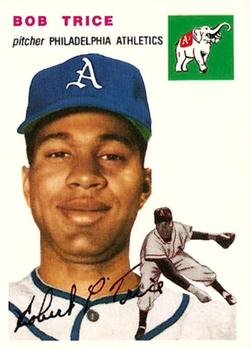

September 13, 1953: Bob Trice becomes first Black player on Philadelphia A’s

“Bob Trice has richly earned this reward,” proclaimed Ottawa Athletics manager Frank Skaff, in response to Trice’s September 1953 call-up by Philadelphia’s American League club.1 There was no doubt that Trice’s promotion was warranted. The 27-year-old right-hander had successfully made the jump from the Class C (Québec) Provincial League to the International League that season, and he more than held his own at Triple A. He posted a 21-10 record, was named to the International League All-Star team, and won both the Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Pitcher Awards.

“Bob Trice has richly earned this reward,” proclaimed Ottawa Athletics manager Frank Skaff, in response to Trice’s September 1953 call-up by Philadelphia’s American League club.1 There was no doubt that Trice’s promotion was warranted. The 27-year-old right-hander had successfully made the jump from the Class C (Québec) Provincial League to the International League that season, and he more than held his own at Triple A. He posted a 21-10 record, was named to the International League All-Star team, and won both the Rookie of the Year and Most Valuable Pitcher Awards.

Trice had been a fan favorite in Canada’s capital. On top of his mound achievements, the Georgia native swung a potent bat, slamming four home runs and getting regular at-bats as a pinch-hitter.2 He was celebrated by the fans on August 13 when the team hosted Bob Trice Night, which was an emotional affair. “The fans were nice enough to give me a night and I can’t forget the thrill when my mother was brought here for that party,” he said.3

The excited hurler was grateful for the supportive environment in the Ottawa clubhouse, and he let everyone know how he felt before he left town. “Frank Skaff treated me well … and all the boys helped me plenty too,” Trice explained.4

He was told to be ready to pitch on September 13 against the St. Louis Browns, so he made the long drive from Ottawa to Pittsburgh, said a quick hello to his mother, and hopped on a train to the City of Brotherly Love.5

The reception from Trice’s new teammates on the day he arrived contrasted sharply with his Triple-A experience, as the rookie hurler was initially given the cold shoulder.6 Trice put his Philadelphia uniform on for the first time in solitude before going out onto the field to get a closer look at Connie Mack Stadium. Eventually, veteran pitcher Bobby Shantz came out, introduced himself to Trice, and let him know he was glad to have him on the team. “I just went out and talked to him a little,” Shantz said. “These other guys were trying to act indifferent. I didn’t want it to bother him.”7

Philadelphia manager Jimmy Dykes gave Trice some good advice before his debut. “I don’t want you to think everything depends on this game,” Dykes told him. “You’re set to go to spring training with us next year, and this is just another game.”8

Although Trice was making his American League debut, it wasn’t his first appearance in what was eventually recognized as a major league. In 1948 he had played for the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League, one of the Black baseball leagues that in 2020 Major League Baseball acknowledged had major-league status.9 One of Trice’s mentors on the Grays was Sam Bankhead, who also managed Trice in 1951 on the Farnham (Québec) Pirates in the Provincial League.10

Future Hall of Famer Satchel Paige was another one of his mentors. “We barnstormed together in 1949, and he told me a dozen or more tricks about pitching,” Trice recalled.11 Amazingly, the ageless Paige was in uniform for Trice’s American League debut.12 The 46-year-old hurler was the Browns’ top reliever in 1953, and he was one of their two representatives at the All-Star Game.13

Rookie hurler Don Larsen (5-11, 4.33 ERA) got the start for St. Louis in the first game of the September 13 doubleheader. The 24-year-old right-hander was on a roll, having won his previous three starts.14

The Browns, limping toward the end of their final season in St. Louis, were dead last in the American League standings. They trailed the seventh-place Athletics by only 3½ games, thanks to Philadelphia’s 16 losses in its previous 18 contests.

