Negro League Baseball at Comiskey Park: The East-West Game, An All-Star Legacy

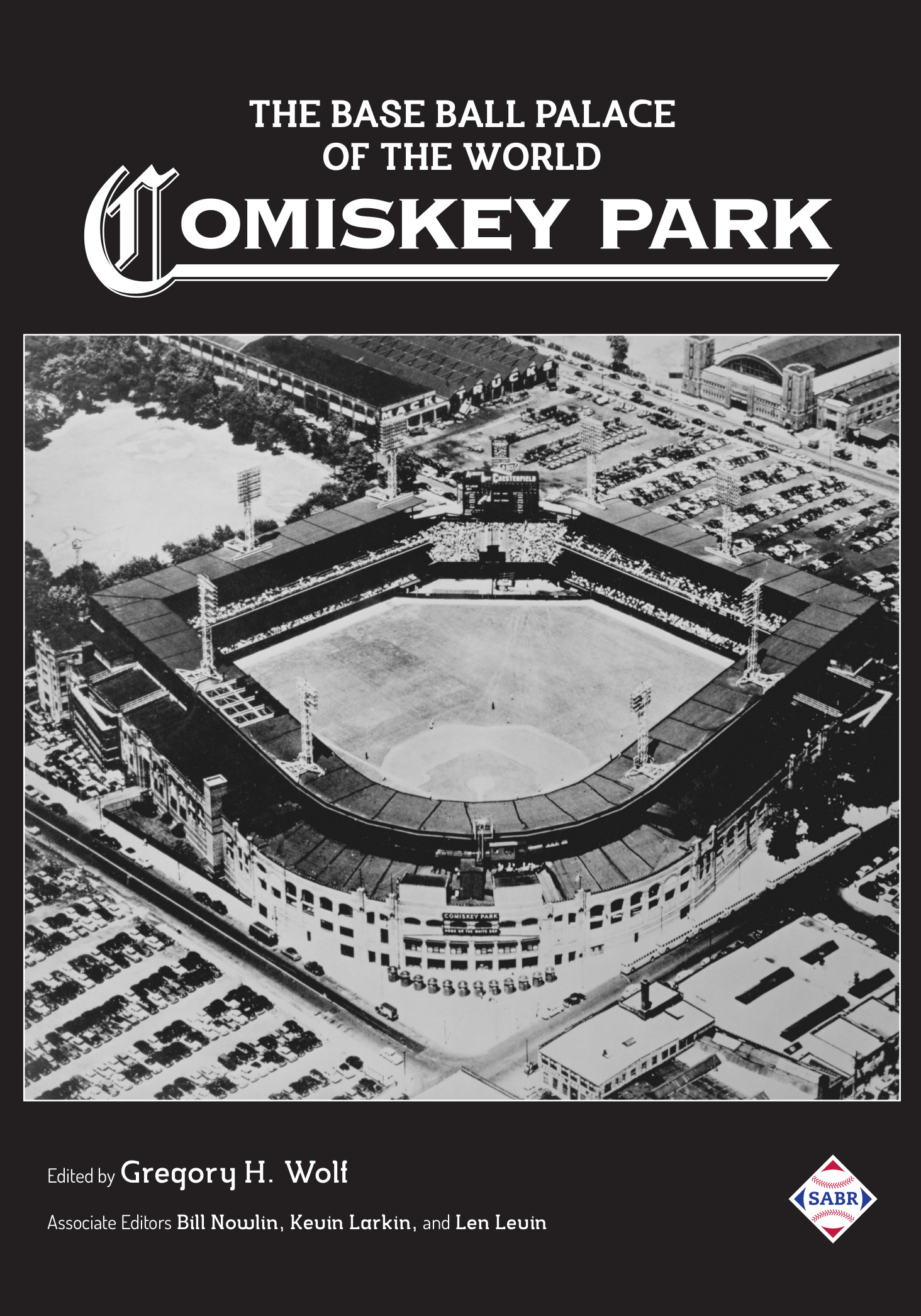

This article appears in SABR’s “The Base Ball Palace of the World: Comiskey Park” (2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

