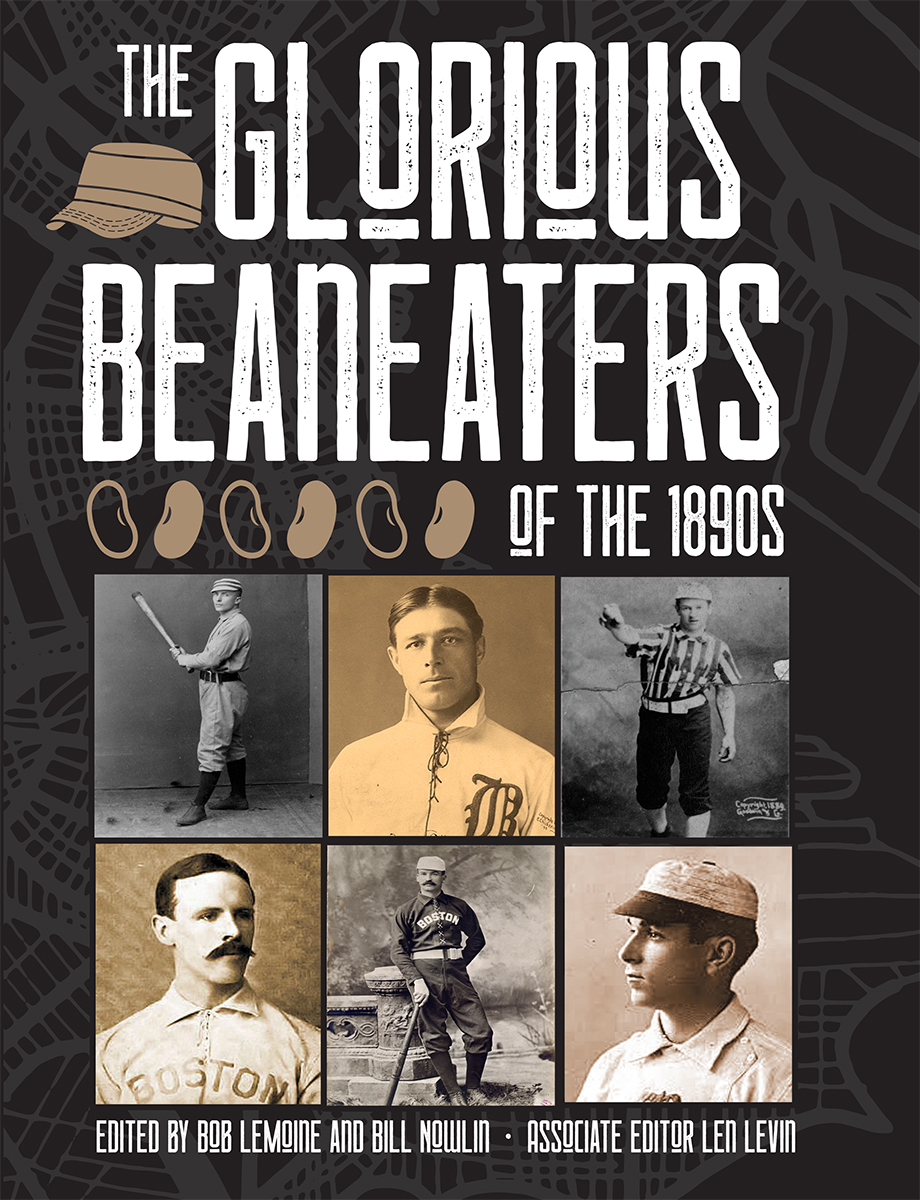

1895 Boston Beaneaters: Strictly for the Birds, Again

This article was written by Bob LeMoine

This article was published in 1890s Boston Beaneaters essays

The Boston Beaneaters were coming off a disappointing third-place finish in 1894 at 78-54. If that doesn’t sound disappointing, take into account that the team had won three straight National League pennants (1891-1893) and set the bar and the expectations of Boston fans high. In 1894 the Beaneaters didn’t have a losing month or even a losing streak of over three games, but simply were outplayed by both New York and pennant winner Baltimore. After beating Baltimore on July 30, Frank Selee’s Beaneaters led the Orioles and New York Giants by five games. While finishing a strong 29-22, Boston was no match for Ned Hanlon’s Baltimore team, which went 43-10 from that point on and the Giants, who were 40-13. Baltimore won 18 in a row from late August to mid-September and outlasted the Giants by three games. Baltimore, 60-70 in 1893 and a perennial second-division club since its days in the American Association, was now on the baseball map as it began its own dynasty.

