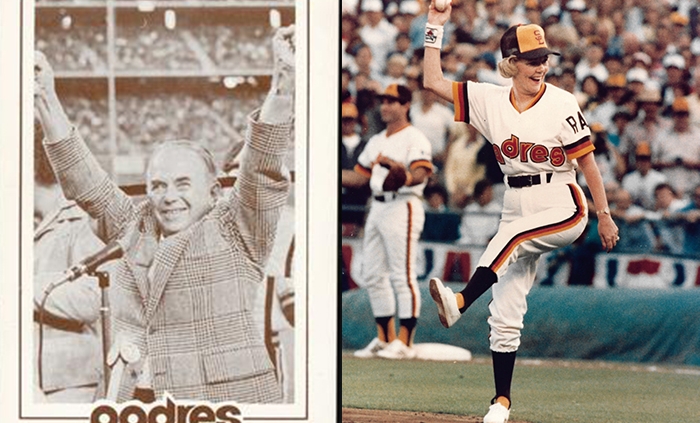

Ray and Joan Kroc

If it were not for the San Diego Padres, this biography on the lives of Ray and Joan Kroc would never have to be written. Not that the reader would be bereft of materials on this celebrated billionaire couple. Ray and Joan Kroc were both American celebrities long before they ever became associated with baseball. Hundreds of news articles from the mid-twentieth century to the early twenty-first century tell their remarkable stories of business and philanthropy. One can read Lisa Napoli’s aptly titled 2016 biography of the couple: Ray & Joan: The Man Who Made the McDonald’s Fortune and the Woman Who Gave it All Away, which brought their stories alive to a new generation. Also in 2016 was John Lee Hancock’s The Founder, a FilmNation Entertainment 2016 production starring Michael Keaton.

The story of the Krocs continues to appear on the American landscape, and for good reason. Ray Kroc’s fame came late in life when he masterfully persuaded the American public that they deserved a break today with a burger, fries, and a milkshake. The story of Ray’s third wife, Joan, the philanthropist with a political slant much different than his, is also well known. The San Diego Padres are just a small part of each of their stories.

However, this joint biography needs to be written because we cannot tell the story of the San Diego Padres without telling the stories of Ray and Joan, who owned the club from 1974 to 1990. There probably would not even be a San Diego Padres franchise today if it were not for Ray, who, with his Golden Arches worth $8 billion by the time of his death, needed a hobby in his golden years and turned to his childhood love of baseball.1 It is a story of burgers, baseball, and benevolence.

The exact origins of the hamburger are obscured in mystery, but its evolution from a beef patty served on a plate to one slapped between a bun was first displayed to the public at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. While the White Castle restaurant chain was the first trendy place to get a burger, it wasn’t until Ray Kroc revolutionized the mass production of the hamburger decades later that the concept of “fast food” began. Before long, billions were sold, and Kroc became one of Time magazine’s top 100 Persons of the 20th Century.2

Raymond Albert Kroc was born on October 5, 1902, in Oak Park, Illinois, a bustling suburb of German and Czech immigrants on Chicago’s West Side. Ray’s parents were Louis and Rose Mary (Hrach) Kroc. Louis was from Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic, and worked for Western Union. Rose’s father was an immigrant from Austria and she was born in Illinois. Rose gave piano lessons to support the family, which included Ray’s brother, Bob, and sister, Lorraine. They lived in their own home at 1007 Home Avenue, just two miles up the road from a young boy named Ernest Hemingway.3

Ray played baseball in the alley behind his house, where a garbage-can lid served as home plate, and players swung at a ball bandaged with black tape. “How agonizing it was though when my mother would step out onto the back porch and call, ‘Raymond! It’s time to come in and

practice,’” Ray remembered. The other boys would mimic her as Ray scooted off to his piano lesson. Louis would take young Ray to West Side Park to see the Chicago Cubs and their famous infield of Tinker to Evers to Chance. Joe Tinker and Louis were close friends, and a teenage Ray saw Babe Ruth and the Red Sox beat the Cubs in the 1918 World Series.

Ray’s ambitious nature earned him the nickname Danny Dreamer. In grammar school he started his own lemonade stand, then later worked at his uncle Earl’s drugstore and soda fountain. “That was where I learned that you could influence people with a smile and enthusiasm and sell them a sundae when what they’d come for was a cup of coffee,” Ray remembered. He and some high-school friends opened a short-lived sheet-music store. “I was the piano man, and I did a lot of playing and singing but not much selling.”4

Ray dropped out of high school and sold coffee beans door-to-door. “I was confident I could make my way in the world and saw no reason to return to school,” he said. He persuaded his parents to let him volunteer for the Red Cross to drive an ambulance during World War I. He lied about his age to do so. During training in Connecticut, Kroc and others partied around town at night while another boy his age spent his time drawing pictures. He was Walt Disney. Ray was ready to board a boat for France, but the Armistice was signed and the war was over. He came home and tried school again but soon dropped out again.

Ray started selling ribbon novelties. He also worked at a summer resort in Paw-Paw Lake, Michigan, playing the piano on a steamboat. He drew the attention of Ethel Janet Fleming, daughter of an engineer father and a mother who ran a hotel. A romance was started, but Louis Kroc forbade them to get married until Ray had a steady job. They married on June 2, 1922, after Ray became a salesman for the Lily-Tulip Paper Cup Company.5 Ray sold paper cups by day and played the piano nights for radio station WGES. He also hired talent at the station, including a comedic duo named Sam and Henry, who later became the legendary Amos & Andy. Kroc found a new customer in Bill Veeck, a young vendor at Wrigley Field, where fans realized paper cups were perfect for grabbing a beer during the game.

In 1924 Ray and Ethel had their only child, Marilyn. Ethel rarely saw Ray, who worked long hours and never grew close to his daughter. But he found time to attend ballgames and cheered on his Cubs in the 1929 World Series. Ray remembered seeing famous and infamous celebrities like Al Capone, Sophie Tucker, and Tommy Dorsey. The paper-cup business was going so well that Kroc bought a new Model T Ford and took the family to Florida, seeking to cash in on the real-estate boom. Ray worked for realtor W.F. Morang & Son but soon discovered that the investment properties he was selling were a scam. Out of a job, Ray worked in a nightclub that was raided by the police for violating Prohibition laws. The family soon returned to Chicago.

Ray drove to Wrigley Field in his Model A Ford at 2 A.M. on October 1, 1932, to get a ticket to the World Series. Kroc witnessed Babe Ruth’s alleged “called shot.” “I saw the motion,” Kroc remembered of the Bambino pointing, “but I don’t think he really called it. That was all in the minds of the sportswriters.”6

Returning to Lily-Tulip, Kroc worked his way up to Midwest sales manager by 1937. One major client brought new success to his paper-cup sales. Earl Prince ran the successful Prince Castle ice-cream parlors chain and Kroc’s paper cups were perfect for his milkshakes. Kroc became mesmerized by Prince’s new Multimixer, which could make six milkshakes at once. Kroc became Prince’s exclusive sales agent for this shiny new object in 1939. He spent the next several years traveling the country, selling the Multimixers to Tastee-Freeze and Dairy Queen.

