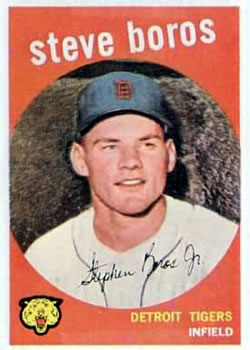

Steve Boros

An average major-leaguer and a professorial manager who tried to treat his ballplayers like grown men, Steve Boros was a baseball lifer whose career spanned over two dozen teams across six decades. Broadcaster Ernie Harwell called him “one of the most cerebral baseball men I’ve ever known.”1

An average major-leaguer and a professorial manager who tried to treat his ballplayers like grown men, Steve Boros was a baseball lifer whose career spanned over two dozen teams across six decades. Broadcaster Ernie Harwell called him “one of the most cerebral baseball men I’ve ever known.”1

Born September 3, 1936, in Flint, Michigan, Stephen Boros Jr. grew up the eldest of five children in a strong Hungarian-American family. His father and namesake reached the United States alone as a teenager in 1926, and his mother, Helen Boka, was the daughter of Hungarian immigrants. Stephen Sr. worked in an auto-body plant before the couple opened a small grocery in 1946. The family lived above the store.

Steve Jr. grew up a book-loving jock, the star shortstop of an American Legion team that won a state title in 1952. He played football, basketball, and baseball as a six-foot, 185-pounder at Flint North High School. After participating in a 1954 all-star baseball game for under-18 players from Detroit and Buffalo, he went on to play college ball 50 miles from home at Ann Arbor.

“I wasn’t much in high school,” he said later. “I just had no confidence that I would ever make the grade as a ball player. But I entered the University of Michigan and going to college seemed to build up my confidence.”2

Calm and soft-spoken, Boros planned to become a pharmacist but soon switched to the liberal arts. During two seasons as a varsity ballplayer, he hit .324 and .381 as Michigan went 36-16 overall. He was an All-Big Ten third baseman in 1957, elected as team captain for the following season. Then unexpectedly he accepted a $25,000 offer from the Detroit Tigers to turn pro.

“Major league baseball is a cut-throat game, and they are cutting their own throats as well,” UM coach Ray Fisher said angrily. “Boros told me he didn’t intend to sign. He’s a good hitter and has power as good as Dick Wakefield’s when he connects.”3 But Boros had good cause for leaving. “I can’t afford to keep him in school any longer,” his father said.4

The Tigers later set up a college scholarship fund for players in similar straits. Boros would earn his bachelor’s degree in English by studying at odd hours during and between seasons. All his siblings would graduate, too. One became a pharmacist, another a landscape architect, and two became teachers.

Under 1957 rules, any player with a bonus of $4,000 or more had to spend two years with the big club. Thrust into fast company, Boros made his big league debut June 19 and got his first hit three days later, a single in a 13-inning game at Baltimore. But he hit only .146 during 24 games in the American League before heading abroad for winter ball in Mexico’s Veracruz League. When he returned in 1958, the bonus rule was gone. “Billy Martin showed me how to make the double play in spring training,” he recalled. Boros then went down to the minors.

His progress through Detroit’s system was uneven. In 1958, he started with the Class AA Birmingham (Alabama) Barons, had a cup of coffee with the Class AAA Charleston (West Virginia) Senators, then played over half the season with the Class A Augusta (Georgia) Tigers. After six September games with Detroit, he gathered his passport and went to Nicaragua for more winter ball.

“For a young man who has been in baseball less than two seasons, Boros has done a lot of traveling,” the Detroit Free Press said. “He already has played for seven different clubs—including the Tigers, three of their farms, two teams in Mexico and one in Nicaragua.”5 Boros spent 1959 back in Birmingham, hitting .305, as Birmingham finished first in the standings before falling to Mobile in the postseason best-of-seven Southern Association playoff series. Afterward he went through Army basic training in South Carolina. Finishing in time for 1960 spring training, he would serve six years in the U.S. Army Reserve.

The new season saw Boros with the Denver Bears, the Tigers’ new AAA club. His .317 batting average, 119 runs batted in, and 30 home runs for the pennant winner earned him the American Association’s Most Valuable Player award. “On his way to the Tigers, Steve did everything but climb Pikes Peak for Denver,” Parade magazine said.6

The third baseman got off to an impressive start with Detroit in 1961, hitting above .340 in late May before his average began to slide. “Everything was coming pretty easily,” he said. “And then we went around the league the second time.”7 Boros was also unlucky, hospitalized overnight after a beaning by Eli Grba of the Los Angeles Angels. Two weeks later, on July 23, he broke a collarbone colliding with pitcher Frank Lary on a bunt play, missing over a month.