The Boston Beaneaters were coming off a disappointing third-place finish in 1894 at 78-54. If that doesn’t sound disappointing, take into account that the team had won three straight National League pennants (1891-1893) and set the bar and the expectations of Boston fans high. In 1894 the Beaneaters didn’t have a losing month or even a losing streak of over three games, but simply were outplayed by both New York and pennant winner Baltimore. After beating Baltimore on July 30, Frank Selee’s Beaneaters led the Orioles and New York Giants by five games. While finishing a strong 29-22, Boston was no match for Ned Hanlon’s Baltimore team, which went 43-10 from that point on and the Giants, who were 40-13. Baltimore won 18 in a row from late August to mid-September and outlasted the Giants by three games. Baltimore, 60-70 in 1893 and a perennial second-division club since its days in the American Association, was now on the baseball map as it began its own dynasty.

Boston made very few acquisitions during the offseason, and the starting nine was exactly the same as in 1894. The only move of significance was the purchase of third baseman Jimmy Collins from Buffalo. The future Boston star and Hall of Famer played in only 11 games in 1895 before being farmed out to Louisville as Beaneaters veteran Billy Nash was still in charge of the hot corner.

Baltimore made no significant changes in the offseason, although the club had to rebuild the Union Grounds grandstands and clubhouses after a fire on January 14, 1895. The entire ballpark could have been gone had it not been for the groundskeeper, who lived on the grounds in a small cottage near the ticket office.1 Iron pillars were installed to support the grandstand, instead of wood.

There were more significant changes in the rules of baseball during the offseason. Baseball magnates ruled that only catcher’s mitts and first basemen’s gloves could be larger than 14 inches in circumference or weigh over 10 ounces. Tim Murnane of the Boston Globe was opposed to any “big glove rule,” calling the mitt “a detriment to the sport.” He asserted that all but two magnates agreed with him, and the two, Al Spalding and Al Reach, were in the sporting-goods business. The size of the rubber on the pitcher’s mound was doubled to 24 by 6 inches. The infield-fly rule was put into place, and a held foul tip was ruled to be a strike. Players were also not allowed to coach first or third base after being replaced during the game.2 Murnane reported that 20 men on the Boston payroll traveled to Charlestown, South Carolina, for spring training. Perhaps they discussed the rule changes on the train ride down, or maybe the authority given to umpires to levy heavier fines for player rowdiness.

Twenty-five spring exhibition games were planned from March 20 to April 18, the last six of them in the Northeast.3The Beaneaters returned home for Opening Day on Patriots Day, April 19. Many events were going on throughout the city, including a commemoration at Old North Church of Paul Revere’s ride. At 2:30 P.M., Boston took on Washington at the South End Grounds.4 Boston fell behind 4-1, but poured on seven runs in the seventh, including a bases-loaded double by Tommy McCarthy, leading to an 11-6 win. Boston took two out of three from Washington, then lost two of three at New York, as Zeke Wilson, one of the Beaneaters’ new starting pitchers, was hammered for nine runs in three innings.5 Zeke and his 5.20 ERA didn’t last beyond June.

Baltimore opened its rebuilt park to a crowd of 15,000, which saw the 1894 pennant raised to the flagpole. But the Orioles got a taste of their own rowdy medicine as the Phillies staged a comeback in the ninth after being down 6-2. Hughie Jennings, Baltimore third baseman, used his usual tactics in trying to block the go-ahead run from scoring on a fly out. Jack Taylor would have none of it, however, and gifted Jennings with a knuckle sandwich on the way by. The game was tied, and Philadelphia would go on to spoil the Orioles’ home opener.

