Tom Hufford: Memories of Cooperstown and the Founding of SABR in 1971

This article was originally published in the Magnolia (Georgia) Chapter’s Spring 2025 newsletter.

In 2006, SABR founding members Tom Hufford, Cliff Kachline, and John Pardon gathered in Cooperstown to celebrate the organization’s 35th anniversary. The plaque honors SABR’s first organizational meeting at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown on August 10, 1971.

The SABR story has been told before, but often not in great detail. A history of SABR was published in 2000 by Turner Publishing, but while the book did contain a somewhat abbreviated discussion of the history of the organization, it consisted mostly of self-submitted biographies of members. The late SABR member Dick Thompson compiled a more comprehensive history in the early 2000s, and I updated that manuscript about 20 years ago. That history can now be found on the SABR website, and it is basically an overview with names, dates, facts, and figures, but few behind-the-scenes stories.

So, what I will do here is to use the first part of the SABR history that I updated about 20 years ago, and add some commentary, recollections, and impressions of that inaugural SABR meeting back in 1971.

Some of what you will read will be copies of the letters Bob Davids wrote detailing his interest in forming the Society and what he was thinking, with my commentary added. — TH

Baseball is in the fiber of America. As long as there have been baseball fans there have been baseball fanatics, those of us who search for a deeper understanding of the game. On August 10, 1971, 16 such fanatics met at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York, to form the Society for American Baseball Research.

The baseball establishment ignored the Society when it was formed 54 years ago. Today, as membership tops 7,400, the profession of baseball and the various media that report the game are well aware of the collective knowledge and expertise of our group.

Mr. Bob Davids

The logical place to begin a history of the organization is with its founder, L. Robert “Bob” Davids. Bob’s dedication and contributions to both the Society and baseball have been evident for all to see.

In 1985, Bill James wrote that Davids “has done more for baseball research than anyone else living.” In 1994, the National Baseball Library and Archive at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown named a study room in his honor.

Bob was born in Kanawha, Iowa, on March 19, 1926. Following military service in World War II, Bob enrolled at the University of Missouri where he received a degree in journalism in 1949 and a master’s degree in history in 1951. After moving to Washington, DC, he began a 30-year career with the United States Government, working at the Pentagon and the Atomic Energy Commission. He received a Ph.D. in international relations from Georgetown University in 1961.

Bob had been a freelance contributor to The Sporting News since 1951. His first article, on Ralph Kiner, earned him $7.50.

My baseball history, before SABR

I was a baseball fan and like many boys my age I collected baseball cards. I started collecting in earnest in 1961, when I was 11, and a couple of friends and I each tried to put together a complete set of Topps cards that year. None of us were successful, since the seventh and last series of the set never made the candy shelves in our small town, Pulaski, Virginia.

I knew very little about baseball history as a teenager. Every few weeks, on Saturdays, my father would take me to downtown Pulaski to the Elks Club barber shop to get a haircut. There would always seem to be the same old gentleman sitting in the corner making conversation and talking baseball.

One time, my father said the gentleman was Doc Ayers. “He pitched for the Washington Senators forty or fifty years ago,” my father said. “A spitball pitcher. Walter Johnson would pitch one day, and Doc would go out the next.” I knew the Washington Senators name from my baseball cards, but I knew none of the guys they talked about at the barber shop.

My father knew Doc and introduced me to him one day as I showed more interest and paid more attention. So, Doc Ayers was the first Major Leaguer I ever met.

I became aware of The Sporting News when I saw it on the magazine rack at our local Walgreens about 1963. I started buying it and I read it from cover to cover. I became fascinated by a semi-regular column that Lee Allen would write.

Lee was the Official Historian at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and his column appropriately enough was called “Cooperstown Corner.” His articles ran the gamut of every possible baseball topic, but the ones I liked best were the ones that he would write as spring training was ending. He would write about the old, long-forgotten ballplayers that he would stop and visit during his drives back to Cooperstown. I remember one of Lee’s articles about finding an old catcher from the 1920s-30s period, Roy Spencer. Lee had been looking for Spencer for a number of years and finally found him, down on his luck, living on a houseboat at a dock in Florida.

