April 4, 1919: Babe Ruth slugs ‘longest homer’ in spring-training game at Tampa

Plant Field was part of an athletic facility constructed in the 1890s on the grounds of the Tampa Bay Hotel and named after Henry Plant, the hotel’s owner. The City of Tampa purchased the facility in 1899 (after Plant died), and incorporated Plant Field into the newly created Florida State Fairgrounds, surrounded by a horse and automobile racetrack. It became one of the first sites in Florida to host spring-training baseball.1

Plant Field was part of an athletic facility constructed in the 1890s on the grounds of the Tampa Bay Hotel and named after Henry Plant, the hotel’s owner. The City of Tampa purchased the facility in 1899 (after Plant died), and incorporated Plant Field into the newly created Florida State Fairgrounds, surrounded by a horse and automobile racetrack. It became one of the first sites in Florida to host spring-training baseball.1

SABR member Herb Crehan wrote that after their 1918 World Series victory over the Chicago Cubs, the Boston Red Sox “pitched camp in Florida for the first time. They were enticed to Tampa by John McGraw, [manager] of the New York Giants, who recognized that emerging star Babe Ruth would draw fans to the exhibition games.”2

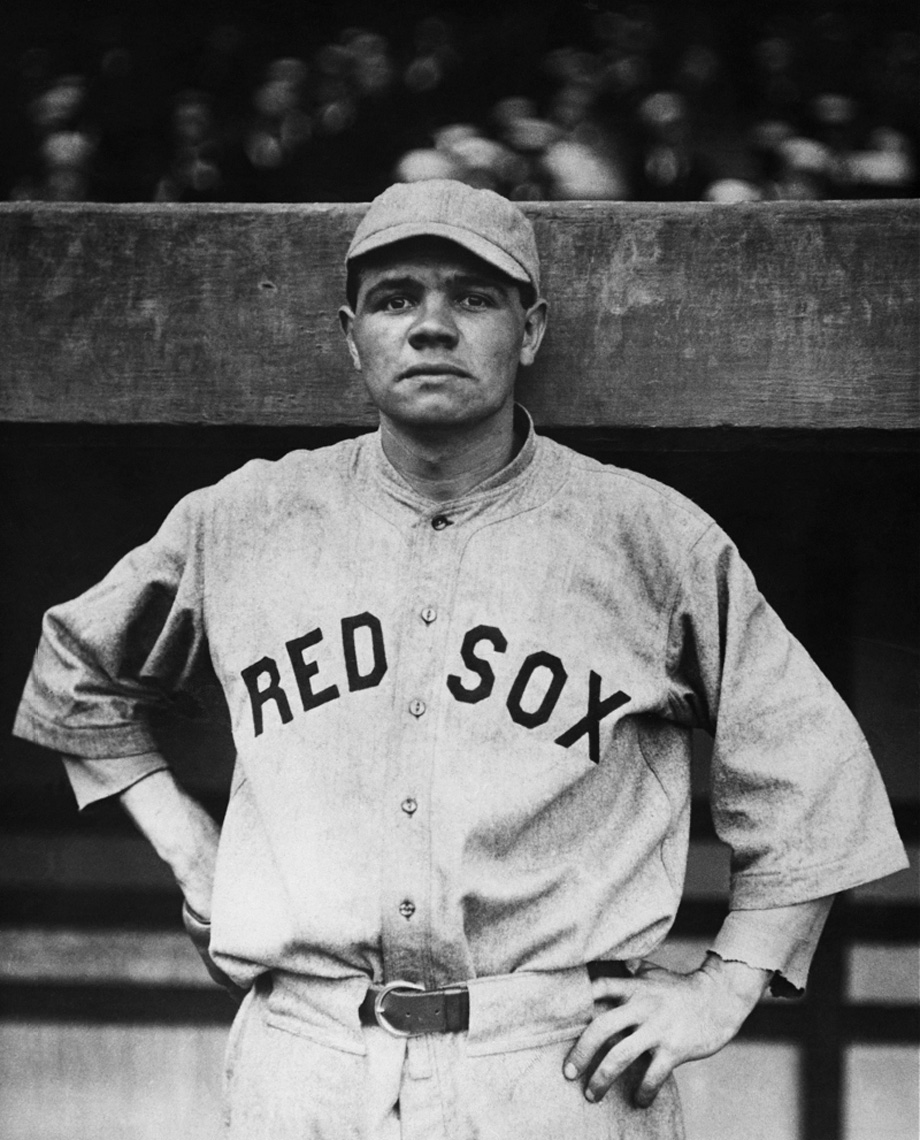

Although Ruth was gaining notoriety as a slugger in 1918 – he tied Tillie Walker of the Philadelphia Athletics for the major-league lead with 11 home runs, and his .555 slugging percentage topped the majors – he still took regular turns on the mound. During the regular season, Ruth had a 13-7 record in 20 appearances, including 19 starts. The hard-throwing lefty also won two World Series games as Boston’s starting pitcher, allowing just two runs in 17 innings. Expectations were for Ruth to become an everyday left fielder in 1919, so his bat would be in the daily lineup.

So, on April 4, 1919, a crowd of roughly 4,200, which a Tampa newspaper called “the hugest baseball gathering that has ever thronged Plant Field,”3 came out to watch Ruth’s Red Sox and McGraw’s Giants square off in the first exhibition game of the spring-training season.4 The Giants had finished second in the National League the season before but had won the pennant in 1917.

Carl Mays, who had led the majors with 30 complete games and eight shutouts in 1918, was Boston’s starting pitcher in this spring-training matchup. He had won Boston’s other two games of the 1918 World Series, including the finale. Pitching against Mays was George Smith, a right-hander who had started his career with the Giants in 1916. In 1918 he had bounced around, pitching for three teams in both starting and relief roles.5

Billy Sunday, the former major-league ballplayer turned evangelist, threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Before he became an influential preacher in the early twentieth century, Sunday had played eight seasons in the National League (1883-1890), in the outfields of the Chicago White Stockings, Allegheny City, and Philadelphia Phillies.6

