October 5, 1934: Paul Dean impresses brother Dizzy in Cardinals’ Game 3 win

After the Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Cardinals split two contests in the Motor City, the 1934 World Series moved down into the dry, dust-beaten heartland for Game Three. It was the first postseason game in St. Louis in three years, and an opportunity for those in the Midwest — far removed from the cluster of big-league teams found on the Eastern Seaboard — to witness baseball’s ultimate battle.

After the Detroit Tigers and St. Louis Cardinals split two contests in the Motor City, the 1934 World Series moved down into the dry, dust-beaten heartland for Game Three. It was the first postseason game in St. Louis in three years, and an opportunity for those in the Midwest — far removed from the cluster of big-league teams found on the Eastern Seaboard — to witness baseball’s ultimate battle.

“When the World Series comes to town,” Westbrook Pegler observed in covering the scene for the Chicago Daily News, “there is a stirring and churning through the cotton belt and the southwest, and up they come … the knowing, critical gaze of the most expert class of customers in the country … the nuts from the true baseball country where the ball players are raised for the big city trade.”1

Many had lined up outside the ballpark for hours, hoping to buy any remaining tickets. They had arrived from the distant hinterlands in any manner they could — as hitchhikers, as stowaways jumping onto open train boxcars, or by packing into the back of a flatbed jalopy.

“There were wide hats in the audience,” noticed Pegler during the day, “and the high and whiny voice of the Texas and Oklahoma trade was heard in the uproar. … Arkansas too, and rural Missouri and little towns in Tennessee and Mississippi, where nothing much happens and a World Series within driving distance is not to be missed. … There is a long spell between planting and picking when there isn’t much to do but play ball or go to minor league games. You can’t hurry cotton.”2

It was indeed a pilgrimage for these fans, as they had also come to watch one of their own ply his trade.