By 1954 business had slowed since Hamilton Beach and other competitors sold their own multimixers and downtown soda fountains began to disappear. However, a hamburger drive-in in San Bernardino, California, had purchased eight of Ray’s Multimixers. Kroc went to visit this place, which was busy enough to make 48 milkshakes at a time, and talk to the owners, Maurice “Mac” and Richard “Dick” McDonald.

Mac and Dick were originally from Manchester, New Hampshire, the sons of a shoe-factory worker. They went west to California in the1920s, looking for fortune in the movie business. They purchased a rundown movie theater in Glendora. Successful initially, they suffered during the Great Depression and in 1937 sold the theater to run a hotdog and fruit stand they called the Airdrome near an airport in Monrovia. Success led to two more stands and in 1940 they opened a drive-in restaurant in San Bernardino. Patrons came for the popular McDonald’s Barbeque. In 1948 they upgraded their business model and their restaurant ran like an assembly line of burgers, fries, and milkshakes in 20 seconds.

Ray Kroc had never seen a restaurant like this before: It was clean, fast, and efficient. Customers came for the 15-cent hamburgers with warm french fries courtesy of infrared heating lamps. Kroc envisioned McDonald’s restaurants all over the country, and the brothers agreed to let him franchise their design for 1.9 percent of the gross sales. Dick and Mac would keep 0.5 percent as royalties. Ray opened his first store in Des Plaines, Illinois, in 1955. By 1960, there were 200 McDonald’s restaurants around the country. “Now the evolution of the hamburger has reached its zenith,” wrote Lucy Key Miller in the Chicago Tribune in 1957, “with the adoption of assembly line methods by Ray Kroc.”7

While discussing business over dinner at the Criterion restaurant in St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1957, Kroc heard beautiful music emanating from a Hammond organ. He was introduced to the organist, Joan Smith. “I was stunned by her blond beauty,” Kroc wrote. “Yes, she was married. Since I was married, too, the spark that ignited when our eyes met had to be ignored, but I would never forget it.”8

The two went their separate ways, but Ray’s own family was coming apart.

“As long-suffering Ethel became increasingly frustrated with her husband’s workaholic lifestyle, his reluctance to settle down, and his mortgaging of the family finances to underwrite his whimsical ideas, their daughter had sided with her mother, pained by her suffering,” Napoli wrote. “Home had not, for a long time now, been a welcoming, nurturing place for any of the Kroc family.”9

In 1958 Rawland F. “Rollie” Smith, Joan Smith’s husband, was managing a McDonald’s, which gave Ray an ample excuse to visit with Joan while “checking on business.” Their shared interest in music led to duets at the piano at the Criterion. She also saw a side of Ray she never saw before: the screaming baseball fan. They both were dressed to the nines while they sloshed through the mud after a storm to watch the minor-league St. Paul Saints.10 Ray continued to find the need to have extensive business conversations with Rollie and Joan. Rollie opened several McDonald’s in South Dakota. Despite both being married, Joan accepted Ray’s proposal for marriage in 1961.11 It was complicated.

Both Ray and Joan left their spouses and secured a house in Woodland Hills, California, then established residence in Las Vegas, waiting the six weeks to be able to legally marry. But Joan backed out after five weeks and returned to Rollie. Ray still went through with his divorce from Ethel, signed over the house, and agreed to pay $30,000 a year in alimony. Ray also had to part with his most crucial asset, the Prince Castle Sales Company he had created by selling his Multimixers. His employees bought him out for $150,000. At the time of the divorce, it was reported that Ray oversaw 323 hamburger stands in 37 states as chairman of McDonald’s Corporation.12

Ray also divorced himself from the McDonald brothers, asking to buy the company with all its trademarks and copyrights. The brothers asked for $2.7 million, which Kroc paid through a loan from Harry Sonneborn and a group of investors dubbed “the Twelve Apostles.”13

By the time all expenses of the deal were paid off in 1972, Kroc had spent $14 million. But that was a drop in the bucket considering the profits that would soon be made. The McDonald brothers retained sole rights to the original San Bernardino store, now called The Big M. Kroc didn’t like this, and soon new Golden Arches appeared across the street, and the brothers soon gave up the burger business.

In 1963 Ray met Jane Dobbins Green, John Wayne’s secretary. She was born Jane Elizabeth Dobbins to David and Grace (Duncan) Dobbins in Walla Walla, Washington, in 1911. “A rarefied whiff of glamour and refinement enveloped everything about the petite, elegant beauty: her golden blond hair, her stylish dress, her resemblance to Doris Day,” Napoli wrote. Jane had already had three marriages when she met Ray in California, who was taken by her “sweet disposition.”14 They were married on February 23, 1963, two weeks after meeting.

By 1966, McDonald’s was grossing $200 million yearly and was now public on the New York Stock Exchange. McDonald’s now boasted “Over 2 Billion Sold.” Hamburger University was created in 1961 as an employee training center. Their new mascot, Ronald McDonald, was portrayed by future Today Show weatherman Willard Scott. Kroc bought a 210-acre ranch he called the J and R Double Arch Ranch for $600,000 and created the Ray A. Kroc Foundation, managed by his brother Bob. The foundation focused on research for diabetes and arthritis, which afflicted Ray, and multiple sclerosis, which his sister Lorraine suffered from.15

Joan and Rollie attended a McDonald’s meeting in 1968, and Ray invited them to his suite. Ray and Joan rekindled their romance at the piano, while a frustrated Rollie stormed off. Ray and Jane had planned a cruise to celebrate their fifth wedding anniversary, but Ray lost interest. With McDonald’s executives present, Ray instructed his lawyers to break the news to Jane that he wanted a divorce and the trip was off. His chauffeur whisked him away as gathered guests consoled the devastated wife. Ray met Joan again in Las Vegas to establish residency.

She was born Joan Beverly Mansfield in August of 1928,16 in Saint Paul, Minnesota, to Charles and Gladys (Peterson) Mansfield. Charles was a railroad telegraph operator. Gladys played the violin and instilled in Joan a love for music. During the Great Depression, Charles took the family to California, where Joan’s only sister, Gloria, was born. The family soon moved back to St. Paul and Charles returned to the railroad. Young Joan fell in love with animals and she treated sick pets in the neighborhood. She also loved music and would travel by streetcar to the MacPhail School of Music in Minneapolis. As a teenager, Joan played and taught the piano.17 “Though other blondes may fade and tire, Joan will set men’s hearts afire,” was the caption in her high-school yearbook.18

After graduating, Joan worked at a hotel and bar in Whitefish, Montana, where she met Rollie, who had recently been discharged from the Navy. Rollie was fascinated with this young piano player and joined her in some songs at the piano. Six weeks later, on July 19, 1946, they were married. Their daughter Linda arrived on July 12, 1947, after the family had moved back to St. Paul. Rollie worked on the railroad while Joan taught keyboard, provided musical programming on KSTP-TV, as well as working at the Criterion restaurant.19

Both Ray and Joan terminated their marriages and got married on March 8, 1969. But when Ray returned to Chicago from business in 1971, he was issued a summons. Joan was filing for divorce. The court papers read, “The defendant has a violent and ungovernable temper and has in the past inflicted upon the person of the plaintiff physical harm, violence and injury.” The news hit the headlines, reporting Joan’s suffering “on the grounds of extreme mental cruelty.”20 The couple reconciled in early 1972, and the matter was never discussed again.

