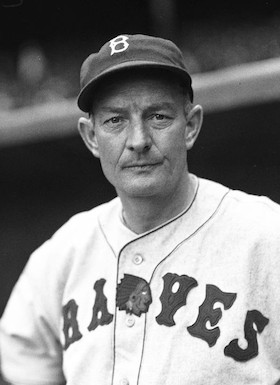

Bill McKechnie

This article was written by Warren Corbett

This article was published in SABR 50 at 50

This article was selected for inclusion in SABR 50 at 50: The Society for American Baseball Research’s Fifty Most Essential Contributions to the Game.

Twelve managers have won more games than Bill McKechnie. None has won more respect.

Twelve managers have won more games than Bill McKechnie. None has won more respect.

Deacon Bill McKechnie was the first to lead three different teams to the World Series and the first to win championships with two different teams. In 25 seasons as a manager, between 1915 and 1946, he earned respect as a baseball strategist and even more respect as a human being. “He is the sort of man that other decent men would want their sons to play for,” baseball historian and Cincinnati Reds fan Lee Allen wrote.1

McKechnie achieved the stature of a baseball saint only late in his career. His bosses didn’t always treat him with respect. His first two National League managing jobs ended in humiliation.

McKechnie was a gifted team builder. Even when he took over sorry clubs, he never had more than two losing seasons in a row. He built teams that were more than the sum of their parts by getting the most out of each individual. “McKechnie was a master handler of men,” Allen wrote. “Some managers will never learn to handle personalities as long as they live. McKechnie in that department was without a peer.”2

His secret was no secret, McKechnie said: “Just treat them the way you’d like to be treated.”3 He thought managers who delivered rah-rah speeches or clubhouse rants were showboats or fools. “A manager tries to pick his men carefully, keeping out the bad actors. But the average ballplayer plays [for] himself. He isn’t hustling for the manager or the club owner. He’s hustling for his own contract – his family and his future.”4

Sounds simple. But in a time when most managers were tyrants like John McGraw or ironfisted disciplinarians like Joe McCarthy, McKechnie’s fatherly approach was rare. In many ways he anticipated today’s manager, who must persuade young multimillionaires to be team players.

McKechnie was also a throwback, a relic of the deadball game in the longball era. He emphasized defense and pitching above all else. Most managers give lip-service to the virtues of stingy defense. To McKechnie, that was not just a cliché but a religion. He played the percentages faithfully because he believed the percentages would always win in the long run. He pleaded guilty to managing by the book: “Show me a manager who isn’t and I’ll show you a manager who loses a lot of games he ought to win.”5

William Boyd McKechnie was born in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, on August 7, 1886, one of 10 children of Scottish immigrants Archibald McKechnie and the former Mary Murray.6 The household also included three adopted children. Bill remembered marching to church with his brothers, all wearing kilts. His parents were Presbyterian, but Bill became a pillar of the Mifflin Avenue Methodist Church. Although he was never a deacon, he sang baritone in the choir for much of his adult life. He married his high school girlfriend, Beryl Bien, who said, “He told me the first time he saw me, he got so excited, he swallowed his chewing tobacco.”7

McKechnie’s playing career was forgettable, but his eagerness and intelligence impressed some of the game’s biggest names. A switch-hitting and seldom-hitting infielder, he dropped out of high school to play semipro ball, then graduated to the low minors. The Pittsburgh Pirates acquired his contract in 1907. When he made the big league club three years later, the Pirates’ superstar, Honus Wagner, took a liking to the hometown boy. McKechnie said Wagner taught him more about baseball than anyone else.

Landing with the New York Yankees in 1913, he became a favorite of the crusty manager, Frank Chance. Asked why he spent so much time with a benchwarmer, Chance replied, “Because he’s the only man on this club who knows what baseball is all about.”8

McKechnie’s career was going nowhere, so he jumped to the outlaw Federal League in 1914. He batted .304 as the regular third baseman for the pennant-winning Indianapolis Hoosiers. After the franchise moved to Newark the next year, the 28-year-old McKechnie took over as manager in June and led the club to a 54-45 record and a fifth-place finish.

When the Federal League folded after the 1915 season, John McGraw of the New York Giants picked up McKechnie’s contract along with that of his Newark teammate and friend, outfielder Edd Roush. In August 1916 McGraw traded his washed-up pitching ace, Christy Mathewson, to Cincinnati so Matty could become the Reds’ manager. McGraw told Matty he could take two players with him; Matty picked Roush and McKechnie.

Roush became the Reds’ star center fielder. McKechnie took up residence on the bench. He was sold back to Pittsburgh and finished his playing career in the minors in 1921.

