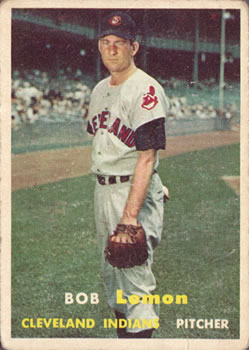

Bob Lemon

As Bob Lemon watched Willie Mays make his historic catch in Game One of the 1954 World Series against the Cleveland Indians, he may have recalled another spectacular catch by a young center fielder 8½ years earlier. That was the day, April 16, 1946, when rookie outfielder Bob Lemon saved Bob Feller’s Opening Day victory over the Chicago White Sox.

As Bob Lemon watched Willie Mays make his historic catch in Game One of the 1954 World Series against the Cleveland Indians, he may have recalled another spectacular catch by a young center fielder 8½ years earlier. That was the day, April 16, 1946, when rookie outfielder Bob Lemon saved Bob Feller’s Opening Day victory over the Chicago White Sox.

With one out and the tying run on second in the bottom of the ninth, Feller was hanging onto a 1-0 lead when Chicago pinch-hitter Jake Jones sent a drive to right-center field. Lemon, playing the right-handed batter to hit to straightaway center, sprinted to his left as the ball tailed away from him. At the last second he dove and fully stretched out his left arm to make the catch. He sprang to his feet, threw to second, and doubled off baserunner Bob Kennedy, who had already rounded third, for the final out of the game. It was Lemon’s first major-league game as an outfielder, and he sported bruises on his elbow, chin, and chest to show for his effort. Feller called it “the greatest outfield play I have ever seen.”[fn]Bob Feller, Strikeout Story (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1947), 241.[/fn]

Though he became one of the top pitchers of his era, Lemon said he would have preferred a career as an everyday player rather than as a starting pitcher with nothing to do for three out of four days. Much was made of his refusal to wear a toeplate, a standard part of a moundsman’s equipment, until well after he had become a star pitcher. But Lemon said the fact that he could make more money as a pitcher finally convinced him he should give up any thought of returning to the outfield. Still, throughout his career, he continued to work out during infield practice at third base, his position when he first came to the major leagues.

Lemon was hardheaded, but also a hard worker. Softspoken, but with a cutting wit. A devoted family man who spent long hours in bars. A power hitter in the minor leagues who couldn’t hit the changeup in the majors. A loyal friend of George Steinbrenner, but twice a victim of the dictatorial Yankee owner’s managerial ax.

Robert Granville Lemon was born in San Bernardino, California, on September 22, 1920. His father, Earl, worked for an ice company in Long Beach and operated a chicken farm. A former minor-league shortstop, Earl made sure that his son had the best baseball equipment available. His mother, Ruth, also was an avid baseball fan. In his Hall of Fame induction speech, Lemon mentioned that he had beaned his mother one day in the driveway while showing off his curveball.

Baseball was central to Bob’s life growing up in Southern California. He pitched and played the infield for Woodrow Wilson High School in Long Beach, and attracted the attention of scouts for the Cleveland Indians. After graduating, the 17-year-old Lemon signed with the Indians for $100 a month.

Although Lemon later said he was signed as a pitcher, he took the mound for only one inning in 1938 for his first team, Oswego in the Class C Canadian-American League, because the team was overloaded with pitchers. He hit .312 with seven home runs and a .450 slugging percentage in 75 games for the club, primarily as an outfielder. He also appeared in several games for Springfield (Ohio) of the Class C Middle Atlantic League.

Setting pitching aside, Lemon played shortstop and the outfield for Springfield and for New Orleans of the Southern Association the following year, combining for a .300 average in 132 games. Switching to third base in 1940, he injured his knee and struggled at the plate with Wilkes-Barre in the Class A Eastern League, but bounced back to hit .301 for the same club the following year.

Lemon got a September call-up from the Indians in 1941 and made his first major-league appearance as as a late-inning replacement for Ken Keltner at third base in a 13-7 victory over the Philadelphia Athletics on the 9th. He got his first hit three days later against Washington when he singled as a pinch-hitter against a future teammate and member of the Indians’ Big Three, the Washington Senators’ Early Wynn.