The 8,477 fans in attendance – a big crowd for the Athletics in 1953 – watched Trice retire the Browns in order in the top of the first inning.15

Vic Wertz opened the second inning by slamming Trice’s first pitch off the center-field light standard for a triple.16 The next batter, Vern “Junior” Stephens, singled him home. The Browns added another run on a fielder’s choice, an infield single, and Bobby Young’s sacrifice fly.

After Larsen cruised through the first two innings, Athletics shortstop Joe DeMaestri opened the bottom of the third by homering to left field, cutting the Browns’ lead to 2-1.

St. Louis got that run back quickly when Stephens homered off Trice with one out in the fourth. Trice bounced back by retiring the next 10 batters he faced. The streak was broken when Les Moss singled and was thrown out trying to stretch it into a double. In the bottom of the inning, Philadelphia cut the lead to 3-2 on an RBI groundout by second baseman Cass Michaels.

Larsen helped his own cause by smacking his third homer of the season with one out in the top of the eighth. The next batter, Billy Hunter, sliced an opposite-field double,17 and he scored when Dick Kryhoski doubled off the wall, giving the Browns a 5-2 lead. Trice got out of the inning without allowing any further damage, and he was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the inning.

Larsen limited Philadelphia to four hits through eight innings before running out of gas in the ninth. A walk to Dave Philley and a single by Elmer Valo brought the tying run to the plate with only one out, so Browns manager Marty Marion brought in veteran reliever Marlin Stuart. He quickly snuffed out the Philadelphia rally, giving the Browns their 51st win against 93 defeats.

Trice showed flashes of brilliance in his debut, as he recorded five one-two-three innings and didn’t walk a single batter.18 Some believed that he may have thrown too many strikes. Art Morrow of the Philadelphia Inquirer felt that Trice’s “penchant for grooving first pitches proved costly.”19 Wertz (triple), Stephens (single, homer), Larsen (homer), and Kryhoski (double) all reached base safely on the first pitch of an at-bat and all were key hits.20

Trice made history by becoming the first Black player on a Philadelphia team in the American or National League.21 Almost 6½ years after Jackie Robinson had broken the color barrier, the Athletics became the seventh of 16 major-league teams to integrate.22 Four days later, 22-year-old Ernie Banks became the first Black player on the Chicago Cubs, but it was almost six more years before all 16 teams were finally integrated.23

Despite pitching poorly in his next start, Trice picked up his first American League win in a 13-9 victory over the Washington Senators. He was much better in his third and final start, a complete-game victory over those same Senators. Trice finished the season with a 2-1 record and a 5.48 ERA.

The Athletics, well aware of the additional challenges facing Black players, hired future Hall of Famer Judy Johnson as a spring-training coach in 1954 to help Trice and Vic Power with the transition.24 Johnson was responsible for providing guidance to the pair both on and off the field.

After making the team out of spring training, Trice tossed complete-game victories in his first four regular-season starts. With a 4-0 record and a 1.75 ERA in early May, Trice seemed poised for a run at the American League Rookie of the Year Award.

And then suddenly, it all fell apart. Between May 9 and July 11, Trice went 3-8 with a 7.27 ERA. Since Johnson wasn’t retained as a coach for the regular season,25 Trice was left without “a willing mentor and companion” who could help him deal with adversity.26 After getting bombed by the Boston Red Sox in an 18-0 rout on the final day before the All-Star break, he shocked his manager and teammates by requesting a demotion to Ottawa.27 Part of their surprise stemmed from the fact that the dejected hurler was still leading the lowly Athletics with seven wins.28 Trice explained that playing in the major leagues wasn’t fun anymore. “Maybe I am crazy, as everyone says, but to me the reasons seem logical enough,” he concluded.29

