September 30, 1971: Senators forfeit final home game in Washington, DC

“Well, it’s a strange way to lose a ball game,” said Ron Menchine, the Washington Senators’ play-by-play announcer, on WWDC radio.1 “It’s a strange way to wind up major league baseball in the nation’s capital … but I guess it’s been a topsy-turvy season, no one believed that there would not be major league baseball in the nation’s capital. But it’s sad to report there no longer is.”

For the second time in 12 years, a Washington baseball team prepared to leave. This time, the major league powers that were wouldn’t replace it with a new team, under the same name or otherwise. The ancient, not-always-accurate legend “Washington: First in war, first in peace, and last in the American League,” changed the final phrase to “gone.”

On the last day of the 1971 regular season, a likely 7-5 Senators win became a forfeit to the New York Yankees. Heartsick fans poured onto and destroyed the field before Senators reliever Joe Grzenda could pitch to Yankees second baseman Horace Clarke with two out and nobody on in the top of the ninth. “It’s a shame,” Menchine said on the air, “that they couldn’t have waited for one more out.”

We’ll never know if Menchine intended to approve the RFK Stadium crowd rioting for souvenirs of Washington baseball if and when Grzenda got Clarke out to finish the game. We do know that the final day of Senators baseball gave the fans exactly one thing they wanted, after behemoth first baseman Frank Howard checked in at the plate to open the bottom of the sixth.

The Yankees were still in the middle of their lost decade of 1965-75. On that Thursday night, though, they gave starting pitcher Mike Kekich a 5-1 lead. They did it with flashes of their once-vaunted power — home runs by Rusty Torres (solo, top of the first), Bobby Murcer (a two-run shot, top of the second), and Roy White (solo, top of the fifth) — plus an RBI single (John Ellis, top of the first), all off Senators starter Dick Bosman.2

The Senators scored their only run of the first five innings when Yankees shortstop Frank Baker misplayed Senators second baseman Tom Ragland’s grounder, enabling third baseman Dave Nelson to score with one out in the bottom of the second. Kekich took a four-hitter into the sixth when Howard stood in against him leading off.

A former Dodger who found a home and built a love affair with Washington fans, the gentle giant wanted nothing more than to give them one more home run to remember. He got what he wanted on 2-and-1, driving one off the bullpen’s back wall to a thunderous ovation. “I just wish the owners of the American League could see this, the ones who voted 10 to 2 to move this club out of Washington,” Menchine said as Howard crossed the plate, before describing what happened next:

He comes out again. … Hondo threw his helmet into the stands, a souvenir of the big guy’s finest hour in Washington. … The crowd screaming for Howard to come out again … and here he comes again!! … A tremendous display of the enthusiasm of Washington fans for Frank Howard. … Hondo loves Washington as much as the fans love him. It’s 5-2 …3

A week earlier, Shirley Povich, the grand old man of Washington sportswriting, summed up the self-imposed dilemma of Senators owner Bob Short that cost the city major-league baseball at last:

They paid scant heed to the fact that Short foolishly overborrowed to buy the team and then pleaded poverty, and to the stubborn refusal of this novice club owner to hire a general manager, and his record of wrecking the club with absurd deals. … [T]he impoverished Senators were the only team in the league billed for the owner’s private jet, with co-pilots. The owners had ears only for his complaint that he couldn’t operate profitably in Washington.

They showed utterly no concern for the Washington fans, who were asked to support last-place teams by paying the highest prices in the league, a little matter Short arranged by trading away his infield and boosting the ticket prices far beyond those of the Baltimore Orioles, who were playing the best baseball in the league only forty miles away.4

Historian Tom Deveaux couldn’t resist observing that, among the banners hoisted in or hung from the stands, were enough displaying Short’s initials.5

When Short seemed at last to find a buyer willing to keep the team in Washington, it was World Airways chief Ed Daly, offering a $9 million price. (Short first sought $12.4 million.) Oakland Athletics owner Charlie Finley abstained in the first vote on the Senators move, but demanded that Daly decide quickly to buy the team. When Daly pleaded that he couldn’t decide “that fast,” Finley changed his vote to yes, as did California Angels owner Gene Autry through a proxy. (Autry was in a New England hospital for surgery.)6

Howard’s blast didn’t just drive the fans mad, it kicked the Senators lineup awake. The continuing commotion from there may have knocked the Yankees a little further off their own game, too: They committed three of their five errors between the sixth and the eighth.

Catcher Rich Billings and left fielder Jeff Burroughs followed Howard with back-to-back singles, chasing Kekich from the game in favor of Jack Aker. Nelson bunted up the first-base line and beat Aker’s throw to first, but the offline throw past Ellis at first allowed Billings to score and Burroughs to take third.

Senators right fielder Del Unser grounded back to the box, and Burroughs scored as Aker made his only available play, to first. Aker struck out Ragland, put pinch-hitter Don Mincher aboard with an intentional walk, and surrendered a game-tying RBI double to Elliott Maddox that turned into a side-retiring out when Mincher was thrown out trying to score behind Nelson.

Paul Lindblad pitched two shutout innings for the Senators in the seventh and the eighth. Fans began jumping onto and off the field in the top of the eighth. Lindblad’s pinch-hitter Tom McCraw singled Nelson home with one of two unearned runs in the bottom of the inning after a pair of Yankee infield fielding errors. Maddox sent Ragland home with the second on a sacrifice fly.

