June 13, 1921: Heinie Groh returns from holdout with two hits; Reds lose to Brooklyn

bottle bat 1. A baseball bat with an especially thick barrel, an abrupt taper, and very thin handle, which gives it a milk bottle-like appearance. — The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, Third Edition.1

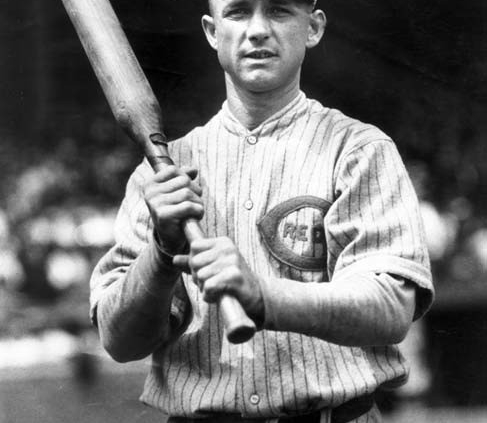

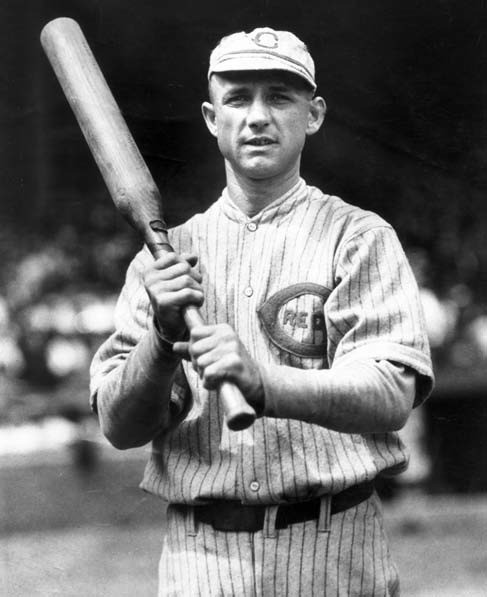

When the diminutive Heinie Groh, all 5-feet-8 and 158 pounds, came to the plate, he brought a bat of unusual proportions and a batting stance even more unconventional. Groh was a utility player for the New York Giants in 1912 when manager John McGraw suggested that a bat with a bigger barrel might help him improve his hitting. Groh’s problem was that he had small hands, so A.G. Spalding and Brothers created a bat with a thicker barrel for better contact and a thinner handle for better grip. As for the batting stance, Groh positioned himself at the front of the batter’s box with both feet facing the pitcher. Groh’s size helped him create a smaller strike zone to get on base any way he could — slapping a hit, executing a hit-and-run, or drawing a lot of walks.2

When the diminutive Heinie Groh, all 5-feet-8 and 158 pounds, came to the plate, he brought a bat of unusual proportions and a batting stance even more unconventional. Groh was a utility player for the New York Giants in 1912 when manager John McGraw suggested that a bat with a bigger barrel might help him improve his hitting. Groh’s problem was that he had small hands, so A.G. Spalding and Brothers created a bat with a thicker barrel for better contact and a thinner handle for better grip. As for the batting stance, Groh positioned himself at the front of the batter’s box with both feet facing the pitcher. Groh’s size helped him create a smaller strike zone to get on base any way he could — slapping a hit, executing a hit-and-run, or drawing a lot of walks.2

It all seemed to work for Groh after he was traded to Cincinnati in 1913.3 Groh hit over .300 four times in the next nine seasons and averaged twice as many walks as strikeouts. Led by the bats of Groh and Edd Roush, the Reds won the National League pennant in 1919 and subsequently the World Series against the Chicago White Sox of Black Sox Scandal notoriety.

He was superb as a third baseman during that same period, leading the league six times in double plays, twice in fielding percentage and three times in putouts. With a career .967 fielding percentage, he was arguably the best third baseman of the Deadball Era (prior to 1920).

Before the 1921 season, both Groh and Roush became embroiled in a bitter salary dispute with Cincinnati owner Garry Herrmann.4 Groh wanted a $2,000 raise and would accept his current salary of $10,000 only if he were traded to another team. Groh remained steadfast as the season began without resolution, declaring that he would not play another game with the Reds.5 Roush returned to the lineup on May 1.

When the New York Giants made an offer to Cincinnati for cash and players, Groh signed his contract with the Reds in early June fully expecting to be reinstated by the commissioner and then traded.6 Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis clearly understood that the Reds intended to immediately trade Groh and would have nothing of it. “The suggestion that the hold-out process may disqualify a player from giving his best service … is an idea that will receive no hospitality here. It is at war with the ABC’s of sportsmanship and impugns the integrity of the game itself.”7 Groh could play only for the Reds in 1921.