After failing to make the big-league club in spring training of 1942, Lemon was sent to the Indians’ top farm team, Baltimore of the International League, where he found his power stroke. Despite having hit only 16 home runs in his first four minor-league seasons, he was billed as a left-handed power hitter, and with the Orioles he didn’t disappoint. Lemon stroked 21 homers and drove in 80 runs during his year with the Orioles, though his batting average dropped to .268. He also impressed with his fielding at third base and started a triple play on a grounder to third on Opening Day.

While his future looked bright, the US was now at war and other duties called. Lemon enlisted in the Navy after the season and served for three years. While in the service he married Jane H. McGee on January 14, 1944, and they remained together for 56 years. They had three sons.

Lemon’s reputation as a prospect continued to spread during the war years. He starred for teams at naval bases in California and Hawaii. Other big-league players and coaches in the service got to watch Lemon hit, field, and pitch. Though he received glowing reviews for his pitching skills, his coach in Hawaii, Billy Herman, kept him in the infield because of an abundance of pitchers. As a result, in 1945 with the 14th Naval District Circuit in Hawaii, Lemon played third most of the time, tied for second in the league with 14 home runs, and was fifth in MVP balloting.

With the war over, spring training of 1946 gave the 6-foot, 170 pound, 25-year-old his first real opportunity to stick with the major-league club. Adding to his chances was the fact that incumbent third baseman Keltner, also returning from military service, was holding out and management was entertaining trade offers for him. Manager Lou Boudreau cited the young Lemon as a prime candidate if a replacement was needed at third because of his batting punch, speed, and arm.

Keltner eventually agreed to a contract and remained with the team, leaving no room at third for Lemon. In addition, it was discovered that Lemon’s fielding at the hot corner was of less than major-league quality. So Boudreau shifted him to center field to get him into the lineup. Lemon’s showing as one of the Tribe’s top hitters in the exhibition season earned him a spot in the starting lineup as the Opening Day center fielder, setting the stage for his game-saving catch to preserve Feller’s shutout.

But Lemon struggled against major-league pitching and soon lost his job in the outfield. “I could hit anything else they threw at me, but not the changeup, and the word got around pretty quick,” he said in later years. “Pretty soon that’s all I saw. Fastball out of the strike zone. Curveball out of the strike zone. Then the damned changeup.”[fn]Russell Schneider, Tales From the Tribe Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2002), 102. [/fn]

Based on reports about Lemon’s performance while pitching for Navy teams, Boudreau decided to give him serious consideration as a pitcher. In his first start, on June 3, 1946, he lasted only 3⅔ innings in a 3-2 loss to the Philadelphia A’s. Lemon showed promise the rest of the season, posting a 4-5 record and a 2.49 earned-run average in 32 appearances, including five starts, but he suffered from control problems, walking 68 and striking out only 39 in 94 innings. His .180 batting average virtually ensured that if Lemon had a future in the majors, it would be as a pitcher. After the season he joined Feller’s barnstorming team as a utilityman on a 30-game exhibition tour against Satchel Paige’s Negro All-Stars.

Still battling control problems, Lemon had a poor spring training in 1947. He was placed on waivers early in the season, but when he was claimed by Washington, the Indians decided to hold on to him and have coach Bill McKechnie help him work on his control. Although Lemon later gave credit to Mel Harder and Al Lopez, two veteran teammates in 1947, for helping him through this difficult period, McKechnie got all the plaudits when Lemon emerged as one of Cleveland’s best pitchers in the second half of the season. His mound work helped the team finish strong and move into fourth place. In 37 games, including 15 starts, he was 11-5 with a 3.44 ERA. He also batted .321 with a .607 slugging percentage.