His story was interesting, and I thought it sounded like Mr. Spencer could use some help. So I wrote him a letter, asked for his autograph and enclosed a few dollars. I addressed it simply as “Mr. Roy Spencer – Houseboat – Port Charlotte, FL.” A letter addressed like that now probably wouldn’t be delivered – but it was then, and I still have Mr. Spencer’s reply.

Lee Allen’s focus was to complete biographical information of every Major League player, and that seemed like a worthwhile endeavor to me, too.

The Good Book(s)

It was while I was in high school that I discovered a copy of The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball by Hy Turkin and S.C. Thompson, at the local library. The book had been published in the 1950s and really had only minimal statistics and scant biographical data on the players, but it did have listings of every player to have played in the Major Leagues.

I spent countless hours going through that book and making a list of every player who had a birth or death place in Virginia, then adding West Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Washington, DC.

I was struck by how many players were simply listed with a birth state, but no town and no birth date, or who were listed just by their last name. These were players who had made the Major Leagues, after all, and like Lee Allen, I was puzzled that complete information wasn’t available for each and every one.

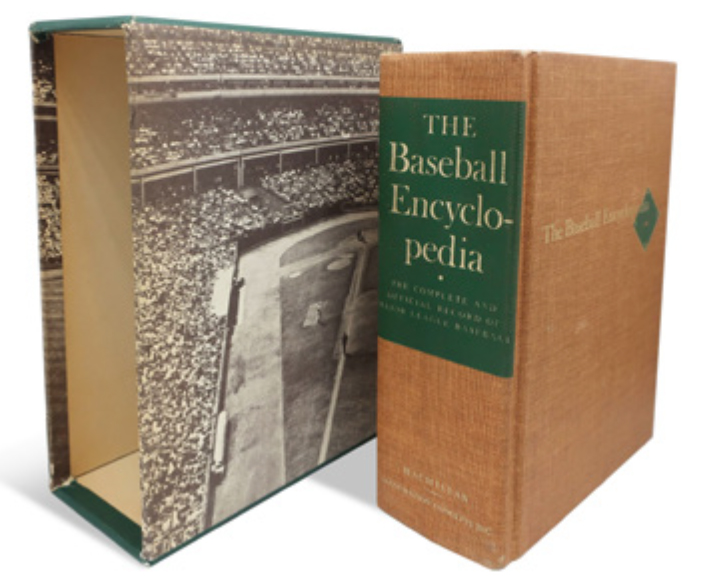

Two significant events happened in baseball in 1969. One was that the New York Mets won the World Series, and the other was the publication of The Baseball Encyclopedia by The Macmillan Company. This massive volume was the first baseball encyclopedia to have been produced using a computer, and it included complete playing records for every Major League player.

It also included greatly expanded player biographical data: dates and places of birth and death, complete names, heights, weights, bats/throws. This was the data had been compiled over the years by Lee Allen. The publication provided the most complete record to date of the then almost 10,000 former Major League players.

A quick review of the book, though, showed that there were several thousand players whose complete names had never been recorded, whose deaths had been overlooked by local newspapers or never reported to the baseball community, or for whom other information was lacking. There was still a lot of work to be done.

BioProjects

The Macmillan encyclopedia did give me information to update my “players by states” lists, and I began trying to fill in some of the missing information for Virginia-born players. Some players were relatively easy to track down, but others would take many years to find.

Armed with the out-of-town telephone directory collection and newspaper microfilm resources at the Virginia Tech library, it wasn’t long, though, before I had located dozens of living former big-leaguers, and the relatives of numerous others, who were only too happy to fill in missing data.

Not knowing exactly what to do with the new player biographical data that I was uncovering, I contacted Clifford Kachline, who had taken over the job of Historian at the Baseball Hall of Fame, after Lee Allen’s death.

