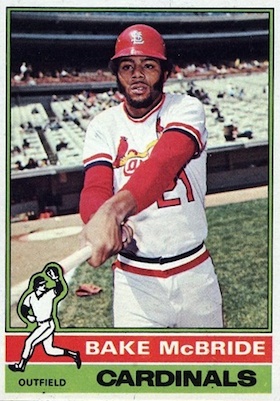

Bake McBride

On October 15, 1946, the St. Louis Cardinals won their sixth world championship with a 4-3 victory over the Boston Red Sox. Enos Slaughter led off the bottom of the eighth inning with a single, and with two outs scored from first base on Harry Walker’s double to left-center field. The play, which later became known as Slaughter’s “Mad Dash,” sent the frenzied Cardinals fans at Sportsman’s Park into a celebratory mood.

On October 15, 1946, the St. Louis Cardinals won their sixth world championship with a 4-3 victory over the Boston Red Sox. Enos Slaughter led off the bottom of the eighth inning with a single, and with two outs scored from first base on Harry Walker’s double to left-center field. The play, which later became known as Slaughter’s “Mad Dash,” sent the frenzied Cardinals fans at Sportsman’s Park into a celebratory mood.

Fast-forward to 28 years later, and another “Mad Dash” became part of the annals of St. Louis Cardinals history. Perhaps the circumstances and the ultimate result were not the same as Slaughter’s, but the label fits all the same. This time it was a Cardinals rookie, Bake McBride, who made the dash.

The Cardinals were facing the New York Mets at Shea Stadium on September 11, 1974. St. Louis was trailing Pittsburgh by 3½ games in the National League’s East Division, and with the season nearing its conclusion, every game was important. The pitching matchup featured St. Louis rookie Bob Forsch (4-4, 2.80 ERA) and the Mets crafty southpaw Jerry Koosman (13-9, 3.30). Neither pitcher would be around for the conclusion of the game.

St. Louis third baseman Ken Reitz tied the game, 3-3, in the top of the ninth inning with a two-out, two-run homer off Koosman. The game was going to extra innings, and how! The Cardinals and Mets played 16 more innings of baseball, and it was not decided until 3:13 A.M. In the top of the 25th inning, McBride led off with an infield single to short. With Reitz at the plate, St. Louis manager Red Schoendienst put on the hit-and-run. McBride had stolen his 24th base of the season earlier in the game. “I was leaning,” said McBride. “Leaning back on my heels, resting.”1 New York reliever Hank Webb fired the baseball to first and had McBride picked off. However, the pitch got past first baseman John Milner and went down the right field line. Off to the races went the speedy McBride.

“When I turned second, I said to myself I am going all the way,” said Bake.2 And he did. He ran through the stop sign by third-base coach Vern Benson. “I didn’t see any sense in sending him home with nobody out,” Benson said.3 McBride, who said he didn’t pick up the stop sign, slid home ahead of Milner’s throw, which catcher Ron Hodges dropped. “Hodges was up away from the plate and I was sliding behind him,” said McBride.4

Sonny Siebert, who had entered the game in the 23rd inning, picked up the win. The game took 7:04 to play. As of 2016 it was still the longest night game ever played in the major leagues. One call that almost went unnoticed was that when Webb made his pickoff throw to first base, second-base umpire Bob Engel called a balk. “Before they revised the rule a few years ago, the runner would have been stopped at second base,” said Engel. “Under that rule McBride might not have scored and they could still be playing the game.”5

Arnold Ray McBride was born to Arnold and Wanna McBride on February 3, 1949, in Fulton, Missouri, about 25 miles northeast of the state capital, Jefferson City. The elder McBride, also known as Bake, pitched in the Negro Leagues with the Kansas City Monarchs, and was a teammate of Satchel Paige. He made his living as a cement worker and bricklayer. His mother, Wanna, worked as a nurse. As for the unique nickname of Bake, its origins seem to be unknown. “They called my father Bake. I didn’t know why. They started to call me Little Bake and it’s been Bake all my life,” said McBride.6

McBride was a three-sport star at Fulton High School. He was an all-state selection as a wide receiver and defensive back in football, and excelled in basketball and track. (The school did not have a baseball program.) Before the basketball season began in his senior year, McBride injured his ankle when he came down on another player’s foot. He thought it was just a sprain, but his mother sent him to see a specialist when the pain intensified. “The bone in the ankle was so badly messed they had to take it out and put in a steel clamp,” said McBride. “The doctors seriously questioned whether I’d be able to walk again.”7