“It makes no difference if the nation is in the midst of a major depression or riding the wave of prosperity, the East-West game is always a rousing success. It is the biggest sporting event ever promoted by Negroes and has been a box office hit from the start.” – Wendell Smith, Pittsburgh Courier, 1949.1

“The game itself is more than a mere promotion. It’s our connecting link with organized baseball. It’s our big opportunity to show, under perfect conditions, just what we are capable of producing through the years.” – Bill Nunn, Pittsburgh Courier, 1937.2

The story of the 28 years of Negro League East-West All-Star Games at Comiskey Park was documented by the great black writers who covered the event over the years, especially in the Pittsburgh Courier and Chicago Defender. Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier relayed the reminiscences of J.B. Martin, longtime president of the Negro American League, when Martin spoke on the eve of the 1954 game.

The story of the 28 years of Negro League East-West All-Star Games at Comiskey Park was documented by the great black writers who covered the event over the years, especially in the Pittsburgh Courier and Chicago Defender. Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier relayed the reminiscences of J.B. Martin, longtime president of the Negro American League, when Martin spoke on the eve of the 1954 game.

“The first East-West game, twenty-one years ago, opened the eyes of millions of people, and each year thereafter, more and more fair-minded people came to realize that it was sheer hypocrisy to pretend that there weren’t any Negro players capable of playing in the major leagues. We were fortunate in that the players we had on exhibition (in the early years) were magnificent performers. There was for example Josh Gibson, one of the greatest hitters in the history of baseball; Willie Wells, the shortstop supreme; Ray Dandridge, the peer of all second basemen; James (Cool Papa) Bell, the swiftest outfielder in the game; and pitchers like Satchel Paige Willie Foster, Ray Brown, Leon Day, Joe Rogan, and others.”3

In 1933 the first game between representatives of the East (Negro National League) and the West (Negro American League) was played at Comiskey Park. It was the brainchild of Pittsburgh restaurateur Gus Greenlee, who owned the Pittsburgh Crawfords (NNL). Others involved in launching the enterprise were owner King Cole of the Chicago American Giants (NAL), writer Fay Young of the Chicago Defender, and writers Bill Nunn, Chester Washington, John Clark, and Roy Sparrow of the Pittsburgh Courier.4

The score was West 11, East 7. Cool Papa Bell of the East squad led off the game with a fly ball to left field. The wall between Negro League baseball and Organized Baseball was totally insurmountable and scant attention was paid to the exploits of Bell and the others in the predominantly white mainstream press. But the games went on and ultimately the players would get their due recognition. Ten players from the 1933 game went into the Hall of Fame, as did the East manager, Pop Lloyd.

George “Mule” Suttles played for the Chicago American Giants. The West won the games in 1933 and 1935 and Suttles homered in each game, his homer in 1935 winning the contest in the 11th inning. He was always among the top vote-getters, but when his career ended in 1944 – he was 43 – he was little known outside of the Negro Leagues. He was inducted at Cooperstown in 2006.

More than 20 players who participated in the 28 games at Comiskey Park have been enshrined at Cooperstown, but others have escaped long-term fame. Jim West of the Washington Elites was batting .419 on the eve of the 1936 game. The Kansas Whip introduced the player to its readers on August 21, 1936. As a first baseman, he “ranks head and shoulders above any man modern baseball has produced for color. He was known for his “floppy old glove, his halting stumbling stride, his Houdini tactics as he spears a high one or digs a low one out of the dirt.” The article’s author concluded by saying that “the shadows of (George) Sisler, (Lou) Gehrig, and others will hang their heads in shame over the almost unbelievable feats of Jim West.”5

West first played in the Negro Leagues in 1930 and continued to play until 1947. He, like so many others, would be denied the opportunity to play in Organized Baseball.

In 1936 the East team, stocked with future Hall of Famers from the Pittsburgh Crawfords, including Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell and Judy Johnson, romped to a 10-2 win to even the series at 2-2. Bell, had three hits, including a double, and Paige pitched the game’s final innings as his team broke the game open.