The details behind Trice’s unhappiness in the big leagues weren’t widely known until decades later. Not surprisingly, many of the underlying issues were race-related. For instance, he was upset with the Athletics organization for not properly addressing the incidents of racial intolerance that he faced while traveling with the team in the South. In one humiliating incident, Trice was refused entry into a restaurant, and he had to wait on the team bus while his White teammates ate their meals.30

Years later, he told his son, Bob Trice Jr., that “dealing with race took precedence over the game.”31 Given that Triple-A salaries weren’t significantly different from those paid to major-league rookies,32 requesting a return to Ottawa was perfectly “logical.”

Trice pitched well enough in Ottawa in 1954 to earn another September call-up, although he never saw any game action with Philadelphia.33

The Athletics moved to Kansas City for the 1955 season, and Trice started the season with the big club. After four relief appearances in which he gave up 10 earned runs in 10 innings, he was sent down to Triple A. Trice never played in the big leagues again.

Epilogue

The 16 American and National League teams were gradually integrated between 1947 and 1959. Bob Trice was the only pitcher to break the color barrier on one of those teams.

Trice’s tenure with the Athletics was brief − he threw 142 innings in Philadelphia and 10 more in Kansas City.

No Black pitcher tossed 200 or more career innings for Philadelphia in the National or American League until Grant Jackson exceeded that threshold in 1969. Jackson, who made his Phillies debut in 1965, would have surpassed 200 innings sooner had the Phillies not acquired two veteran pitchers, 34-year-old Larry Jackson and 37-year-old Bob Buhl, in a trade with the Chicago Cubs on April 21, 1966.34 (Jackson spent most of 1966 in the Pacific Coast League.) One of the players given up by the Phillies in that trade was future Hall of Famer Fergie Jenkins.35

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kurt Blumenau and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, the Negro Leagues Database at Seamheads.com, and The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHA/PHA195309131.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1953/B09131PHA1953.htm

Notes

1 “Ottawa’s Bob Trice Sold Outright to ‘Big A’s,’” Ottawa Citizen, September 8, 1953: 1.

2 Art Morrow, “A’s Buy Trice; First Negro to Join Phila. Club,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 9, 1953: 49.

3 Jack Koffman, “Along Sport Row,” Ottawa Citizen, September 9, 1953: 18.

4 Bill Westwick, “The Sport Realm,” Ottawa Journal, September 9, 1953: 16.

5 Westwick.

6 Ron Thomas, “A’s First Black Player Is Subject of Tribute,” Marin Independent Journal (San Rafael, California), February 7, 1997: C-1.

7 Thomas.

8 Art Morrow, “A’s Get Peek at Pair of ’53 Farm Prizes,” The Sporting News, September 23, 1953: 6.

9 In December 2020, Major League Baseball acknowledged that seven Black baseball leagues were major leagues, including the Negro National League II (1933-1948).

10 Bankhead became the first Black manager of a mainly White professional baseball team in 1951. Jack Morris, “Bob Trice,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bob-trice/, accessed December 29, 2021. Dave Wilkie, “Sam Bankhead,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/sam-bankhead/, accessed December 29, 2021.

11 Koffman.

12 Paige had made his major-league debut in 1927 with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro National League I. Based on his commonly accepted birthdate of July 7, 1906, he was 42 years old when he played his first game in the American or National League as a member of the 1948 Cleveland Indians.

13 Billy Hunter was the Browns’ other All-Star. Paige made only two more appearances in a St. Louis Browns uniform after Trice’s Philadelphia debut. Although Paige finished the 1953 season with an ERA+ of 119 (which meant his park-adjusted ERA was 19 percent better than league average), Paige chose to retire instead of following the Browns to Baltimore in 1954. Among other reasons, Paige stated that he had been treated poorly in previous visits to Baltimore. Kurt Blumenau, “September 22, 1953: Satchel Paige, Don Larsen lead St. Louis Browns to their final win,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/september-22-1953-satchel-paige-don-larsen-lead-st-louis-browns-to-their-final-win, accessed December 23, 2021; “With Veeck, His ‘Sponsor,’ Gone, Ol’ Satch May Retire,” The Sporting News, November 18, 1953: 26.

