September 7, 1952: Hartford goes out a winner before 64-year break from Organized Baseball

Hartford, Connecticut, is among the baseball markets that has found new life in the flashy, merchandise- and promotion-driven minor-league climate of the twenty-first century. Since 2016 the city has hosted the Hartford Yard Goats, a Colorado Rockies affiliate in the Double-A Eastern League.1 The Yard Goats touch all the bases of modern minor-league ball — a goofy animal mascot, a nickname with a tenuous link to local history,2 and familiar ballpark promotions ranging from local food specialties to the television show The Office.3

city has hosted the Hartford Yard Goats, a Colorado Rockies affiliate in the Double-A Eastern League.1 The Yard Goats touch all the bases of modern minor-league ball — a goofy animal mascot, a nickname with a tenuous link to local history,2 and familiar ballpark promotions ranging from local food specialties to the television show The Office.3

Before the Yard Goats’ arrival, you have to go back to 1952 to find minor-league ball in Connecticut’s capital. That was the final year that two major-league teams called New England home. The Hartford Chiefs of the Class A Eastern League were affiliated with the less successful of those teams, the Boston Braves, as they had been for 15 years under various names.4

Under the leadership of New England native and former Braves manager Del Bissonette, Hartford went 59-79 in 1952 and finished seventh in the eight-team league, 24 games behind the Albany (New York) Senators.5 They played home games at Bulkeley Stadium, a facility named for Morgan Bulkeley, Baseball Hall of Famer, former National League president, US senator, Connecticut governor, Hartford mayor.6

A crowd of 461 showed up on September 7, 1952, for the doubleheader that concluded the Chiefs’ season. Six members of that year’s team appeared in the big leagues, but only one — third baseman Ted Sepkowski — played in the final game.7 There might have been more but for injuries. Catcher Bob Roselli wrenched a knee in the first game of the doubleheader, was carried off the field, and could not appear in the nightcap.8 Another future big leaguer, infielder Joe Morgan, was injured more dramatically in an August 29 auto accident involving four Chiefs players in Killingly, Connecticut. Teammate Charlie Bicknell pulled the unconscious Morgan out of an overturned and burning car after it collided with a truck. The future Red Sox manager’s life was saved, but injuries from the accident sidelined him for the rest of the season.9

Hartford’s opponent on September 7 was the Schenectady (New York) Blue Jays, a Philadelphia Phillies affiliate and the league’s fourth-place team. The Blue Jays closed the year 10 games back with a 73-65 record under the direction of player-manager Danny Carnevale. A longtime minor-league infielder, manager and scout, Carnevale later served as a coach for the 1970 Kansas City Royals in his only big-league season.

Seven members of the Blue Jays reached the major leagues, and the best-known was probably the second game’s starting pitcher — future National League Rookie of the Year Jack Sanford, who went 16-8 with a 2.94 ERA in 1952. Others in the starting lineup who made “The Show” included left fielder Jim Command and first baseman Stan Hollmig.10

After Hartford’s 4-3 win in the first game, Sanford faced off against Chiefs starting pitcher Don Schmidt, a 27-year-old righty who had attended Seton Hall University. Between the Class A and Triple-A levels, Schmidt compiled an 8-13 record and 4.13 ERA in 1952, his sixth and last season in Organized Baseball.

Hartford grabbed a quick lead in the first inning off Sanford, who, reports noted, “didn’t have his usual sharpness.”11 Center fielder Vince Pizzitola worked a walk and Sepkowski drove him in with a double. Second baseman Eddie McHugh followed with another walk, and right fielder Jimmy Francoline singled in Sepkowski to make it 2-0.12 The two first-inning walks marked the start of an afternoon’s struggle for Sanford, whose complete game included seven free passes, one hit batter, and only three strikeouts.

Francoline, incidentally, was a Hartford native and veteran of 15 years of minor-league ball. He had retired after the 1951 season but signed with the Chiefs to fill out their roster after the August 29 car accident. His seven games in 1952 were the last of his professional career.13

Hartford tacked on another run in the fourth after pitcher Schmidt doubled. First baseman Billy Smith sacrificed Schmidt to third, and Pizzitola brought him home with a fly out.14 Despite hitting only .215 for the year, Pizzitola played a part in two of the Chiefs’ three tallies.