In 1937 several players, including Satchel Paige, elected to play in the Caribbean and Central America for bigger paychecks. Nevertheless, there was an abundance of talent, including eight Hall of Famers. Hall of Fame pitchers Hilton Smith (West) and Leon Day (East) contended with the Hall of Fame bats of six players. Buck Leonard anchored the East Squad along with Mule Suttles. Suttles was accompanied by Newark Eagles teammates Ray Dandridge and Willie Wells. The West outfield included Turkey Stearnes in center and Willard Brown in left.

Leonard took center stage, clouting a second-inning homer to start the scoring as the East won, 7-2. With one out in the fifth inning, Bill Wright, the East’s center fielder, made a great catch robbing the West’s Newt Allen, diving headlong to grab the Texas Leaguer. This was on the heels of an equally remarkable play by East shortstop Wells an inning earlier. Wells, appearing in his fifth straight East-West game, sprinted into center field to grab a fly ball off the bat of Ted Radcliffe. Leonard, well past his prime, played briefly, at age 45, in the Piedmont League in 1953.

On August 23, 1938, the West evened the series at three games apiece with a 5-4 win. The key blow was a three-run inside-the-park homer off the bat of the West’s Neil Robinson. Chicago Daily News sports editor Lloyd Lewis compared the Negro Leagues game to its white counterpart.

“The game was afire with speed. The bases were run with a swiftness and daring absent from the white man’s game for 20 years. Crafty runners kept pitchers worried, catchers throwing hastily, and infielders darting in and out to hold them to the bags. They stretched singles into doubles; they went down to first so fast that no infield double play succeeded on a ground ball.”6

The 1939 season marked the return of the “Bronze Abolisher of Peerless Pitchers.”7 Josh Gibson had rejoined the Pittsburgh Crawfords. The West Squad was led by Alex Radcliffe of the Chicago American Giants, the only player to appear in each of the first seven East-West Games. He appeared in 11 All-Star games at Comiskey Park in all, the last being at age 40 in 1946. By the time integration came to baseball, Radcliffe was too old to play.

Seventeen-year-old Connie Johnson was in his first year of professional baseball when he was selected to play in the 1940 game. He was with the Toledo Crawfords and was one of the pitchers victimized when the East scored four runs in the sixth inning en route to a 12-0 win.8 He signed with the Kansas City Monarchs the following season and was with them, except for three years in the military, through 1950, appearing in his second and last East-West Game in 1950. On August 20, 1950, he pitched the middle three innings and hit a triple at Comiskey Park. He was credited with the win as the West won 5-3. After three seasons in the minor leagues, Johnson made his major-league debut in 1953 with the Chicago White Sox.

On July 27, 1941, more than 50,000 fans came through the turnstiles, with a paid attendance figure of 47,865.9 There were a couple of new names on the East team that year, and they each contributed to an 8-3 win that gave the series lead to the East. Catcher Roy Campanella of the Baltimore Elite Giants and infielder Monte Irvin of the Newark Eagles were in the forefront as the East broke the game open with a six-run fourth inning. The big inning was topped off with a homer off the bat of Buck Leonard of the Homestead Grays.

In 1942 Campanella participated in an exhibition at Cleveland, playing for the Cincinnati Buckeyes of the Negro American League against a group of local sandlot players. He was suspended from that year’s East-West game, but Josh Gibson had returned to the Homestead Grays and was behind the plate for the East squad. Ted Radcliffe, known as “Double-Duty,” was a catcher for the West squad in 1942. It was his second appearance behind the plate in an East-West Game. He appeared in three other All-Star games as a pitcher.

Another big crowd (estimated by the Pittsburgh Courier’s Wendell Smith at 48,000)10 was on hand on August 16, 1942. The encounter was one of the harder-fought contests in the series. Through six innings, the score was 2-2. Satchel Paige entered the game in the seventh inning for the West and the East solved him for three runs during his three innings of work, winning their third straight game, 5-2, and taking a 6-4 lead in the series. The winning pitcher that day was Dave “Impo” Barnhill. Barnhill was with the New York Cubans at the time and was sold in 1949 to the New York Giants organization. Barnhill spent three seasons at Triple-A Minneapolis, but never got to pitch in the majors.