Joan celebrated Ray’s 70th birthday by donating $7.5 million to various museums and hospitals. “I was finding it increasingly difficult to keep up,” Ray confessed. “Some days I could hardly get around because of the way arthritis was warping my hip. Yet pain was preferable to idleness, and I kept moving despite Joni’s urging that we settle down on our ranch.”21 Ray wanted to stay busy but not have as grueling a schedule, so he returned to his childhood love of baseball.

“I wanted to own the Chicago Cubs, the baseball team I had been rooting for since I was seven years old,” he said. The Cubs weren’t for sale. But on the plane from Chicago to Los Angeles he read stories of the impending sale of the San Diego Padres. When Joan picked him up at the airport and he said he was considering buying the Padres, she asked, “What on earth is that? A monastery?”22

The San Diego Padres began as an expansion team in 1969. They were owned by Conrad Arnholt Smith, a California banker who had owned the team since 1955 when they were a minor-league club in the Pacific Coast League. Smith held a controlling interest in United States National Bank, which collapsed under a $400 million debt. Smith would later go to prison for embezzlement and commingling of funds from various businesses. It was revealed that President Richard Nixon’s former law firm had made secret deals with the Nixon administration to funnel assets from Westgate-California Corporation, owned by Smith, into the United States National Bank, to keep it from collapsing. Smith had raised over $1 million for the Nixon campaign.23

In May of 1973, it was announced that Smith had sold the Padres to supermarket magnate Joseph Danzansky and others in Washington, D.C., for $12 million. The new owners planned to relocate the club to Washington for the 1974 season. Baseball cards depicting the Padres players playing in Washington had already been printed. But antitrust and breach-of-contract lawsuits were filed against the National League by San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson and City Attorney John Witt. The Padres still had 15 years remaining on their lease of San Diego Stadium from the city. Kroc appeared with his lawyers on January 17, 1974, asking to review the team’s financial books.

It was the proverbial eleventh hour on January 23, 1974, and boxes were packed and ready to be moved to the nation’s capital. Kroc arrived to buy the club. “I’m hopeful it will work out, it looks very good,” he said. “Baseball is my sport. I want to have fun with an expensive hobby.” The Padres organization, desperate and on the cusp of uprooting, were now in the hands of a billionaire who just wanted a hobby. “And I can afford this expensive hobby,” he announced, with plans on keeping the franchise right where it was.24 “I won’t be an absentee landlord,” he promised. “I’ll be involved. I want our athletes to be proud men. I don’t feel I ever worked a day in my life —working is doing what you hate to do. I want ballplayers who enjoy baseball.”25

Two days after purchasing the club, Kroc negotiated a restructuring of the lease on San Diego Stadium, guaranteeing that the team would have a home through 1980. The final price to buy the club was $12 million. Buzzie Bavasi, team president, and his son, Peter Bavasi, general manager, would remain in their positions. “Now we can unpack,” a relieved Buzzie said.26 The move was approved by the National League a few days later. In early February, John McNamara was named the Padres’ new manager.

The Padres were coming off a 60-102 season in 1973, their third season of 100-plus losses in the first five years of the franchise, but had already added a future Hall of Famer in Willie McCovey. The ’73 Padres finished last in batting average (.244) and had the second-highest ERA (4.16) in the National League. They also ranked last in the league in attendance.

Opening Day was on April 5 at Los Angeles. Kroc went down to the Padres’ dugout to inspect his new “hobby.” “The important thing is,” he told McNamara, “that we hold our heads up and look like pros.” “I’m going to be patient,” he promised, despite the fact that he had never shown patience in building a fast-food empire. He didn’t have much patience earlier in the day, either, when he visited a local McDonald’s. “The food was terrible,” he griped. “I raised hell. It was a company store.”27 The Padres lost, 8-0, then continued to disappoint with 8-0 and 9-2 losses as they were swept in the opening series.

Their home opener was on April 9 against Houston. Kroc received a standing ovation during pregame ceremonies as fans showed appreciation for the man who kept their team in San Diego. He grabbed the mike and shouted, “With your help and God’s help, we’ll give ’em hell tonight.” But the Padres again looked like hell, trailing 9-2 in the middle of the eighth.

Kroc went into the public-address announcer’s booth, grabbed the mike, and yelled, “Ladies and gentlemen, I suffer with you.” Just then a naked man streaked across the field. “Get that streaker off the field and throw him in jail,” Kroc bellowed. “I have good news and bad news,” he continued. “The good news is that the Dodgers drew 31,000 for their opener and we’ve drawn 39,000 for ours. The bad news is that this is the most stupid baseball playing I’ve ever seen.” The crowd cheered, but Kroc was denounced for the outburst by players on both teams as well as Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and Players Association chief Marvin Miller. “I’ve never heard anything like that in my 19 years in baseball,” McCovey said. “None of us like being called stupid.”28

“I used a bad choice of words and I’m sorry,” Kroc said apologetically. “I was bitterly disappointed and embarrassed before almost 40,000 people. I should have said the team wasn’t playing good ball and have urged the fans to stick with us. At McDonald’s, we try to look out for the customers. It’s the same with our baseball fans. I want them to get value, to have a square deal and a fair deal.”29

Some weren’t satisfied with Kroc’s apology. “He knows as much about the sport as Willie McCovey knows about an Egg McMuffin,” slammed sportswriter Melvin Durslag. “The world is too quick to accept apologies as instant redress for mischief and atrocity,” Durslag said, ripping Kroc as another one of “the sports ignoramuses who have purchased franchises.”30

Kroc wanted his Padres to be the class of the league, even if he felt they were years away from being competitive. “I want it to be so that kids would rather play for the Padres than any team in the majors,” he said. “I’m going to buy the team a DC-9 and I would like for the team to stay in hotels that are at least a little better than the ones the other teams stay in.” Kroc also spent $60,000 in 1974 to field a team in the Arizona Fall League.31

One of Ray Kroc’s lasting legacies off the field also began in 1974 when he created the Ronald McDonald House. The facility, first begun in Philadelphia, was designed to provide housing for families with sick children who couldn’t afford to stay in nearby hotels or travel great distances. Families could give a donation of $5 per day or not pay at all if they could not afford it, as no family was ever turned away.