Cliff had just completed a 30-year stint on the staff of The Sporting News and was delighted to receive the new data I had found. Cliff sent me a supply of the biographical questionnaires that the Hall of Fame used, and I then used those when contacting players or relatives for information.

He also put me in touch with several other researchers across the country, who shared my same interest in baseball history, more specifically the biographical information on the players. Most notably among these researchers were Joe Simenic from Cleveland, Bill Haber from Brooklyn, and Bill Gustafson from San Jose.

We corresponded with each other, in effect we had our own little research club, and traded information back and forth about what we were each doing. No internet in those days and very few phone calls. Just lots and lots of letter writing. And when we would crack a case and find a particular player, we would then send that data to Cliff Kachline in Cooperstown.

Letter #1

As far as SABR was concerned, the organization began to take shape with Bob Davids’ March 19, 1971, letter (and I just noticed that it was dated on his birthday – Bob liked to do things like that!) It read, in part, as follows:

- This letter is being addressed to about 25-30 persons interested in baseball history and statistical research (I use the term “statistorians”). You are an addressee because I have seen your name in The Sporting News in past years appended to an interesting historical or statistical article, or your name has been passed on to me by Ray Nemec, Bob McConnell, Leonard Gettleson, or Cliff Kachline.

- There may be many more than 25 or 30 baseball statistorians around the country. We don’t really know, but I thought some effort should be made to organize this “motley crew” into a more formal group. For that reason we plan to hold an organizational meeting at Cooperstown, New York on August 10-11, 1971. Cliff Kachline, Hall of Fame Historian, has kindly invited us to meet in the museum library. The Hall of Fame baseball game and induction ceremonies will be held on Monday, August 9.

- Why don’t we meet then on August 7-8? Impossible, says Cliff. The place is busier than Washington on Inauguration Day. You could come on August 9, take in the induction festivities and get a motel room for the night, but not before, and then be available for meetings the next day.

- What would be accomplished at the Cooperstown meeting? From general to specific, your attendance would provide an opportunity (1) to see Cooperstown and the always changing Hall of Fame Museum; (2) to meet and exchange firsthand views with other statistorians; (3) to review specific areas of baseball interest to avoid duplication of effort; (4) to establish an informal group primarily for exchange of information; or (5) to establish a formal organization with officers, dues, a charter, annual meetings, etc.; (6) to consider the establishment of a publication in which our research efforts could be presented; and (7) to take up additional matters which you may suggest in response to

this letter. - What do you do now? You should send me a note saying something along the lines of (1) Your idea of a get-together of the baseball statistorians sounds great, I would like to attend; (2) I am interested in your efforts to organize this group, I would like to be included but cannot get away for a meeting at Cooperstown this summer; or (3) your plans for an organization are completely impossible; take me off your mailing list, quick.

- I would also hope that you would include in your response the name of additional baseball “nuts” who might qualify or be interested. The next step would then be for me to send to those of you who could make this meeting this summer the information of hotels and motels which you would need for the night(s) of August 9 and 10; August 10 only; or August 10 and 11, depending on your travel plans.

I was excited to receive this letter. I didn’t know anything about Bob Davids except for his by-line on baseball historical articles in The Sporting News from time to time. I had corresponded quite a bit with Cliff Kachline, but I wasn’t familiar with any of the other people mentioned in the letter. I assumed that Cliff had given Bob my name, but I asked myself what I could possibly add to a group such as the one being proposed?

I was intrigued, though. I was a big baseball fan, but I had never been to Cooperstown, and the meeting would be held two days after that year’s Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. Of the eight players being inducted that year, Satchel Paige would be the big attraction. Perhaps I would have a chance to meet him – but if not, there should be plenty of other former stars around, certainly I should be able to talk to someone or get an autograph or two. I had no idea how that meeting would change my life.

