May 8, 1901: Boston wins first home game in Red Sox franchise history

“The diamond shone in the sun like a great canvas of freshly spread green paint, the uniforms of the home team were as spotless as a just-from-the-wrapper ball and the great crowd seethed with good nature. It was the birth of a major-league baseball club for Boston.” – Boston Globe1

No one would know them as the Red Sox until mid-December 1907. They wore blue stockings until the 1908 season. But the May 8, 1901, game between the Boston Americans and Philadelphia Athletics was the first regular-season home game in franchise history. The Boston Globe headline read: “AMERICAN LEAGUE MEN GIVEN ROYAL WELCOME BY 11,500 ROOTERS. Auspicious Christening of Huntington Av. Grounds — Philadelphias Prove Easy Victims — Local Team Strikes a Winning Gait.”

No one would know them as the Red Sox until mid-December 1907. They wore blue stockings until the 1908 season. But the May 8, 1901, game between the Boston Americans and Philadelphia Athletics was the first regular-season home game in franchise history. The Boston Globe headline read: “AMERICAN LEAGUE MEN GIVEN ROYAL WELCOME BY 11,500 ROOTERS. Auspicious Christening of Huntington Av. Grounds — Philadelphias Prove Easy Victims — Local Team Strikes a Winning Gait.”

The 1901 Boston Americans had 10 games under their belt before their first home game. They had played two games in Baltimore, four in Philadelphia, and four in Washington, and had a record of 5-5. They’d lost the first three games but were coming to Boston with a three-game winning streak.

The Boston Cadet band played for an hour before the game, entertaining the 11,000 spectators who turned out for the first game ever played at the new Huntington Avenue Grounds. All seats were filled and a number of fans watched the game from behind ropes in both left and right field. A ball hit into the crowd was to be a ground-rule triple.

There was an innovation for Boston baseball — a “megaphone man” (Charles Moore), who “announced the batteries to all parts of the field, and kept the patrons posted on changes in the teams.”2

The attendance was particularly impressive because Boston’s National League team — one that had been very successful throughout the 1890s — “flooded the city with free admission ,”3 hoping to cut down the crowd for the upstart American League club debuting the same day the Beaneaters were hosting Brooklyn at the nearby South End Grounds, which was “literally on the other side of the (New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad) tracks.”4 The Beaneaters filled the South End Grounds for an exciting 7-6 victory in 12 innings, but the paid attendance was just 5,500.5