The Padres finished 1974 with an identical 60-102 last-place record as the previous year. However, the Padres fans supported the team; attendance was 1,075,399, eighth in the league. The team batting average dipped again to a league-worst .229 and pitchers had a league-worst 4.58 ERA.

The 1975 team improved to 71-91 and leaped to fourth place. Their batting average was tied for last (.244) and the Padres hit only 78 home runs, 23 by McCovey. But the pitching (3.48 ERA) was greatly improved behind Randy Jones’s 20 wins (league-best 2.24 ERA) despite no other starter winning more than eight. Attendance improved to 1.2 million fans (seventh).

Baseball entered a major turning point as pitchers Catfish Hunter and Andy Messersmith won free agency. Kroc might not have known how to grow talent from the ground up, but he knew how to open his wallet on the open market. He made bids for both, but both went elsewhere.32 Kroc anticipated more free agents being available after the 1976 season.

While waiting for new baseball players, Kroc decided to add professional hockey to his list of hobbies. In August of 1976 he purchased the fledgling San Diego Mariners of the World Hockey Association for $450,000.33 He felt San Diego needed all four major sports, even if he himself knew little about hockey. “They were going to leave town,” he said, “and it wouldn’t be good for the town to lose hockey. At first I was going to loan some money to the hockey team. But I decided I’d rather own it. If I’m going to lose the money, I’ll own it and lose it rather than loan it and lose it.”34 Ray and Joan sold their Fort Lauderdale home and moved to the La Jolla section of San Diego.

On July 4, 1976, the Padres were 42-37 and in third place, but they went 31-52 from that point on, finishing 29 games back in the division at 73-89. Despite the late-season woes, this was still the most wins in franchise history. Jones (22-14) won the NL Cy Young Award. The team continued to draw well; 1.4 million came out to the park, fourth best in the league.

After the season Kroc gave $1.25 million and a six-year deal to veteran free-agent catcher-first baseman Gene Tenace. “He’s Kroc’s favorite player,” Buzzie Bavasi explained of Oakland’s popular player, “and what Kroc wants, he usually gets.”35 Kroc also wanted slugger Reggie Jackson, but a $3 million deal for five years was not enough and Jackson signed with the Yankees. Disappointed but not defeated, Kroc signed another Oakland star, bullpen ace Rollie Fingers36 and veteran outfielder George Hendrick. On paper, the Padres appeared to be a contender.

Kroc resigned as chairman of the board of McDonald’s in late September 1976 but continued as senior chairman.37 Also in 1976, Joan first stepped into the world of philanthropy. She brought publicity to alcoholism, a disease few would ever publicly discuss at the time. She founded CORK (Kroc spelled backwards), an organization that worked with families of alcoholics. There was more than one meaning to the name: The secret everyone knew but Ray refused to admit was his alcoholism. Wanting to help families that suffer through a member’s alcoholism, Joan recruited advice columnist Abigail Van Buren (“Dear Abby”) to publicize the organization, and thousands of readers sent in donations. CORK had a $1 million operating budget in 1978 and provided an $800,000 grant to the Dartmouth Medical School to develop a curriculum for studying alcoholism. “Our main focus is on the family members of the country’s 10 million alcoholics,” Joan said. “For each alcoholic in a family, four or five family members are being severely affected. We want to show them what they can do, and how they can get help. I’m just not business-oriented,” she said, distinguishing herself from Ray. “I have a good head, and I’m logical, but my real concern is for human problems.”38 Joan also funded made-for-TV movies dealing with the subject. She was part of a cultural revolution, while hiding the secrets at home of why this topic was so important to her.

The best team Ray thought money could buy had fallen apart before Memorial Day 1977. With the Padres limping along at 20-28 and already 14½ games behind the division-leading Dodgers, McNamara was fired. “In all of baseball there’s not a finer man than Mac,” Kroc said. “He is a gentleman among men. Everybody thinks this is a glamorous business, but it can be very tough. I’m tough on the outside, but I’m soft on the inside. Mac is a very wholesome guy but we’re in the baseball business, not the fellowship business. The players by their performances have shown us we aren’t getting the leadership we need.”39 Kroc’s new manager was Alvin Dark, the former Oakland manager who had been on the Cubs coaching staff. The team played better under Dark (48-65), but it was a lost season at 69-93. Fingers led the league in appearances (78) and saves (35), but the team ERA (4.43) was second worst in the NL. While Hendrick (.311/23/81) and Dave Winfield (.275/25/92) provided power in the lineup, the .249 team average was also next to last. Attendance dropped to 1.3 million.

If the Padres were a disappointment, Kroc’s hockey ventures were even worse. He sold the Mariners in May to an ownership group in Florida that couldn’t secure a stadium, so the team folded. Kroc lost $1.4 million on the club.

In September 1977 Kroc named himself the Padres’ president after Bavasi resigned. Kroc’s son-in-law Ballard Smith became executive vice president. GM Bob Fontaine would have the final say on trades. “I’m going to take over,” Kroc said, “and I’m going to turn this club inside out.”40 Kroc doubled the television revenue to $200,000 and the radio revenue to $360,000.41 To try to boost the lineup and attendance, Kroc signed outfielder Oscar Gamble to a six-year contract for $2 million.

Despite $3.3 million in ticket revenues, the Padres suffered a net operating loss of $2.1 million in 1977. “San Diego has given the ballclub marvelous support over the past four seasons,” Ballard Smith said, “but Ray is just about even at this point. We went into the 1977 season with cash reserves of $1.8 million. That’s gone. People have the impression Ray is making a lot of money off the Padres, but that is hardly the case. My ambition right now is to see that we break even this year.”42 Contradicting themselves, the Padres acquired 39-year-old pitcher Gaylord Perry and 37-year-old pitcher Mickey Lolich. In early February 1978, Kroc purchased for the team a 727 jet from Northwest Airlines for $4.5 million.43 So much for breaking even.

Kroc fired manager Alvin Dark in spring training after a player revolt. “Alvin had a tendency to overmanage,” Kroc said. “It was too much.”44 Pitching coach Roger Craig became the manager. The change didn’t result in success and the Padres were under .500 for much of the season in 1978. “The crybaby ballplayers complained about Alvin Dark, and they get Roger Craig, who’s the epitome of a great guy on and off the field. And they’re playing for him like they played for Alvin,” Kroc ranted. “Roger Craig can’t make up for a bunch of guys who don’t give a damn and don’t work at it. I’m sick and tired of the way this ballclub has been playing. It’s pitiful. I’m thoroughly disgusted. I don’t think they’ve got any guts or pride. They may not give a damn, but I’ve got news for them —I do. I want ballplayers. I’m not going to subsidize idiots. I don’t know what these guys want. You give them a private plane, a players’ lounge, everything under the sun. And they still respond like juveniles.” Kroc singled out Tenace. “He needs to go to an eye doctor. He can’t tell a strike from a ball. He hasn’t given this club one thing since we got him. Tenace is the most overrated player on this team —he’s a disgrace.” Kroc later retracted the comments, saying, “I was probably a little hard on Gene. He’s a perfect gentleman and he has a good attitude.”45