While with Detroit, Boros struck up a lifelong friendship with Tigers broadcaster Harwell, 18 years his senior. He got along with his teammates as well, despite a growing reputation as a bookworm. “The guys are pretty nice about it,” he said. “They know I’m serious and the kidding is good-natured.” (“Atta boy, Steve,” pitcher Paul Foytack yelled after a good play at third base. “Just for that I’ll buy you a book.”)8

According to the Associated Press, Boros was headed for the Rookie of the Year award before his injuries. “Still, he had a banner year.”9 He hit .270 with 62 RBIs over 116 games but was embarrassed by swatting only five homers. “This young man’s attitude is so appealing that you find yourself pulling for him,” Detroit Free Press sportswriter Joe Falls wrote the next spring. “But it looks like it’s always going to be a struggle for him. The plays in the field come hard . . . handling a good fast ball even harder.”10

Boros stayed with Detroit throughout 1962. On August 6, versus the Indians in Cleveland, he became the ninth Tiger to slam three homers in a game. Sam McDowell gave up a pair, Frank Funk the third, but the visitors lost in the ninth. “Every time I hit one, we lose,” Boros lamented. “That takes all the fun out of it. . . . In six games this year, we lost when I hit one out of the park.”11

Despite 16 homers, Boros had a down year, finishing with a .228 batting average. The Tigers made a 17-game tour of Japan following the season, during which he hit another homer and a key triple. Once home, however, the club quietly traded him to the Chicago Cubs in a straight-up deal for pitcher Bob Anderson.

Since they already had Ron Santo at third, the Cubs planned to use Boros at shortstop, second base, and in the outfield. But a future Hall of Famer stood in his way at every turn. In 41 appearances during 1963, the ex-Tiger played 14 games at first base behind Ernie Banks, 11 in right behind Lou Brock, and pinch-hit 18 times.

The Cubs sold their versatile but light-hitting utilityman in December for an undisclosed sum to the San Diego Padres, Cincinnati’s AAA affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. “The Reds see in him quite a handyman as an infielder-outfielder,” the Cincinnati Enquirer said.12 Manager Fred Hutchinson sent Boros back to San Diego to start the 1964 season, but, as promised, recalled him in May after a strong start.

“Sure hope I don’t let Hutch down,” Boros said.13 He didn’t, promptly reeling off 50 straight errorless games at third base, eclipsing Heinie Groh’s 1920 club record of 47. “I used to try to be a graceful third baseman,” Boros said. “But now I’m a scrambler; more aggressive than I was before.” The reason for the change? “Watching Ron Santo play third. He’s aggressive and I think he’s the best third baseman I’ve ever seen play.”14

That summer he gave a newspaper interview that was pure Boros, almost impossible to imagine from any other ballplayer. He spoke about a play he had written for a creative writing class over the winter. The plot, he said, was inspired by the real case of a young man who had refused an American Legion scholarship because he disliked the group’s philosophy. “I also suggest that the boy might be homosexual,” Boros said, “that he knows it, but as long as he doesn’t harm anyone, so what?”15

In late July, coach Dick Sisler took over the Reds from ailing manager Hutchinson. Cincinnati went on to finish a game behind St. Louis for the National League flag. “Steve Boros did a workmanlike job at the hot corner last season. … But Sisler would like to get more power out of his ’65 third baseman,” Enquirer sports editor Lou Smith reported.

Boros was overseas again in January, but not to play baseball. He stood among 40,000 mourners filing by the flag-draped bier of Sir Winston Churchill at Westminster Hall, London. “During the war I was only a kid squashing tin cans for the war effort,” he said. “But I think everybody realizes the great contribution this man has made.”16

Back home again, Boros played in only two games without a plate appearance before Cincinnati sent him back to San Diego in 1965. “The only surprise was that no major league club was interested in picking up nice guy Steve on waivers,” Smith wrote. “He certainly is better than several third basemen on major league rosters today.”17

Boros never returned to the majors as a player. “They say the average big-league career lasts four and three-quarter years; that’s exactly what mine totaled,” he said years later. “They say the average batting average is .245; mine was exactly .245. I can honestly say I was the average major league player.”18

He played ball for five more seasons in AAA: San Diego, 1965; Buffalo Bisons, 1966-67; Indianapolis Indians and Vancouver Mounties (where his teammates included future managers Tony La Russa and Rene Lachemann), 1968; and Omaha Royals, 1969.