The next year the Pirates hired him as a coach for manager George Gibson. Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss had already identified McKechnie as a future manager. The club was one game under .500 on June 30, 1922, when Gibson resigned and the 35-year-old McKechnie replaced him.

Despite their problems, the Pirates were a team on the rise. The lineup featured three future Hall of Famers: shortstop Rabbit Maranville, third baseman Pie Traynor, and center fielder Max Carey, the league’s perennial stolen base leader. Lefty Wilbur Cooper and curveball specialist Johnny Morrison anchored the pitching staff. McKechnie brought the club home in third place with an 85-69 record.

Over the next two years, McKechnie and Dreyfuss methodically improved the team. Outfielder Kiki Cuyler cracked the lineup in 1924 and batted .354/.402/.539. McKechnie picked up a 31-year-old rookie pitcher, Remy Kremer, from the Pacific Coast League, and he won 18 games. Dreyfuss bought minor league shortstop Glenn Wright. McKechnie took one look at Wright’s powerful arm and moved Maranville to second base.

The tiny Maranville was one of the game’s most popular players and one of its premier hell-raisers. In an effort to curb his night prowling, McKechnie roomed with him and his running mate, pitcher Moses Yellow Horse. One night the pair lured a flock of pigeons into the manager’s hotel room and locked them in the closet for him to find. For some reason, the soused Rabbit became a favorite of the teetotaler McKechnie.

The Pirates won 90 games in 1924, but finished third for the third straight year. After the season Dreyfuss and McKechnie traded three players reported to be discipline problems – Maranville, Cooper, and first baseman Charlie Grimm – to the Chicago Cubs for second baseman George Grantham, pitcher Vic Aldridge, and rookie first baseman Al Niehaus.

Some writers thought the Cubs had locked up the pennant, but McKechnie had a plan. He shifted Grantham to first base and installed young Eddie Moore at second. With Wright and Traynor, all four Pirates infielders had started out as shortstops. An infield full of shortstops would become a McKechnie trademark as he sought to construct the strongest possible defense.

The refurbished 1925 team stood barely above .500 in June when Barney Dreyfuss, one of baseball’s smartest and most successful owners, made a move so stupid it defies explanation. Fred Clarke, the Pirates’ player-manager in the glory days of Honus Wagner, had bought stock in the team and was appointed vice president, chief scout, and assistant manager. Dreyfuss sent him to sit on the bench with McKechnie. Although Clarke had been out of the game for a decade, Dreyfuss evidently thought he would bring old-school fire to an underachieving club. It was an insulting vote of no-confidence in the young manager, but Clarke was a local hero and Dreyfuss was the boss. McKechnie had to take it or quit.

Clarke, who had struck oil on his Kansas ranch, didn’t need the job and didn’t covet McKechnie’s; he hoped to buy the team from the aging Dreyfuss. The sportswriters dutifully reported that Clarke and McKechnie worked together in blissful harmony, but Clarke’s hard-driving personality could not have been more different from the manager’s, and he was never shy about voicing his opinion, whether the players wanted to hear it or not.

The Pirates charged into a tight pennant race with the Giants until Pittsburgh took command with a 16-3 run in August and September. The Pirates bludgeoned the rest of the league. They were the first National League club in the 20th century to score more than 900 runs, almost six per game, and led in batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage. Pittsburgh’s 95-58 record was 8½ games better than the Giants’.

The Pirates faced the defending champion Washington Senators in the World Series. The Senators took three of the first four games, with their saint, Walter Johnson, claiming two of the victories. Pittsburgh fought back to win the next two, forcing a Game Seven.

The deciding game played out in an unrelenting downpour. McKechnie’s starter, Vic Aldridge, lasted only one-third of an inning as the Senators scored four times in the first. The Pirates hit Johnson hard and trailed by just 7-6 when they came to bat in the bottom of the eighth. Forbes Field was a swamp of mud sprinkled with sawdust, but Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis was determined to complete nine innings.

With two out, Earl Smith and Carson Bigbee hit back-to-back doubles to tie the score. After a walk, Max Carey’s grounder should have ended the inning, but Senators shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh threw the ball away – his record-setting eighth error of the Series. Bases loaded.

Washington manager Bucky Harris stuck with his weary ace. As the rain streamed down Johnson’s face, writer Dan Daniel said, “He looked like he was crying his head off.”9 Kiki Cuyler sliced a line drive that bounded into the temporary bleachers in right field, bringing home the two winning runs.