The Giants’ George Burns led off the game with a walk.7 Ross Youngs followed with an infield single, but the visiting team was held off the scoreboard as the next three at-bats resulted in outs. Smith set down the Boston batters in order, and Mays returned the favor in the top of the second.

Batting cleanup and playing left field for the home team Red Sox was Ruth, called “the famous fence buster”8 by the New York Times. Leading off the bottom of the second inning, Ruth swung at a full-count Smith offering and “found it and [then] lost it in the sand back of the race track.”9 The ball sailed to direct center field, hitting the far edge of the track, and continued to roll. It finally came to rest in an open space well beyond the field’s boundaries.

McGraw told reporters, “I believe it’s the longest hit I ever saw.”10 Boston added two more tallies in the inning, staking Mays to a 3-0 lead. With two outs, Everett Scott singled and Wally Schang walked. Both scored when Mays drove a ball to right field that Youngs, trying to get Schang at third base, threw away for an error.

The Tampa Tribune reported that “Ruth’s kick took some starch out of the Giants,”11 but New York threatened in the third. With one out, Burns drew another walk. Youngs singled to left, but Ruth bobbled the ball, allowing Burns to reach third base and Youngs to take second.12 Mays retired Hal Chase – acquired in a February 1919 trade with the Cincinnati Reds after getting cleared of game-fixing allegations – on a popout and then struck out Benny Kauff.

Smith set down Dave Shean, Amos Strunk, and Ruth in order in the bottom of the inning, and then retreated to the dugout, his afternoon on the mound over.

In the top of the fourth, Mays walked Larry Doyle and Heinie Zimmerman to start the inning. Art Fletcher grounded into a force out, putting runners at the corners with one out. Lew McCarty “delivered himself of a casual wallop,”13 and Doyle scored New York’s first run. Rookie Earl Smith14 batted for George Smith and lined to center fielder Strunk, who caught the ball with a shoestring catch and threw to second to retire a tagging McCarty, while Fletcher “hardly had time to get away from third,” according to the Tampa Tribune.15

Right-handed rookie Jesse Winters came on to pitch for the Giants, and he walked the first batter he faced, Stuffy McInnis. The next two batters hit comebackers to Winter, and both also reached. Winters couldn’t handle Ossie Vitt’s hit, but he cleanly fielded Scott’s grounder. Giants third baseman Zimmerman yelled, “Third! Third!” Winters did as he was instructed, but his throw was high, and McInnis beat the throw. The Red Sox had loaded the bases with no outs. Schang drove a ball to center, deep enough for McInnis to tag and score, but Winters escaped without further damage. Boston led, 4-1.