Newspaper reports suggested that Groh was conflicted by the turn of events. As the Reds were finishing up a series hosting the Giants on June 10, Groh worked out at third base before the game, but sat in the dugout thereafter. He appeared to accept the Landis decision “with good grace, although he was disappointed to a certain extent.”8

Two days after Landis’s ruling, the defending National League champion Brooklyn Robins came into town for a four-game series against the Reds beginning June 11.9 Jack Ryder, reporting for the Cincinnati Enquirer, wrote that Groh refused to play in the opening game of the series.10 The next day Ryder reported that “Heinie Groh experienced a change of heart overnight and reported for duty yesterday.”11

Finally, two months after Opening Day,12 Groh was in the lineup for the third game of the series, batting seventh and playing third base. To accommodate Groh’s return, Reds manager Pat Moran shuffled his crowded infield, shifting Sam Bohne from third to second and sitting rookie Lew Fonseca. The Reds had won the first two games against Brooklyn with relative ease. After all, the Robins committed eight errors in two games, scored only one run and now had a six-game losing streak.

Manager Wilbert Robinson chose Leon Cadore to start for the Robins. Always a Brooklyn fan favorite, Cadore (1-7, 5.85 ERA) was having a tough 1921 season. He was a 15-game winner for the 1920 pennant-winning Robins and will always be remembered for his 26-inning complete-game performance in baseball’s longest game that May.13 Moran started Lynn Brenton (0-4, 3.67 ERA), whose major-league career would be over in less than a month’s time. The Reds were 20-32, languishing in the unusual territory of seventh place.

The Robins got off to a quick start against Brenton. After Ivy Olson struck out, Jimmy Johnston walked and advanced to second on a groundout. Johnston scored when Zack Wheat tripled to right. Ed Konetchy walked, putting runners on first and third. Brenton thought that first baseman Jake Daubert was holding the runner near the bag, but he wasn’t and a balk on a halted throw gave the Robins a 2-0 lead.

In the bottom of the first with one out, Daubert reached base on an error by Robins shortstop Ivy Olson. Brooklyn fans had to wonder whether this error-filled series was going to continue as in the first two games. It didn’t. Rube Bressler hit into a double play, the inning was over, and the Robins played errorless baseball thereafter.

What did happen had to be frustrating for Cincinnati fans. In each of the next five innings, the first Reds batter reached base with a hit; yet they failed to score, including after Groh’s first hit of the season in the fifth.

The Reds finally broke through in the seventh inning. Groh’s second hit of the afternoon also with the willow — a baseball bat of light soft wood good for bunting and swinging with speed14 — got things started. He advanced to third when Ivey Wingo singled to right. Bubbles Hargrave pinch-hit for Brenton but lined to short for the first out. Bohne doubled to right to score Groh and reliever Al Mamaux was brought in to replace Cadore on the mound. A short fly to left and a strikeout ended the threat with the Robins still leading 2-1.

The Reds tried to score again in the eighth against Mamaux. Thomas S. Rice of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on Pat Duncan’s one-out fly to short right-center “which Hood or Myers could have taken, but they did an Alphonse and Gaston and the ball fell for a two-bagger.”15 When Larry Kopf walked, Groh came to the plate in another scoring opportunity for the Reds. A rather easy third-to-first double play ended the threat.

The Robins played for an extra run in the ninth. Wheat opened with a single to left off reliever Fritz Coumbe, advanced to second on Konetchy’s sacrifice, and moved to third on Hi Myers’ single to short center field. When Pete Kilduff’s groundout forced Myers at second, Wheat scored the third and final Robins run. That run may have influenced the Reds’ strategy in the bottom half of the inning.

For all the frustrations endured by the Reds and their fans through the first eight innings — 10 hits and only one run to show for it — they were still very much alive batting in the ninth. Pinch-hitter Charlie See opened with a single to left. Two things happened when right fielder Wally Hood lost Bubbles Hargraves’ fly ball in the sun. Hargraves ended up on second with a double; Hood was immediately replaced in the field by Bernie Neis.16

Surely the Reds could score with no outs and runners on second and third. No. Mamaux struck out Bohne and got Daubert on a popout to the catcher. When center fielder Hi Myers made a circus catch on Bressler’s potential triple, the game was over and so was the Robins’ losing streak.17

Of course, the day belonged to Heinie Groh and his return with two hits off the bottle bat, solid play in the field and a warm welcome from Cincinnati fans. True, the game had been frustrating for the home team — runners on base in every inning, outhitting the Robins 12 to 7, and scoring only one run, by Groh himself. Harold E. Russell’s cartoon in the Cincinnati Enquirer brought some levity to the circumstances: “The Reds socked twelve hits, but they are as useless as a fur lining in a bathtub so far as final results are concerned.”18

Groh batted .331 in his shortened season and finally got his wish. In December he was traded to the New York Giants for outfielder George Burns, catcher Mike Gonzáles and cash.19 Groh also got his salary raise when he signed his 1922 contract with the Giants—$12,500.