It was Pittsburgh’s first championship since 1909, when guess-who was the manager. Some sportswriters gave Clarke as much credit as McKechnie. Critics in the press believed McKechnie was too soft to be a leader. “Players behind his back laughed at him, kidded about his judgment,” Regis M. Welsh of the Pittsburgh Post wrote later. “The general consensus was that the club won in spite of him.”10

Dreyfuss added to the Pirates’ powerful lineup for 1926 when he bought Paul Waner, a little left-handed batter who had hit .401 in the Pacific Coast League. Slashing line drives all over the field, Waner batted .336/.413/.528 in his rookie year. Pittsburgh had climbed into first place in August when it all fell apart.

Team captain Carey, slumping and sick of Clarke’s carping, wanted the shadow manager removed from the dugout. Two other elders, pitcher Babe Adams and outfielder Carson Bigbee, agreed, but their teammates voted down the motion by a reported 18-6 landslide. Carey thought Clarke had intimidated the other players.

News of the vote inevitably leaked to the press. One headline screeched, “MUTINY.”11 The rebellious players were likened to anarchists and communists. At this critical moment, Barney Dreyfuss was on vacation in Europe, leaving his son, Sam, and Clarke in charge. Clarke decreed that the mutineers had to go, and Sam Dreyfuss swung the axe. Adams and Bigbee were released. Carey was suspended, then sold to the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The newspapermen agreed that the popular Clarke was an innocent victim of a sinister plot, but they couldn’t agree on who was the greater villain, the mutinous players or the manager who had failed to quash the rebellion. The Pirates fell under .500 for the rest of the season and wound up in third place.

When Barney Dreyfuss returned home, he had little choice but to back his son’s decision. And he claimed he had no choice but to fire the manager because the fans demanded it. One year after winning the World Series, McKechnie was unemployed.

Reflecting on the upheaval, the Post’s Regis Welsh gave the departing manager a kick on his way out of town: “McKechnie showed, more than ever, the weakness that had been typical of him.”12 The Pittsburgh mutiny could have ended McKechnie’s career. He had been found guilty of a manager’s unforgivable sin: He had lost control of the clubhouse. His failure was underscored the following year, when new manager Donie Bush, without Clarke’s advice, led the Pirates to another pennant.

McKechnie found work as a coach for the St. Louis Cardinals under first-year manager Bob O’Farrell. The Cardinals had won their first pennant and World Series in 1926, but player-manager Rogers Hornsby was traded after the season because he couldn’t get along with the owner, Sam Breadon (or practically anybody else). O’Farrell, a 30-year-old catcher who had been named NL Most Valuable Player in 1926, didn’t want the job. He leaned heavily on McKechnie, occasionally calling time in mid-inning to go to the bench and consult his assistant.

The 1927 Cardinals won 92 games, three more than in their pennant year, and stayed in the race until the final weekend before finishing second. That wasn’t good enough for Breadon, who panicked easily and often. He made McKechnie the Cardinals’ fourth manager in four years.

As in Pittsburgh, McKechnie took over a strong team. Second baseman Frankie Frisch, acquired in a trade with the Giants for Hornsby, was the sparkplug. First baseman Jim Bottomley had his career year in 1928, and left fielder Chick Hafey wasn’t far behind. McKechnie brought back Rabbit Maranville, who had dropped to the minors and quit drinking, to put a fourth future Hall of Famer in the lineup. A veteran trio—Bill Sherdel, Jesse Haines, and 41-year-old Grover Cleveland Alexander—led the pitching staff. The Cardinals moved into first place in June and won 11 of their last 15 games to outrun the Giants.

That set up a World Series rematch with the Yankees, the team St. Louis had defeated in seven games in 1926. The 1928 Series lasted only four. The Cardinals lost the first three, then took a 2-1 lead in Game Four. Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig hit back-to-back home runs to finish them off. McKechnie’s club was not only beaten, but swept; not only beaten and swept, but stomped. The Yankees outscored the Cardinals 27-10 and never even needed a relief pitcher.

Sam Breadon was not happy with the outcome, and when the owner was not happy the manager took the fall. Breadon had dumped Hornsby after he won a World Series. McKechnie could expect no better after losing one. The New York Times’s John Kieran wrote, “The charge against McKechnie is that ‘he is one of the finest fellows in the world, but —.’”13

Breadon didn’t just fire the manager; he demoted him to the minors. McKechnie swapped jobs with Billy Southworth, who had led the Cards’ top farm club at Rochester to the International League pennant. Again, McKechnie had to swallow the humiliation to keep his paycheck.

Southworth had managed only one year in the minors. At 36, he was now managing major leaguers who had been his teammates two seasons before. Southworth decided he had to get tough to show the players who was in charge. He only succeeded in alienating most of the team.

The Cardinals lost a doubleheader on July 21 to fall 13½ games behind the first-place Pirates. Breadon, back in panic mode, spun his revolving door: Southworth and McKechnie swapped jobs again. Breadon admitted he had made a mistake when he sent McKechnie down.