Mays pitched a clean fifth inning, and he was replaced by Herb Pennock in the sixth.16 Winters pitched two uneventful frames in the fifth and sixth. But in the bottom of the seventh, Boston tallied again. Shean singled with two outs, and Strunk drew a walk. Winters had struck out Ruth back in the fifth (“on a beautiful drop ball,” the New York Herald reported17), but this time, according to the Tampa Tribune, “Tarzan proceeded to deliver another timely wallop.”18 Ruth’s single to right scored Shean with Boston’s fifth run.

With one out in the top of the eighth, Chase hammered a double to right-center. He moved to third on a groundout by Kauff and scored on Doyle’s single up the middle.

More excitement seemed to be saved for the ninth. Fletcher singled to start the inning for New York. After McInnis grounded out, moving Fletcher to second, Jim Thorpe – entering his last of six major-league seasons – hit for Winters.19 Thorpe hit a roller back to Pennock, who threw wildly to first. Thorpe stayed put on the overthrow, but Fletcher scored from second base. After the game, skipper McGraw told reporters that he “didn’t think his captain had that much speed.”20

Burns drew his third base on balls of the game, keeping the rally going. Pennock struck out Youngs, then walked Chase, loading the bases. The tying run was at second and the go-ahead run at first. Kauff, dubbed “The Ty Cobb of the Federal League,”21 had won batting titles when he batted .370 in 1914 and .342 in 1915, had still hit .315 in 1918 for the Giants. A single could tie the score.

But Kauff swung at the first pitch and ended the game with a weak grounder to second baseman Shean, who made the routine play. The Red Sox had won, 5-3. The Giants had left nine runners on base, the Red Sox only six.

Ruth finished the game with a 2-for-4 performance, scoring one run and driving in two. The Boston Globe also reported that Ruth “made two nice catches in [left] field, but was not quite there on ground hits.”22

If spring training was meant as a tune-up for the season, perhaps this home run was a preview for things to come in 1919. A historical marker titled “Babe’s Longest Homer” and placing the distance of the blast at 587 feet was placed on the grounds of the University of Tampa, at a spot near where the ball landed. As of the 2025 season, it was still present. According to Jeff English’s SABR biography of George Smith, “While both the distance and the claim itself remain subjects of debate, the blast might best be viewed as a preseason indicator that Ruth was about to transform the game.”23

On April 18-19, the Red Sox played a pair of spring-training games against the International League’s Baltimore Orioles. In those two contests, Ruth – a native Baltimorean and former Oriole – hit home runs in a staggering six consecutive at-bats, four in the first game and two in the second.24 This gave him at least seven homers in a two-week period.25

Ruth’s home-run clip continued into the regular season. In his first at-bat on Opening Day, April 23, he hit a first-inning, inside-the-park homer in a 10-0 rout of the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds. He went on to hit a record 29 round-trippers, thus breaking the old mark of 27, set by Ed Williamson of the NL’s Chicago White Stockings in 1884.26

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Thomas Merrick and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Photo credit: Babe Ruth, Library of Congress.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, MLB.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org. Although spring-training box scores are not available from either Baseball-Reference.com or Retrosheet.org, a box score of the game is provided:27

Notes

1 Byron Bennett, “Plant Field and the Roots of Spring Training in Tampa, Florida,” Deadball Baseball, February 21, 2015, found online at https://deadballbaseball.com/2015/02/plant-field-and-the-roots-of-spring-training-in-tampa-florida/. Accessed August 2025.

2 Herb Crehan, “Boston Red Sox Spring Training History: From 1910 to 2003,” published in Baseball Research Journal, 2003, Society for American Baseball Research, found online at https://sabr.org/journals/2003-baseball-research-journal/. Accessed September 2025. For the prior seven seasons (1912-1918), the Red Sox had camped in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

3 “Ruth Drives Giants to Defeat and Makes ’em Drink, Too, B’gads,” Tampa Tribune, April 5, 1919: 10.

