July 13, 1977: New York City blackout adjourns Mets-Cubs game for two months

A sparse crowd of 14,626 turned out on July 13, 1977, a sticky Wednesday night and the first day of what became a nine-day heat wave (average high 97.1 degrees).1 They were at Shea Stadium to root for the New York Mets, securely in last place in the National League East at 34-52, against the first-place Chicago Cubs (52-32), who enjoyed a four-game lead over the Philadelphia Phillies.

A sparse crowd of 14,626 turned out on July 13, 1977, a sticky Wednesday night and the first day of what became a nine-day heat wave (average high 97.1 degrees).1 They were at Shea Stadium to root for the New York Mets, securely in last place in the National League East at 34-52, against the first-place Chicago Cubs (52-32), who enjoyed a four-game lead over the Philadelphia Phillies.

The trade of “The Franchise,” Tom Seaver, four weeks earlier, at the insistent urging of combative2 New York Daily News columnist Dick Young, for an underwhelming four-player return,3 contributed, along with the Mets’ last-place status, to the small crowd that night. But what seemed like an ordinary weeknight game would take a memorable twist, after events in the sixth inning that no one on hand could foresee.

The pitching matchup was a good one. Ray Burris (9-8), with two 15-win seasons already under his belt at age 26, took the mound for the Cubs. Jerry Koosman (6-10), age 34 and one season removed from 21 wins and a Cy Young Award runner-up finish, opposed Burris for the Mets. With Seaver departed, Koosman was the ace of the Mets staff.

The first five innings were almost as mundane as the midsummer weeknight setting. Third baseman Steve Ontiveros gave the Cubs a 2-0 lead in the second when he followed center fielder Jerry Morales’s walk with a two-run homer to deep left. Right fielder Mike Vail got one of those runs back for the Mets in the bottom of the fifth on a home run to right field. Only Koosman’s performance, as he kept Chicago off balance with 10 strikeouts through five innings, suggested that it could be a memorable night.

The Cubs carried their 2-1 lead into the sixth inning. The top of the frame passed uneventfully, although Koosman got Jerry Morales as his 11th strikeout victim. He had already whiffed both Bobby Murcer and Ivan deJesus three times each. In a 2020 interview, Koosman remembered thinking the single-game major-league strikeout record of 19 — set by Seaver in 1970 — was within his reach because all his pitches were working that night.4

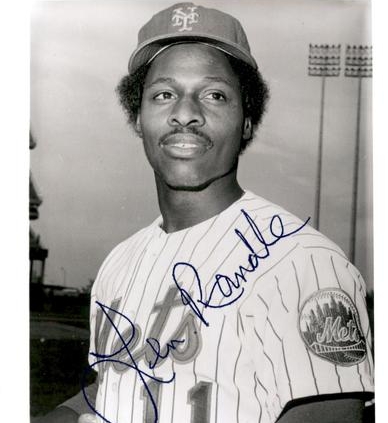

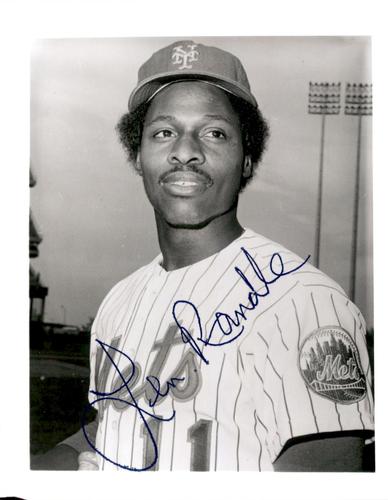

With one out in the bottom of the sixth, Mets third baseman and fan favorite Lenny Randle stepped into the box. It was 9:31 P.M.

Burris got ready to throw and the lights went out all over New York City. The blackout had begun.