14 Larsen had been mired in a slump in the middle of August with a 2-11 record and 4.78 ERA. His season turned around immediately after he pitched in an August 20 exhibition game in Baltimore against the Triple-A Orioles. Larsen tossed a five-hit, complete-game victory, striking out 11 batters. A curious 10,681 fans were in attendance, many hoping that the Browns would eventually move to Baltimore. Shortly after the 1953 season, owner Bill Veeck sold the team and it was moved there. “10,681 Baltimore Fans Whoop It Up for the Browns in 8-2 Win,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 21, 1953: 1C.

15 Only 1,015 fans had come out to Connie Mack Stadium to see a very good Chicago White Sox ballclub the previous day (on a Saturday afternoon). Attendance at Philadelphia Athletics games fell from 627,100 in 1952 to 362,113 in 1953 – an average of 4,642 per game.

16 Art Morrow, “A’s, Browns Divide; Byrd Takes 2d, 2-0,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 14, 1953: 29.

17 Morrow, “A’s, Browns Divide; Byrd Takes 2d, 2-0.”

18 Trice had five one-two-three innings if one considers the top of the seventh to be a one-two-three inning. He faced only three batters, but Les Moss singled and was thrown out trying to stretch it into a double. Moss was the third out of the inning.

19 Morrow, “A’s, Browns Divide; Byrd Takes 2d, 2-0.”

20 Morrow, “A’s Get Peek at Pair of ’53 Farm Prizes.”

21 The Philadelphia Phillies were the last National League team (14th overall) to integrate. John Kennedy became the first Black player on the Phillies when he appeared as a pinch-runner on April 22, 1957 – more than 4½ years after Trice’s Philadelphia debut.

22 Depending on one’s point of view, the Philadelphia Athletics were either the seventh or eighth big-league team to integrate. Some believe the Pittsburgh Pirates were the seventh, since Carlos Bernier (born in Juana Diaz, Puerto Rico) debuted for the Pirates on April 22, 1953. Others believe that Curt Roberts (born in Pineland, Texas) was the first Black player on the Pirates. He debuted with the team on April 13, 1954.

23 The Boston Red Sox were the last team to integrate when Pumpsie Green made his major-league debut on July 21, 1959.

24 Power had been acquired in a trade with the Yankees in December 1953. Art Morrow, “A’s Ink First Negro Coach in Big Time,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1954: 18.

25 Lloyd H. Barrow, Team First: History of Baseball Integration & Civil Rights (New York: Page Publishing, 2018).

26 Bill Madden, 1954: The Year Willie Mays and the First Generation of Black Superstars Changed Major League Baseball Forever (Boston: Da Capo Press, 2014), 4.

27 Art Morrow, “Bob Trice Requests Return to Minors to ‘Have Fun Pitching,’” The Sporting News, July 21, 1954: 31.

28 Trice did not throw a single pitch for Philadelphia in the second half of the 1954 season, yet he still finished second on the team with seven wins.

29 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1994), 103.

30 After Trice’s teammates finished their meals, they brought him three hot dogs in a doggie bag. He declined to eat the hot dogs. Thomas.

31 Thomas.

32 Thomas.

33 Art Morrow, “A’s Recall Five from Farm Club,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 14, 1954: 29.

34 Maxwell Kates, “Grant Jackson,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/grant-jackson/, accessed December 29, 2021.

35 On December 16, 1970, the Phillies traded Jackson, Sam Parrilla, and Jim Hutto to the Baltimore Orioles for Roger Freed.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Browns 5

Philadelphia Athletics 2

Game 1, DH

Connie Mack Stadium

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.