October 10, 1926: Pete Alexander saves the day

The seventh game of the 1926 World Series between the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees was played on a cold, damp day in New York City. Rain had fallen during the night and a steady drizzle continued throughout the morning threatening a postponement. However, about noon the rain stopped and conditions improved enough to go ahead with the game as planned. When the first pitch was thrown two hours later 38,093 eager baseball devotees, a small crowd by Yankee Stadium standards, had pushed through the turnstiles.

On the mound for the Yankees that day was Waite Hoyt. At times during the season he had pitched excellently. On other occasions he had a difficult time lasting more than a few innings. Meanwhile the Cardinals sent their ace, Jesse “Pop” Haines, to the mound. Haines had missed several weeks early in the season with an injury but finished the campaign with a fine 13-4 record.

Hoyt got off to a good start allowing only two hits through the first three innings. Haines’s start was less impressive. When he came to the plate in the first inning, all eyes were on Babe Ruth. Cardinals pitchers had been instructed by player-manager Rogers Hornsby to pitch around the Babe. Haines did, walking Ruth. Bob Meusel followed with a single but the Yankees were unable to score. Haines gave up another two hits in the second but avoided more trouble when catcher Bob O’Farrell gunned down “Jumpin’” Joe Dugan as he attempted to steal second. Despite the Cardinal “Ruth strategy,” in the third the Bambino walloped a two-out shot into the right-field bleachers scoring the game’s first run.

Down a run in the fourth, the Cardinals — with considerable help from the Yankees defense — mounted an attack of their own. “Sunny” Jim Bottomley got it started with a one-out single to left. Third baseman Les Bell followed with what looked like an inning-ending double-play ball but shortstop Mark Koenig let the ball bounce off his glove. Chick Hafey followed with a sharp single to left, loading the bases. O’Farrell then lifted a routine fly ball to the outfield. Left fielder Meusel positioned himself under the ball, reached up to make the catch, but let the ball plunk off his glove. Bottomley scampered home with the tying run. With the bases still loaded, shortstop Tommy Thevenow punched a pitch into right field scoring two more runs. Hoyt then struck out Haines and got Wattie Holm to ground one to shortstop. This time Koenig made the play ending the inning but the Cardinals had scored three unearned runs.

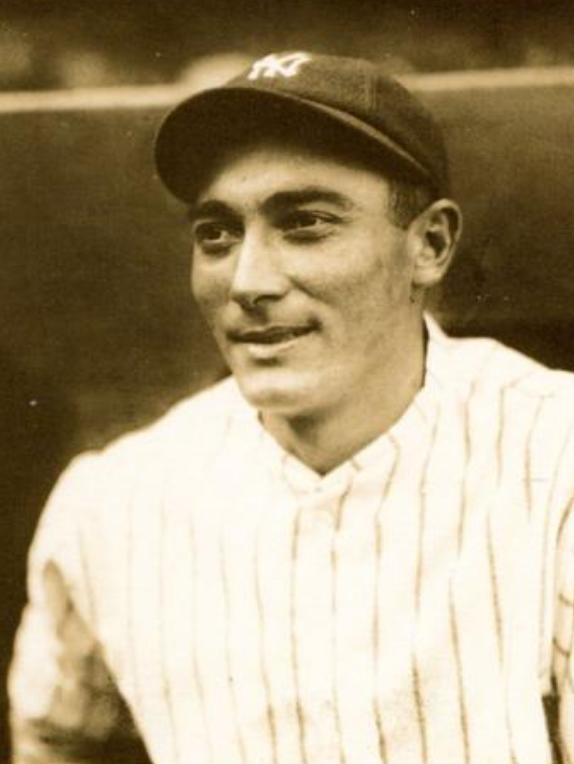

Haines got through the fourth allowing only a walk to Lou Gehrig. In the fifth the Yankees put two more men on base via a single by Earle Combs and another walk to Ruth but failed to score. The Cardinal hurler’s struggle continued in the sixth when the Yankees scored a second run on hits by Dugan and Hank Severeid.

The Yankees’ half of the seventh proved to be three outs for the ages. It started with a single by Combs, a sacrifice bunt by Koenig, and a four-pitch walk by Ruth. Meusel then bounced one to third baseman Bell who got the force out at second. Clearly struggling, Haines’s next four pitches to Gehrig were alarmingly far out of the strike zone. Concerned, Hornsby called time and trotted from second in to talk to his ace. Five days earlier in Game Three a throw-back from his catcher had smashed the tip of the index finger on Haines’s pitching hand. The next day the finger was swollen, badly bruised, and the nail was bloody. Hornsby knew about the freak accident and checked on Haines between innings. Each time Haines had assured his manager that he was all right. Finally in the seventh Haines admitted he could go no further.