All Grzenda had to do was get rid of the Yankees in the top of the ninth. Easier said than done. Grzenda got back-to-back groundouts right back to himself, from pinch-hitter Felipe Alou and Murcer. Then players left the field as fans began pouring onto it. “[O]ne young rebel from the stands set off again,” Povich would write for the following morning:

He grabbed first base and ran off with it. Some unbelievers, undaunted by the warning of forfeit, cheered, and from out of the stands poured hundreds, maybe a couple of thousand fans. They took over the infield, the outfield, grabbed off every base as a souvenir, tried to get the numbers and lights from the scoreboard or anything else removable, and by their numbers left police and the four umpires helpless to intervene.7

“This will not be a complete game unless they get back. This will not be a complete game unless they get back,” Menchine told his listeners, repeating himself deliberately and with melancholy aforethought.

So we certainly hope that this ballgame can be concluded. The players now are clearing the field. … as pandemonium has broken loose … and the field is filled with many souvenir hunters. … The Senators lead, 7 to 5, with two outs. … Police are trying to restore order, but the crowd continues to mill all around the field. … Some fans are scooping up dirt … more and more now are converging on the field. …

Menchine finally gave the word: The game was forfeited to the Yankees. “They could just never get the crowd under control at all, they just kinda stood out on the field and milled around,” Billings remembered many years later. “We all went in the clubhouse just to wait and see what happened, and I don’t know if I ever even came back out.”8

Grzenda managed to keep the ball he never got to pitch to Clarke. It didn’t sail up to the plate until Opening Day 2005, when a subsequent round of shenanigans brought “The Show” back to Washington, turning the Montreal Expos into the Washington Nationals. Grzenda brought the ball to RFK Stadium but handed it instead to President George W. Bush. The president wore a new Nationals team jacket as he fired a strike to catcher Brian Schneider.

Major-league baseball took the same number of years to return to Washington as the number on Frank Howard’s back: 33.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/WS2/WS2197109300.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1971/B09300WS21971.htm

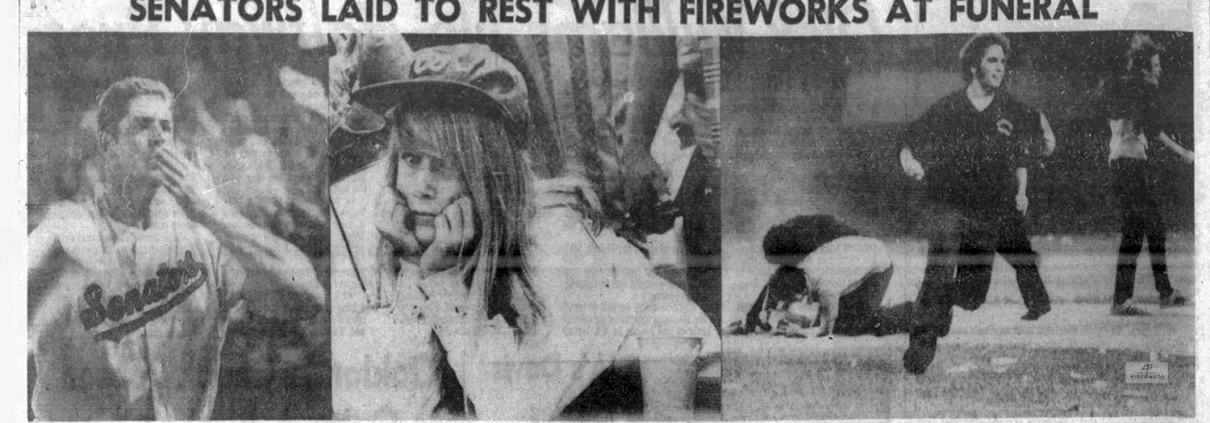

Photos from Baltimore Sun, October 1, 1971, via Newspapers.com.

Notes

1 “1971 09 30 Senators Final Game Washington vs Yankees Forfeit Game Broadcast,” YouTube, youtu.be/083g2tqVE78, accessed December 7, 2020.

2 Torres became part of two subsequent infamous 1970s fan riot forfeits: Ten Cent Beer Night in Cleveland, in 1974, when he was a member of the Indians and the game was forfeited to the Texas Rangers — the erstwhile Senators; and Disco Demolition Night in Chicago, 1979, when he was a member of the White Sox.

3 “1971 09 30 Senators Final Game Washington vs Yankees Forfeit Game Broadcast.”

4 Shirley Povich, “The Senators Leave — Again,” Washington Post, September 23, 1971; republished in Povich, All Those Mornings … at the Post, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Books Group, 2005).

5 Tom Deveaux, The Washington Senators 1901-1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001).

6 Deveaux.

7 Povich, “The Senators’ Final Game,” Washington Post, October 1, 1971; republished as “The Last Waltz” in Povich, All Those Mornings … at the Post.

8 Chris Jones, “Rich Billings,” SABR BioProject, sabr.org/bioproj/person/rich-billings/, accessed December 7, 2020.

Additional Stats

Washington Senators 7

New York Yankees 5

Game forfeited to Yankees in 9th inning

RFK Stadium

Washington, DC

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.