Boston hung around .500 for much of May, losing its fifth in a row on May 25 to close a Western road trip in a 1-0 classic as Kid Nichols was outdueled by Pittsburgh’s Pink Hawley.6 The Beaneaters were already in seventh place in the 12-team league, albeit only six games behind the first-place Pirates. But back home, Boston won 12 of its next 13, over those same Western clubs, including a 20-3 shellacking of Chicago on June 13. Jimmy Bannon, Hugh Duffy, and McCarthy each had three hits in the onslaught, and Boston now trailed Pittsburgh by a mere half-game at 24-13.7 A 15-5 domination of Philadelphia on June 26 propelled Boston to 2½ games ahead in first place, but July saw a step backward as they went 10-15 in the month. Boston was five games back as the dog days of August began.

The Beaneaters could make up ground when they traveled to Baltimore for a four-game series August 13-15 (including a doubleheader), trailing by only 4½ games. In the twin bill Boston’s pitchers were clobbered for 29 hits and 21 runs, losing 8-3 and 13-8. “Spy glass now needed to see pennant,” wrote the Globe.8 The third game was no better as they suffered a lackluster 9-2 loss. Desperately trying to salvage the final game of the series, the Beaneaters went into the 15th inning tied 10-10 with the Orioles. Baltimore’s Wee Willie Keeler reached on Bannon’s error, and scored on Hughie Jennings’s single for the 11-10 win. Boston’s season was essentially over, even if you asked Frank Selee: “Because they were the best club last year they won the pennant, and because they are the best club this year I believe they will fly the flag again. I am willing to back my opinion at even money, too.”9 By the end of August, Boston was hopelessly nine games back and far out of the pennant race.

Despite never having a lead larger than four games, Baltimore nevertheless was unstoppable in August (23-5) and September (20-7). The Orioles had to make many changes to their 1894 roster, often due to injuries. Their ace pitcher, Sadie McMahon, was plagued with arm troubles but Ned Hanlon pulled the right strings in bringing in rookie Bill Hoffer, who amazed with a 31-6 record. Second baseman Heinie Reitz also went down and one-time pitching legend Kid Gleasonfound new life in the field, where he batted .309. Boileryard Clarke filled in behind the plate and batted a solid .290 when future Hall of Famer Wilbert Robinson went down. The pitching was bolstered by Dad Clarkson, picked up in a late-season trade, and he went 12-3 down the stretch.

The surprising Cleveland Spiders were Baltimore’s biggest threat, creeping near first place in early September. With the Orioles ahead by just two games on September 7, Cleveland came to Baltimore for a three-game series. The Orioles won two out of three to increase their lead to three games. The Beaneaters themselves tried to play spoiler by beating the Orioles twice and Baltimore saw its lead slip to a half-game on September 20. But the Orioles held off the Spiders, going 7-1-1 over the final eight days. On September 28 they held a 5-2 lead over the Giants in the eighth inning. The Giants had two runners on with one out and darkness settling in. Hughie Jennings snagged a line drive from Larry Battam and doubled off George Van Haltren at second. The Baltimore Sun described the dramatic scene:

These faithful few who had been rooting until they could scarcely keep their seats from pure nervousness, whose faces had a moment before been blanched and drawn by apprehension, poured over the railing of the grand stand in a frenzy of delight, embraced and hugged any one of the Oriole players they happened to run against, and finally, laying violent hands upon the hero of the hour, the good-natured, auburn-haired shortstop, lifted him upon their shoulders and bore him across the field to the clubhouse.10

The second annual Temple Cup, by far an anticlimactic affair since, in the minds of players and fans, the tournament was a mere exhibition, began two days later. Baltimore traveled to Cleveland and lost Game One to Cy Young, prompting Cleveland fans to carry Spiders players off in their celebration. In Game Two they threw pop bottles and trash at the Orioles and set off firecrackers. The Spiders prevailed again, 7-2, behind Nig Cuppy, and then took Game Three, 7-1, with Young dominating again. Back at Baltimore in Game Four, the uninspired Orioles saw their own fans throw rotten eggs and potatoes at the Spiders, and the Orioles won, 5-0, behind Duke Esper. Cleveland players needed a police escort to leave the ballpark in one piece. Game Five saw Cleveland take the series with a 5-2 win.