At Omaha, the Kansas City Royals’ affiliate in the American Association, he began a transition into coaching under manager Jack McKeon. Boros had resisted making the shift in Indianapolis. But he’d worked as a substitute teacher and sold women’s shoes and men’s clothing during the off seasons to make ends meet and didn’t care for a life outside of baseball. Since McKeon didn’t need a 32-year-old infielder who expected to play every day, Boros’s choice was simple.

“He explained my role—play part time and help with the younger guys,” the veteran said. Boros did as McKeon asked, while also hitting .272 in 103 games. “Jack thought I did a good job helping with the young players. He took me to the [Florida] instructional league as a coach.”19

The following year, Kansas City made Boros manager of the 1970 Waterloo (Iowa) Royals in the Class A Midwest League. He led the club for three seasons, earning the Ewing M. Kauffman Award in 1972 as the organization’s top minor-league skipper. In February 1973, he married flight attendant Sharla Sisson, the daughter of a Royals’ minor league employee.

Boros next managed the 1973-74 San Jose Bees, the Royals’ Class A California League club. During the off seasons he also skippered Arecibo in the Puerto Rican Winter League. The 1974 Bees ran so often during their 140-game schedule that they became known as the “track show.”20 Their record of 372 stolen bases was “the best in organized baseball since Des Moines pilfered 389 in the Western League in 1906.”21

The Royals called Boros back up to the majors in 1975 as third base coach for manager Whitey Herzog. He shifted over to first base for the next four seasons. One day Herzog told him to clock leadoff man Willie Wilson’s time on the base paths. Boros did and became a stopwatch and statistics fanatic as the club won three AL West titles. But when KC fired Herzog after the 1979 season, the same broom swept out Boros.

He took a big pay cut the next season to manage the Calgary Expos, Montreal’s Rookie League club in the Pioneer League. He enjoyed it. “This is the first time I’m managing an all-rookie team and I’m having fun teaching,” he said. “That’s what I really like to do.”22 Boros moved up to the big club in 1981, again as a first base coach. Montreal president and general manager John McHale had been GM at Detroit when Boros signed there.

Boros used his stopwatch to help rookie Tim Raines become the National League’s top base stealer. “Steve is constantly coming up with things that I didn’t notice or realize, … he changed my start and taught me how much goes into base stealing,” Raines said later.23 Peter Gammons called Boros “Lee Strasberg to Raines and the host of young speedsters coming through the Expos organization.”24

The base-stealing guru coached for two seasons in Canada. In November 1982, Boros was again managing Arecibo, “sending out the message I wanted the chance at a big-league job.” 25 The tactic worked—the Oakland A’s called to interview him about replacing fired Billy Martin, ironically his father’s favorite manager. Once hired, Boros mused aloud about his long path to a major-league manager’s job.

“But so many good people were pulling for me, men like Whitey Herzog, John McHale and Jack McKeon,” he said. “That kept me going,”26 Among his new players was pitcher Matt Keough, son of former Reds teammate Marty Keough.

At Oakland, Boros upgraded from a stopwatch to an Apple computer linked to a mainframe. The skipper “makes final decisions himself, but has the Apple II+ and its sophisticated software available to him,” a tech magazine explained. “Boros says the Apple is particularly valuable for scouting new players. The system gives him data instantly that would take years to accumulate by hand.”27 White Sox manager Tony La Russa, his friend since Vancouver, got impressive results using the same system.

Publications ranging from Sport to Psychology Today ran pieces on Boros’s computers, as if R2-D2 were sitting beside him on the bench. Baseball’s traditionalists didn’t share his enthusiasm. “I don’t need that stuff,” Martin said, pointing to his head. “I’ve got it all up here.”28

Oakland’s players were never quite comfortable with their manager. Despite his success with Raines, for example, Boros was never close to young Rickey Henderson. The A’s entered September in third place in the AL West, five games below .500. But with injuries and a late collapse, they ended at 74-88—disappointing, but six games ahead of 1982. La Russa’s White Sox were the only club in the division with a winning record.

Boros knew he was running out of time in 1984. “Oakland players began to resent Boros’s reliance on the [digital] information, taking him as a cold tactician who ignored the emotional side of the game,” author Alan Schwarz writes. “After A’s center fielder Dwayne Murphy was thrown out in a rundown between second and third, he grumbled to his manager, ‘The computer made me do it.’”29

The A’s dropped eight of nine games during a May road trip. “Billy Martin and Earl Weaver raised the roof. Steve Boros hardly raises his voice,” columnist Art Spander wrote in the San Francisco Examiner. “He’s Emily Post in double-knits and spikes.”30 Oakland’s record stood at 20-24 when the club dismissed Boros the next day. Sportswriters across the country lamented the firing, perhaps feeling they had more in common with the mild-mannered ex-skipper than with the ballplayers they covered.