The Cardinals played better under their new-old manager, but not particularly well. They went 34-29 and stayed in fourth place, finishing 20 games back. Even before the season ended, McKechnie signaled that he had had enough of Sam Breadon. He announced his candidacy for tax collector in his hometown, Wilkinsburg. “If elected, I’m through with baseball,” he said. “If not, well, I guess I’ll have to return to the old game.”14 Beryl McKechnie campaigned hard for her absent husband, and Cardinals vice-president Branch Rickey came to town to endorse him, but the voters rejected him in the September Republican primary.

McKechnie returned to the old game in a new spot. Breadon offered him a one-year contract to stay in St. Louis. Instead, he accepted a four-year deal to manage the Boston Braves in 1930. Security was all the new job had going for it. The Braves were a last-place team and had had one winning season in the past 13. The principal owner, Judge Emil Fuchs, managed the club in 1929 to save a salary. The Braves were usually near the bottom in attendance as well as in the standings.

The team’s best players were on the downside of the hill. First baseman George Sisler was a husk of the .400 hitter he had been. Shortstop Rabbit Maranville (him again) was 38. The rest of the roster was what you’d expect from a team that lost 98 games.

For the first time, McKechnie had full authority over player personnel. What he didn’t have was money. Fuchs and McKechnie employed creative financing to acquire a new foundation player. They sold third baseman Les Bell to the Chicago Cubs and used the cash, reported to be at least $35,000, to buy center fielder Wally Berger from the Cubs’ Los Angeles farm club. Berger had hit 40 home runs in the Pacific Coast League. In 1930 his 38 homers for Boston set a major league rookie record that stood for more than half a century.

In three years McKechnie turned over the roster almost completely. The Braves reached .500 in 1932. The next year they made an unlikely run at the pennant.

On August 20 the Braves won a doubleheader from Pittsburgh and climbed into a virtual tie for second place, 7½ games behind the New York Giants. They went on to win eight in a row. McKechnie said his men thought they couldn’t lose: “They’re singing that song about being in the money and they mean every word of it.”15

The season reached its high tide on August 31, when a victory over the Giants boosted the club within five games of first place. The next day a crowd estimated at 50,000 overflowed Braves Field for a Friday doubleheader, said to be the largest weekday turnout in Boston history. The Giants swept both games, then won the next two to pop McKechnie’s pennant bubble.

In the season finale, Wally Berger, benched by the flu, came on as a pinch-hitter and powered a grand slam into the left-field stands to beat Philadelphia. The blow clinched fourth place with an 83-71 record, the Braves’ first finish in the first division in a dozen years. The players were “in the money”; each man collected about $400 as a World Series share.

McKechnie had built a tight defense – second in the league in defensive efficiency – that transformed a staff of no-name pitchers into winners.16 Left-hander Ed Brandt, who had developed under McKechnie, was fourth in the NL in ERA. Two others, Ben Cantwell and Huck Betts, were in the top 10. With just about the same team in 1934, the Braves finished fourth again, winning 78 games.

The club had been on shaky financial ground for years. Now the ground collapsed under Judge Fuchs. When he fell behind on the rent, his Braves Field landlord threatened to void the lease and turn the ballpark into a dog-racing track. The National League assumed the lease, permitting Fuchs to remain in charge, and Boston civic leaders launched a campaign to sell tickets so the Braves could afford to go to spring training.

Fuchs took a desperate step to save the franchise. He signed the game’s biggest drawing card and embarrassed his manager in the process.

Babe Ruth wanted to manage the Yankees. The Yankees wanted to be rid of him, but they needed to ease him out the door without alienating his fans. Fuchs offered Ruth a contract to join the Braves as a player, vice president, and assistant manager, with a wink that the Babe could become manager in a year. Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert agreed to release Ruth so he could take advantage of this wonderful opportunity in the city where his major league career began.

When Fuchs put the offer in writing, he composed a masterpiece of lawyerly evasion, filled with half-promises, or maybe quarter-promises, that Ruth might manage the team if this and if that and if the other. The Bambino was being bamboozled.17

McKechnie was not consulted. In Florida preparing for spring training, he read in the papers that he might be kicked upstairs to the front office. He asked a reporter, “What would I do in an office?”18

Ruth was fat and 40, but Fuchs didn’t care whether he could play as long as he sold tickets. On Opening Day 1935 everybody’s dreams came true. Ruth slammed a homer off the league’s best pitcher, Carl Hubbell, and accounted for all of Boston’s scoring in a 4-2 victory over the Giants.