Letter #2

Bob mailed a second letter on April 16. The important excerpts are as follows:

- Although I still haven’t heard from several addressees, I thought I should not wait any longer to get out report No. 2 to those who did respond. Let me say first that my initial mailing of 32 letters brought back 20 replies and three envelopes with “address unknown” stamped on them. Of those 20, there were 17 who expressed interest in the idea of an organization and a desire to be part of it; three expressed mild indifference. Eleven said they plan to go to Cooperstown. Several of you suggested additional researchers and I sent off 10 more letters.

- Most of you responding stated your interest in an organization publication where in you could present some of your research results. This sounds feasible. Several mentioned interest in firsthand exchange to find out what others are doing. I was surprised at the range of specific interests: baseball photos, baseball parks, birthplaces, home runs, etc. Some of you said you had specific ideas of what should be taken up at the proposed meeting. Now is the time to come forward with these ideas so I can prepare a draft agenda.

- Be completely candid in your suggestions, for nothing is frozen in place at this point except the date, August 10.

Still questioning whether or not I should go to Cooperstown, I finally decided that even though I might not have anything to add to the group, the thought of visiting the Hall of Fame was an opportunity that might not come again. I decided to phone Bob Davids and talk with him about the proposed trip, and right away Bob said, “If you can get to Washington, you can ride up with my family and me.”

So, when August rolled around, I caught a bus from Pulaski to Washington and set upon my Cooperstown adventure.

I don’t remember the exact date of my arrival in Washington, just that I walked several blocks from the downtown bus station to the old Ambassador Hotel at the corner of 14th and K Streets, where I spent the night. Or maybe it was two nights.

It also just so happened that the Washington Senators were playing at home that week and Bob picked me up to go to the game at Robert F. Kennedy Stadium. It was the first and only game I ever saw at RFK, and I remember nothing about it. By looking at Baseball-Reference, I see that the Cleveland Indians played four games at Washington on Thursday, August 5, through Sunday, August 8. I know it wasn’t August 8 because we were in Cooperstown that day, and we probably drove on Saturday, so we either saw the Nats’ 7-1 loss on Thursday or their 7-3 win on Friday.

Either way, we didn’t know it at the time, but the Senators would only call RFK home for less than two more months, before moving to Texas for the 1972 season. And some day I’ll learn the exact date of the game we saw, because I’ve never thrown away a ticket stub – I just don’t know where they all are at the moment!

The morning we were to head north, Bob came by the Ambassador Hotel and we drove back to his home in northwest Washington. There we picked up Bob’s wife, Yvonne, and daughter, Roberta, to begin the 375 mile trip to Cooperstown. We traveled north through Pennsylvania and spent the night at a motel somewhere near the Pennsylvania/New York border.

Arriving in Cooperstown

We arrived in Cooperstown in plenty of time to park and to go stand in front of the National Baseball Library, a building connected to the rear of the Hall of Fame, where the induction ceremonies were held. I remember it was a hot August day, so we hunted for a space in the shade. The crowd for the induction ceremonies would be a fraction of what it is in today, but part of the reason may have been that 1971 was an unusual induction year. No players were elected by the Baseball Writers of America group, one player – Satchel Paige – was elected by the newly formed Negro Leagues Committee, and seven players or executives were elected by the Veterans Committee. None were well known – Jake Beckley had died in 1918, and Joe Kelley in 1943, Dave Bancroft and George Weiss were ill and could not attend. Only Veterans Electees Chick Hafey, Harry Hooper, and Rube Marquard were alive and able to attend, and their Major League careers had ended in 1937, 1925, and 1925 respectively. Not exactly household names. Satchel Paige was easily the draw for this year’s ceremonies.

In those days an exhibition game would be played on the same day after the induction, pitting an American League team against a representative from the National League. Our SABR organizational meeting wasn’t scheduled until Tuesday morning, but several of the attendees were already in town, and Cliff Kachline graciously obtained tickets for us to attend the game. This year, the Cleveland Indians bested the Chicago Cubs by a score of 13-5 at Doubleday Field.