The pennant-winning season of 1948 saw Lemon develop into a star. In spring training he introduced a “sidearm crossfire fastball” to go with his devastating curve and slider, and the hitters were mystified. Lemon and Feller led the Indians to a fast start, and both were named to the All-Star team. On June 30 Lemon tossed a 2-0 no-hitter against the Detroit Tigers, the only no-hitter of his career. Future teammate Art Houtteman was the losing pitcher.

Lemon suffered a mild concussion on July 15 when a throw by Athletics second baseman Pete Suder hit him on the head as he scored on Dale Mitchell’s double in the fifth inning. He shook it off and went back out to pitch in the sixth, but he yielded two hits and a walk, and Boudreau removed him. He then came back to pitch in relief three days later.

By September Lemon’s energy was spent and he contributed only two wins during the last month of the season. He regained his steam for the World Series, leading his team with two victories and a 1.65 ERA in 16⅓ innings as Cleveland bested the Boston Braves in six games.

Lemon was named the American League’s Outstanding Pitcher for 1948 by The Sporting News on the merits of his 20-14 record and 2.82 ERA. In his 37 starts, he tossed a league-leading 10 shutouts.

The following year, with Boudreau’s endorsement, Lemon decided to take it easy in spring training to avoid a repeat of his September slumber of the previous year. He responded with another excellent season, finishing at 22-10 with a 2.99 ERA. He also hit a career-high seven home runs. But the Indians fell to third place. Lemon now was undeniably the ace of the staff, as Feller had an off year. Lemon was only two years younger than Feller, but Rapid Robert seemed to be aging rapidly, while the younger Bob still had his best days ahead of him.

Early in 1950 Lemon reportedly told general manager Hank Greenberg that he wouldn’t take less than $50,000 for the coming season, but he came to terms in March for a salary estimated at about $35,000. The season turned out to be his busiest yet as he led the league with 37 starts, tied for the league lead with 22 complete games, relieved in seven games, and went 6-for-26 as a pinch hitter. He played in 72 games, and fatigue again plagued him in September. He upped his victory total to a league-leading 23 with 11 losses and led the league in strikeouts with 170, but his ERA climbed to 3.84. He was again named the league’s Most Outstanding Pitcher by The Sporting News. Meanwhile, the Indians dropped another notch in the standings, to fourth place.

(Late that season Indians had two Bob Lemons. They called up James Robert Lemon, a power-hitting outfielder in the minors who had been known as Bob. When he joined the Indians he asked to be called Jim. He played only briefly for Cleveland but had a 12-year career, mostly with the Washington Senators and Minnesota Twins, and hit 164 home runs.)

Al Lopez took the reins as manager of the Indians in 1951, and the team rose to second place, largely on the pitching of three 20-game winners. Lemon wasn’t one of them. Feller returned to his old form with a 22-8 record, while Mike Garcia and Wynn each won 20. Lemon struggled to 17-14 and 3.52 as a back injury in May bothered him for the rest of the season. Earlier in the year he received what he had asked for in 1950, signing for more than $50,000, which made him the highest-paid pitcher in baseball. At yearend, it was rumored that he was being offered as trade bait for Ted Williams.

Another second-place finish followed in 1952, and Lemon rebounded with a record of 22-11 and a 2.50 ERA. He led the league with 28 complete games and 310 innings pitched, and tied Garcia for the league lead with 36 starts. Wynn added 23 victories while Garcia won 22, but Feller dropped to 9-13.

Lemon was Cleveland’s only 20-game winner in 1953, but Garcia and Wynn also posted solid years and the club’s hitting improved as the Indians finished second once again. Now 32, workhorse Bob showed no signs of slowing down, again leading the league in innings pitched on his way to a 21-15, 3.36 season. On Opening Day he pitched a one-hitter and hit a home run to beat the White Sox, 6-0. By this point, he had developed a knuckleball that moved so unpredictably that the catchers couldn’t handle it, so he was afraid to use it in a game. Lopez also advised him not to use the knuckleball, saying he didn’t need it.