“Steve Boros was a different presence in a big-league manager’s office, well-read, a gentle person. When he would come to New York, he would get more pleasure in taking in a Broadway play than frequenting the local watering holes,” Joe Donnelly recalled in Newsday.31 Spander wrote from the opposite coast that Boros “read Gandhi and Scott Fitzgerald and kept more diaries than Samuel Pepys. Yet the attributes became secondary to the ball-club’s liabilities.”32

First base coach Jackie Moore took over the A’s. Boros turned down a front-office job, took some time off, and did some writing—he’d been sweating over a novel and a baseball autobiography for years. Later he did some scouting during the last weeks of the season for the San Diego Padres, who went on to play the Tigers in the 1984 World Series. The Padres then hired him as coordinator of instruction for their minor-league staff for 1985.

A year later, Boros took over the team from Dick Williams, who quit suddenly on the first day of spring training. “I was there, and I had experience as a major-league manager,” Boros said.33 He was glad for the opportunity to work again with general manager “Trader Jack” McKeon. His laidback style seemed to resonate with the Padres during camp. “Perhaps,” he said, “I was managing the wrong club before.”34

Boros only had charge of another team in turmoil. The 1986 script turned eerily familiar to 1983’s: “Players thought he was too nice and that he made too many moves.”35 The season ended exactly the same way, too, with his club finishing 74-88.

The Padres let Boros go at the end of the season, replacing him with Larry Bowa. He took his dismissal calmly and left for a vacation cruise in Tahiti with his family. In their isolation, he missed the 1986 World Series entirely. (“Buckner did what?”)36 Boros had no ambition ever to run another club. “The managing didn’t work out,” he said, “but I had to try it.”37

He remained with the Padres as coordinator of minor-league instruction. Boros hoped eventually to succeed McKeon as GM but got a pink slip after one season when Bowa added several of his own men to the staff. The Los Angeles Dodgers then hired him as a special assignment scout, which was ideal. “I really feel at this point of my life, especially my family life, I have the perfect job,” he said.38

After their famously improbable regular season, the Dodgers prepared for the 1988 World Series versus Oakland. Boros, Mel Didier, and Jerry Stephenson scouted the A’s, now managed by La Russa. The trio spotted closer Dennis Eckersley’s tendency to throw a back door slider with a full count on a left-handed batter. Boros sat in Dodger Stadium watching Game One with his family when hobbled pinch-hitter Kirk Gibson hit that very pitch for his impossible walk-off homer. “This is going to go down in history,” Boros said when the ball went out.39

The Dodgers named him assistant minor-league field coordinator for 1990. He stayed with the club until 1993, when he returned to the field in Kansas City as third base coach for Hal McRae. That stint ended in late 1994 when the club fired McRae and his staff. “If this had happened 20 years ago I’d be upset and bitter,” Boros said, “but I’ve been down this road before.”40

He signed with Baltimore as the Orioles’ third base coach in 1995 for manager Phil Regan, an old Detroit and winter ball teammate. “His enthusiasm is what attracted me to him,” Regan said. “I know that he’s totally dedicated to baseball.”41 Boros was praised for his work but was out again when Baltimore cleaned house after the season.

In 1996, Boros’s alma mater inducted him into the University of Michigan Hall of Honor. He finished his baseball career with nine more years at Detroit, as minor-league field coordinator (1996–2002), director of player development (2003), and special assistant to the general manager (2004). During a 47-year career, Ernie Harwell wrote, Boros “displayed knowledge few in the game could match. … I always felt Steve never had a real chance to show what a great manager he might have been.”42

Three years later, Harwell wrote that the ex-A’s and Padres skipper was battling multiple myeloma. “Boros has hundreds of friends in the game,” he noted, “and all are rooting for him in his battle against cancer.”43 Both men died in 2010, Harwell on May 4, his longtime friend on December 29. Obituaries prominently mentioned Boros’s role in Gibson’s historic 1988 homer.

Stephen Boros Jr. died at Deland, Florida, and was buried at nearby Lake Mary. He was survived by his widow, Sharla; daughter Sasha, a university tennis coach; son Steve, an MLB scout; and his daughter from an earlier relationship, Dr. Renee Robinette Ha, a specialist in animal behavior. Ever meticulous, Boros had never quite been satisfied with his novel or autobiography. As of 2021, both were unpublished.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by James Forr.

Sources

Besides the sources listed in the Notes, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Baseball Biography Project proved helpful.