It went downhill from there. Opening Day was the only day the team was above .500. Ruth struck out 15 times in his first 15 games and was a statue in left field. He was ready to quit, but Fuchs persuaded him to make a road trip to the western cities, where his appearance had already been advertised. He summoned memories of his former self in Pittsburgh when he hit three home runs in one game, the last one clearing Forbes Field’s roof and bouncing off a house an estimated 600 feet from the plate.

The sad end came on June 2. Ruth, batting .181, told the writers he was going on the voluntarily retired list, but Fuchs said he couldn’t quit because the club had already released him.

The Braves’ record stood at 9-24 when Ruth played for the last time. Their season was ruined, but not by him; they got worse after he left. McKechnie had no decent players to trade and no cash to buy new ones. The Braves’ 115 losses were the most by a National League team in the 20th century until the expansion Mets were born.

Judge Fuchs had run out of money, credit, and hope. Before the 1936 season the National League took over the franchise and engineered a recapitalization with the longtime baseball executive Bob Quinn as principal owner. The 65-year-old Quinn had a knack for picking lost causes. He had owned the Red Sox after Harry Frazee plundered the team and then served as president of the debt-ridden Brooklyn Dodgers.

Quinn changed the team nickname to Bees but kept the manager. McKechnie started rebuilding again. He acquired a few useful players, including Al Lopez and Tony Cuccinello, possibly as an act of charity by the rest of the league, and improved the club’s record by 33 wins in 1936, good enough for sixth place.

McKechnie overhauled his pitching staff for 1937. Still short of money, he tried out several veteran minor leaguers who came cheap because they were too old to be prospects. He molded two of them into the biggest surprises of the year. Jim Turner, an offseason milkman in Nashville, Tennessee, was 33 and had rattled around the minors for 14 seasons. Lou Fette turned 30 during spring training. Both were breaking-ball pitchers who induced ground balls, and McKechnie put the league’s best defense behind them.

The 1937 Braves allowed the fewest runs and the fewest walks while leading the league with 16 shutouts. But they also scored the fewest runs. In the season’s next-to-last game, the aged rookie Turner beat Philadelphia for his 20th victory and lowered his ERA to a league-best 2.38. The next day Fette won his 20th, a seven-hit shutout.

Boston closed with a rush, winning eight of the last 10 to finish fifth with a 79-73 record. The Sporting News named McKechnie Manager of the Year because “he has been able to make much out of little.”19 Gray-haired, wearing rimless bifocals on his sun-creased face, he was the National League’s senior manager at age 51.

McKechnie had endured eight years of turmoil and poverty in Boston. Now he found himself in demand; four teams reportedly wanted him. The Cincinnati Reds bid highest. Their wealthy owner, Powel Crosley Jr., gave him a two-year contract at a reported $25,000, plus an attendance bonus. The salary was said to be third highest for any manager, behind Bill Terry and Joe McCarthy of the pennant-winning New York clubs.

The Reds were a last-place team, but for McKechnie they had an additional attraction beyond money. The general manager, Warren Giles, was a friend and admirer. He had been business manager at Rochester when McKechnie was in exile there. New to his job, Giles followed the manager’s lead in decisions on playing personnel.

McKechnie’s first three years in Cincinnati secured his place in baseball history. Taking on a habitual loser once more, he retooled the club to win two consecutive pennants and iced the cake with a World Series championship. That success earned him national recognition as the game’s finest Christian gentleman since Christy Mathewson. And four decades later, when oral histories became popular, many of his Reds players were still alive to pump up his legacy.

Giles and McKechnie embarked on an extreme makeover. They kept Ernie Lombardi, the NL’s best-hitting catcher, but dumped two faded stars, Kiki Cuyler and Chick Hafey, and handed center field to rookie Harry Craft, a light-hitting glove man. First base was awarded to Frank McCormick, who was big and slow but hit smoking line drives. McKechnie turned Lonny Frey, a poor shortstop, into an excellent second baseman.

Midway through the 1938 season the Reds traded for Wally Berger, another power bat to go with Lombardi and right fielder Ival Goodman, and acquired Bucky Walters, a converted third baseman who had had little success on the mound. He perked up when he got away from the weak Philadelphia Phillies.

Johnny Vander Meer’s back-to-back no-hitters were the highlight of the season. Lombardi won the batting title and the MVP award, McCormick led the league in hits, and Goodman belted a team-record 30 home runs (Giles had shortened Crosley Field’s fences). Cincinnati scored the most runs per game in the league. In late June the Reds surged to within 1½ games of first place. They slipped back to finish fourth with an 82-68 record, only six games behind the pennant-winning Cubs.

The Reds completed their lineup makeover when they acquired third baseman Bill Werber from the Philadelphia Athletics during spring training in 1939. A three-time American League stolen base leader, he gave the team a speedy leadoff man, though he didn’t steal many in McKechnie’s conservative offense.

