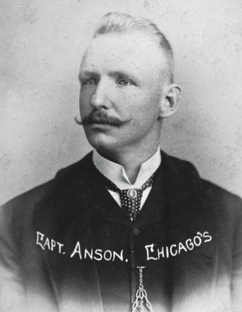

Cap Anson

Cap Anson, baseball’s first superstar, was the dominant on-field figure of nineteenth-century baseball. He was a small-town boy from Iowa who earned his fame as the playing manager of the fabled Chicago White Stockings, the National League team now known as the Cubs. A larger-than-life figure of great talents and great faults, Anson managed the White Stockings to five pennants and set all the batting records that men such as Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth later broke. Anson was the second manager (after Harry Wright) to win 1,000 games and the first player to stroke 3,000 hits (though his exact total varies from one source to another). Although he retired from active play in 1897, he is still the all-time leader in hits, runs scored, doubles, and runs batted in for the Chicago franchise.

Cap Anson, baseball’s first superstar, was the dominant on-field figure of nineteenth-century baseball. He was a small-town boy from Iowa who earned his fame as the playing manager of the fabled Chicago White Stockings, the National League team now known as the Cubs. A larger-than-life figure of great talents and great faults, Anson managed the White Stockings to five pennants and set all the batting records that men such as Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth later broke. Anson was the second manager (after Harry Wright) to win 1,000 games and the first player to stroke 3,000 hits (though his exact total varies from one source to another). Although he retired from active play in 1897, he is still the all-time leader in hits, runs scored, doubles, and runs batted in for the Chicago franchise.

Adrian Constantine Anson, named after two towns in southern Michigan that his father admired, was born in a log cabin in Marshall (later Marshalltown), Iowa, on April 17, 1852. Adrian was the youngest son of Henry and Jeannette Rice Anson, and was the first pioneer child born in the town that his father had founded. Henry Anson, who was born in New York State and had drifted westward as a young adult, was a surveyor, land agent, and businessman who brought his wife and oldest son Sturgis to Iowa in a covered wagon. He found a promising valley in the center of the state, built a log cabin, and laid out a main street. Henry worked tirelessly to build and promote Marshalltown, and is recognized to this day as the patriarch of the city. Jeannette Anson was a sturdy pioneer housewife who died when Adrian was seven years of age, leaving behind an all-male household.

Adrian, whose family proudly claimed descent from the British naval hero Lord Anson, was a strong, strapping boy with reddish hair and a self-admitted aversion to schoolwork and chores. Not until his teenage years, when baseball fever swept through Marshalltown, did Adrian find an acceptable outlet for his energy and enthusiasm. He practiced diligently and earned a place on the town team, the Marshalltown Stars, at the age of 15. The Stars, with Henry Anson at third base, Adrian’s brother Sturgis in center field, and Adrian at second base, won the Iowa state championship in 1868.

Henry Anson enrolled his sons in a preparatory course at the College of Notre Dame for two years beginning in 1865, but Adrian was more interested in baseball and skating than in his studies. A later sojourn at the state college in Iowa City (now the University of Iowa) ended similarly. Young Adrian Anson wanted to play professional ball, and his break came in 1870 when the famous Rockford Forest City club and its star pitcher, Al Spalding, came to Marshalltown for a pair of games. The Forest City team won both matches, but the Anson clan played so impressively that the Rockford management sent contract offers to all three of the Ansons. Henry and Sturgis turned Rockford down, but Adrian accepted and joined the Forest City squad in the spring of 1871.

The 19-year-old Adrian, dubbed “The Marshalltown Infant,” batted .325 for Rockford and established himself as one of the stars of the new National Association. The last-place Rockford team disbanded at season’s end, but the pennant-winning Philadelphia Athletics quickly signed Adrian to a contract. He rewarded the Athletics with a .415 average in 1872, third best in the Association. He played third base for the Athletics that season, but spent the next three seasons shuttling from first to third base with occasional stops at second, shortstop, catcher, and the outfield. The hard-hitting utility man quickly became one of Philadelphia’s most popular athletes.