In spite of the setback, the college offers still came in. McBride selected Westminster College in Fulton. He was a standout in track and field, and in 1969 set the school’s record for the 220-yard dash at 20.90 seconds. McBride also played basketball and baseball for coach Harold Flynn. When he tried out for baseball, “He had me pitch and play first base, but when he saw me at first he said ‘Get into the outfield,’” McBride recalled.8

For not having played much organized baseball, McBride showed a high acumen for the sport. His speed and hitting ability were off the charts. But McBride dropped out of Westminster after two years. He was tired of the college life. His father had died when he was 16. McBride’s mother remarried and relocated to Springfield, Illinois. McBride joined her after leaving college. Offered a tryout by the NBA’s Phoenix Suns, he was ready to accept when Flynn told him the Cardinals were holding tryouts at Busch Stadium, and urged him to try out. “I went, but I was scared,” McBride said. “They asked me what position I play and I said, ‘Pitcher.’ They said, ‘Let’s time you running to first base.’ After they clocked me they said, ‘Let’s put you in the outfield.’ I said, ‘Okay, but I can pitch.’ They never gave me a shot at pitching.”9

St. Louis selected McBride in the 37th round of the free-agent draft on June 4, 1970. With the Cardinals rookie team in the Gulf Coast League in 1970, he batted .423 in 17 games before being promoted to Modesto of the California League, where he batted .294 in 26 games. After the season, on December 11, 1970, McBride exchanged “I do’s” with Celeste Woodley, his high-school sweetheart. They had three children.

McBride spent the 1971 season at Modesto, stealing 40 bases. He batted .303 and led the team in runs scored with 85. He continued to climb the ladder in the Cardinals’ minor-league organization. A left-handed batter, McBride hit well on his climb. “I actually like to hit against left-handed pitchers,” he said when the Cardinals brought him up, “because I know I have to watch the ball longer before committing myself at the plate.”10

During the offseason, McBride took courses and eventually graduated from Westminster College with a bachelor’s degree.

He was promoted to Arkansas of the Double-A Texas League in 1972. By midseason the Travelers skipper, Fred Koenig, had seen enough, and McBride was moved up to Triple-A Tulsa. “I think you’re ready to play in Triple A,” Koenig told him. “And what’s more, I think you’re ready to go to St. Louis.”11

Koenig was on to something as McBride batted .322 and stole 42 bases between the two leagues. He earned an invitation to the Cardinals’ spring training the following year. But he pulled a back muscle early on and then tore a muscle in his left shoulder. He could not get going and returned to Tulsa.

But McBride made his way back to the big leagues, and made his major-league debut on July 26, 1973, at Busch Stadium. With the Cards comfortably in front of the Mets, 10-1, McBride replaced Lou Brock in left field in the sixth inning. He got his first hit in the eighth inning, an RBI single to right field off Jim McAndrew.

Future Hall of Famer Brock set a National League record in 1974 with 118 stolen bases. McBride swiped 30 bases, second on the team. “Like any rookie, Bake had to reach one level at a time,” said Brock, “but I never saw him frustrated. When he learns pitchers’ moves and gets on base enough times to perfect his timing, he’s going to pour on the stolen bases.”12 But McBride was much more than a stolen-base threat. He batted .309, and was second on the team to Brock in hits (173) and runs (81). McBride was the starting center fielder for the Cardinals, flanked by Brock in left and Reggie Smith in right field. He was selected as the National League Rookie of the Year in 1974 by the Baseball Writers Association of America.