Kroc and San Diego hosted the 1978 All-Star Game with 51,549 on hand, the largest crowd to see a baseball game in San Diego at that point. The team went 42-33 in the second half of the season to finish fourth at 84-78, with attendance at just over 1.6 million (fifth). This was the first team to finish above .500 in the history of the franchise. Perry (21-6) won the NL Cy Young Award, but Gamble, his production dropping from 31 home runs to seven in 1978, was traded away to save money. When asked if his team played better since he bought them their own airplane, Kroc said, “They play the same whether they ride in an airplane or a mule-drawn cart. And I’m not sure some of them know the difference.”46

In November Kroc flew to Tokyo for the opening of his 5,000th McDonald’s.47 The business of baseball was much more difficult. “When I was selling, I always believed each new year would be a high for me,” he said. “I’d be a year older, I’d have more experience and be more knowledgeable. Now, why can’t ballplayers be like that? Why do they suddenly want to be paid before they achieve their goals? I can’t understand that. Some of the risk has got to be borne by the individual. You have to do it first. You can’t get paid first.”48

The 1979 team did not follow the previous year’s success, and on August 13 were 53-66. Kroc, who publicly stated he had lost money every year since he bought the club, promised more shakeups. “Whatever we’ve done is not good enough. I want to do better,” he said. Roger Craig was fired in the offseason. Kroc made headlines when he promised to “spend $5 million to $10 million” to “try signing Graig Nettles and Joe Morgan if they become free agents this fall. You bet your boots I’m going after ’em.”49

For these statements, Kroc was fined $100,000 by the league for player tampering. “Baseball has brought me nothing but aggravation,” Kroc complained. “It can go to hell.”50 He gave up control of day-to-day operations to Ballard Smith. “There’s a lot more fun in hamburgers than baseball,” Kroc said. “The fun in it is all gone for me. Baseball isn’t baseball anymore. I’ve been disillusioned by everyone I met.”51 Kroc contemplated selling the team. “I’ve never seen him so depressed,” Joan said. But he changed his mind. “I can’t get out of baseball,” he said. “It means so much to me. I’ll keep the club another five years and give it a try.”52

Kroc brought in free-agent pitchers Rick Wise and John Curtis and traded for second baseman Dave Cash. Jack McKeon was hired as assistant general manager, and Padres broadcaster Jerry Coleman became manager. Kroc suffered a stroke just before Christmas of 1979 and had to curtail his drinking habits. Coleman’s tenure lasted just a year as the Padres finished back in last place (73-89) in 1980. The season was overshadowed by the impending free agency of Winfield. The future Hall of Famer was seeking a 10-year contract for over $1 million per season. “Who’s going to pay him?” Kroc asked. “I’m not going to pay him. The customers aren’t going to pay him. He doesn’t mean a damn thing.”53 The Yankees felt otherwise and gave all that and more to make the star outfielder the highest-paid player in the game.54

Kroc reported he had lost $2.7 million in 1980 as rumors of a players strike circulated in early 1981. “It’s ridiculous,” he said. “I have a (Kroc) Foundation that gives $5 million a year to fight diseases like multiple sclerosis and arthritis. They haven’t found the cures yet, but at least I can feel like that money is doing some good. I don’t get that feeling in baseball anymore. I said when I got into this business that the last thing I needed was another dollar’s worth of income. I’ve never taken a penny out of the ballclub. I decided long ago that I’d just write the Padres off (tax-wise). I don’t want to sell them. I wouldn’t even mind losing $50,000 to $100,000 a year with them. But $2.7 million is ridiculous.” He believed his free-agent signings of Fingers, Tenace, Gamble, Wise, and Curtis were a waste of money along with the team jet, which he decided to sell.55 Frank Howard lasted only the strike-shortened 1981 campaign as manager, as the Padres finished last in both halves.

Ballard Smith and Jack McKeon, who began earning his nickname of Trader Jack, were busy after the 1981 season. They shipped out Fingers, Tenace, and pitcher Bob Shirley in a 10-player trade with St. Louis, receiving promising young catcher Terry Kennedy. Young speedster Alan Wiggins was taken in the Rule 5 draft and young pitchers Tim Lollar and Dave Dravecky emerged. They also traded Gold Glove shortstop Ozzie Smith to St. Louis for veteran shortstop Garry Templeton. Dick Williams, who had success previously in Boston, Oakland, and Montreal, became the Padres’ new manager.

Kroc celebrated an early 80th birthday at the newly renamed Jack Murphy Stadium on October 2. The team finished the 1982 season 81-81, eight games behind division winner Atlanta. The Padres were second in stolen bases, fifth in ERA, and first in defensive efficiency. Four players had 27 or more stolen bases, and a 22-year-old rookie named Tony Gwynn was called up in July, the first of his 20 Hall of Fame seasons in San Diego.

Still lacking in star power, the Padres in late December made headlines when they signed first baseman Steve Garvey to a five-year, $6.5 million contract. “Steve, I think you can make a difference here,” Kroc said to Garvey when they met at Kroc’s home.”56 On his way to the podium for the press conference, Garvey stopped and greeted Ray and Joan. “We’re going to have some fun. We’re going to have a winner,” he promised.57

The 1983 season was an identical 81-81 record for the Padres as Garvey was limited by a thumb injury. Meanwhile, McDonald’s reported $8 billion in sales and Kroc’s fortune was now estimated at $500 million. Ray was hospitalized for 10 days in September, returned home, and then was readmitted on December 5. Needing a closer but unsure if the team could afford one, Smith and McKeon visited Ray in the hospital. When McKeon said he thought Goose Gossage could help the team win the pennant, Kroc responded, “Sign him.”58 On January 6, 1984, Ray had a visitor at the hospital. It was Gossage, who had just signed with the Padres for what was reported as the largest contract ever given a pitcher: a five-year deal for $6.25 million.59

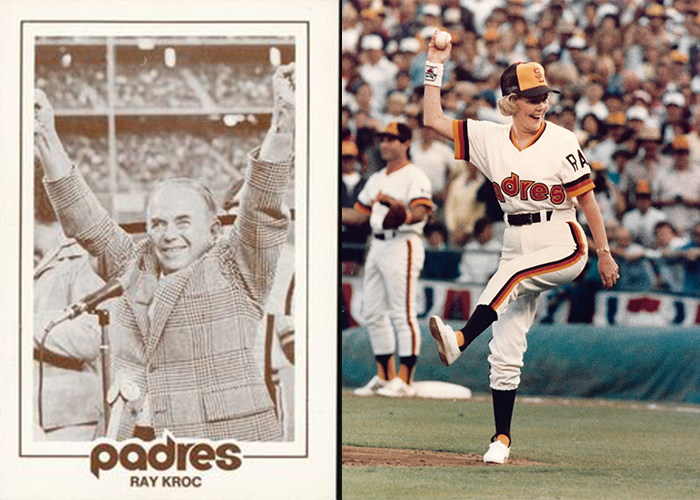

Ray would never return home. He died of heart failure on January 14 and was buried in El Camino Memorial Park in San Diego.60 The Padres wore a patch on their sleeve that season with the initials “RAK” in his memory. By the time of his death, McDonald’s was grossing $12 billion per year in sales through its 9,400 restaurants.61 “Ray Kroc was many things,” wrote Bud Poliquin of the San Diego Union-Tribune. “Philanthropist. Entrepreneur. An internationally known figure. But beyond all of that, beyond the fortune he accumulated through his development of the McDonald’s restaurant chain, he was a hot-dog-eating, peanut-shelling, foot-stomping baseball fan.”62 Joan Kroc now controlled a baseball team.