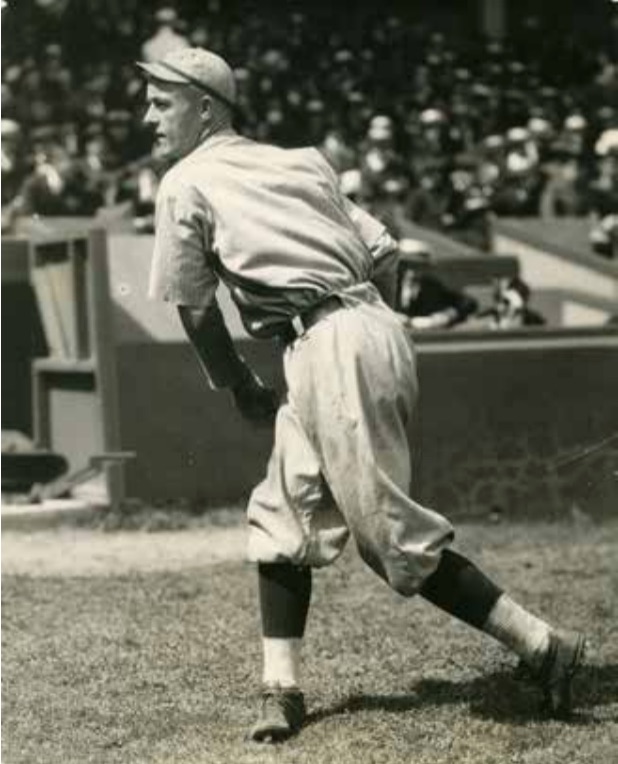

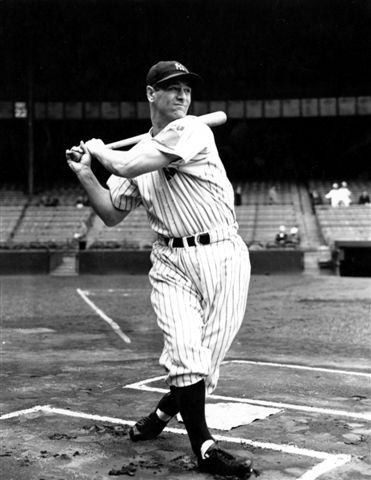

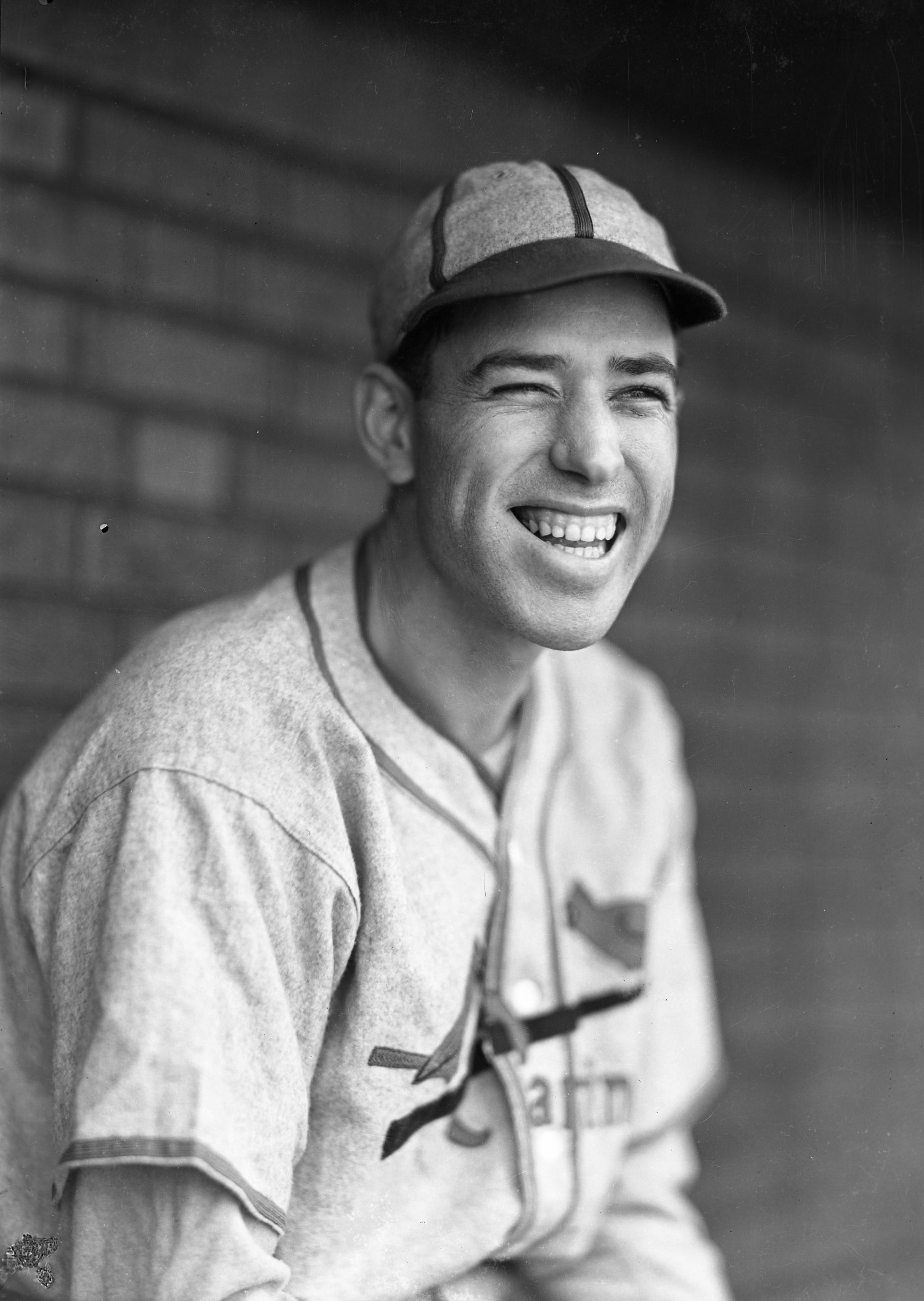

With the remainder of the Series yet to unfold, the game would perhaps be the capstone moment in the magnificent rookie season of 22-year-old pitcher Paul Dean, himself a sharecropper in the Arkansas cotton fields before entering professional baseball three years earlier.

Before he had even taken his first jog in spring training for the Cardinals in Bradenton back in February, Dean was already being promoted for a salary increase by his famous older brother Jay, who was better known as Dizzy. For the sake of alliteration, sportswriters had planted the nickname of Daffy on Paul; but in reality he was inward and quiet, and let his sibling do the talking.

After a rough start to the season, Paul found a groove and crafted a 2.70 ERA in the month of August, followed by a 1.93 mark in September. By season’s end he had posted a record of 19-11 and notched 5.79 strikeouts per nine innings, the best ratio in baseball. Paul had been nearly as dominant as Dizzy in the second half of the schedule — his high point a no-hitter against the Dodgers in Brooklyn on September 21, which immediately followed a three-hit shutout Diz had authored in the opener of a doubleheader that day. Paul had also logged an impressive six wins in seven decisions against the defending World Series champions, the New York Giants — including three victories over legendary hurler Carl Hubbell.

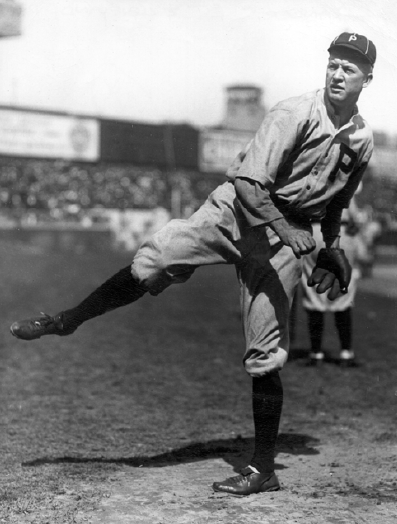

None of Paul’s regular-season laurels now mattered, however, as his ultimate test stood before him. In being handed the ball by manager Frankie Frisch in the pivotal third game, Paul would go up against curveball artist Tommy Bridges of the Tigers. Bridges had won five of his last six starts in September, and had won 22 games during the season for Detroit — second only to Schoolboy Rowe (24) on the team — while pacing the Tigers with 275 innings pitched and 151 strikeouts.