After the game, players from both teams mixed and mingled with the fans in the parking lot, before they boarded their buses for the trip to the airport. That’s where I met Ernie Banks and got his autograph.

Participants at SABR’s organizational meeting on August 10, 1971, at the National Baseball Library in Cooperstown, New York. Back row, from left: Neil Campbell (visitor), Bill Haber, Keith Sutton, Dan Dischley, Dan Ginsburg, Tom Hufford, Ray Nemec; front row: Cliff Kachline, Ray Gonzalez, Bill Gustafson, Joe Simenic, Paul Frisz, Tom Shea, Bob McConnell, John Pardon, Bob Davids. (Pat McDonough is the only founding member not pictured above.)

The Big Meeting

After the induction ceremonies were completed, the Hall of Fame game was over, and the Village of Cooperstown got back to normal, a meeting was held at the National Baseball Library, a part of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. The date was Tuesday, August 10, 1971, and of the several dozen people who had received invitations to attend from Bob Davids, 17 attended. No, that is not a misprint. The group is called the Cooperstown 16 now, but 17 actually attended. Neil Campbell happened to be in the library that day, attended the meeting, but ended up never joining the group.

I was one of those persons who attended, and who spent the day talking about our interests in researching and preserving baseball history. The group came from as far away as San Jose, ranged in age from 15 to 75, and represented diverse baseball interests such as biographical research, statistical analysis, home runs, minor league history, 19th century baseball, research on triple plays, book collecting, etc., etc. One photo was taken of the group during the meeting. Visitor Neil Campbell is in the photo, but member Pat McDonough isn’t. Pat must have taken the photo!

The first part of the meeting consisted of each of us introducing ourselves to each other. It struck me as odd that of all the attendees there, few had ever met any of the others. Many had corresponded with each other over the years, but everything seemed to have been done by mail, with very few phone calls ever involved.

I also noticed how young I was compared to most everyone else. But I wasn’t the youngest in attendance. That honor went to Dan Ginsburg, 15, from Pittsburgh. His dad brought him and everyone thought the elder Ginsburg was there for the meeting, but no, Mr. Ginsburg dropped off Dan and left to go see the sights of Cooperstown. It turned out that Dan, at his tender age, had done significant research on the Pittsburgh teams of the 1890s. He later wrote a book entitled The Fix Is In: A History of Baseball Gambling and Game Fixing Scandals (1995).

Unfortunately, in addition to being the youngest SABR founding member he was also the youngest to die, at the age of 53, a week after attending the 2009 SABR convention in Washington, DC.

At age 21, I was the second youngest in attendance that day, followed by Dan Dischley at 27, Bill Haber at 29, and John Pardon at 33. All the rest seemed to be much older, but I reckoned that they had to be, since they already knew absolutely everything there was to know about baseball. But now as I look back, I see that our oldest founder was 67 and I’m now 75 — and I am amazed at how much I don’t know about baseball!

Once the business meeting actually started it moved along very quickly, a credit to the work Bob Davids had done in making out an agenda, and building on responses to the invitations he had previously mailed out.

There was general consensus among those gathered that it would be beneficial to organize a formal group. Bob Davids asked Cliff Kachline, who had regular contact with many researchers and writers across the country, how many people he thought might ultimately be interested in such a group, and after giving it some thought Cliff responded that there might be a total of “about 50.”

After much discussion, the group defined the following five objectives:

- To foster the study of baseball as a significant American social and athletic institution.

- To establish an accurate account of baseball through the years.

- To facilitate the dissemination of baseball research information.

- To stimulate the best interests of baseball as our national pastime.

- To cooperate in safeguarding the proprietary interests of individual research efforts of members of the Society.

The group also established four active committees. They were Biographical Research, Publications, Minor Leagues, and Negro Leagues. The possibility of having a Baseball Records Committee was also discussed, and was added later.

After our lunch, we resumed our discussions and agreed to have annual dues of $10, and made plans to establish a constitution, an annual meeting, and the publication of a newsletter.