Ray didn’t live to see the Padres finally acquire Nettles, years after the $100,000 tampering incident. The veteran was now 39 but provided power at the plate and presence in the clubhouse, along with Garvey and Gossage. Ray also didn’t live to see his dream of the Padres playing in the World Series. Everything came together for the 1984 team. Gwynn (.351) won the NL batting crown and Wiggins stole 70 bases. The team led the league in defensive efficiency. Young outfielders Carmelo Martinez and Kevin McReynolds were hyped as the new “M&M Boys,” combining for 33 home runs. Lollar (11 victories), Ed Whitson (14), Mark Thurmond (14), and Eric Show (15) gave the Padres four starting pitchers with double-digit wins. Gossage was supported in the bullpen by a cast of low ERAs: Dravecky (2.93), Craig Lefferts (2.13), Greg Booker (3.30), and Greg Harris (2.70). “When I took over, I had a five-year plan, and I thought we would win by 1985,” McKeon said. “We’ve gotten there earlier than I expected because Ballard and Joan were able to spend the money to sign free agents like Steve Garvey and Goose Gossage.”63

The Padres took over first place for good on June 9 and never looked back, winning the NL West by 12 games. In what would have been a bittersweet time for Ray, they played his first love, the Cubs, in the National League Championship Series. The Padres dropped the first two games in Chicago but swept the next three to get to the World Series. Whitson guided the Padres to a Game Three win, the first playoff game ever in San Diego. Game Four would go down as a classic. Leading 5-3 in the top of the eighth, Gossage couldn’t hold off the Cubs, who scored two to tie. With Cubs closer Lee Smith on the mound, Gwynn singled, then Garvey hit a walk-off home run to right field to send the series to a decisive Game Five. The Cubs jumped out to a 3-0 lead, but four Padres relievers shut the door from then on. With the Padres trailing 3-2 in the bottom of the seventh, Cubs first baseman Leon Durham let a grounder go between his legs to allow the tying run to score. The Padres then tagged three straight hits off Rick Sutcliffe to score three more runs, and prevailed, 6-3.

“We dedicated this season to Ray and that’s why we’re in the World Series today,” Joan said. “This team was committed, they were determined, they have the best fans in America, they worked harder than anybody —I could go on and on. Any team could win if they had what we’ve had this year.”64 The Padres lost to the heavily favored Detroit Tigers in five games in the World Series. They would not see the postseason again for 12 years.

During their championship season, two off-field incidents tested Joan’s leadership abilities. In July, pitchers Show, Dravecky, and Thurmond each revealed that they belonged to the ultra- conservative John Birch Society, known for its anti-Semitic and racist views. Joan believed the clubhouse was no place to air political commentary and that it risked alienating teammates and fans. “I’m concerned about our team being a forum for political beliefs and aspirations,” she said. “It has nothing to do with sport —and I don’t think the boys mean it to be —but I think it should be dropped. Anybody who knows anything about politics knows that the John Birch Society is a radical —let’s say … controversial —organization. And sports isn’t the place to get into controversial politics. The clubhouse is not a place for it.”65 Decades later, Dravecky said the trio had no idea about the racist overtones of the society and were drawn to its conservative small-government ideals.66

On July 18, 1984, gunman James Oliver Huberty entered a McDonald’s in the San Diego neighborhood of San Ysidro and opened fire, killing 21 people and injuring 19 before being taken down by a SWAT team. It was the largest mass shooting in US history at the time. Joan donated $100,000 of aid for survivors and families of the victims, while McDonald’s Corporate donated $1 million. “The only thing I thought about McDonald’s in that regard was, ‘Thank God, Ray never lived to see it,’” Joan said. “Because he wouldn’t have believed that something like that could have happened at all.”67 Some were angered when Joan also contributed to Huberty’s wife and children. “Surely everyone would agree that this compassion must extend to Mrs. Huberty and her two children,” she said, “so that they too can begin to rebuild their shattered lives.”68

Joan was now out of the Ray’s shadow, although she had been involved in numerous charities herself over the years. She had always let Ray do the talking throughout their public appearances. “I’ve always been opinionated and committed to things I believe,” she said, “but I didn’t feel the need to espouse them to the world. Anytime you are involved with a man like Ray, who was so charismatic and strong, you can’t have two people vocalizing at once. Politically, we were at separate ends of the spectrum. [He was a staunch Republican; she a registered Independent.] It wouldn’t have been ladylike or proper to differ with him at public forums.” Joan was now felt free to articulate her own beliefs. “Two words I wish we could remove: guilt and regret,” she pronounced. “We all make mistakes and we all do things we wish we hadn’t. What good do guilt and regret do? They’re counterproductive. We have to move forward. (Life) is no kinder to one person than the other.”69

In July of 1984, Joan sold 300,000 shares of McDonald’s stock for well over $20 million, but she still owned over 6 million shares, or 10.5 percent of the holdings.70 Ballard Smith had already become a member of the McDonald’s board of directors, where he would remain until 1997. In December the Joan B. Kroc Foundation donated $1 million to famine relief in Africa.71

One of Joan’s primary causes was nuclear disarmament. In April of 1985, she was in the audience to hear a speech by Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, the former president of the University of Notre Dame. She was impressed with his vision of a nuclear-free world and peace. She had several meetings with Hesburgh over the next few months. In December, she donated $6 million to create “a center for multidisciplinary research and teaching on the critically important questions of peace, justice, and violence in contemporary society.” The Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at Notre Dame was created, thanks in part through her donation of $69 million.72 “To me, the nuclear freeze issue transcends politics,” she said. “We live in a world in which nuclear weapons are casting a pall of fear and helplessness over us that may be as tragic as their detonation.”73 The institute awards academic degrees and says its alumni are “at all levels of society to build a more just and peaceful world.”74

The remainder of Joan’s years as owner of the Padres never reached the heights of 1984. In 1985 Wiggins was dealt to Baltimore after being connected to drug use, violating Joan’s zero-tolerance policy. The team dropped to third (83-79) and friction emerged in the front office. McKeon and Smith offered to buy out Dick Williams’s contract, unbeknownst to Kroc, who denounced the move. “That will never happen,” she said. Smith and McKeon will “have to use their own money because I’m not using mine. There is something inherently indecent about buying out contracts in this kind of situation. If Dick chooses to walk away, not only will that sadden me, but he will walk away empty-handed. And I don’t expect him to do that.”75