In spite of being on the disabled list for three weeks in 1975 because of torn fibers in his left shoulder, McBride continued his thievery on the bases. He batted an even .300 and finished second to Brock in stolen bases with 26. (Brock had 56.) In 1976 McBride was batting .335 when his season was cut short in early August to have cartilage removed from his knee. His left knee had been giving him trouble with constant aching. Many of the National League stadiums used the hard artificial surface of the day, and McBride felt that compounded his knee problem. His frequent injuries brought about skepticism over his desire to play baseball. “Bake had a bum rap attached to him,” said Brock. “I was hearing that he only played when he felt like it and all that stuff. I’ve seen him in the outfield when he never should have been in uniform. I admire the guy for doing that. But because of that kind of label, it can be damaging to his career.”13

Just two years after finishing in second place in the East Division of the National League, St. Louis sank to fifth place, 29½ games behind Philadelphia, in 1976. Schoendienst was replaced by Vern Rapp for the 1977 season. McBride and Rapp did not start off the best of terms when Bake arrived at spring training early. Rapp insisted that McBride shave his beard. From there, it was a downhill relationship, compounded by nagging soreness in McBride’s left shoulder.

On June 15, 1977, the Cardinals dealt McBride and pitcher Steve Waterbury to Philadelphia. In exchange, the Cardinals received pitcher Tom Underwood and outfielders Rick Bosetti and Dane Iorg. “(McBride) has had potential all along,” said St. Louis general manager Bing Devine. “But he’s been sidetracked by a lot of injuries. Sometimes a change of scenery works out for the best to a player.”14 McBride let his feelings known. “I was very happy playing for Red Schoendienst,” said Bake.” He’s a low-key guy. Then Vern Rapp came to St. Louis, and either you did it his way or you didn’t play.”15

Phillies backup outfielders Jay Johnstone and Jerry Martin were not exactly overjoyed by the addition of McBride. Their playing time would be curtailed as McBride took his place in right field alongside Greg Luzinski and Garry Maddox. But manager Danny Ozark was pleased with his new outfielder. “Bake gives us what we need, a leadoff hitter,” said Ozark. “I don’t think left-handers bother him that much. I know he always got his hits against Steve Carlton and Underwood.”16

But neither Devine nor Ozark may have envisioned just great an impact McBride would have in the Phillies’ lineup. Inserted in the leadoff spot for most games, he batted .359 (.316 for the season) with 10 homers and 36 RBIs. He stole 27 bases, second on the team to Larry Bowa’s 32 thefts. One of his round-trippers was a three-run clout at Wrigley Field on August 13 to lift the Phillies to a 10-7 victory over Chicago in 11 innings.

The Phillies held off the Pirates to win the NL East by five games. For McBride, October baseball would be a new adventure. “I’m really looking forward to it,” he said. “I really want to see what it’s like. I want to see if I’ll go, ‘Wow, I never dreamed I’d be here.’ Right now I can just imagine how other guys first felt when they got here.”17

But the Los Angeles Dodgers had other ideas, disposing of Philadelphia in four games in the NLCS. McBride homered in Game Two, but that was the extent of his highlights for the series.

The 1978 season was the first time in his major-league career that McBride did not hit at least .300. He finished with a .269 batting average. The Phillies led the Pirates by five games heading into September, and posted a 19-13 record in the final month (plus one game in October). They needed every victory as Pittsburgh closed fast with a 22-9 record, finishing a game and a half behind the Phillies in second place.

Philadelphia was matched up again with the Dodgers in the NLCS. The Dodgers finished off the Phillies in four games once again. As he did in 1977, McBride hit a home run, but he batted only .222 in the series.

In 1979 Pittsburgh ended the Phillies’ three-year reign atop the NL East. Philadelphia slumped to fourth place. Dallas Green replaced Ozark in the last month of the season. One positive for McBride was that he played in 151 games and was free from serious injury. It was the most games he played in his career, exceeding the total from his rookie year by one.

The 1980 Phillies squad was indeed a powerful one. Pete Rose had come to the team the previous season, and with Mike Schmidt, Larry Bowa, Manny Trillo, and Bob Boone to go along with the outfield of Luzinski, Maddox, and McBride, they were a formidable bunch. Steve Carlton led the staff with a league-leading 24 wins and 286 strikeouts. Lonnie Smith and Keith Moreland provided punch off the bench.

As the curtain came down on the month of August, the Phillies were tied with the Expos in second place, a half-game behind Pittsburgh. Philadelphia and Montreal emerged as the sole contenders with strong September records, the Phillies 19-10 and the Expos 19-9. Pittsburgh slumped with a 10-17 record in September.

Montreal held a half-game lead and the season game down to a three-game series with the Phillies at Olympic Stadium. The Phillies won two of the three games to lock up the division. Their opponent in the NLCS was the Houston Astros, the NL West winners. The Phillies won the best-of-five series to clinch a return trip to the World Series for the first time since 1950.