Groh never batted .300 again but with bottle bat in hand, his 1922 World Series-best .474 batting average helped the Giants sweep the Yankees in five games for the title.20 That average, like his bat, followed Groh everywhere. Years later, Groh put it clearly, “I still carry 474 as my license plate on my car. Have every single year since 1922, as a matter of fact.”21

Author’s note

The history and design of bats, rules regarding their use, and the physics associated with hitting a baseball have all been the subject of scholarly research and writing by SABR authors.22 These works all have one thing in common: their reference to Heinie Groh and his bottle bat.

Researching a game that took place 100 years ago was a new experience for this author. Always an active user of The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, the author discovered other baseball vocabulary in newspaper accounts.23 Some examples follow.

- hillock: synonym for mound.

- scoring disk: home plate

- pickle: “a play in which a baserunner is caught in a rundown between bases.”24

- chukker: synonym for inning.

- bingle: “a base hit of any kind.”25

Sources

The author accessed Baseball-Reference.com for box scores/play-by-play information (baseball-reference.com/boxes/CIN/CIN192106130.shtml), and other data, as well as Retrosheet.org (retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1921/B06130CIN1921.htm).

Notes

1 Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3rd Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 128.

2 Sean Lahman, “Heinie Groh,” SABR Baseball Biography Project.

3 On May 22, 1913, Groh was traded by the Giants with Red Ames, Josh Devore, and $20,000 to Cincinnati for Art Fromme. In the very last paragraph of its story, the New York Times reported that “Groh is a most promising player, but Manager John McGraw could find no place for him on his present team.” (“Giants Get Pitcher Fromme in a Trade,” New York Times, May 23, 1913: 11)

4 Pitcher Ray Fisher was also unhappy with his salary and chose to leave the Reds after pitching in the final exhibition game to become the baseball coach at the University of Michigan. The details are discussed extensively by SABR author Chip Hart (Chip Hart, “Ray Fisher,” SABR Baseball Biography Project).

5 “Groh ‘Quits’ Team,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 7, 1921: 10.

6 Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills, Baseball: The Golden Age (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971).

7 “Groh Reinstated; Cannot Be Traded,” New York Times, June 10, 1921: 19.

8 Jack Ryder, “Southpaw Hangs It On Giants,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 11, 1921: 6.

9 The Brooklyn franchise officially became known as the Robins in 1913. Earlier names, the Superbas (1899-1910) and the Dodgers (1911-1913), were still being used in 1921 in many media reports, including those referenced in this essay.

10 Jack Ryder, “Cuban Holds ’Em Hitless,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 12, 1921: 19.

11 Jack Ryder, “Another Win Is Added to String,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 13, 1921: 18.

12 John Fredland, “April 13, 1921: Reds surge in eighth inning, beat Pirates on Opening Day,” SABR Baseball Games Project.

13 Wayne Corbett, “May 1, 1920: An extreme exercise in futility: Braves, Dodgers play 26 innings to no decision),” SABR Baseball Games Project. Joe Oeschger also pitched a complete game for the Boston Braves in that 1-1 tie.

14 Dickson, 935. Willow was used in the New York Times account of the game. The word derives from its first use to describe cricket bats of similar properties to early baseball bats.

15 Thomas S. Rice, “Superbas Check Slump; Fans Find Consolation in Giants’ String of Defeats,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 14, 1921: 24. Alphonse and Gaston was an American comic strip by Frederick Burr Opper that first appeared in the New York Journal on September 22, 1901. “Said of an act, play, base hot, error, or fielding situation in which one or more players defer to one another, often allowing the ball to drop to the ground in the process.” [Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3rd Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 14].

16 Rice.

17 Rice.

18 Harold E. Russell, “And Yet They Lost!” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 14, 1921: 6.

19 Jack Ryder, “Big Deal Put Over by Reds,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 7, 1921: 14; “Fans Seemed Pleased Over Deal Put Over Bringing George Burns to Reds,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 7, 1921: 14. There is some discrepancy in the reports of the cash involved in the trade—New York Times: $50,000-$100,000; Cincinnati Enquirer: $100,000; Baseball-Reference.com: $150,000.

21 Lawrence S. Ritter, The Glory of Their Times (New York: Macmillan and Company, 1966), 299.

22 Jim Kreuz, “Stealing First Base,” Baseball Research Journal,, Summer 2010: 35; Ben Walker, “Properties of Baseball Bats,” Baseball Research Journal, Summer 2010: 113; Steven Bratkovich, “The Bats … They Keep Changing!” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2018: 40.

23 “Heinie Groh Back, but Redlegs Lose,” New York Times, June 14, 1921: 11. Jack Ryder, “Champions Stop Red Streak,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 14, 1921: 6. Thomas S. Rice, “Superbas Check Slump; Fans Find Consolation in Giants’ String of Defeats,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 14, 1921: 24.

24 Dickson, 635.

25 Dickson, 109.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Robins 3

Cincinnati Reds 1

Redland Field

Cincinnati, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.