Williams resigned during spring training, or was forced out, depending on who you believed, and Steve Boros took over as manager in 1986. The Padres again finished fourth (74-88) and star pitcher Lamarr Hoyt was also shipped out after the discovery of drugs. Kroc also forbade drinking in the clubhouse, which led to a suspension of Gossage. “She’s poisoning the world with her cheeseburgers and we can’t have a beer after a game,” Gossage said. The two later reconciled. “I said something very disrespectful and she fired right back at me. She was as tough as she was nice … and she was probably the nicest, kindest lady I ever knew. At the end of that meeting, we hugged.”76

At the end of the 1986 season, Kroc put the Padres up for sale, but sought a buyer who would keep the club in San Diego. The lease on Jack Murphy Stadium, however, was extended by the city until the year 2000. Ballard Smith resigned as team president as he and Linda were filing for divorce.77 The Padres fell to last place (65-97) under new team President Chub Feeney and manager Larry Bowa, who was fired after the club started 16-30 in 1988. McKeon managed the remainder of the season and in 1989 when the team improved (89-73). In April of 1990 Joan sold the Padres to television producer Tom Werner and nine other partners for $75 million. Werner had produced such television hits as The Cosby Show and Roseanne.78

In 1997 Joan anonymously donated $15 million to flood victims in North Dakota and Minnesota. A reporter nevertheless discovered she was the source of the gift, and she was dubbed the Angel of Grand Forks, but she declined to receive any public recognition. Her net worth was estimated at $2.1 billion by 1998. She donated $87 million to the Salvation Army for a 12-acre youth center in San Diego. Only at the urging of friends did she publicly reveal herself as the benefactor. She often said her giving was a continuation of Ray’s generosity. “Ray was once asked why he gave so much of his wealth away,” Joan said. “He said, ‘I’ve never seen a Brinks truck following a hearse.’ Have you?”79

“When she walked into a room, she radiated joy,” said San Diego Mayor Maureen O’ Connor.80 Joan contributed to homeless shelters, AIDS and cancer research, the Special Olympics, and the Betty Ford Center. She contributed $25 million to the University of San Diego to establish the Mohandas K. Gandhi Institute for Peace and Justice.81 Her $100 million donation expanded the Ronald McDonald House into the broader Ronald McDonald Charities, which as of 2018 included 365 Ronald McDonald Houses in 43 countries and regions and 50 mobile medical-care units, and provided assistance to 5.5 million children and families around the world.82 She donated $1 million to the Democratic Party and $2 million for the construction of the Kroc-Copley Animal Shelter.

Lisa Napoli spends nearly eight pages documenting Joan’s various financial donations, even though it is not nearly an exhaustive list.83 Her life was one of philanthropy and when Joan died of brain cancer on October 12, 2003, at the age of 75, money continued to be distributed according to her wishes. She bequeathed $1.5 billion to the Salvation Army, $225 million to National Public Radio, and $60 million to the Ronald McDonald Charities. The University of San Diego and the University of Notre Dame, where she established peace initiatives, each received $50 million.

“Joan Kroc could have used the fortune that she and her husband amassed to insulate herself,” said the San Diego Union-Tribune. Instead, she became very involved with a variety of good works that have benefited countless people. Those who were fortunate enough to have known her marveled at her unpretentiousness. This wonderful woman, who wasn’t born to wealth, never stopped believing she should use much of her treasure to help others. The many lives she touched in so many ways will remain her enduring legacy.”84

Sources

Special thanks to Cassidy Lent, reference librarian at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, for providing access to the Krocs’ extensive files. Other sources include:

Associated Press. “‘Fanatic’ Set to Ante $10 million,” January 1974 article of unknown origin in Kroc’s Hall of Fame File.

Associated Press. “Padres Moving to Washington,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 28, 1973: 47.

Baseball-reference.com.

Boas, Max, and Steve Chain. “Mr. Mac: Maestro of Munchland,” Daily News (unknown place of origin), June 1, 1976: C9. Article is from Kroc’s Hall of Fame file.

“Kroc Hospitalized After Stroke,” San Diego Union, January 3, 1980: F1.

“Life and Times of Joan B. Kroc,” San Diego Union, October 13, 2003: A12.

Retrosheet.org.

Photos: Courtesy of the San Diego Padres and Andy Strasberg Collection.

Notes

1 Nancy Ray and Dave Distel, “Ray Kroc, 81, Builder of McDonald’s Chain, Dies,” Los Angeles Times, January 15, 1984: 1.

2 content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,26473,00.html Retrieved May 5, 2018.

3 Hemingway, born in 1899, lived at 600 North Kenilworth.

4 Ray Kroc and Robert Anderson. Grinding It Out: The Making of McDonald’s (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1977), 13.

5 Kroc and Anderson, 14-19.

6 Kroc and Anderson, 24-25.

7 Lucy Key Miller, “Front Views & Profiles,” Chicago Tribune, October 29, 1957: F5.

8 Kroc and Anderson, 113.

9 Lisa Napoli, Ray & Joan: The Man Who Made the McDonald’s Fortune and the Woman Who Gave It All Away (Boston: E.P. Dutton, 2016), 55.

10 Napoli, 64-65.

11 Napoli, 81.

12 Napoli, 88-92; “Wins Divorce, $30,000 a Year, $100,000 House,” Chicago Tribune, April 19, 1962: F4.

13 Napoli, 94; Kenan Heise, “Ex-McDonald’s Exec Harry J. Sonneborn, 77,” Chicago Tribune, October 6, 1992.

14 Napoli, 97.

15 Napoli, 108-109.

16 According to Napoli, Joan Kroc always claimed August 27 as her official birth date even though August 26 is given on the birth certificate. Napoli, 42.

17 George Flynn, “San Ysidro Tragedy Struck at the Heart of Joan Kroc,” San Diego Union, July 29, 1984: B1.

18 Napoli, 44.

19 Napoli, 45.

20 Napoli, 130; United Press International, “Executive Sued for Divorce,” Indianapolis Star, November 12, 1971: 55.

21 Napoli, 175.

22 Napoli, 176.

23 Holcombe B. Noble, “C. Arnholt Smith, 97, Banker and Padres Chief Before a Fall,” New York Times, June 11, 1996; Denny Walsh and Tom Flaherty, “Tampering with Justice in San Diego,” Life, March 24, 1972: 30; “Arnholt Guilty of Evading Taxes,” Washington Post, May 4, 1979.