Their opponents in the Series were the Kansas City Royals. The American League champs had come up short in recent ALCS battles, losing three straight years to the New York Yankees (1976-78), mirroring the Phillies’ battles with Cincinnati and Los Angeles. Now the Royals were making their first appearance in the fall classic.

The Phillies won the world championship, the franchise’s first, in six games. Steve Carlton won two games to lead the way and Mike Schmidt was the MVP with two home runs and a .381 batting average. McBride was a big contributor to the Phillies’ cause, belting the team’s only other homer, a Game One three-run shot off Dennis Leonard. “Bake’s homer crushed it for me,” said Dallas Green. “He’s been a clutch guy and an RBI guy all season. He’s given us everything we asked for in 1980.”18

The players strike that began on June 12, 1981, led to the cancellation of 713 major-league games. After the strike ended and play resumed in August, the season was split. The Phillies won the first half in the NL East, with Montreal capturing the second half. The Expos bested the Phillies in the five-game division series, three games to two.

The Phillies began to dismantle their club in the offseason. Green left Philadelphia for Chicago, where he was the new general manager of the Cubs. He took Moreland and Bowa with him. Smith and Boone also departed. On February 15, 1982, the Phillies sent McBride to Cleveland for relief pitcher Sid Monge. For McBride, a transition to Cleveland, which played on natural grass, would be a welcome change from the artificial turf of Busch and Veterans Stadiums.

But the injury bugaboo caught up with McBride again. After he played just 27 games in 1982, an infection in his right eye sidelined him the last four months of the season. The infection progressed to the point that McBride thought he might lose his eyesight. A partial tear in the rotator cuff of his right shoulder cut out six weeks of playing time in the middle of the 1983 season. He missed two weeks later in the season because of torn ligaments in his left thumb. It was unfortunate, because while McBride was in the lineup he was a productive player. In his two years with the Indians, McBride batted .311, but had only 315 at-bats. “I’d like to have a full season where I can show the people of Cleveland what I can do,” said McBride. “I have hit all my life and I can still hit. But in my two years with the Indians, it has been one injury after another.”19

The Indians dropped McBride at the end of the 1983 season. He hooked on with Oklahoma City of the Double-A Texas League in 1984. But his season lasted only 32 games. McBride retired from baseball. His major-league batting average was .299 over 11 seasons. He hit 63 home runs and 167 doubles, and had 430 RBIs and 183 stolen bases.

In retirement, McBride was a roving coach with the New York Mets and the Cardinals for several years over the next two decades. The baseball field at Carver Park in Fulton, Missouri, is named in his honor.

Last revised: November 17, 2016

Notes

1 Neal Russo, “Cardinals Shade Mets in 25 Innings,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 12, 1974: 1-B

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Joseph Durso, “Baseball’s Longest Night For Mets Ends 3½ Hours Before Sunrise,” New York Times, September 13, 1974: 44.

6 Hal Lebovitz, “Bake McBride Won’t Talk?” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 28, 1982: 2-B.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Bob Broeg, “Whoosh! That’s Bake McBride, New Fulton Flash,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 11, 1973: 2B.

11 John Ferguson, “A ‘Reluctant Rookie’ Turns Tiger With Tulsa,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1972: 39.

12 McBride’s File, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

13 Dick Kaegel, “Season Over for McBride. …Wait Till Next Year,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 8, 1976: 1C.

14 Neal Russo, “Cards Get Eastwick, Send McBride to Phils,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 16, 1977: 8C.

15 Neal Russo, “Redbirds Died Away From Home and Loved Ones,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1977: 7.

16 Ray Kelly, “Bake Sale Leaves Some Sour Tastes in Philly,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977: 8.

17 Skip Myslenski, “I Really Want to See What It’s Like; Wow, I Never Dreamed I’d Be Here,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 4, 1977: 11.

18 Bill Lyon, “Homer and Two Singles Help Ease McBride’s Pain,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 15, 1980: 6-B.

19 Terry Pluto, “Has McBride Played Finale for the Tribe?” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 17, 1983: 2-E.

Full Name

Arnold Ray McBride

Born

February 3, 1949 at Fulton, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.