Werber, a confident and intense Duke University graduate, became the leader of the infield. He nicknamed the quartet “the Jungle Cats,” calling himself “Tiger,” shortstop Billy Myers “Jaguar,” and second baseman Frey “Leopard.” First baseman McCormick objected to Werber’s teasing choice, “Hippopotamus,” so he became “Wildcat.” Bucky Walters and the veteran workhorse Paul Derringer, both sinkerballers, turned into aces with the Jungle Cats pouncing on ground balls behind them. McKechnie made sure the infield grass at Crosley Field stayed high and damp to slow down those grounders.

McKechnie liked durable pitchers who threw strikes and finished what they started. Walters and Derringer filled the bill. They topped 300 innings apiece in 1939 and were first and second in the league in complete games. They started nearly half the Reds’ games and recorded more than half of the club’s 97 wins. Walters won the pitcher’s triple crown, leading the league in victories (27, against 11 losses), ERA (2.29), and strikeouts (137, tied with Claude Passeau), and was named NL Most Valuable Player. Derringer was 25-7, 2.93, with five shutouts and barely more than one base on balls per nine innings. Derringer, who was prone to drinking and fighting, often in that order, said, “If a pitcher can’t win for Bill McKechnie, he can’t win for anybody.”20

The Reds won 12 straight in May and climbed to the top of the standings, holding off the Cardinals to fly Cincinnati’s first pennant in 20 years. Their home attendance of almost one million led both leagues, even though Cincinnati was the smallest market in the majors.

The World Series matched the Reds against the Yankees, winners of their fourth consecutive American League pennant. It was no contest. New York won in four straight. The memorable moment was “Lombardi’s snooze,” when two Yankees crossed the plate in the 10th inning of Game Four while the Cincinnati catcher lay helpless on the ground after baserunner Charlie Keller kicked him in the testicles. (Those were not the winning runs; the tie-breaker scored before Keller ran over Lombardi.)

In the offseason McKechnie acquired his antiquated Boston ace, Jim Turner, to add a third reliable starter. Second-year right-hander Junior Thompson made four. The Reds started strong in 1940 and gathered steam as the season wore on. In July they won 18 of 20 to open a comfortable lead.

But getting there wasn’t easy. Injuries and batting slumps created holes in the outfield. Shortstop Myers left the club for several days in September, enraging his teammates. Worst of all, backup catcher Willard Hershberger killed himself on August 3.

Hershberger, filling in for the injured Lombardi, blamed himself for some lost games and became despondent. He was found dead in his hotel room with his throat slashed. “He told me what his problems were,” McKechnie said. “It has nothing to do with anybody on the team. It was something personal. He told it to me in confidence, and I will not utter it to anyone. I will take it with me to my grave.” He did.21

McKechnie’s club weathered the shock. Beginning August 31 the Reds went on a 19-2 run to finish with 100 victories, 12 games ahead of second-place Brooklyn. At least they wouldn’t have to face the Yankees in the World Series. The Detroit Tigers ended New York’s string of four straight pennants.

This time the Series went the distance before Cincinnati won behind the pitching of Walters and Derringer, and contributions from a pair of unexpected heroes. Jimmy Ripple, a waiver pickup who plugged the hole in left field, slammed a homer and drove in six runs. Forty-year-old coach Jimmie Wilson went on the active list after Hershberger’s suicide to replace Lombardi. Wilson caught six of the seven games and batted .353 while hobbling with charley horses in both legs.

The 1939 and 1940 Reds gave McKechnie his greatest triumphs. The teams not only won, they won his way: with pitching and defense. In both years Cincinnati allowed the fewest runs in the majors while recording the best defensive efficiency and the lowest opponents’ batting average on balls in play. The 1940 club’s 117 errors were the fewest in history to that point. The defensive efficiency rate – 73 percent of batters retired on balls in play – tied for the all-time best. Sportswriter Edwin Pope commented that Cincinnati “guarded home plate like it was the last penny in Fort Knox.”22

McKechnie won with a collection of mostly forgotten players. The Reds were the only team to win two straight pennants without a single Hall of Famer on the roster, until Lombardi was inducted nearly 50 years later. No other player came close to election.

When the club dropped to third place in 1941 and fourth in 1942, some of the players thought McKechnie showed too much loyalty to his slumping former stars. During the war years, as the military draft gutted the roster, McKechnie filled in with more over-the-hill veterans. In 1945 the depleted Reds fell to seventh place with their first losing record on McKechnie’s watch.