Shea Stadium plunged instantly from electric illumination to all-encompassing darkness, throwing many participants and spectators into confusion and at least one player into fear. Randle believed he was dying. “God, I’m gone,” he thought. As he told the New York Times afterward, “He (God) was calling me. I thought it was my last at-bat.”5

Burris, still clutching the ball in the dark, saw Randle take a phantom swing and begin to run the bases. In a 2017 interview, Burris told Vice Sports he threw the ball at Randle as he rounded second base.6 Whether Burris threw the ball, which would be a dense missile aimed in the dark right at his middle fielders, cannot be verified. Broadcaster Howie Rose, covering the game for a local radio station, rejected any idea that a ball was flying around in the blackness. Randle recalled being tackled by deJesus and second baseman Manny Trillo as he came into second base, perhaps because he was “showing up” Burris by pretending to have walloped the ball.7

An emergency generator provided electricity for the corridors and ramps under the stands. Concession stands were immediately closed “to defuse the potentially dangerous parlay of heat, darkness and beer” on the orders of Mets vice president James K. Thompson.8

In the absence of a baseball game, organist Jane Jarvis entertained the crowd for an hour by playing familiar tunes like “White Christmas” so the crowd could sing along.9 Joel Youngblood drove his customized van through the center-field fence and turned on the headlights to illuminate the infield. Craig Swan followed with his Buick. Swan later said, half-jokingly, that the Mets owed him a full tank of gas for this contribution to the lighting.10

Phantom infield practice broke out, with pitcher Bob Apodaca as the batter, catcher Jerry Grote behind the plate, pitcher Jackson Todd at first, second baseman Doug Flynn at his natural position, Bud Harrelson at shortstop despite the cast on his broken right hand, and infielder Bobby Valentine at third.11 After Apodaca “hit” the ball the infielders would “relay” the ball around, adding in a flourish of slides that raised dust visible in the headlights.12 At one point, official scorer Red Foley called an “error” on Valentine.13

Koosman recalled attempting to stay loose, in hopes of continuing to chase the strikeout record if the electricity was restored. Mets players later went over to the field level seats to sign autographs and chat with the fans. Other fans had begun to leave. Patrons who had arrived by subway received lifts from friendly drivers.14

After a fruitless 75-minute wait for the lights to go back on, the game was suspended.

The Cubs returned to their hotel, the Waldorf Astoria, by bus. The hotel provided them with candles for the climb to their rooms. Burris’s candle blew out as he reached his floor, the 16th. Burris said later he was “scared to death,” and didn’t know “if there was someone hiding in the hallway.” With the air-conditioning not working, Burris didn’t get much sleep.15 Without lighting, the long trek to the ground floor with luggage had to be completed the following day, as the Cubs were due in Philadelphia for a doubleheader Friday night.

The electricity needed to power Shea Stadium came on at about 10 the next morning, in time for the Mets and Cubs to play their scheduled day game. Fans were admitted to the ballpark at 11:45 A.M., but the power went out again at 11:53, and the game was postponed. Only after 25 hours would power be restored.16 The two games were rescheduled for September 16, the next time the Cubs would be in New York.17 The Cubs made it to Philadelphia, where they lost two games on Friday.

The months until September were not kind to the Cubs. They won only 24 of 62 games played before their return to Shea Stadium on September 15 with a 76-70 record, in fourth place in the National League East, 15 games behind the Phillies. Coincidentally, the Mets had also won 24 games (out of 61) during this time frame.

When the suspended game resumed on September 16, with one out in the bottom of the sixth, the Mets made three lineup changes and the Cubs one, but Koosman and Burris were back on the mound. The Mets tied the game in the seventh when pinch-hitter Ed Kranepool singled home first baseman Bruce Boisclair, but the Cubs surged back in front to stay in the eighth. Larry Biittner walked, and Koosman’s second wild pitch of the game moved him to second. One out later, Gene Clines singled Biittner to third. Catcher Steve Swisher’s two-out single drove in Biittner and Clines to make it 4-2, Cubs. They added an insurance run in the ninth on a run-scoring single by Murcer off reliever Skip Lockwood — only the third pitcher to see action in the game — to make it a 5-2 final.

