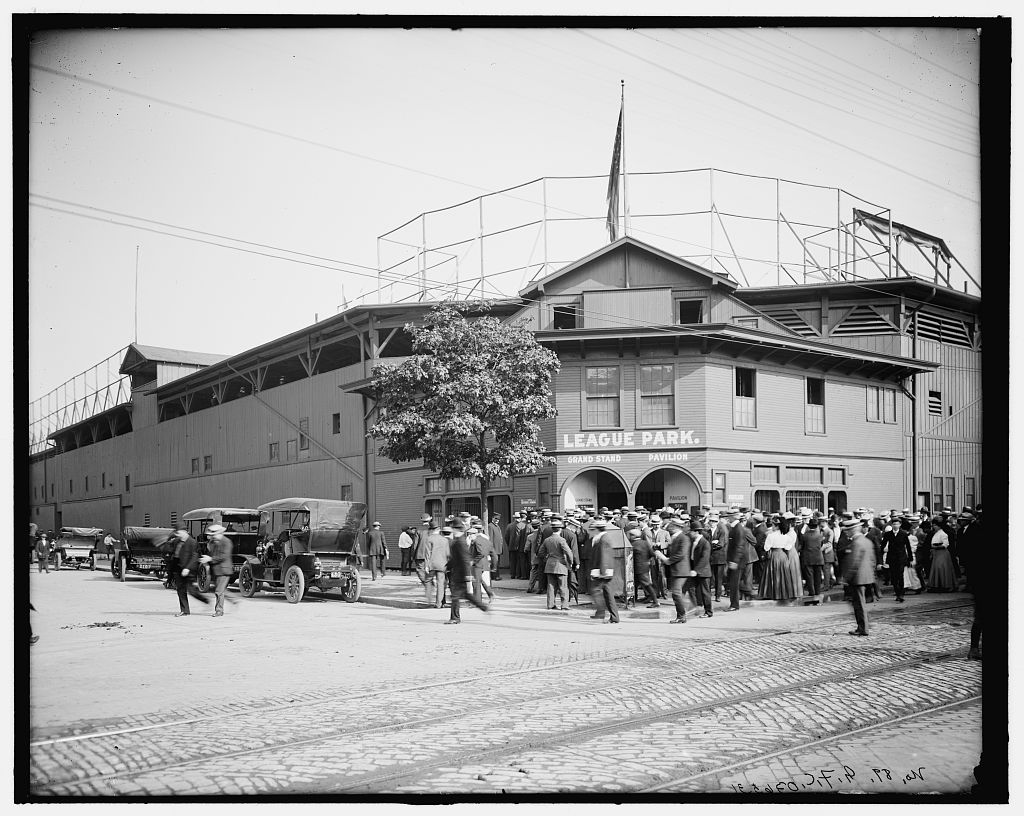

League Park (Cleveland)

This article was written by Bill Johnson

The 1931 opening of Cleveland Stadium, also known as Cleveland Municipal Stadium, was celebrated by both the team and the entire region as a portent of expansion. Expansion of the commercial hub’s national reputation, expansion of the economic opportunity for northeastern Ohio, expansion of the national pastime into an arena that could accommodate more paid customers than any other baseball stadium in the nation, and expansion of the Cleveland Indians to the metropolitan downtown area, also created a scheduling quandary. The new park was enormous, capable of holding more than 70,000 fans, but the historical baseball headquarters of the city stood three miles away, in the shape of League Park, built in 1891 at the corner of Dunham Street (later East 66th) and Lexington Avenue. (It took its name from National League Park, at Cedar Avenue and East 49th, which had been the home field for the Cleveland Spiders between 1879 and 1884.)

In the 1880s Cleveland was a city on the ascent. Home to luminaries like John D. Rockefeller, and host to a burgeoning port industry on Lake Erie, the expanding metropolis was served by several trolley companies competing for riders in the city’s eastern expansion. In 1887, as part of a court settlement resulting from a skirmish among rival rail firms, Frank DeHaas Robison, owner of the Cleveland City Railway Company, was awarded part-ownership of the Cleveland Forest Citys, an American Association team. In 1889 Robison’s team joined the National League, was rechristened the Spiders, and played in a ballpark at Euclid and Payne Avenues. A gifted businessman and opportunist, Robison and his brother Stanley elected to build a baseball park at their trolley stop at East 66th Street and Lexington Avenue, and move the team from Euclid and Payne, in an attempt to grow both ballpark attendance and trolley ridership.