24 Jack Murphy, “Kroc Agrees to Purchase Padres, Seeks League’s OK,” San Diego Union, January 24, 1974: 1.

25 Murphy, D4.

26 Phil Collier, “City, Kroc, OK Stadium Lease; Padres to Stay,” San Diego Union, January 26, 1974: 1.

27 Jack Murphy, “Kroc Is Brimming with Pride and Patience,” San Diego Union, April 6, 1974: C1.

28 Phil Collier, “Kroc Rips Club on P.A. as Astros Romp, 9-5,” San Diego Union, April 10, 1974: C1.

29 Phil Collier, “Padre Kroc Eats Humble Pie After ‘Stupid’ Slur,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1974: 25.

30 Melvin Durslag commentary of unknown origin marked May 4, 1974, from Kroc’s Hall of Fame File.

31 Phil Collier, “Kroc Goal for Padres: That Old Yank Pride,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1974: 8.

32 Jack Murphy, “He Loses Messersmith But He’s Not Defeated,” San Diego Union, April 12, 1976: C1.

33 Jack Murphy, “It’s Official: WHA Okays Kroc’s Mariner Purchase,” San Diego Union, August 10, 1976: C1.

34 Charles Maher, “Ray Kroc. McDonald’s Magnate Makes His Break to be Near Padres,” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1977.

35 Phil Collier, “Tenace Accepts Padres’ Pact,” San Diego Union, November 17, 1976: C1.

36 Jack Murphy, “Signing Fingers Brightens Kroc’s Thanksgiving Day,” San Diego Union, November 26, 1976: C1.

37 “Dow Jones Reports,” San Diego Union, September 30, 1976: B6.

38 Judy Klemesrud, “For Alcoholics, Treatment in a Mansion … and a Program for the Families,” New York Times, July 10, 1978: 9.

39 Jack Murphy, “Kroc Asserts Himself, and McNamara Is Gone,” San Diego Union, May 29, 1977: H1.

40 Jack Murphy, “Bavasi Out as Padres’ President,” San Diego Union, September 21, 1977: 1.

41 Phil Collier, “Padres Drag in More Loot from Radio and TV,” The Sporting News, January 28, 1978.

42 Jack Murphy, “$2.1 Million Deficit for the Padres in ’77,” San Diego Union, January 23, 1978: C1.

43 “4 Padre Players Reported Signed,” San Diego Union, February 10, 1978: C1; Jack Murphy, “Air Kroc’s Inaugural Flight a Happy Event,” San Diego Union, April 25, 1978: C1.

44 Phil Collier, “Padres Name Craig to Succeed Fired Dark,” San Diego Union, March 22, 1978: C1.

45 “Kroc’s Timing Off by a Day,” article of unknown origin in Kroc’s file, labeled June of 1978; Dave Distel, “‘Offend the Players? They Offend the Fans,’” Globe-Democrat-Los Angeles Times News Service. Article of unknown date in Kroc’s Hall of Fame file.

46 “Insiders Say,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1978: 4.

47 Dick Young, “Ideas,” article of unknown origin in Kroc’s Hall of Fame file marked 11/11/78.

48 Steve Bisheff, “Baseball Too Protective of Weaker Sisters, Says Big Brother Kroc,” The Sporting News, May 12, 1979: 9.

49 Associated Press, “Padre Shakeup in Works,” article of unknown origin in Kroc’s Hall of Fame File marked 8-14-79.

50 Phil Collier, “Kroc’s Tampering Penalty: $100,000,” San Diego Union, August 24, 1979: D1.

51 Murray Chass, “Kroc, Citing $100,000 Fine, Gives Up Control of Padres,” New York Times, August 25, 1979.

52 Jack Murphy, “Kuhn Almost Drove Kroc From Baseball,” San Diego Union, August 30, 1979: D1.

53 Phil Collier, “Kroc: Winfield Out,” San Diego Union, August 6, 1980: C1.

54 Phil Pepe, “Winfield a Yankee for 10 Years, $13M,” New York Daily News, December 16, 1980: 88.

55 Phil Collier, “Upset Kroc Won’t Sell Padres,” Sporting News, March 28, 1981: 28.

56 Garvey, quoted in “Triumph and Tragedy: The 1984 San Diego Padres.” Major League Baseball Network. Retrieved April 29, 2018. youtube.com/watch?v=W-GVrkSmEPs.

57 Phil Collier, “Steve Garvey Is Now a Padre,” San Diego Union, December 22, 1982: 6.

58 “Triumph and Tragedy.”

59 Phil Collier, “Padres: ‘Goose’ Signs on for Five-Year Stint —Gossage for $6.25 Million,” San Diego Union, January 7, 1984: C1.

60 Eric Pace, “Ray A. Kroc Dies at 81; Built McDonald’s Chain,” New York Times, January 15, 1984; Tom Blair column, San Diego Union-Tribune, September 29, 1983: B1.

61 Kroc and Anderson, 205.

62 Bud Poliquin, “Ray Kroc: a Fan and a Friend,” San Diego Union-Tribune, January 16, 1984: C1.

63 Phil Collier, “Title Brings Thoughts of Kroc and Struggle,” San Diego Union-Tribune, September 21, 1984: C10.

64 Mark Sauer and Ed Jahn, “Dreams Can Come True —Padres Win Flag for Kroc —Series Opens Tomorrow – Delicious, Delightful Delirium,” San Diego Union, October 8, 1984: A1.

65 Nick Canepa, “Birch Comments Stir Concern —Kroc, Smith Worry About Club’s Image,” San Diego Union- Tribune, July 13, 1984: E1.

66 “Triumph and Tragedy.”

67 Suzanne Choney, “Joan Kroc —A Year of Wins, Losses,” San Diego Union-Tribune, October 19, 1984: A1; Christopher Reynolds, “McDonald’s Will Establish Fund,” San Diego Union-Tribune, July 20, 1984: A14.

68 Flynn, “San Ysidro Tragedy.”

69 Choney.

70 Donald Coleman, “Largest Shareholder —Joan Kroc Sells Block of McDonald’s Shares,” San Diego Union- Tribune, October 23, 1984: A17.

71 Frank Green, “Joan Kroc Gives $1 Million in Famine Aid,” San Diego Union, December 12, 1984: A14.

72 “History,” kroc.nd.edu/about-us/history/, retrieved April 28, 2018; “Joan B. Kroc’s Legacy,” kroc.nd.edu/about- us/history/joan-b-krocs-legacy/, retrieved April 28, 2018.

73 Choney.

74 “About Us,” kroc.nd.edu/about-us/ retrieved April 28, 2018.

75 Bob Slocum, “The Buyout Fiasco —Kroc Insists on Honoring Williams’ Contract,” San Diego Union, December 4, 1985: C1.

76 Bill Center, “Padres of Yesterday Remember Kind, Caring Lady Who Led Team,” San Diego Union, October 13, 2003: A13.

77 Mark Kreidler, “Joan Kroc Will Keep the Padres,” San Diego Union, May 30, 1987: A1.

78 Mark Kreidler, “Joan Kroc to Sell

Full Name

Raymond Albert Kroc

Born

October 5, 1902 at Oak Park, IL (US)

Died

January 14, 1984 at San Diego, CA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.