Koosman would end up with 13 strikeouts and his 19th loss of the year. Burris improved to 13-15. The time of the game was 2 hours 40 minutes … and 65 days.

Author’s Note

I was a college student home for summer break and living on 26th Street in Manhattan. I traveled to the game by subway. Sitting in the upper deck when the blackout occurred, I looked west to where the Manhattan skyline would normally be visible and to my astonishment saw nothing, illustrating the scope of the blackout. I immediately panicked. My first thought was: How the hell would I get back to Manhattan? The less attractive alternative would have been to figure out how to get to the home of my stodgy and seemingly “ancient” (to a 20-year-old kid) Cuban relatives, who lived in Bayside, several miles to the east.

I got a ride back to Upper Manhattan and walked down from the highway to street level at 178th Street, where looting was occurring. Two free buses got me to within 15 blocks of my apartment. I then walked down the middle of Lexington Avenue to my building, went up the stairwell with the superintendent and felt my way to my apartment, which was the unit most distant from the elevator.

Sources

The author used Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet for information about in-game events.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYN/NYN197707130.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1977/B07130NYN1977.htm

Notes

1 https://thestarryeye.typepad.com/weather/2012/07/looking-back-at-new-york-weather-july-13.html, retrieved November 28, 2020.

2 Seaver later said he demanded a trade from the Mets after a Young column reported that Seaver was jealous of former teammate Nolan Ryan, who was making more money. The column mentioned Seaver and Ryan’s wives, and Seaver resented what he considered an attack on his family. The column in question was “Don: See Light … Reconsider,” New York Daily News, June 15, 1977: 88.

3 The Mets received outfielders Dan Norman, 22, and Steve Henderson, 24; infielder Doug Flynn (.255 lifetime batting average, 7 career home runs, lifetime OPS+ of 58); and pitcher Pat Zachary, 69-67 lifetime record, career ERA+ of 102, or 2 percent above league average.

4 Author phone interview with Jerry Koosman on December 4, 2020.

5 Paul L. Montgomery, “Night and Day, Mets Are Blacked Out,” New York Times, July 15, 1977: D9.

6 Patrick Sauer, “Blackout At Home: When the Lights Went out at Shea Stadium in 1977,” Vice Sports, https://www.vice.com/en/article/kzan8w/blackout-at-home-when-the-lights-went-out-at-shea-stadium-in-1977, retrieved December 20, 2020.

7 Vice Sports web article.

8 Montgomery, “Night and Day, Mets Are Blacked Out.”

9 Jack Lang, “Fans Sing ‘White Christmas’ in Hot, Dark Shea,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1977: 23.

10 Montgomery, “Night and Day, Mets Are Blacked Out.”

11 Montgomery, “Night and Day, Mets Are Blacked Out.”

12 Montgomery, “Night and Day, Mets Are Blacked Out.”

13 Lang, “Fans Sing ‘White Christmas’ in Hot, Dark Shea.”

14 The author arrived at this game via subway and did get a lift back to Upper Manhattan from a New Jersey family.

15 Vice Sports, vice.com/en/article/kzan8w/blackout-at-home-when-the-lights-went-out-at-shea-stadium-in-1977.

16 Associated Press, “New York Reels from Massive Blackout, Eugene (Oregon) Register-Guard, July 14, 1977: 1A. https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=uKNVAAAAIBAJ&pg=6168,3215678&hl=en, retrieved December 12, 2020.

17 Montgomery, “Night and Day, Mets Are Blacked Out.”

Except for those articles listed with a different retrieval date, all articles were retrieved from the internet on November 28 or November 29, 2020.

Additional Stats

Chicago Cubs 5

New York Mets 2

Shea Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.