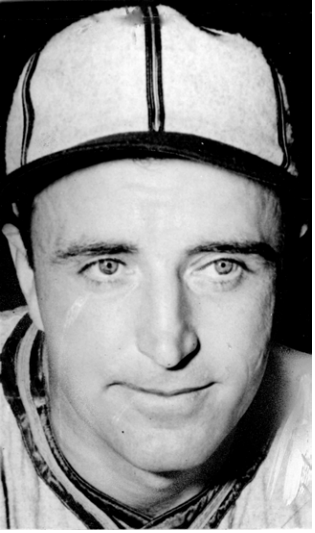

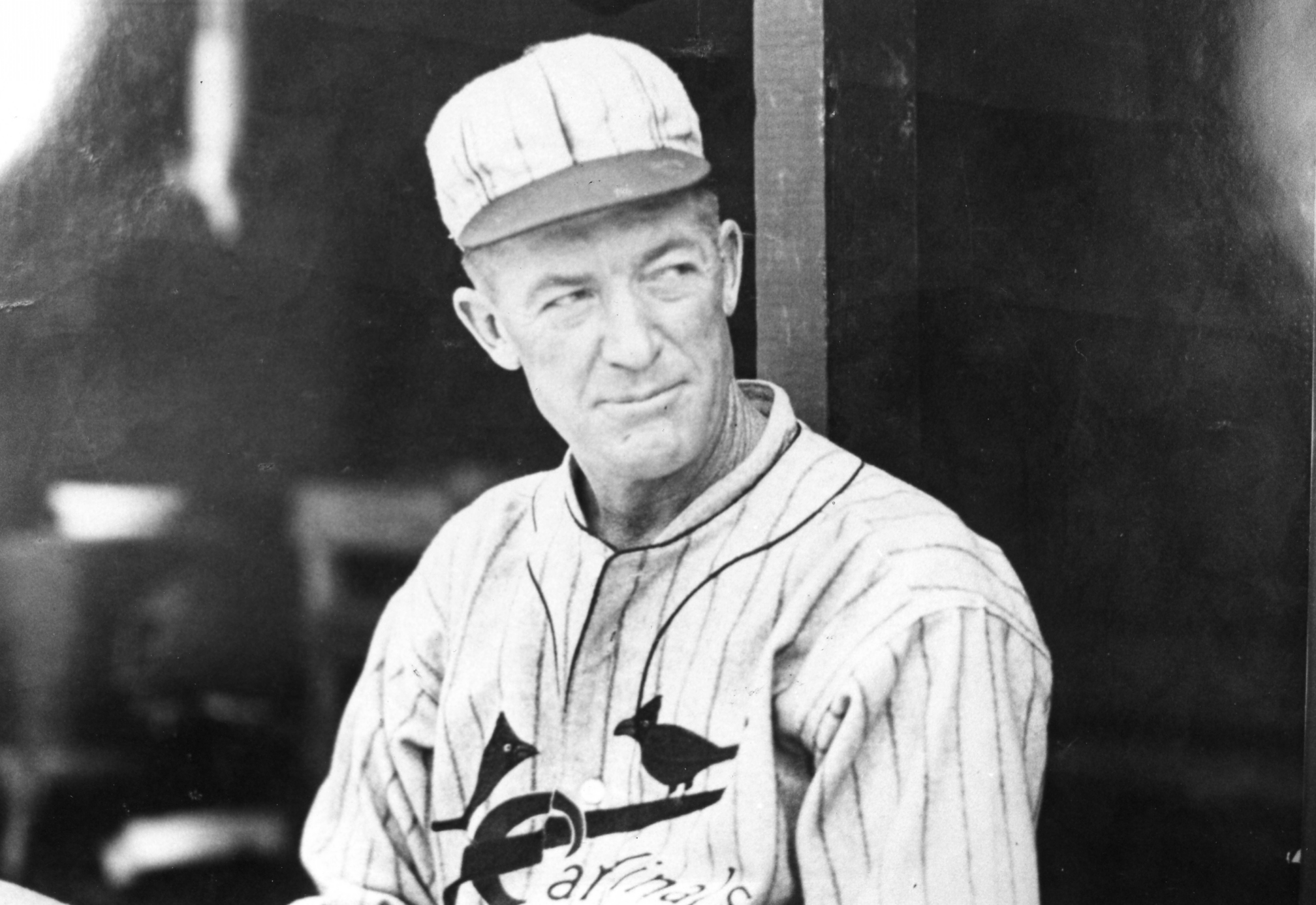

For Hornsby the question became who to call in to relieve. The only member of the Cardinals staff that seemed unavailable was Grover Cleveland Alexander, who had pitched a complete game the previous day winning for the second time in the Series. Once one of the best pitchers in the game, “Old Pete” was in the twilight of his illustrious career. He was also a confirmed alcoholic and everyone assumed that he had celebrated his previous day’s big win by drinking into the early morning hours. Clearly he would not be ready to face the Yankees again.