On August 1, 1943, a record crowd of 51,723 saw Satchel Paige, in his first East-West starting appearance, hold the East hitless and scoreless in the first three innings (the only batter to reach was Josh Gibson on a walk) as the West won, 2-1. In his only plate appearance, Paige doubled and left the game for a pinch-runner in the third inning. The East’s only tally came on a ninth-inning homer by Buck Leonard.

On August 13, 1944, the West beat the East 7-4. A five-run fifth-inning rally by the West was keyed by a two-run homer by catcher Ted Radcliffe. Josh Gibson of the East hit the longest shot of the day, but it was ruled a double. In the seventh inning, his 440-foot drive hit atop the public-address system in center field and bounced back on to the playing field.11 Satchel Paige did not play. He was angered that receipts from the game did not include a fair distribution to soldiers during World War II. He had promised to withdraw if management did not “give all the money, 100 per cent, to war relief.”12 Despite these statements, there were those who felt that Paige’s absence stemmed from the unwillingness of event organizers to meet his fee demands.13

Lorenzo “Piper” Davis played in his first East-West game in 1944. He was the player-manager of the Birmingham Black Barons when he made his fifth Comiskey Park East-West appearance in 1949. He was 32 at the time. In 1950 Davis was the first black player to be signed by the Red Sox. He batted .333 in 15 games at Class-A Scranton in the Eastern League but was let go by Boston after the season. He had several good seasons with the Oakland Oaks in the Pacific Coast League. From 1952 through 1954 Davis played in 416 games and batted .296. In 1953 he had 13 homers and 97 RBIs. But by then he was 35. There would be no call from the big leagues. A similar fate awaited Ray Dandridge who in 1944 was playing in this third East-West game. In 1949, at age 35, he joined the New York Giants organization and was shipped to Triple A. In four years at Minneapolis, he played in 501 games and batted .318. In 1950, at age 36, he had 36 extra-base hits and 80 RBIs. But the Giants felt he was past his prime. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1987.

Also playing in 1944 was Sam Jethroe. He had first been selected in 1942. In 1948 he signed with Brooklyn and played in their minor-league system in 1948 and 1949. The Dodgers traded Jethrow to the Boston Braves before the 1950 season and he was selected Rookie-of-the-Year in 1950.

Most of Martin Dihigo’s career was spent in the Mexican League. He played with the New York Cubans in 1935-36 and in 1945, at the age of 40, he rejoined the New York Cubans. He was selected to play in the East-West game for the first time in 1945. Everyone who saw him play marveled at his abilities and he was enshrined in Cooperstown in 1977.

Phillip J. Schupler is not known to many baseball fans. So why does his name come up here? On the eve of the 1945 East-West Game, in mid-July 1945, Schupler, a New York State Assemblyman representing part of Brooklyn, wrote to Branch Rickey of the Brooklyn Dodgers. On the heels of the Dodgers’ signing of Babe Herman, then 42, who had taken his last competitive swing in 1938, the assemblyman, whose constituency was exclusively white, wrote:

“If you are so desperate in your search for talent, I might suggest a source which would be more productive than the various homes for the aged which you have been scouting. There are many talented and able Negro ball players available who would insure the pennant for the Dodgers. You would enhance not only the efficiency and ability of the team by hiring some colored ballplayers, but that you would also increase the prestige of the Brooklyn Ball Club by showing that you relieve believe in the letter and spirit of the Ives-Quinn law (a New York law that established a State Commission Against Discrimination).”14

One week and one day after this letter appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier, the 1945 East-West Game was played at Comiskey Park. At shortstop for the West squad was Jackie Robinson of the Kansas City Monarchs.