What’s in a name?

All of the above was decided upon rather quickly, but agreeing on a name for the group was another matter. It took the rest of the afternoon. Discussion of a name for the organization centered around geographic coverage, a possible acronym, and a means of covering both the historical and statistical aspects of the group without having a long title. It was generally agreed that the word “research” accomplished the latter. In regard to geographic scope, it was stated that “American” was broader than “National,” because that would include North, Central and South America. “Society” was preferred over “Association.” Several proposals regarding a name designation with a baseball acronym were tried, but nothing seemed to work. “Research on Baseball Institute” (RBI) was awkward, and “Baseball Research Association” (BRA) wouldn’t work either.

Finally, Bill Gustafson’s suggestion of “Society for American Baseball Research” and SABR were decided on.

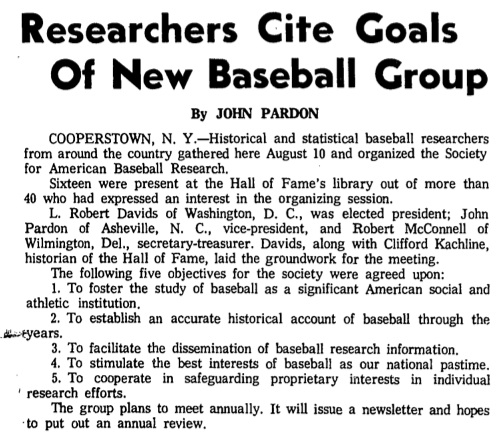

At the end of the meeting, Bob Davids was elected President, John Pardon Vice-President, and Bob McConnell Secretary-Treasurer.

Growth spurt

Shortly after the Cooperstown meeting, The Sporting News ran a small article about the formation of SABR, and it became apparent very quickly that there were more than “about 50” researchers interested in such an organization.

Within a year, membership had reached 100, topped the 300 level in 1975, and hit the 1,000 mark in 1979. Today, SABR is a not-for-profit organization with just over 7,400 members, and SABR has established itself as the oldest and most respected sports research group in the world.

As for me, after that August 10 organizational meeting, Bob, Yvonne, and Roberta Davids returned to Washington, DC, and I stayed behind in Cooperstown for a few days. After all, I hadn’t yet been to the Hall of Fame museum and wanted to spend at least a day exploring the vast resources in the HOF Library, and to have dinner with Cliff and Evelyn Kachline.

I got to do all that, and Cliff pointed me to the local bus system which made a trip every other day to New York City. I enjoyed the ride, walked around NYC for a few hours, then boarded the Greyhound that headed back to Virginia.

I took with me priceless memories that I hope I never forget, and precious friendships within the SABR organization that have lasted over 50 years. I’ve been truly blessed!

The growing need for an organization

At the ceremony to honor the 20th anniversary of the Society on August 10, 1991, Bob Davids outlined the factors and steps that led him to consider starting an organization like SABR:

- The death of J.G. Taylor Spink in 1962 and the subsequent transition of The Sporting News to an all-sports publication which sharply reduced the baseball publishing efforts of several future SABR members.

- Bob’s January 8, 1966 letter to Barnes Publishing Company proposing a baseball book with chapters to be written by Lee Allen, John Tattersall, Keith Sutton, Ray Nemec, Leonard Gettleson, and Bob himself, which Barnes quickly declined.

- Bob’s parallel decisions in January 1971 to publish the Baseball Briefs newsletter and to send letters to Bob McConnell, Ray Nemec, Cliff Kachline, and others proposing the formation of a “Statistorian” type group and asking names and addresses of other interested researchers. Almost all responded favorably and provided other names.

- Cliff Kachline’ s agreement to provide a meeting site at Cooperstown the day after Hall of Fame inductions on August 10, 1971.

- Multiple responses from Baseball Briefs subscribers and new contacts providing a growing mailing list of some 40 persons who were sent invitational/instructional letters on March 19, April 16, and June 28, the final letter containing the meeting agenda.