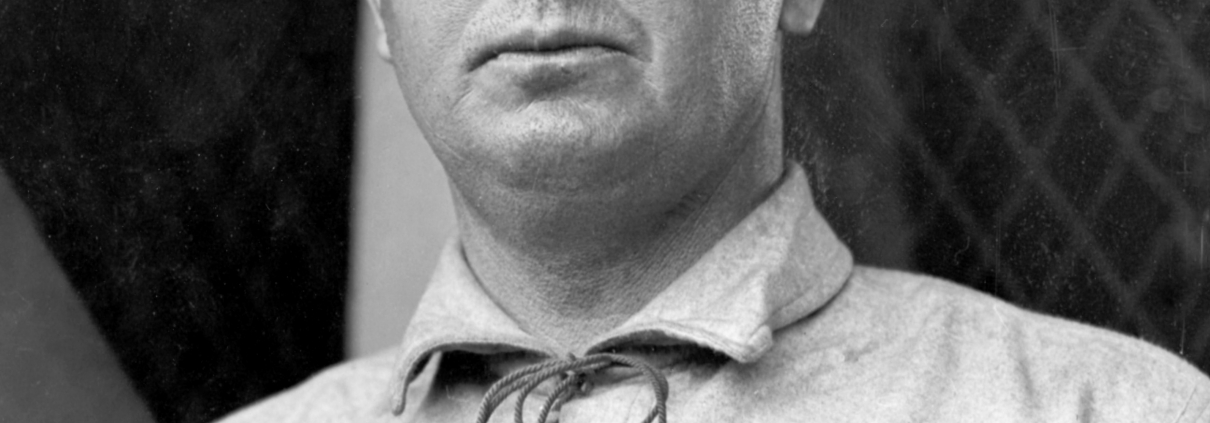

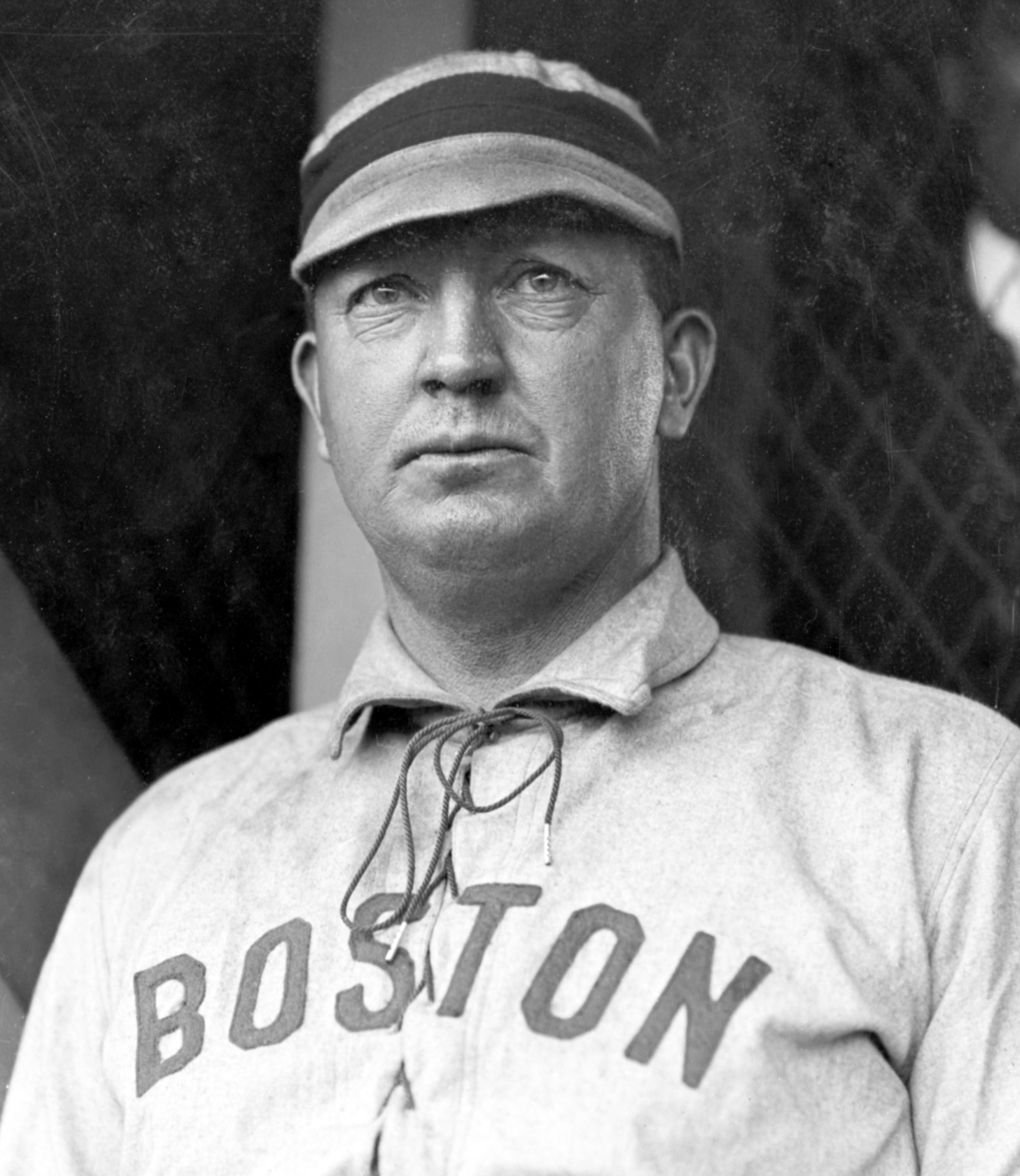

Cy Young was the starting pitcher for Boston. He had jumped to the American League after 11 seasons — the last 10 with 20 or more wins — in the National League. Though he had often pitched against the Beaneaters for the National League’s Cleveland Spiders and St. Louis Cardinals, the Boston Post correspondent saw fit to describe him: “Cy looks rather like an ungainly fellow when working, but his awkwardness proved no bar to his pitching prowess before which the Philadelphia Athletics had to surrender unconditionally.”6

