Martin had made his season debut on August 3 and was making only his third start of the season and fifth of his young career. In his first six appearances, three as a reliever, the six-foot righty was brilliant, going 3-1 with a 0.68 ERA, and had just tossed a three-hit shutout against the Boston Braves five days earlier. He also helped secure a 3-2 win over the Giants with an inning of scoreless relief just a day before.

Cheney, on the other hand, was in his seventh full big-league season. Having debuted on September 9, 1911, the spitball artist threw 10 scoreless innings for the Cubs in a cup of coffee before taking the NL by storm in 1912 with a league-leading 26 wins. He won at least 20 games in his first three seasons, going 67-42 from 1912 to 1914, but his days of dominance were all but over by 1918, and he was 11-11 with a slightly-worse-than-league-average 2.83 ERA going into the August 24 contest.

Just as it had in game one, Brooklyn struck first, this time with a run in the top of the third. Catcher Otto Miller doubled, Cheney moved him to third with a sacrifice bunt, and Miller came home on a wild pitch. It could have been worse had Pick not made a “spectacular stab” of Jimmy Johnston’s line drive that saved Martin from another base hit.5 Johnston had also been robbed of a hit in the first game when center fielder Dode Paskert made a nice running grab on a shot destined for extra bases.

Losing a second hit in as many games was too much for Johnston and he lost his composure. “This peeved Jimmy so much,” wrote the Chicago Tribune’s I.E. Sanborn, “that he threw the ice water pail out of the Robins’ dugout and made them all go dry the rest of the day.”6 Unfortunately Brooklyn’s bats also went dry and they didn’t score the rest of the day, either. Meanwhile, the 32-year-old Cheney was channeling his younger self and had a shutout going until the bottom of the seventh, when the Cubs plated two to take the lead.