The West took a 9-1 lead and withstood a last-inning rally by the East to win 9-6 in front of 31,714 spectators. As reported in the Chicago Tribune, “The game ended with a slick fielding play by Jackie Robinson, former UCLA football star. He went far to the left of his shortstop position to throw out Rogerio Linares.”15 At the plate, Robinson was 0-for-5. Roy Campanella, playing for the East, was 2-for-5 with two RBIs. Campy also gunned down a runner trying to steal.

Three weeks later, on August 24, the Chicago American Giants, playing at Comiskey Park, hosted the Kansas City Monarchs in the first game of a three-game series. Clyde Sukeforth of the Brooklyn Dodgers introduced himself to Jackie Robinson. On Tuesday, August 28, the Monarchs were in Davenport, Iowa. Robinson was in Brooklyn meeting with Branch Rickey. Campanella met with Rickey on October 13. The signing of Robinson was announced later in October and the signing of Campanella was announced on April 4, 1946.16

In the aftermath of the signings of Robinson and Campanella, the East-West games continued and would do so for 15 more years at Comiskey Park.

By the time of the 1946 game, only five black players had been signed to play in Organized Baseball (all by the Dodgers). The squads that played on August 18, 1946, were brimming with talent. Dan Bankhead, one heralded player, pitched three scoreless innings in the East-West Game. The next season, less than a month after he appeared in the 1947 East-West Game, he was sold to the Brooklyn Dodgers. When he made his major-league debut on August 26, 1947, he was the fifth player of color to appear in the big leagues in the twentieth century.

Against a formidable East lineup that included Josh Gibson (in his last East-West Game), Buck Leonard, and future big leaguers Larry Doby and Monte Irvin, the West prevailed 4-1, the only East run coming in the eighth inning on a fly ball by Doby. The most exciting play of the game was a double steal engineered by the West for their third run. In the fifth inning, with one out, Artie Wilson was at third and Sam Jethroe was at first. Jethroe took off for second. Catcher Josh Gibson’s throw was cut off by Silvio Garcia who was unable to throw the scurrying Wilson out at home plate.17

By the time the 1947 East-West Game was played on July 27, with the West winning for the fifth straight game, 5-2, the color line was broken but, as had been the case in 1946, the bulk of Black talent was playing in the Negro Leagues. That was beginning to change. On the eve of the 1947 game Hank Thompson and Willard Brown, who had been scheduled to play, were with the St. Louis Browns. There were far more major-league scouts and mainstream (white) newspapers at the game, which drew 48,112 spectators. New faces were on the teams that year, most notably Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso of the New York Cubans and Luis Marquez of the Homestead Grays, both of whom made it to the majors. But there was one old face. Biz Mackey managed the East team. The game was played on his 50th birthday and, for a moment the former catcher turned back the clock, inserting himself into the game as a pinch-hitter. He was intentionally walked and left the game for a pinch-runner. The pinch-runner was one of the team’s coaches, Vic Harris, who began playing professionally in 1923. Mackey was inducted at Cooperstown in 2006.

In 1948, although Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, and Satchel Paige were in the major leagues, there was still great talent on exhibit at Comiskey Park. The West won the game 3-0 and the East was limited to three hits. Buck Leonard doubled and Minnie Miñoso singled, as did newcomer Junior Gilliam, who later became a fixture with the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers.

The 1949 game was played in the aftermath of the Negro National League folding after the 1948 season. Ten teams remained playing Black baseball at the highest level, in the Negro American League, and those teams were represented when the players took to the field on August 14, 1949. By this point, more than 35 players of color were in Organized Baseball.

Comiskey Park continued to host the East-West game through 1960 with a decline in interest and talent with each passing year. Nevertheless, a new generation of black players dreamed the dream of escaping the buses and the dust and the obscurity of the fading Negro leagues. For several, minor-league ball was on the horizon. A lucky few made it to the majors, and one player would take center stage at Cooperstown.

Prior to the 1949 game, the media praised Lenny Pearson. He was a big first baseman from the Baltimore Elites. At the age of 31, he was appearing in his sixth East-West Game at Comiskey Park. In 1950 he batted .305 in 63 games at Milwaukee of the Triple-A American Association, but he never made it to the majors.