Schmidt was more effective than Sanford, limiting the Blue Jays to no more than one hit in any inning. He also worked a complete game, yielding six hits and only one walk against three strikeouts. Schenectady’s only rally came in the ninth inning, when third baseman Walter Derucki led off with a homer to make the score 3-1. With two out, a pair of home-team errors put the tying runs on base.15 Hollmig, a .290 hitter that year, lined out to Sepkowski at third to end the game and the season.16

The Chiefs struggled at the gate, drawing only 36,000 fans, an average of about 520 per home game. In November the management of the parent Braves put their money-losing affiliate up for sale for a token $1, stating that they would return to Hartford “under no considerations whatsoever.” The Sporting News characterized the Chiefs as a “TV casualty,” unable to compete against television broadcasts from five nearby major-league teams.17

Of course, one of those five nearby major-league teams was gone by the start of the 1953 season. The Braves moved from Boston to Milwaukee, replacing the Hartford team with two Class A affiliates in Lincoln, Nebraska, and Jacksonville, Florida. Nineteen-year-old Hank Aaron hit .362 for the 1953 Jacksonville club. Perhaps if more Connecticut residents had supported the ’52 Chiefs, they would have seen baseball’s eventual home-run leader in a Hartford uniform the following year.

Bulkeley Stadium sat mostly unused until its demolition in the summer of 1960. A small fire was reported at the ballpark shortly before it was razed; news accounts indicated that former Boston Braves owner Lou Perini still owned the property.18 Famous players who appeared there, either as minor leaguers or in exhibition games, included Josh Gibson, Lou Gehrig, Satchel Paige, Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Warren Spahn, Roy Campanella, and Jim Thorpe.19 Its former location at Hanmer and George Streets in the city’s South End is now occupied by a nursing home, with a marker honoring the ballpark at its entrance. The Yard Goats play elsewhere in the city, in a new stadium known — in keeping with twenty-first-century sponsorship norms — as Dunkin’ Donuts Park.

Sources

In addition to the specific sources cited in the Notes, the author used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for general player, team and season data.