Standing amidst gloomy late afternoon shadows that darkened the cavernous stadium, Hornsby knew exactly who he wanted on the mound and waved to the bullpen. Through the cold, misty fog that had descended upon the field all eyes strained to see his choice. After a minute or so the hushed fans watched as the gate to the Cardinals bullpen opened and the grey silhouette of a solitary figure emerged onto the playing field. The new pitcher appeared a bit stooped. He was wearing a red Cardinals sweater and had his cap tilted a bit to one side. As he slowly ambled across the outfield grass he touched gloves with left-fielder Holm and a few seconds later did the same with shortstop Thevenow. By the time he reached Hornsby at the edge on the infield the whispers that had been circulating throughout the stadium became a low roar. “It’s Alexander…’Alex the Great’!” “Does Hornsby really want ‘Old Alex’?”

Reporters after the game claimed that when he took the ball from Hornsby, Alexander was well lubricated and suffering from a long night of drinking. The truth is that Alexander was completely lucid and in control of himself. After Game Six Hornsby had told him to limit his celebrations because he might have to pitch in relief the next afternoon in Game Seven. Alex abided by his manager’s instructions.

Waiting at the plate was young Tony Lazzeri, who had smacked 18 homers and driven in 117 runs during the season. Alexander told his manager that he planned to set Lazzeri up with inside fastballs and then break a curve or two over the outside part of the plate. Hornsby, who would have told any other pitcher how to pitch, instead simply nodded and gave Alexander the ball.

With Combs on third, Meusel on second, and Gehrig on first Alexander started Lazzeri off as planned, a fastball high and inside for ball one. Working quickly and with no windup the wily veteran brought the next pitch, another fastball, down across the inside corner of the plate for a strike. He took a little off the third offering but delivered it close to the same spot as the previous pitch. As Alexander had predicted he would, Lazzeri swung hard at the pitch lifting it deep down the left-field line. Hornsby at second watched, fearing the worst. The Yankees bench jumped on to the dugout steps as the ball climbed toward the left-field bleachers. All 38,093 in the stands leapt to their feet, most of them certain that the young slugger had knocked one out of the park. And then as it sped toward the fence the ball began to bend just a bit to the left. It returned to earth well beyond the fence but a few feet in foul territory — nothing more than a long second strike. On the mound Alexander, as calm as ever, ended the drama just as he had promised: a tantalizing curve low and outside. Lazzeri took the bait. He swung hard but completely missed the ball. The immediate Yankees threat was over but there were still two innings to play.

Herb Pennock, who had replaced Hoyt an inning earlier, gave up two hits in the eighth but the Cardinals were unable to score. In the bottom half of the inning Alexander set down the side in order. Pennock did the same in the top of the ninth.

As he took the mound in the bottom of the ninth, Alexander knew that Babe Ruth was the third scheduled Yankee hitter. Two quick outs later, Ruth came to the plate. Alexander started the Bambino with the first strike Ruth had seen since his third-inning home run. A ball and a foul second strike left the Cardinals one pitch away from their first world championship but the next three pitches all missed the plate and Ruth, for the fourth time in the game, walked to first.

With Ruth on first, Meusel came to the plate with a chance to redeem himself for his crucial 4th inning error. The Yankees left fielder was the only hitter who had consistently given Alexander problems. In the seven times the two had faced each other during the Series Meusel had three hits including a double and a triple the previous day. As Alex released his first pitch to Meusel, a strike, Ruth made his bet. He inexplicably took off for second. O’Farrell gunned a perfect strike to second. Hornsby tagged out the sliding Ruth. The slugger had lost his bet and the Cardinals had won their first world championship.1

Sources

Doutrich, Paul E., The Cardinals and the Yankees, 1926: A Classic Season and St. Louis in Seven (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2011).

Notes

1 After the game Ruth explained that he took off on his own. He figured that as well as Alexander was pitching he wanted to be in scoring position in case Meusel got a hit. It is the only time a World Series has ended with a runner caught stealing.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Cardinals 3

New York Yankees 2

Game 7, WS

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.