The return of real major leaguers in 1946 brought little improvement. McKechnie’s defense-first dogma produced a lineup that finished last in runs scored and sixth in the standings. While other teams basked in a postwar attendance bonanza, the Reds drew the smallest crowds in the league. Before the season was over, McKechnie resigned under pressure. “Those fans don’t know what’s good for them,” general manager Giles lamented. “They’ve just forced me to fire the best manager in baseball.”23

The 60-year-old McKechnie’s unemployment may have been the shortest in history. Even before he got out of town, Cleveland owner Bill Veeck tracked him down to hire him as a coach. Veeck didn’t think much of his manager, Lou Boudreau, who was also his star shortstop, but McKechnie insisted he would not manage again. Veeck made him the highest-paid coach in the game; his $25,000 salary was three or four times that of most coaches. The contract included a bonus based on attendance. When the Indians drew a record 2.6 million in 1948, McKechnie made around $47,000, more than any Cleveland player except Bob Feller.24

The arrangement was uncomfortable at first, bringing back echoes of Fred Clarke in Pittsburgh’s dugout, but Boudreau came to rely on the man he called “Pops.” McKechnie took primary responsibility for the pitching staff, which was the American League’s best when Cleveland won the ’48 pennant and World Series.

After Veeck sold the Indians in 1949, the new owners got rid of the high-priced coaches. McKechnie retired to his farm in Bradenton, Florida, where he grew tomatoes and citrus fruit. He had bought the land in partnership with his former catcher Jimmie Wilson and also owned a produce-shipping business. An investment in Texas oil wells with another of his former players, Randy Moore, paid off with comfortable incomes for McKechnie and several other baseball men, including Casey Stengel and Al Lopez. Edd and Essie Roush also retired to Bradenton; they lived just two blocks from the McKechnies, and the two wives were close friends.

When Boudreau became manager of the Red Sox in 1952, he wanted McKechnie as his pitching coach. At first McKechnie said he would only work with the team in spring training, but he agreed to a full-time job with his wife’s encouragement. “I know he misses his friends in baseball,” Beryl said. “I can tell every spring.”25

The same week that McKechnie joined the Red Sox, his son Bill Jr. was named Cincinnati’s farm director. Bill Jr. later served as president of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League. A grandson, also named Bill, was a minor league executive.

The Boston job lasted two years, until the team decided to go with younger and cheaper coaches. McKechnie retired for good. Beryl died in 1957. They had been married for 46 years and had two daughters and two sons.

In 1962 the Hall of Fame’s Veterans Committee voted McKechnie into Cooperstown. He was the fifth man to be elected as a manager, following Connie Mack, John McGraw, Wilbert Robinson, and Joe McCarthy. McKechnie was inducted with Jackie Robinson, Bob Feller, and his friend Edd Roush. At the ceremony he said, “Anything I’ve contributed to baseball I’ve been repaid seven times seven.”26 That’s how the newspapers reported it. McKechnie’s daughter Carol heard him say “seventy times seven,” a quotation from the Biblical book of Matthew.27

That summer two men barged into McKechnie’s home wearing bags over their heads. One waved a gun, the other an iron pipe. They demanded cash. The 75-year-old tried to talk them out of it, but when that didn’t work he grabbed a floor lamp and began swinging it like a Louisville Slugger. The thugs retreated as McKechnie hustled into his bedroom to get his shotgun. The frustrated pair got away without injury and without money.

In a fitting tribute, the city of Bradenton renamed its ballpark McKechnie Field. It is the spring home of the Pittsburgh Pirates and the home of their Class-A affiliate in the Gulf Coast League.

McKechnie contracted leukemia, which weakened his immune system, and died of pneumonia on October 29, 1965. His record shows 1,896 games won, 1,723 lost, with four pennants and two World Series championships, but his former players remembered his patience and decency. Pitcher Junior Thompson, who joined the Reds as a 22-year-old, said, “He and his wife were like parents to me.”28 Paul Waner recalled, “He could be a father to you when he felt he had to be and a taskmaster when that was needed.”29 Paul Derringer said, “In a sentence I’d say he was the greatest manager I ever played for, the greatest manager I ever played against, and the greatest man I ever knew.”30

Notes

1 Lee Allen, The Cincinnati Reds (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 255.

2 Ibid., 271.

3 Frank Graham, “Another Pennant for McKechnie?” Look, April 4, 1944, 42.

4 Ed Rumill, “An Interview with Bill McKechnie,” Baseball Magazine, June 1950, 247.

5 Joe Williams, “Deacon Bill McKechnie,” Saturday Evening Post, September 14, 1940, 89.

6 During his baseball career, McKechnie gave his birth year as 1887. He said he learned he was a year older when one of his sisters found the correct date in an old family Bible. In such a large family, it would be possible to confuse one child’s birth date, but it seems equally probable that McKechnie, like many other players, had subtracted a year for his “baseball age” and didn’t want to admit it. The Sporting News, November 13, 1965, 25.