4 The Boston Globe reported a crowd of 6,000. See Melville E. Webb Jr., “Sox Down Giants in First Start, Home Run Smash by Babe Ruth,” Boston Globe, April 5, 1919: 4.

5 Smith had made just two starts in 1916 and 1917 with the Giants, in a total of 23 appearances. He was purchased by the Cincinnati Reds on May 2, 1918, sold back to the Giants on June 20, and then purchased by the Brooklyn Robins on July 15. The Giants again bought him back at the end of the 1918 season. A month into the 1919 season, he was dealt from New York to the Philadelphia Phillies. His final season in the majors was 1923, and in eight total seasons, the right-hander produced a 39-81 record with a 3.89 ERA.

6 Sunday was primarily a center fielder and right fielder. He also appeared in one game as a pitcher, for Allegheny City before being traded to the Phillies on August 22, 1890, his final season. In that lone appearance, the right-hander faced two batters and allowed two hits and two earned runs, which ties him for the highest earned-run average in history.

7 Burns led the league in getting on base with a .396 on-base percentage in 1919. His 82 walks were tops, as were his 86 runs scored. In his 15-year career, Burns led the league in walks in five seasons.

8 “Giants Take Dust of Red Sox Wagon,” New York Times, April 5, 1919: 16.

9 “Great Crowd Watched Boston Defeat Giants in Fast Game,” Tampa Times, April 5, 1919: 17. The Boston Globe provided the count. See Melville E. Webb Jr., “Sox Down Giants in First Start, Home Run Smash by Babe Ruth..”

10 “Ruth Drives Giants to Defeat.”

11 “Ruth Drives Giants to Defeat.”

12 Ruth had played 47 games in 1918 as a left fielder, but in 1919, that was increased to 106 games. In 1919 Ruth led all left fielders with a .994 fielding percentage, making just one error in 162 chances.

13 “Ruth Drives Giants to Defeat.”

14 The Giants acquired Earl Smith in on January 2, 1919, in a trade with Rochester of the International League. To get the rookie, New York gave up minor leaguer Bill Kelly, future Hall of Famer Waite Hoyt, Jack Ogden, José Rodríguez, Joe Wilhoit and cash.

15 “Ruth Drives Giants to Defeat.”

16 This was Pennock’s first game since 1917. He joined the Navy in 1918 and missed that season. Frank Vaccaro, his SABR biographer, writes that Pennock had been “frustrated by six partial seasons” and that frustration led to his enlistment. See Frank Vaccaro, “Herb Pennock,” SABR Biography Project, found online at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/herb-pennock/.

17 Frederick G. Lieb, “Babe Ruth Causes Defeat of Giants by Red Sox, 5-3,” New York Herald, April 5, 1919: 15.

18 “Ruth Drives Giants to Defeat.”

19 Thorpe was often used as a pinch-hitter. In 290 games, he was used as a substitute in 132 games. In 95 plate appearances as a pinch-hitter, Thorpe batted .233.

20 “Ruth Drives Giants to Defeat.”

21 David Jones, “Benny Kauff,” SABR Biography Project, found online at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/benny-kauff/. Accessed August 2025.

22 Melville E. Webb Jr., “Sox Down Giants in First Start, Home Run Smash by Babe Ruth.” Webb inadvertently wrote “right field.”

23 Jeff English, “George Smith,” SABR Biography Project, found online at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/george-smith-2/. Accessed September 2025.

24 “Ruth Gets Six Homers for Six Successive Times at Home Plate,” Tampa Tribune, April 20, 1919: 10.

25 The author searched Florida and Boston newspapers from April 4 to April 18 and found no other mentions of Ruth hitting home runs. According to available box scores, Ruth did not homer between the game in Tampa against the Giants (April 4) and the two games against the Orioles (April 18-19).

26 Ruth broke his own major-league record three more times over the next eight seasons, clubbing 54 home runs in 1920, 59 in 1921, and 60 in 1927.

27 “Great Crowd Watched Boston Defeat Giants in Fast Game.”

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 5

New York Giants 3

Plant Field

Tampa, FL

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.