On May 1, 1891, at just after 4 P.M., Cy Young opened the Cleveland Spiders’ National League season against Cincinnati and, in doing so, consecrated the new League Park (now referred to as League Park I, it was actually the third park called “League”). The game was a sellout, and the Spiders won, 12-3. The 9,000-seat facility, a wooden structure largely filled with simple benches, hosted the Spiders for 10 years. Because of a zoning requirement that it fit within the existing neighborhood street geometry (the field was originally built around a saloon and two other houses whose owners refused to sell their land when the park was conceived), League was oddly shaped. It boasted a 353-foot left-field line but a right-field fence that, a mere 290 feet from home plate, seemingly abutted the infield grass. There was also very little foul territory, so the fans were almost in the midst of the action.

After the team’s dismal 20-win season (and miserable home attendance of 6,088) in 1899, the franchise was one of four teams removed from the National League, and Robison sold the club to John Kilfoyl and Charles Somers. In 1900, the minor-league Cleveland Lake Shores played at League Park and in 1901 the new Cleveland Blues franchise became one of Ban Johnson’s original eight American League teams and moved into the facility.

The Blues opened the 1901 inaugural season on April 29 with a 4-3 win over the Milwaukee Brewers (the following season, 1902, the Brewers relocated relocate to St Louis and renamed themselves the Browns). When Nap Lajoie joined the Blues in the middle of the 1902 season, attendance surged and allowed the franchise and ballpark to become more firmly established.

In 1903 the Indians added bleachers in front of the right-field fence and stands in left field outside the playing field. The right-field bleachers were gone by 1908. The park saw two no-hitters toward the end of that season: by Bob Rhoads against the Boston Red Sox on September 18, and the perfect game tossed by Addie Joss against the White Sox on October 2. In 1909 Cy Young returned to the club and, after drawing an impressive 422,000 spectators, the team, now called the Naps in honor of Lajoie, decided to expand the field after the season.

Osborn Engineering, a noted designer of ballparks, was contracted to make the ballpark safer, more spacious, and generally more accommodating to paying customers. On April 21, 1910, the new and improved League Park (II) reopened, capable of accommodating up to 24,414 fans. The business offices were located upstairs, above the ticket office, and were as cramped as the bullpens, which were wedged between the foul lines and bleachers in right and left fields (the Indians used the first-base side).

The western dimension, the right-field line, was built along East 66th Street, while left field ran along Linwood Avenue. In the outfield, the east face from left field to center field was bordered by East 70th Street. Still only 290 feet down the right-field line (240 feet if roped off for big games), it expanded in a rectangle to a farthest reach of 460 feet just left of straightaway center field (this was shortened to 420 feet in a 1920 renovation). The left-field line extended 375 feet at the pole.

The concrete and steel ballparks that were built starting in the early 20th century to replace the older wooden ones (largely fire hazards like League I) are now collectively referred to as Jewel Box ballparks. Philadelphia was home to the progenitor of the class, Baker Bowl (1895), as well as one of the early, true Jewel Boxes at Shibe Park (1909). With the exceptions of Fenway Park in Boston and Wrigley Field in Chicago, the Jewel Box parks have been consigned to history. Except for Shibe and Comiskey (Chicago), the Jewel Boxes were all built amid the physical limitations of existing city blocks, which resulted in similarly quirky, asymmetrical outfields.

In 1910 baseball suffered the tragic death of Joss at the age of 31. The next year, on July 24, 1911, the team hosted a benefit fundraiser for the family of their deceased pitcher. The all-star contest, featuring players like Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker, raised well over $12,000 for the Joss family, all from admission fees ranging between 25 cents and $1.

The team changed its name to the Indians in 1915, and, from 1916 to 1927, as a perquisite of owning the team, Jim Dunn changed the name of League Park to Dunn Field. It remained so appointed until Alva Bradley bought the team from the Dunn estate in 1927 and restored the name League Park.

During the Dunn era, the Indians brought the city a World Series title (1920). Game Five, at League Park, produced three historic World Series firsts: Bill Wambsganss recorded what remains the only unassisted triple play; Jim Bagby became the first pitcher to hit a home run in a World Series; and Elmer Smith tagged the Brooklyn Robins’ Burleigh Grimes for the first grand slam in the major-league postseason.

In 1920 the park underwent a partial renovation as dimensions were changed slightly by the addition of outfield bleachers and a 40-foot wall was erected along the right-field boundary. Prevailing winds tended to carry batted balls to left, but even with strong gusts of wind it was difficult to knock the ball out of the yard.

The right-field fence, if not truly monstrous, was at least odd. The first 20 feet above the ground were solid wall, and on top of that was a 25-foot-tall wire mesh fence with steel stanchions along the border. In all, the fence was 45 feet high, in contrast with Fenway Park’s left-field “Green Monster,” which rises 37 feet. In 1934, perhaps because of the proclivities of young left-handed slugger Hal Trosky, the screen was lowered five feet, leaving the barrier an even 40 feet high. A ball hitting the fence at League might have hit the solid wall and bounced predictably; it might have struck the chicken-wire mesh and died; or it might have hit a stanchion and bounced in any direction. There are numerous anecdotes of balls that hit the fence less than a foot apart, one falling limply to the ground after hitting the mesh, and the next bouncing almost all the way back to second base in a ricochet off one of the metal posts.