7 Graham, “Another Pennant,” 44.

8 Frederick G. Lieb, “McKechnie, Flag-Winner in 3 Cities, Dead,” The Sporting News, November 13, 1965, 25. Lieb is the source of several versions of the Chance quote, some more colorful than others.

9 Jerome Holtzman, No Cheering in the Press Box (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1974), 13.

10 Regis M. Welsh, “M’Kechnie Suffers Penalty of Indecision,” Pittsburgh Post, October 19, 1926, 14.

11 “Two Veterans Walk Plank in Pirate Mutiny,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1926, 13.

12 Welsh, “M’Kechnie Suffers Penalty.”

13 John Kieran, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, October 23, 1928, 37.

14 Al Abrams, “McKechnie’s Plans Depend Upon Tax Collector Fight,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 8, 1929, 17.

15 Burt Whitman, “‘Let the Other Fellows Worry’ Is McKechnie’s Philosophy as Braves Resume War Dance,” Boston Herald, August 26, 1933, 7. “We’re in the Money” was a hit song from the Busby Berkeley movie musical “Gold Diggers of 1933.”

16 Defensive efficiency rate measures a team’s ability to convert batted balls into outs. The 1933 Braves’ rate was 71.6 percent.

17 Fuchs’s letter to Ruth is reprinted in Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (repr. New York: Penguin, 1983), 386-388.

18 “Bill McKechnie Goes About Business Despite Report Ruth Will Succeed Him,” Boston Herald, February 27, 1935, 16.

19 Edgar G. Brands, “Barrow, McKechnie, Allen, LaMotte, Flowers and Keller Win ’37 Accolades,” The Sporting News, December 30, 1937, 2.

20 Bill McKechnie page at the National Baseball Hall of Fame website, http://baseballhall.org/hof/mckechnie-bill, accessed August 19, 2015.

21 William Nack, “The Razor’s Edge,” Sports Illustrated, May 6, 1991. http://www.si.com/vault/1991/05/06/124126/the-razors-edge-as-the-cincinnati-reds-chased-a-pennant-in-1940-a-dark-family-legacy-tortured-the-mind-of-catcher-willard-hershberger, accessed September 9, 2015.

22 McKechnie page at the HOF website.

23 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, February 8, 1962, 49.

24 Bill Veeck with Ed Linn, Veeck as in Wreck (repr. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 155.

25 Bill Grimes, “Mrs. Bill McKechnie Hopes Hubby Stays with Red Sox,” Boston American, February 29, 1952, 8.

26 “Feller, Robby, Two Veterans Join Famers,” United Press International-Boston Record-American, July 24, 1962,

27 Mitchell Conrad Stinson, Deacon Bill McKechnie (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 214.

28 Talmage Boston, 1939: Baseball’s Pivotal Year (Fort Worth: Summit, 1990), 78.

29 Ed Rumill, “McKechnie Knew Plays, When to Use Them,” Christian Science Monitor, November 4, 1972, 11.

30 Bradenton Herald, November 2, 1965, quoted in Stinson, Deacon Bill McKechnie, 212.

Additional sources

“Guillotine Quickly Puts Down Anti-Clarke Rebellion.” The Sporting News, August 19, 1926.

Honig, Donald. The Man in the Dugout. Chicago: Follett, 1977.

Jackson, Frank, “Indian Summer at Braves Field.” The Hardball Times, March 27, 2015. http://www.hardballtimes.com/indian-summer-at-braves-field/

Jaffe, Chris. Evaluating Baseball’s Managers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010.

James, Bill. The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers. New York: Scribner, 1997.

Lowenfish, Lee. Branch Rickey, Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman. Lincoln and London: Nebraska, 2007.

Koppett, Leonard. The Man in the Dugout. New York: Crown, 1993.

Louisa, Angelo. “Fred Clarke.” SABR BioProject.

Ritter, Lawrence. The Glory of their Times. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

Ruane, Tom. “A Retro-Review of the 1920s.” Retrosheet.org.

http://www.retrosheet.org/Research/RuaneT/rev1920_art.htm. Accessed August 19, 2015.

_____. “A Retro-Review of the 1930s.” Retrosheet.org. http://www.retrosheet.org/Research/RuaneT/rev1930_art.htm

_____. “A Retro-Review of the 1940s.” Retrosheet.org. http://www.retrosheet.org/Research/RuaneT/rev1940_art.htm

Swope, Tom. “On the Pennant Path.” Cincinnati Post, August 16, 1939.