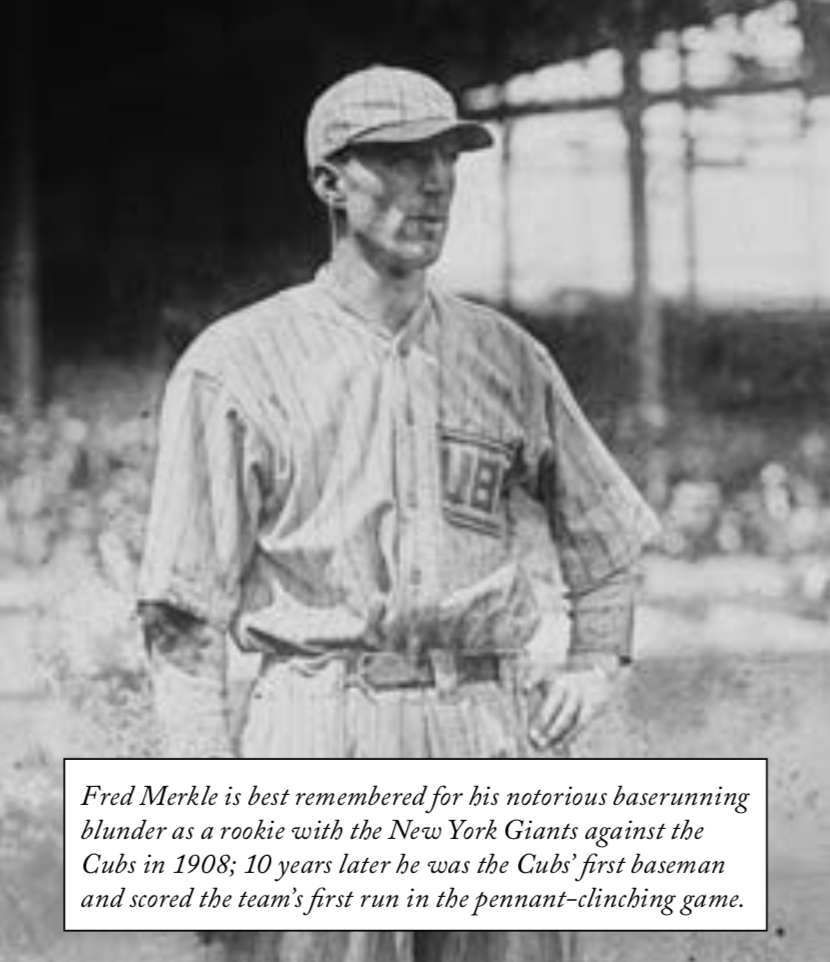

Fred Merkle, the former Giant who helped the Cubs win the 1908 NL pennant with a baserunning blunder that earned him the nickname “Bonehead,” followed a Paskert out with a free pass, then tied the score at 1-1 on a Pick two-bagger to left. Pick scampered to third on a wild pitch and, after Cheney retired Charlie Deal for the second out, Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson ordered an intentional walk to catcher Bill Killefer.

Killefer was a weak-hitting catcher with a .229 career average going into the 1918 season, who was hitting .220 on August 18 before he left the team for a fishing trip near his boyhood home in Paw, Michigan. But he was an outstanding defensive catcher, prompting Sanborn to quip, “If [Killefer] is as good at catching fish as baseballs there are some vacant ‘homes’ in the depths of Paw Lake.”7

The Cubs backstop was 1-for-2 with a strikeout against Cheney in his two previous at-bats and the even more anemic Martin was on deck, making Robinson’s decision easy. But Killefer spoiled the strategy when he offered at ball four and “pickled” it for a single over second, “driving in the run that would have been enough to win.”8

Chicago added a run in the bottom of the eighth for good measure and the 3-1 victory earned the Cubs their first pennant since 1910. “As nearly as can be doped out of the tangle produced by the curtailed schedule,” waxed Sanborn, “the Cubs drove the ultimate spike into the 1918 National league pennant yesterday. … The McGrawites cannot play enough games to catch up even if the Cubs lose the rest of their own battles.”9

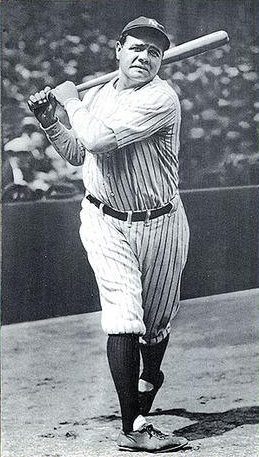

Indeed. The Cubs went 84-45 in the abbreviated season and finished 10½ games ahead of the Giants before losing the World Series in six games to the Boston Red Sox.

This article appears in “Wrigley Field: The Friendly Confines at Clark and Addison” (SABR, 2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more stories from this book online, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed below, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and The Sporting News.

Notes

1 US State Department’s “Office of the Historian” web page (history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/wwi); The 1914 Allies, Russia, France, and Great Britain, were joined by Italy in 1915, Romania in 1916, and the United States in 1917. The Central Powers were originally Germany and Austria-Hungary before they were joined by the Ottoman Empire in 1914 and Bulgaria in 1915.

2 Eugene C. Murdock, Ban Johnson: Czar of Baseball (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1982), 124; “Baseball May Stop if New Order Stands,” New York Times, May 24, 1918.

3 J.V. Fitz Gerald, “Baseball’s Fate Up to Majors’ Meetings,” Washington Post, July 21, 1918.

4 Michael Lynch, Harry Frazee, Ban Johnson and the Feud That Nearly Destroyed the American League, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 51. If the sporting world thought it was immune to the war it was served a heaping dose of reality in mid-July when Lieutenant John W. Overton, a former Yale track star who held the world record in the indoor mile at 4:16, was killed in action in France during the Second Battle of the Marne.

5 I.E. Sanborn, “It’s All Over! Flag for Cubs; Land 2 Games,” Chicago Tribune, August 25, 1918.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid. Recording a hit during an intentional walk was much more common in the Deadball Era than it is today, especially now that pitches aren’t even thrown per 2017 rules. But if you’re wondering how the fourth ball was close enough to hit, consider that Cheney led the National League in wild pitches six times in nine seasons and walked over 100 men in a season three times, including a league-leading 140 in 1914.

9 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Chicago Cubs 8

Brooklyn Robins 3

Chicago Cubs 3

Brooklyn Robins 1

Weeghman Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Game 1:

Game 2:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.