Philadelphia’s starter, right-hander Bill Bernhard, was 15-10 in 1900 for the National League Phillies but signed with the city’s American League entry for 1901. The Phillies were fighting Bernhard’s departure; as of game time, ownership’s bid to bar him from the new league — along with star second baseman Nap Lajoie and pitcher Chick Fraser — was pending before a Pennsylvania court.7

Young held Connie Mack’s Athletics scoreless in the top of the first. Right fielder Jack Hayden grounded to Boston team captain Jimmy Collins at third base and Young struck out center fielder Phil Geier. Dave Fultz singled, but catcher Lou Criger threw him out when Fultz tried to steal second base.

Boston left fielder Buttermilk Tommy Dowd singled to left field off Bernhard in the first. Right fielder Charlie Hemphill promptly laid down a bunt to try to move him to second, and both runners were safe when third baseman Lave Cross fumbled the bunt. Chick Stahl did sacrifice, advancing both baserunners. Jimmy Collins singled and Dowd scored with the first run.

Buck Freeman followed with the Huntington Avenue Grounds’ first-ever home run. His hit soared over Geier’s head in center field — the only section of the outfield lacking a roped-off crowd to transform a long hit into a ground-rule triple. Hemphill and Collins scored ahead of Freeman. It was 4-0, Boston.

Young didn’t allow a run for any of the first five innings, while Boston scored in each one.

Boston added one run in the second inning. Young singled. So did Dowd. Hemphill again bunted safely, and the bases were loaded. Stahl flied out to Fultz in left field and Young tagged and scored.

With two outs in the third inning, second baseman Hobe Ferris scored Boston’s sixth run of the game. Newspaper reports of his run varied. The Boston Herald reported that Ferris singled to right and ran all the way around the bases due to an error by right fielder Hayden and catcher Doc Powers’ “failure to stop the ball thrown from the outfield.”8

But both the Boston Globe and Boston Post reported three base hits in the inning, with the Globe’s account reading, “Freeman opened with a single, only to be thrown out when trying to steal second. Freddy Parent got first on Hayden’s muff. Ferris singled and Criger put one in a safe spot, scoring Ferris.”9 Regardless, the Americans had pushed their lead to 6-0.

In the Boston fourth inning, Hemphill tripled to center field. Stahl beat out an infield roller to first base when Bernhard failed to cover the bag. Bernhard was “too tired,” averred the Herald. Hemphill held at third on the play. Stahl had to leave the game; he had somehow fractured a rib and was replaced as a baserunner by Charlie Jones.

Hemphill scored when Collins hit a fly ball to left field. Freeman followed with a triple, driving in Jones and putting a runner back on third base. The Boston Post said Freeman’s drive would have been a home run without the outfield crowd and the ground rule that a ball hit into the crowd would be scored a triple.10

On Parent’s grounder, Philadelphia tagged out Freeman in a rundown, but he prolonged the rundown long enough for Parent to get all the way to third base. Ferris singled Parent home. Three more runs had been added and the score stood 9-0.

That total was boosted to 11-0 in the fifth. Young tripled. Dowd tripled. Charlie Jones, who had taken over for Stahl in center field, flied out to center, allowing Dowd to tag and score.

Neither side scored in the sixth.

The Athletics got on the board in the top of the seventh. Shortstop Harry Lochhead hit the ball to his counterpart, Parent, and reached first on a fielding error. He moved up on an out by Powers and scored on Hayden’s single.

Not willing to let the run go unanswered, Boston scored once more in the bottom of the seventh. Hemphill doubled. He moved to third base on an out by Jones and crossed the plate on a single by Collins. This made it 12-1.