Off the field, one of baseball’s classiest legends, Harry Wright, died. Wright had formed the original Cincinnati Red Stockings in 1868 and was part of Boston’s early days of professional baseball. An era had passed.

Baltimore exhibited sterling defense. Robinson (.979), first baseman Scoops Carey (.987), and Jennings (.940) had the best fielding percentages in the league at their positions. Besides Gleason (.309), the Orioles lineup boasted five others who batted .300 or better: Joe Kelley (.365), Steve Brodie (.348), Keeler (.377), John McGraw (.369), and Jennings (.386). On the basepaths, the Orioles were the masters of nineteenth-century “small ball” as their 310 stolen bases were second in the NL with five players swiping 35-plus, and their 125 sacrifices trailed only Boston. On the mound, besides Hoffer’s league-leading 31 wins and Clarkson’s unexpected 12, George Hemming won 20, and McMahon returned late to win 10.

Already known as a bunch of players who weren’t afraid to break a rule or throw a fist to win a game, the Orioles would get even more of a rugged reputation as in the offseason. They traded Gleason to the St. Louis Browns for first baseman Dirty Jack Doyle.

Boston’s club was shaken up for 1896 as well. Collins now had a spot on the roster after Nash was traded to Philadelphia for Sliding Billy Hamilton, the fastest man in the game, in the hopes that they could keep up with the swift birds. McCarthy, who spent part of 1895 injured and replaced by Fred Tenney, was sold to Brooklyn for cash. The seldom-used utilityman Frank Connaughton was sold to Kansas City of the Western League for catcher Marty Bergen.

“Clubs which have pennant-winning aspirations must depend on thorough team-work – alike in batting as in fielding and base running – for success in winning championship honors,” wrote the Spalding Guide in 1896, referring to the Orioles’ 1895 triumph.11 They indeed had all of those ingredients, and would be favored again for the pennant, while Boston tried to figure out how to stop them and build another dynasty of its own.

BOB LeMOINE was previously co-editor of Boston’s First Nine: The 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings (SABR, 2016). He has specific interests in Boston’s baseball history, the 19th Century, and the Negro Leagues, but he often jumps into any SABR project. Bob lives in New Hampshire and works as a high school librarian and adjunct professor.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Arnold, Teddie. “Union Park (Baltimore),” SABR BioProject. Retrieved May 27, 2018. https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/union-park-baltimore.

Lansche, Jerry. Glory Fades Away: The Nineteenth-Century World Series Rediscovered (Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 1991), 255-272.

Notes

1 “Fire at the Union Park Ball Grounds,” Baltimore Sun, January 15, 1895: 8.

2 T.H. Murnane, “Change in Rules,” Boston Globe, February 28, 1895: 4; David Nemec. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball (New York: Donald I. Fine, 1997), 536.

3 T.H. Murnane, “Boston’s Ball Players,” Boston Globe, March 17, 1895: 3.

4 “First Day,” Boston Globe, April 19, 1895: 12.

5 T.H. Murnane, “Wipe Out Wilson,” Boston Globe, April 27, 1895: 5.

6 “Errorless Fight,” Boston Globe, May 26, 1895: 4.

7 T.H. Murnane, “Hog Killing,” Boston Globe, June 14, 1895: 5.

8 “Hopes Dashed,” Boston Globe, August 14, 1895: 1.

9 “Selee on the Outlook,” Boston Globe, August 16, 1895: 1.

10 “The Orioles’ Pennant,” Baltimore Sun, September 30, 1895: 7.

11 Henry Chadwick, ed., Spalding’s Base Ball Guide and Official League Book for 1896 (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1996), 18.