Before the 1954 season, a national survey of writers voted Lemon both the most conceited and the wittiest player on the Indians. During the offseason, he helped out at his father’s gas station and, later, at the ranch they bought together. He also had found time to appear in 1952 in the movie The Winning Team, which starred Ronald Reagan as Grover Cleveland Alexander. Lemon played the role of pitcher Jesse Haines and also served as Reagan’s stand-in.

Now possessing an outstanding changeup to go with his sinking fastball, amazing curve, and baffling slider, Lemon was generally considered the number-one man in Cleveland’s Big Three of Lemon, Wynn, and Garcia. “I suppose that the slider is the pitch I’ve relied on most during these last few years. I didn’t have to work to develop it, as I did to develop a good curve,” Lemon said.[fn]The Sporting News, August 18, 1954.[/fn] “I don’t try to throw a sinker. My fastball sinks naturally. I’ve always assumed my short fingers do it.”[fn]The Sporting News, September 29, 1954.[/fn]

In his prime, Lemon was remarkable in the consistency of the numbers he put up season after season – 21 to 23 wins, an ERA around 3.00 or below, and among the league leaders in starts, complete games, and innings pitched. Such was the case in 1954, as he went 23-7 with a 2.72 ERA, and led the league in complete games with 21. It was his sixth 20-win season, and for the third time he was named the American League’s Most Outstanding Pitcher by The Sporting News. “No statistic, though, could capture the man’s competitive fire, his bulldog nature that made him the Indians’ most-feared pitcher – and hard-luck first-game loser – in the World’s Series,” sportswriter Bob Broeg wrote.[fn]The Sporting News, December 15, 1954.[/fn]

In June Lemon tore a rib muscle and was out for several weeks. When he came back, he won seven straight to raise his record to 16-5. He beat the Yankees four times during the season.

Lemon was the logical choice to start Game One of the World Series against the New York Giants and he pitched a strong game through nine innings. He said the home-run pitch he threw to the Giants’ Dusty Rhodes in the tenth inning was a good one – a curveball low and slightly outside – but the lefty pinch-hitter was able to pull it just over the short right-field wall at the Polo Grounds. In an unusual public display of emotion, Lemon sailed his glove high in the air after the ball cleared the wall. A Cleveland writer quipped that the glove traveled farther than Rhodes’ homer. Coming back on two days rest for Game Four, Lemon struggled and was charged with five earned runs in four innings, giving him a 6.75 earned-run average for the Series, which the Giants swept.

Cleveland fell three games short of the Yankees in 1955 as none of the Big Three won 20, though each had a solid season. Hampered by two serious leg injuries, Lemon still recorded 18 victories, which tied him with Whitey Ford and Frank Sullivan for the most in the league. (It was the first time the American League had no 20-game winners.) Still making around $50,000, Lemon remained the highest-paid pitcher in the majors, but was only the second highest-paid Indian behind Ralph Kiner. At the end of the season, GM Greenberg proclaimed a new Big Three: Herb Score, Ray Narleski, and Don Mossi.

Lemon posted his seventh and final 20-win season in 1956, going 20-14 with a 3.03 ERA and tying Billy Pierce for the league lead in complete games with 21. Although Wynn and Score also won 20 and the Tribe pitching led the league in ERA, the team was fifth in the league in runs scored and dropped further behind the Yankees, finishing in second place, nine games back. With two months left in the season, Lemon pulled a muscle in his right thigh while reaching for a bad throw as he covered first, and the injury nagged him the rest of the way. Now almost 36 years old, he commented that while he’d pulled muscles before, “This is a new spot. It must be old age.”[fn]The Sporting News, August 15, 1956.[/fn] He recorded his 200th victory on September 11, a 3-1 win over the Orioles, and his own two-run homer, the 36th of his career, accounted for the margin of victory.

As the Indians tumbled to sixth place in 1957, Lemon had his first losing season since 1946. He finished at 6-11 with a 4.60 ERA. He had one of his best games on May 7, when he was brought in to relieve after Herb Score was felled by Gil McDougald’s line drive. Lemon pitched 8⅓ innings and gave up just six hits to claim the 2-1 victory. Lemon developed bone chips in his right elbow late in the season, but he continued to pitch.7“We were chin-high in injuries. I didn’t want to be a liability,” he said.[fn]The Sporting News, August 21, 1957.[/fn] The elbow was operated on in November, and 20 pieces of bone and tissue were removed.