Throwing out the first pitch in 1949 was Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler. J.B. Martin said the “presence of Mr. Chandler at the contest will give added importance to the annual game. With a number of our players now going into Organized Baseball, we thought it proper and fitting to invite the commissioner to pitch the first ball.”18 Eight of the players in the game would make it to the majors.

Ralph J. Bunche, a diplomat known for his Nobel Peace Prize and his work with the United Nations, threw out the first ball in 1950 and 24,614 spectators saw the West win, 5-3. Junior Gilliam, playing in his last East-West Game, homered for the East, and future Dodgers teammate Joe Black was the starting pitcher for the East.

The 20th Annual East-West game was staged at Comiskey Park on August 17, 1952. The number of teams in the Negro American League had fallen to six, and three teams were represented on each squad. A leading vote-getter for the East squad was Henry Kimbro of the Birmingham Black Barons.19 He was appearing in his seventh East-West game, but like most of the players in the game did not possess the talent to escape the buses and dust of the Negro Leagues.20

By 1953 there were only four teams represented at Comiskey Park. Indianapolis and Birmingham supplied the East players and from Kansas City and Memphis came the West team. These two players are worth remembering.

It was the last East-West Game for Lloyd “Pepper” Bassett, the starting catcher for the West. It was his fourth appearance in an East-West Game at Comiskey park. He was 43 and had begun his professional career in 1934 with the Crescent Stars, an independent team. His next season was in the Negro National League with Philadelphia. In 1948 the then 37-year-old had been a key part of the Birmingham Black Barons squad that played in the last Negro League World Series. In 1954 he played his last season with the Detroit Stars. He never got to play a game of integrated ball.21

It was the only East-West Game for the young shortstop of the Kansas City Monarchs. A month and four days after appearing in the August 13 game at Comiskey Park, Ernie Banks made his major-league debut Chicago’s other big-league park.

In 1954 the managers were Negro League legends Oscar Charleston and Buck O’Neil. Charleston appeared in the first three East-West games and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1976. Just how good was Oscar Charleston? Here is Honus Wagner’s assessment:

“Oscar Charleston could have played on any big-league team in history if he had been given the opportunity. He could hit, run, and throw. He could do everything a great outfielder was supposed to do. I’ve seen all the great players in the many years I’ve been around, and yet to see anyone greater than Oscar Charleston.”22

Buck O’Neil played in three East-West Games at Comiskey Park and first managed the West in 1950. He managed in five games and was introduced to a new generation of fans when Ken Burns’s Baseball aired in 1994.

Francisco “Pancho” Herrera’s seventh-inning homer was the big blow, breaking the game open as the West won its fourth game in succession, 8-4. Herrera made it to the majors, starting with the Phillies.

John Kennedy played shortstop for the West team. He was named to the team in 1955 but did not play. In 1957 he broke the color barrier with the Philadelphia Phillies, playing in five games. He was the second player of color and first African-American to play for the Phillies.

“Do you mean to tell me that old string bean can still throw good enough to pitch in a big game like that?” – Casey Stengel, 1955.23

Satchel Paige first appeared in the East-West Game at Comiskey Park in 1934, hurling four shutout innings in relief for the win. After he closed out the 10-2 East win in 1936, his travels took him far and wide. He did not return to the event until 1941. He appeared in 1942 and 1943 as well, before sitting out the 1944 game. In 1955 he signed on with his former team, the Kansas City Monarchs. In the East-West Game, Paige pitched the first three innings and allowed no hits. The West defeated the East 2-0 with two seventh-inning runs.

J.C. Hartman was only 21 when he took over at shortstop in 1955. He was signed by the Cubs the next year. After a stint in the Army, he spent three years in the Cubs organization before being drafted by Houston. Midway through the 1962 season, he joined the Colt .45’s.