Philadelphia got three runs in the eighth. Fultz and Lajoie both singled. They scored on a three-base hit by first baseman Socks Seybold. Seybold scored on Cross’s fly to center field. There was no more scoring from either side, the final coming to 12-4.

It was a game of hitting, and errors. There was only one walk in the game, allowed by Bernhard. There were only two strikeouts, both by Young. Boston had 22 base hits and committed three errors.11 Hemphill was 4-for-4. Freeman was 3-for-5 and had five runs batted in. Mack’s Athletics had 11 hits but made five errors.

In something of an understatement, the Philadelphia Inquirer acknowledged that Bernhard “was not at his best” and, the paper continued, “had to stand a severe pumping for eight innings.”12

The Boston Globe was not as kind: “The game was one of the poorest ever played in this city by the visiting team. The home team hammered the weak pitching all over the field until the crowd cried to have Bernard [sic] taken out. The home team put up a good all-round article of ball. The work of the Quakers was worth about 3 cents on the dollar.”13

Echoes of the Game

The Boston Globe offered some “Echoes of the Game,” which provided additional observations on the day, and we will offer a few here:

Among other new things was the shrinkage in the bags of peanuts and the new style of slam-banging them into the bleachers when a purchaser high up on the benches tossed down a nickel. That was half the fun. Money was thrown away for the sport of seeing the swiftly-thrown bags burst.

Backward as the season is, six straw hats in all the jauntiness of a cocked-on-the-side position, loomed up amid the sea of soft felts and hard derbies. In striking contrast was the millinery of the ladies, which, sprinkled amid the black, brown, gray and white somberness of the male head covering, warmed up the interior of the grand stand and seemed to rob the east wind of half its chill.

Just a dash of Tabasco was thrown into the game before the final inning, and the visitors saved themselves from a bad defeat.

Arthur Dixwell, seated down among the scorekeepers and telegraph operators, wafted memory back to the days when sensational plays and close finishes were greeted with cracker snapping “hi hi’s.”

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and the following:

Nowlin, Bill, ed. New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans (Phoenix: SABR, 2013)

Nowlin, Bill. Red Sox Threads (Burlington, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2008)

baseball-reference.com/boxes/BOS/BOS190105080.shtml

retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1901/B05080BOS1901.htm

Notes

1 “American League Men Given Royal Welcome by 11,500 Rooters,” Boston Globe, May 9, 1901: 4.

2 “Eleven Thousand See Collins’ Team Beat the Athletics, 12 to 4,” Boston Herald, May 8, 1901: 8.

3 “Athletics Open Boston Grounds, but Are Beaten,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 9, 1901: 6.

4 Bob Ruzzo, “South End Grounds,” SABR BioProject, at https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/south-end-grounds-boston/.

5 The American League team priced its tickets throughout 1901 at half what the Beaneaters had been charging.

6 “Boston Americans Cheered to Victory,” Boston Post, May 9, 1901: 5.

7 On May 17 — nine days after this game — Pennsylvania’s Court of Common Pleas denied the Phillies’ request for injunctive relief, allowing Bernhard, Lajoie, and Fraser to play for the Athletics. All three remained in the American League for the rest of the 1901 season. After the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overruled the trial court in April 1902 and directed that Lajoie — without mentioning the two pitchers — be barred from the American League, Lajoie and Bernhard signed with the American League’s Cleveland Bronchos and remained there after other state courts disagreed with Pennsylvania’s ruling. Fraser returned to the Phillies. SABR member C. Paul Rogers III provided a thorough discussion of this case in a 2002 SMU Law Review article. C. Paul Rogers III, “Napoleon Lajoie, Breach of Contract and the Great Baseball War,” 55 SMU Law Review 325 (2002).

8 Boston Herald.

9 Boston Globe.

10 Boston Post.

11 The number of hits by Boston batters was perhaps more impressive in that the players were tired after the trip from Washington the day before — a “long and tiresome journey, with no refreshment and without their own bats.” See Boston Post.

12 “Athletics Open Boston’s Grounds, but Are Beaten,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 9, 1901: 7.

13 Boston Globe.

Additional Stats

Boston Americans 12

Philadelphia Athletics 4

Huntington Avenue Baseball Grounds

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.