Lemon struggled to recondition his arm in 1958, to no avail. He made what turned out to be his last major-league start on April 22, when he gave up five singles before leaving the game in the second inning, and he was placed on the disabled list the next day. The plan was for him to work back into shape with the San Diego farm club, but Commissioner Ford Frick, in a new strict policy to crack down on abusive practices by teams, ruled that he couldn’t work out with either the major- or the minor-league club while on the disabled list. “I’ll have to pitch to my son, Jeff, in our backyard, I guess,” Lemon said.[fn]The Sporting News, May 7, 1958.[/fn] He returned for a few more games in relief, including a game in June when he pitched five innings and said he felt pain only when he swung and missed. He finished the season in San Diego, where he was 2-5 with a 4.34 ERA in 12 games.

In 1959, the 38-year-old Lemon gave up all hopes of a comeback early in spring training and became a minor-league pitching coach for the Indians. In 1965 and 1966 he managed Seattle of the Pacific Coast League and was named Minor League Manager of the Year when he led the California Angels’ farm team to the pennant in 1966. He also coached for the Phillies (1961) and Angels (1967-68), and managed Vancouver of the PCL in 1969.

Lemon later managed in the majors for nine seasons. His managerial career followed a similar pattern everywhere he went – take on an underachieving team, lead it to success, and then get fired the next year. In 1970 he was named manager of the floundering Kansas City Royals in June 9 after serving as the team’s pitching coach. The Royals rebounded climbed to second place in the AL West in 1971, earning Lemon the Manager of the Year award. But after a disappointing fourth-place finish in 1972, he was ousted by owner Ewing Kauffman after being quoted as saying he was looking forward to retirement so he could leave baseball for some remote island. The comment most likely was tongue-in-cheek, and Lemon claimed he was misquoted. Nevertheless, Kauffman said he wanted a younger manager, and he hired Jack McKeon.

Lemon managed Sacramento of the PCL in 1974 and Richmond of the International League in 1975 before being named pitching coach for the New York Yankees in 1976. He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame that year. In his induction speech he summed up his outlook on baseball and life: “If you lose, you can’t help it. You’ve done a good job. You’ve tried the best you could. And I didn’t take it home. I would leave it at a bar on the way home someplace.”[fn]New York Times, January 13, 2000.[/fn]

Lemon got a second chance at managing in the majors when Bill Veeck hired him in 1977 to guide the Chicago White Sox, a last-place club the prior year. Again, Lemon was named Manager of the Year when he lifted the team to a surprising 90 wins and a third-place finish. But the club struggled the following year, and Veeck fired him midway through the season. That’s when Lemon ran off to join the circus. In New York the Martin-Jackson-Steinbrenner Circus was generating daily headlines. After Billy Martin made his famous remark saying of Reggie Jackson and George Steinbrenner, “One’s a born liar, the other’s convicted,” Steinbrenner forced Martin into a tearful resignation. On July 25, less than a month after he was fired by Veeck, Lemon was hired by Steinbrenner as the Yankees’ manager. In fourth place at the time Lemon took over, the Yankees surged to 48-20 the rest of the way, won a memorable one-game playoff over Boston, and defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers in six games in the World Series.

Lemon’s low-key style seemed to be just what the team needed. Outfielder Jay Johnstone said, “Lem’s sort of like an Andy Griffith character. You know, ‘Take it easy, don’t panic, we’ll think of something.’ ”[fn]New York Times, January 13, 2000.[/fn] Another Yankee player, unnamed, said, “Lem just puts you out there and lets you play. He never overmanages. If you can’t play for him, you can’t play for anybody.”[fn]The Sporting News, June 30, 1979.[/fn] But the circus continued. Only five days after Lemon was hired in 1978, an announcement was made that he would become general manager after the 1979 season and Martin would return as manager in 1980. Martin didn’t have to wait that long.