Reporting on the death of a Black Sox outlaw

In late 1969, I had located former major league first-baseman Arnold “Chick” Gandil, living in California. Gandil was generally regarded as the ring-leader of the eight members of the 1919 Chicago “Black Sox,” who conspired to throw the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. He and the other seven were eventually banned from baseball for life. I didn’t bring that up when I contacted Gandil.

Instead, I mentioned that I lived in Pulaski, Virginia, the same town as Gandil’s 1913-15 Washington Senators teammate Doc Ayers, and that I enjoyed meeting Ayers on numerous afternoons at the Elks Club barber shop, where he would tell stories about his baseball career.

Gandil, who had become a plumber after his baseball days, responded to me, and the two of us exchanged letters for about a year.

In early 1971, I received a letter from Mrs. Gandil, telling me that Chick had passed away the previous December. I forwarded that info along to Hall of Fame historian Cliff Kachline, who mentioned it to a friend at The Sporting News. Gandil’s death hadn’t been reported in the press and The Sporting News ran an article, “Death of Black Sox’ Gandil Goes Unnoticed.”

A few weeks later, TSN sent me a check for $5. No explanation, just a check in an otherwise empty envelope. Cliff said that someone must have been appreciative of my info regarding the Gandils, and that was their thanks. In hindsight, I wish I had never cashed that Sporting News check. It’s the only money I’ve ever received as a result from over 50 years of baseball research!

Several years later I learned that Mrs. Gandil had died within a week or two of contacting me with news of her husband’s passing. I completed my odyssey with Mr. and Mrs. Gandil in 2006, when my wife, Nan, and I were in California and visited their burial site in St. Helena, in the California wine country.

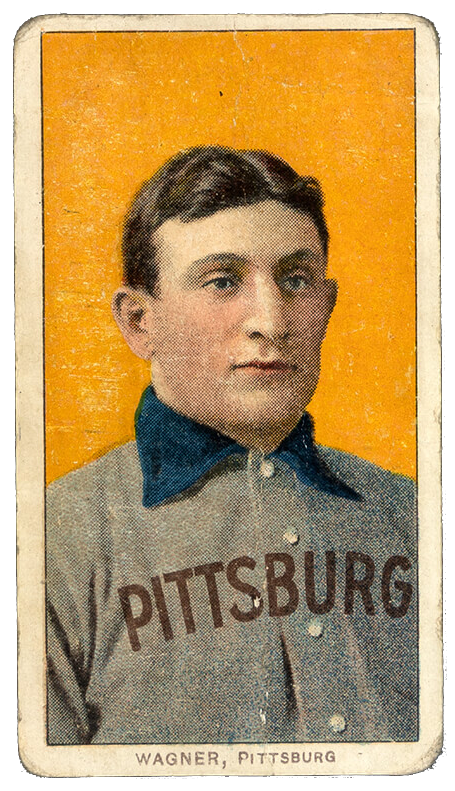

The $500 Wagner card

In Cooperstown, we had accomplished so much so quickly at the first SABR meeting on the morning of August 10th, 1971, we decided we had time to take a lunch break. I think we all walked over to the Short Stop Restaurant on Main Street.

Bill Haber, who worked for the Topps baseball card company, brought along his briefcase for safe-keeping. When he opened it, I had mixed feelings about what I saw. Bill and I were both baseball card collectors with one big difference – he had a job, and I didn’t. We both were interested in older cards, such as the ones he had in his briefcase, cards from the 1910 era.

I first became interested in these cards when I made an acquaintance with Wirt Gammon, longtime sports editor of the Chattanooga Times. Wirt was born in 1905 and collected the cigarette cards as a boy. He was getting older (in his 60s!) and had decided to sell much of his collection. I was trying to buy cards from the set, now known as the T206 set, which included cards of about 525 major and minor league players. Wirt would send me cards on approval, priced at 35 cents each. I told him how many cards to send, and when they came I could take out the ones I needed, and return the rest. All cards were the same price, whether it was Ty Cobb or Nap Rucker, all except for Honus Wagner.