Notes

1 Ernie Harwell, “Ex-Tiger Boros Has Tough Foe in Cancer,” Detroit Free Press, September 3, 2007: 48.

2 “Detroit’s Boros Credits College for Confidence,” Hammond (Indian) Times, May 26, 1961: D6.

3 “Bengals’ Bonus Lands Boros, Third Star from Michigan U.,” The Sporting News, June 26, 1957: 25.

4 Hal Middlesworth, “Tigers Offer Scholarships,” Detroit Free Press, January 22, 1958: 21.

5 Hal Middlesworth, “Tigers Tame After Boros’ Baseball Safari,” Detroit Free Press, February 18, 1959: 21.

6 John Devaney, “Big Leaguers of Tomorrow,” Detroit Free Press Parade, October 9, 1960: 39.

7 Joe Falls, “Boros Has ‘Pull’ At Third Base,” Detroit Free Press, March 3, 1962: 13.

8 Reichler, “Detroit’s Steve Boros.”

9 Joe Reichler, “Detroit’s Steve Boros Hopes to Be Literature Professor,” Greenwood (South Carolina) Index-Journal, March 30, 1962: 6

10 Joe Falls, “Sighting in on Tigers,” Detroit Free Press, March 25, 1962: 2-D.

11 “‘Every Time I Clout Homer, Tigers Lose,’ Boros Moans,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1962: 10.

12 “Reds’ Scrapbook: Steve Boros,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 9, 1964: 42.

13 Lou Smith, “Hutch Keeps His Word to Boros,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 13, 1964: 27.

14 Al Heim, “Steve Boros—Athlete, Scholar,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 4, 1964: 15.

15 Larry Merchant, “Color This Red Different,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 10, 1964: 54.

16 “Reds’ Player Joins Thousands Paying Homage to Churchill,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 28, 1965: 13.

17 Lou Smith, “Boros, Helms Feel Sting as Pruning Ax Descends,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 12, 1965: 29.

18 Joseph Durso, “A’s Dugout: From Acerbic to Cerebral,” New York Times, December 8, 1982: B9.

19 Sid Bordman, “Boros Works His Back to Majors,” Kansas City Star, April 3, 1975: 19.

20 Bordman, “Boros Works.”

21 “Royals Try Again Tonight,” Kansas City Star, September 4, 1974: 1B.

22 Milton Richmond, “Boros Loves Teaching Young Rookie Players,” St. George (Utah) Spectrum, July 1, 1980: 8.

23 Peter Gammons, On Baseball, Boston Globe, February 27, 1982: 28.

24 Gammons, On Baseball.

25 John Brockmann, “Boros Doesn’t Want Another Shot at Majors, Thank You,” Des Moines Register, July 18, 1988: 2D.

26 “Boros: Perseverance Key to Reaching Bigs,” Lafayette (Indiana) Journal and Courier, November 18, 1982: D7.

27 Frank Harrison, “A is for Apple, Oakland, and Baseball,” A+ Magazine, November 1983: 58.

28 Ray Kennedy, “It’s the Apple of His Eye,” Sports Illustrated, June 6, 1983: 72.

29 Alan Schwarz, The Numbers Game: Baseball’s Lifelong Fascination with Statistics, 146.

30 Art Spander, “A Civilized Approach,” San Francisco Examiner, May 23, 1984: F-1.

31 Joe Donnelly, “In Baseball Nice Guys Don’t Last,” New York Newsday, May 26, 1984: 30.

32 Art Spander, “Boros Firing: The Bottom Line Rules,” San Francisco Examiner, May 25, 1984: F-1.

33 Brockmann, “Boros Doesn’t Want.”

34 Friend, “Boros Finally Has a Job”

35 Tom Friend, “Boros Back and His Mood is Sunny,” Los Angeles Times, November 3: III-12.

36 Friend, “Boros Back.”

37 “Orioles’ Boros Hasn’t Lost His Zest for Game,” Easton (Maryland) Star-Democrat, March 9, 1995: B1.

38 Brockmann, “Boros Doesn’t Want.”

39 Brandon Foster, “Missouri Tennis Coach Sasha Schmid Furthers Father’s Coaching Tradition,” Columbia Missourian, April 15, 2015: https://www.columbiamissourian.com/.

40 “McRae’s Staff Dismissed, Too,” Kansas City Star, September 16, 1994: D-5.

41 “Orioles’ Boros Hasn’t Lost.”

42 Ernie Harwell, “Boros Served Tigers Well in Many Roles,” Detroit Free Press, September 20, 2004: 2G.

43 Harwell, “Ex-Tiger Boros.”

Full Name

Stephen Boros

Born

September 3, 1936 at Flint, MI (USA)

Died

December 29, 2010 at Deland, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.