Tragedy struck the Lemon family shortly after the 1978 World Series when Bob and Jane’s youngest son, Jerry, was killed in an automobile accident. According to Steinbrenner, Lemon lost his motivation after that.

With the team suffering from injuries and off to a sluggish 34-31 start in 1979, Steinbrenner decided to pull the plug early on Lemon and replaced him with Martin. The Yankees fared slightly better under Martin, but could manage only a fourth-place finish. Lemon continued to work as a scout for the Yankees until Steinbrenner called for him once more late in the 1981 season. This time, manager Gene Michael drew Steinbrenner’s ire when he would not apologize for saying Steinbrenner was always threatening to fire him. Commenting on his decision to hire Lemon, Steinbrenner said, “He has the one quality that means so much to me, loyalty. If you needed one word to describe Bob Lemon, it would be ‘decent.’”[fn]The Sporting News, September 26, 1981.[/fn]

When he was rehired as manager, Lemon said, “When (Steinbrenner) replaced me before, it may have been more for my own good. With the problems I had, some of the incentive was lost. After he did it, he explained to me how he thought I felt. It took me a while to realize that he was right. … When I went home, I really missed (managing). It was just a case of getting myself back together.”[fn]New York Times, September 7, 1981.[/fn]

Although the team finished only 11-14 under Lemon, the Yankees earned a playoff berth in the unique strike-shortened 1981 season because of their first-place showing in the first half. They made it all the way to the World Series, but lost in six games to the Dodgers.

Lemon came under fire for some questionable moves in the Series, including lifting Tommy John for a pinch-hitter with the score tied 1-1 in the fourth inning of the final game, but the club announced that he would remain manager in 1982, with Michael returning the following year. Like Martin, Michael didn’t have to wait that long. After only 14 games and a 6-8 record in 1982, Lemon was sent back to California to return to scouting duties and Michael was named manager once again.

Lemon returned to his home in the Bixby Knolls section of Long Beach, where he had lived with his wife since 1949. He reportedly remained on the Yankees’ payroll under a lifetime contract awarded by Steinbrenner after the 1978 World Series.

The Indians retired Lemon’s number 21 in 1998. He had compiled a 207-128 record with a 3.23 ERA in 13 seasons. He was named to the American League All-Star Team each year from 1948 through 1954 and was the first manager to win a world championship after beginning the season as the manager of a different team. A left-handed batter, he was one of the best hitting pitchers ever in the majors, and his 37 home runs were one short of the record, held by Wes Ferrell.

Bob Lemon died at a nursing home January 11, 2000, at the age of 79, after several years of failing health. He was survived by his wife, Jane, and two sons, Jeff and James.

Though he was always regarded as unflappable, Lemon told a reporter late in life that he had suffered inside. “I had ulcers like everybody else,” he said.

“I’ve had a hell of a life,” Lemon said. “I’ve never looked back and regretted anything. I’ve had everything in baseball a man could ask for. I’ve been so fortunate. Outside of my boy getting killed. That really puts it into perspective. So you don’t win the pennant. You don’t win the World Series. Who gives a damn? Twenty years from now, who’ll give a damn? You do the best you can. That’s it.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

This biography is included in the book Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

The Sporting News, various issues, 1942 through 1982.

Cleveland Plain Dealer and Cleveland Press, 1946 through 1958.

Ed McAuley, Bob Lemon, the Work Horse (New York: A.S. Barnes, 1951).

New York Times, various issues, 1978 through 1982.

“Hall of Fame Pitcher Bob Lemon Takes It Easier Now,” Los Angeles Times, April 21, 1988.

Russell Schneider, Tales From the Tribe Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2002).

Baseball Hall of Fame, Bob Lemon induction speech.

The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract.

Baseball-Reference.com.

Retrosheet.org.

Wikipedia.org.

Internet Movie Database.

Full Name

Robert Granville Lemon

Born

September 22, 1920 at San Bernardino, CA (USA)

Died

January 11, 2000 at Long Beach, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.