Even though his club had beaten Cardinals pitchers Bill Hallahan and Bill Walker in an extra-inning affair in Game Two, Detroit player-manager Mickey Cochrane was scratching his head in mapping out a solution for the Series with the brothers lurking. “For always there are the Deans to taunt them,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch beat writer J. Roy Stockton noted colorfully, “two lanky, steel-armed pitching devils, sinister figures in American League eyes, ubiquitous and stalking, ready and certain to enter the fray when the need arises.”3

The thermometer recorded an unseasonably warm temperature of 77 degrees at Dean’s first pitch at 3:00 P.M., as 34,073 had crammed into the edifice at Grand and Dodier. It was the first time Paul had taken the mound in six days, while Bridges had last pitched five days earlier when he threw four no-hit innings against the St. Louis Browns in Detroit before Cochrane pulled him to rest his arm.

Charlie Gehringer singled after Paul retired the first two batters, but Hank Greenberg, one of baseball’s top run producers, popped to catcher Bill DeLancey to end the inning. It was the first of many Tigers assaults Dean would need to sidestep.

The Cards scored in each of the first two innings on a pair of sacrifice flies — the first by Jack Rothrock after leadoff batter Pepper Martin had tripled, and the second by Dean himself to drive in Rip Collins. St. Louis extended its lead to 4-0 in the fifth inning, as Martin again started things with “a double against the chicken wire in right field” before Rothrock tripled him home.4 Frisch followed with a single to score Rothrock, a blow that sent Bridges out of the game.

“Elon] Hogsett walked slowly into the box,” Pegler recounted the situation as the relief pitcher entered with nobody out, “surveyed a gloomy situation calmly, and flexed his left arm with a few practice shots at Cochrane’s mitt.”5 Hogsett immediately induced Joe Medwick to hit into the first Detroit double play of the series. He next got a hand from Cochrane, who threw out Collins trying to steal after normally surehanded shortstop Billy Rogell committed his first of two errors in the game. Collins was one of three Gas House Gang members Cochrane would nab on the bases during the afternoon to help keep the Tigers close.

All the while, Paul bent but did not break, permitting baserunners in every Detroit frame until he finally enjoyed a one-two-three inning in the seventh — and again in the eighth. And though Paul frequently got into trouble, Frisch never lost faith as “Dizzy was down in the bullpen warming up just for exercise in the eighth and ninth innings.”6

The Tigers threatened again in the ninth, breaking up the shutout bid when Greenberg drove a long triple to center field with two out, sending home speedster Jo-Jo White from first. But Paul refocused, getting Goose Goslin on a popup to Frisch at second to end the game and put the Cardinals ahead in the Series two games to one. Martin, Frisch, and Collins each stroked two hits to lead the Cardinals attack while DeLancey contributed a double. The frustrated Tigers stranded 13 runners and left the bases loaded twice.

“As the game ended, Brother Dizzy slung his sweater over his shoulder and walked up fast, shouldering ball players, customers, and policemen aside to intercept Daffy at the lip of the Cardinals’ dugout,” Pegler wrote. “He placed his left hand on Daffy’s shoulder, looked him dead in the eye, and solemnly acknowledged that next to his older brother, Daffy was the best pitcher in the world.”7 And while still alive in the series, the Tigers appeared to be a beaten team. “They have the look of losers,” Pegler asserted, “whereas the Deans are overbearing even when mediocre.”8

In the home clubhouse, Paul’s teammates surrounded him in appreciation once again. “Dean sat in front of his locker, declaring he was never so tired in his life,” reported Charles Dunkley of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. “He was dripping with perspiration and puffing like a racehorse.”9 When asked to speak, Paul uttered a simple respect for the Tigers’ bats. “They didn’t give me much trouble. I was faster the last two innings than at any time during the game. I don’t hold no ballclub cheap, and that’s the reason I beared down.”10

After Paul’s win in Game Three, a car with New York license plates approached Dizzy outside the ballpark. The occupants offered him a ride home — which he accepted. Although Diz arrived safely, the incident prompted Cardinals owner Sam Breadon to provide the Deans with armed guards for the remainder of the World Series, in fear of their being kidnapped or extorted by gamblers.

“Shucks, nobody’s going to kidnap me. Not in this town,” Dizzy scoffed. “Even if they did, that wouldn’t do Detroit no good, ‘less’n they took Paul too, and I guess two Deans would be more than they could handle.”11

So it would be for the Tigers.

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed below, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and SABR.org

Notes

1 Westbrook Pegler, “Cards Take Game Three,” Chicago Daily News, October 6, 1934: 3C.

2 Ibid.

3 J. Roy Stockton, “Carleton Pitches for Cards Today, Auker for Tigers,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 6, 1934: 1.

4 Westbrook Pegler, “Cards Take Game Three,” Chicago Daily News, October 6, 1934: 3C.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Charles Dunkley, “Dean Stands Tall,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 6, 1934: 5.

10 Ibid.

11 J. Roy Stockton, “Dizzy Too Friendly, Is Put Under Guard,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 6, 1934: 1.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Cardinals 4

Detroit Tigers 1

Game 3, WS

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.