I was aware that the Wagner card from this set was notoriously rare. When I passed the 400-card mark and “only” needed a bit over 100 cards to complete my set (which I knew I would never do), Wirt asked me if I would be interested in purchasing one of his Honus Wagner cards. Interested, yes, but financially speaking, not possible.

Wirt gave me a price, which was more than the total of all the other cards I had bought from him. As I was a college student with at least two more years to go, I politely declined.

So there in Cooperstown, inside the Short Stop, Bill opened his briefcase and did a show-and-tell of his T206 card set.

“I finished this set,” Bill said, “just got the last card that I needed.” When we asked him what that card was, he said “Honus Wagner, it’s a very rare card. I got it from Wirt Gammon in Chattanooga. Had to pay $500 for it!” Well, if I couldn’t have it, I was glad Bill got it. But I knew he had a full-time job, and I didn’t, so I understood.

I got to see that Wagner card one more time. In December 1977 I had to be in New York City on business for a few days. I arranged to visit Bill at his home in Brooklyn one night, and he said “I’m glad you came by, I could use your help.”

I asked what he needed, and he said “I’m working on the 1978 Topps baseball set, and I’m way behind. I still have to do the narrative on the backs of about half the cards. Let me give you a player’s name, you tell me something you know about him, and then we’ll figure out a little blurb to write about him.” So, we worked into the night, wrote the backs to about 250 cards, and I got to see and hold that Wagner card again.

After Bill died, his collection was sold at auction, and I’ve followed that Wagner card through several other auctions. It was sold by a recent owner, who lives in Peachtree City, a couple of years ago for well over $1 million — “to put his kids through college.”

Today I can go into a baseball card shop and pick out the 1978 cards I did the backs for! I still need the Wagner card and three others to complete my T206 set — but I don’t plan to do it.

On the ball at the Otesaga

An autograph collecting friend of mine from Philadelphia who routinely attended the induction ceremonies in Cooperstown had told me that the Hall of Famers usually stayed at the Otesaga Hotel, only several blocks from the Hall, and often these men spent their free time in the hotel lobby after the ceremony. He told me that there might be a chance to meet some of the players by going to the hotel, which would be open to the public.

So in preparing to go to Cooperstown in 1971, I purchased one Major League baseball at a sporting goods store in Virginia and took it along with me. At the Otesaga, I found there were hardly any “outside visitors” there – and by the time the weekend was over, I had the chance to meet and talk with Hall of Famers Frankie Frisch, Lefty Grove, Pie Traynor, Charlie Gehringer, Dizzy Dean, Bill Dickey, Ted Lyons, Joe Cronin, Zach Wheat, Bob Feller, Edd Roush, Sam Rice, Luke Appling, Burleigh Grimes, Casey Stengel, Red Ruffing, Joe Medwick, Stan Coveleski, Waite Hoyt, Stan Musial, Lou Boudreau, Earle Combs, Ford Frick, Jesse Haines, Chick Hafey, Harry Hooper and Rube Marquard.

Marquard, who had pitched in the majors from 1908 until 1925 and was 85 years old in 1971, had a large scrapbook of his career with him. He spent about two hours going through the book with me and recalling his career. Rube and I then exchanged holiday cards until his death in 1980. I cannot imagine something like that happening today!

My one disappointment was that I got to meet almost every baseball notable there in 1971 EXCEPT for Satchel Paige. Cliff Kachline told me later that Satchel wanted to bring so many people with him that there weren’t enough rooms at the Otesaga, so Satchel reserved an entire hotel in a nearby town.

The experience at Cooperstown went beyond my wildest expectations. I had a chance to meet several dozen Hall of Fame players and had my one baseball signed until there was no room for another single signature.

Tom Hufford was honored on the field by the Baltimore Orioles at Camden Yards on August 19, 2022, during SABR’s 50th annual convention.