On July 7, 1923, the Indians scored 27 runs against the Red Sox, setting the American League record for the most runs in a nine-inning game. Also that year, Walter Johnson logged his 3,000th career strikeout, and in 1925 Tris Speaker knocked his 3,000th hit.

The field had no permanent lights, so night games were not an option, but there was one such contest there, on July 27, 1931. Using a portable lighting system borrowed from the Kansas City Monarchs, the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League played the barnstorming House of David in the first (and only) night contest at League.

The final significant event at the ballpark occurred on July 16, 1941, when Joe DiMaggio hit safely in his 56th consecutive game. The streak was broken the next day, at Municipal Stadium.

The 1946 season marked the beginning of the end for League Park. The most notable baseball milestone at the park that year was Ted Williams’ only career inside-the-park home run, which gave a pennant-clinching win to the Red Sox. In 1932 the Indians seeking to draw larger crowds, had begun experimenting with their schedule by playing night, holiday, and weekend games at the larger Cleveland Stadium in 1932. That experiment was conducted intermittently throughout the 1930s, until owner Alva Bradley finally settled on a semipredictable split of games between the two stadiums that was used until September 21, 1946. On that date the Indians and the Detroit Tigers closed out both the season and the baseball life of League Park. Tigers pitcher Dizzy Trout defeated Joe Berry and the Indians 5-3 in 11 innings before only 2,772 spectators. The venue had become the smallest ballpark in the American League, and when Bill Veeck bought the Indians in 1946, he shifted the schedule to Municipal Stadium on a full-time basis.

From 1943 to 1949, the park was used by the Negro American League Cleveland Buckeyes. That 1945 Buckeyes season opened with a doubleheader sweep of the Memphis Red Sox, which Cleveland followed with sweeps against the Chicago American Giants and the Kansas City Monarchs. By early September, the Buckeyes sat atop the Negro American League standings, and when league executives chose to cancel the NAL championship series, Cleveland was simply awarded the pennant and a shot at the NNL champion Homestead Grays. Playing, and winning, two of the four home games of that Negro World Series at League, the Buckeyes went on to capture their only Negro World Series. It marked only the second baseball championship in the city’s history.1

League Park was also used by the Cleveland Rams of the National Football League between 1936 and 1945, and by the Cleveland Browns of the nascent All-American Football Conference from 1946 to 1950. The Indians eventually sold the park to the city of Cleveland, which demolished most of the facility in 1951. The city left only the structure along the right-field line, including a ticket window, to mark an open city park.

Most of the articles and retrospectives concerning League Park – at least those written between 1960 and 2000 – began with some form of commentary on the state of the neighborhood of Lexington Avenue and East 66th Street. It had become, to be charitable, rough. What was the site of Babe Ruth’s 500th home run (off Cleveland’s Willis Hudlin in 1929) had become a slum. In 2002, as part of an ongoing effort to revitalize the area, the last of the grandstand structure was demolished in an attempted upgrade, leaving one less tangible trace of the ballpark’s existence.

Fortunately, a steward of Cleveland’s past and future emerged in the early 21st century. In 2014, the Baseball Heritage Museum moved into the old League Park clubhouse, welcoming new fans in to learn about the glory days of the stadium, and helping to save the site in the form of a public recreation facility. Osborn Engineering, the firm that managed the 1910 refurbishment, provided design work for a League Park III. As of 2024, the tiny park at East 66th and Lexington lives again.2

Photo credit

League Park, Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Co. Collection.

Sources

Baseball Reference.com (http://www.baseball-reference.com).

Cleveland News (various issues 1933-1941).

Cleveland Plain Dealer (various issues 1933-1941).

Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. Available online: [http://ech.cwru.edu/ech-cgi/article.pl?id=RFDH

Jedlick, P. League Park (Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research, 1990).

League Park Society, online: [http://www.leaguepark.org

Lewis, Franklin, The Cleveland Indians (New York: Putnam and Sons, 1949).

Lowry, Philip. Green Cathedrals (New York: Walker Publishing Company, 2006).

Schneider, Russ. The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia, 3rd ed. (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2004).

Notes

1 This information, verified in newspapers of the day, was contributed by Ken Krsolovic and Bryan Fritz, authors of League Park: Historic Home of Cleveland Baseball, 1891-1946 (McFarland & Co., 2013)

2 As of early 2025, the Baseball Heritage Museum may be visited at: https://baseballheritagemuseum.org/