In 1959, the West’s starting pitcher was Willie Smith. In the game on August 9, won by the West 8-7 in 11 innings, Smith had a three-run inside-the-park homer. “Wonderful” Willie Smith was sold to the Detroit Tigers in 1960 and made it to the majors, as an outfielder, in 1963. In nine major-league seasons, he batted .248 with 46 homers and 211 RBIs.

The 1960 game was the last hurrah at Comiskey Park. The West won 8-4. It was the 18th win for the West in 28 games.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame began honoring sportswriters with the J.G. Taylor Spink Award in 1962. In 1993 it got around to honoring Wendell Smith. Two years later, they honored Sam Lacy of the Chicago Defender.

ALAN COHEN serves as vice president-treasurer of the Connecticut Smoky Joe Wood Chapter, and is datacaster for the Hartford Yard Goats, the Double-A affiliate of the Rockies. He also works as a volunteer with Children’s Reading Partners, working with at-risk elementary-school students. He has written 50 biographies for SABR’s BioProject, and has expanded his research into the Hearst Sandlot Classic (1946-1965), which launched the careers of 88 major-league players. He has four children and six grandchildren and resides in Connecticut with wife Frances and their cat, Morty.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, and was especially fortunate to have discovered accounts of the East-West Games in the Bullpen section of B-R.com. He also accessed Newspapers.com, the Chicago Tribune, and the following:

Einstein, Charles. “Major League Scouts Will Swarm on Negro Star Tilt,” Miami News, July 23, 1947: 13.

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

Washington, Chester L. Jr. “Sez Chez: East WILL Meet West,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 20, 1938: 16.

Notes

1 Wendell Smith, “Dream Game Is the No. 1 Sports Attraction,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 13, 1949: 22.

2 William G. Nunn, “ ‘Don’t Kill the Goose that Lays the Golden Egg,’ Nunn Warns Moguls; Lauds Game’s Stars,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 14, 1937: 16.

3 Wendell Smith, “The East-West Game Reaches Maturity,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 15, 1953: 14.

4 Smith, “Dream Game Is the No. 1 Sports Attraction.”

5 “Why the East-West Game Is Played in Chicago This Year,” Kansas Whip (Topeka), August 21, 1936: 7.

6 Lloyd Lewis, “Lloyd Lewis Says Negro Baseball Is Faster Than That Shown in Majors,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 27, 1938: 1, 4 (Originally appeared in the Chicago Daily News on August 22, 1938).

7 Chester L. Washington Jr., “ ‘Dream’ Teams Set for Classic,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 5, 1939: 1, 17.

8 “East’s Colored All-Stars Beat West, 12-0,” Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1940: 21.

9 Nunn, “East Crushes West Before Record Throng, 8-3: East Batters Radcliffe in Fourth to Win Ninth ‘Dream Game’ Before 47,865 in Chicago,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 2, 1941: 17.

10 Smith, “West Bows to East Before 48,000 Fans, 5-2,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 22, 1942: 16.

11 Smith, “West Bombs East in ‘Dream Game,’ 7 to 4,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 19, 1944: 12.

12 United Press, “Paige to Lead Strike if Game Isn’t Benefit,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 2, 1944: 12.

13 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 189.

14 “Assemblyman Asks Brooklyn to Hire Negro Ballplayers,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 21, 1945:12.

15 Edward Prell, “West’s Negro All-Stars Win 3d in Row, 9-6,” Chicago Tribune, July 30, 1945: 17-18.

16 Neil Lanctot, Campy: The Two Lives of Roy Campanella (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2011), 129.

17 “45,474 Fans See West Wallop East, 4-to-1,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 24, 1946: 16.

18 “Chandler to Throw Out First Ball at Negro Baseball Game,” Chicago Tribune, August 6, 1949, Part 2: 4

19 “Dream Classic Set for Chi, August 17,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 26, 1952: 16.

20 “Negro All-Stars Ready,” Hammond Times (Munster, Indiana), August 15, 1952: 18.

21 Frederick C. Bush, “Lloyd ‘Pepper’ Bassett,” in Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2017), 7-11.

22 Smith, “Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 21, 1954: 22.

23 Smith, “Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 30, 1955: 12.