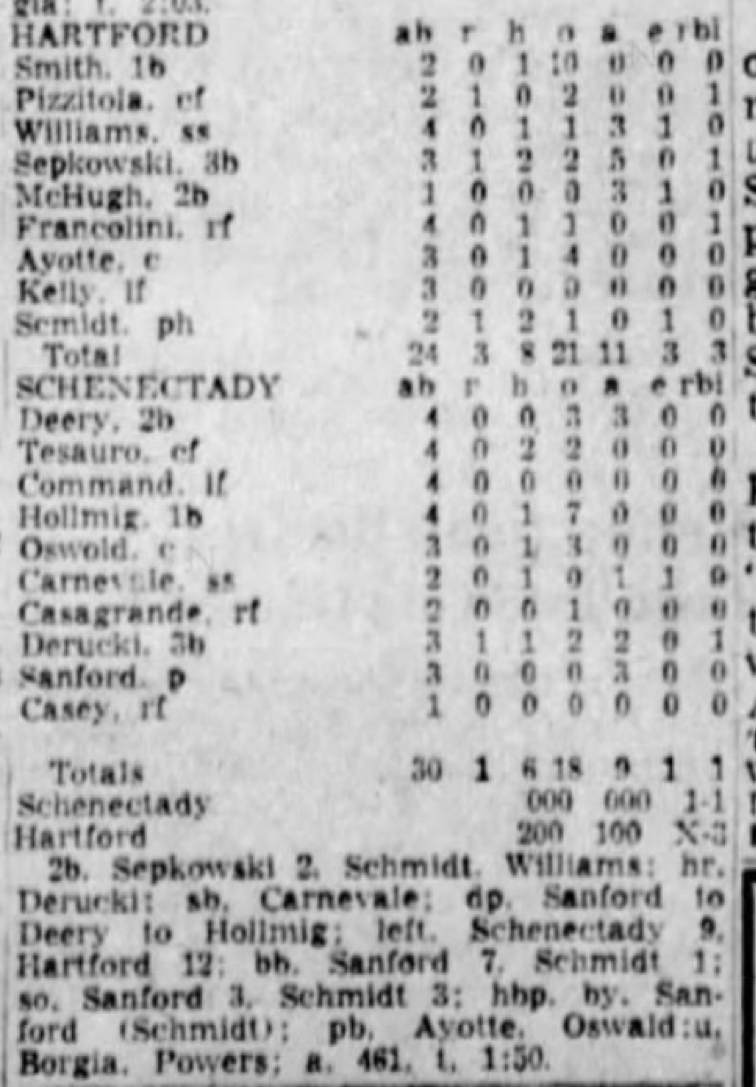

Neither Baseball-Reference nor Retrosheet provides box scores of minor-league games, but the September 8, 1952, editions of the Hartford Courant and Schenectady Gazette published box scores for this game. The box score shown below is taken from the Hartford paper.

Notes

1 Technically, Hartford has hosted the Yard Goats since 2017. The team started play in 2016, but played its first year of home games on the road because construction of its ballpark was delayed. This story uses 2016 for the franchise’s first year in Hartford, even though the team did not play there that season.

2 A yard goat is a small locomotive used in railroad yard switching. The Yard Goats’ ballpark was built on a former railroad yard, and the club’s branding mimics the typeface once used by the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad. More information on the name is in Garry Brown, “Ever Wonder Where Hartford Yard Goats Name Comes From? Here’s the Story,” MassLive.com, May 3, 2019. Accessed online October 23, 2020.

3 Promotions from the Yard Goats’ unplayed 2020 schedule, accessed online October 23, 2020.

4 Before taking the name Chiefs, the team was also known as the Bees and the Laurels.

5 Despite their name, the Albany Senators were a Boston Red Sox farm club, according to Baseball-Reference.

6 The ballpark opened in 1921 as Clarkin Field and was renamed for Bulkeley in 1928.

7 Other major-leaguers who played for the 1952 Chiefs but are not mentioned in this piece include Ray Crone and Jim Frey. Crone started and won the first game of the September 7 doubleheader.

8 Ronald Melcher, “Chiefs Close Season with Pair of Wins,” Hartford Courant, September 8, 1952: 12.

9 Associated Press, “4 Hartford Ball Players Hurt in Flaming Crash,” Hartford Courant, August 30, 1952: 1.

10 Other members of the Blue Jays who reached the majors included Ted Kazanski, Thornton Kipper, Ron Mrozinski, and Gene Snyder.

11 Associated Press, “Jays Defeated Twice by Chiefs,” Schenectady (New York) Gazette, September 8, 1952: 14.

12 “Jays Defeated Twice by Chiefs.”

13 Dennis J. Riley, “Bicknell Saves Two Teammates from Fiery Car,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1952: 37. News accounts from 1952 spell the name Francolini and credit him with 17 years in the minors. Baseball-Reference spells it Francoline and credits him with 15. The latter discrepancy may have something to do with Francoline’s apparent absence from Organized Baseball in 1940, 1942, and 1949. An obituary on page B7 of the June 10, 2012, Hartford Courant identifies him as James J. Francoline Sr.

14 “Jays Defeated Twice by Chiefs.”

15 News accounts do not specify which players made the errors. Hartford committed three in the game — one apiece by pitcher Schmidt, second baseman McHugh, and shortstop Leonard Williams.

16 Melcher.

17 Roger Birtwell, “Braves Give Up Hartford, TV Casualty,” The Sporting News, November 19, 1952: 17.

18 “Record of Fires, Mon., June 6, 1960,” Hartford Courant, June 7, 1960: 23.

19 Bill Lee, “With Malice Toward None,” Hartford Courant, July 7, 1960: 25.

Additional Stats

Hartford Chiefs 3

Schenectady Blue Jays 1

Game 2, DH

Bulkeley Stadium

Hartford, CT

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.