Boston Red Stockings manager Harry Wright had always dreamed of introducing baseball to England, his home country, and in 1874 Wright and his star pitcher Al Spalding organized a mid-season trip to England. The Red Stockings and the Philadelphia Athletics took a three-week respite from National Association play and sailed to the Old World, where they played both baseball and cricket for British crowds. Adrian Anson led all the players on both teams in batting during the tour, and, more importantly, began a friendship with Spalding. Both were young men from the Midwest, less than two years apart in age, and both had willed themselves to prominence in the baseball profession. Each found reasons to admire the other, and their relationship would play an important role in Anson’s life for the next 30 years.

During the 1875 season, Chicago club president William Hulbert signed four of Boston’s brightest stars, including pitcher Al Spalding, to play for his White Stockings in the new National League in 1876. Spalding recommended that Hulbert also sign two Philadelphia standouts, Ezra Sutton and Adrian Anson. Sutton and Anson reached agreements with Hulbert, though Sutton later reneged on his deal and returned to the Athletics. Anson moved to Chicago in early 1876, and the White Stockings, managed by Spalding and powered by Anson and batting champ Ross Barnes, won the first National League pennant that year.

On a personal note, Anson began dating Virginia Fiegal, daughter of a saloon owner, during his Philadelphia days. He met Virginia when he was 20 and she only 13 or 14, though this was not considered unusual at the time. Their relationship hit a roadblock after Adrian signed his contract with Chicago, when Virginia strongly objected to Adrian’s desire to leave Philadelphia. Anson was no contract-jumper, so he offered William Hulbert $1,000 to buy his way out of the agreement. Hulbert refused, and Anson, unwilling to break his contract and not wanting to lose Virginia, asked Virginia’s father for his daughter’s hand in marriage. Adrian and Virginia were wed in November 1876 and started a family that eventually produced four daughters, all of whom grew to adulthood, and three sons who died in infancy.

Adrian Anson, powerfully built at 6-feet-2 and over 200 pounds, was the biggest and strongest man in the game during the 1870s. Some reports state that he did not take a full swing at the plate; instead, he pushed his bat at the ball and relied upon his strong arms and wrists to produce line drives. An outstanding place hitter, Anson and the White Stockings worked an early version of the hit-and-run play to perfection. So good was Anson’s bat control that he struck out only once during the 1878 season and twice in 1879. He also served as Spalding’s assistant on the field, enthusiastically cheering his teammates and arguing with opponents and umpires. Anson had managed the Philadelphia Athletics for the last few weeks of the 1875 season, and looked forward to the day that he would succeed Spalding as leader of the White Stockings.

The Chicago team failed to repeat as champions under Spalding in 1877. Spalding then moved into the club presidency, but passed over Anson and appointed Bob Ferguson as his successor. Ferguson’s regime was a failure, and Spalding named Anson as captain and manager for the 1879 season. He was now “Cap” Anson, and in one of his first decisions, the former utility man planted himself at first base and remained there for the rest of his career. His 1879 team challenged for the pennant, but fell apart after Anson was sidelined due to illness in late August. However, Anson’s 1880 White Stockings, fortified by newcomers such as catcher Mike Kelly, pitcher Larry Corcoran, and outfielders George Gore and Abner Dalrymple, won the flag with a .798 winning percentage, the highest in league history.

Two more pennants followed in 1881 and 1882 as Anson, who won the batting title in 1881 with a .399 mark, cemented his stature as the hardest hitter and finest field general in the game. He used his foghorn voice and belligerent manner to rile opponents and frighten umpires, and made himself the focus of attention in nearly every game he played. His outbursts against the intimidated umpires earned him the title “King of Kickers.” His White Stockings followed Anson’s lead and played a hustling, battling brand of ball that won no friends in other league cities, but put Chicago on the top of the baseball world. As baseball grew in popularity, the handsome and highly successful Cap Anson became the sport’s first true national celebrity.

Regrettably, Anson used his stature to drive minority players from the game. An 1883 exhibition game in Toledo, Ohio, between the local team and the White Stockings nearly ended before it began when Anson angrily refused to take the field against Toledo’s African-American catcher, Moses Fleetwood Walker. Faced with the loss of gate receipts, Anson relented after a loud protest, but his bellicose attitude made Anson, wittingly or not, the acknowledged leader of the segregation forces already at work in the game. Other players and managers followed Anson’s lead, and similar incidents occurred with regularity for the rest of the decade. In 1887, Anson made headlines again when he refused to play an exhibition in Newark unless the local club removed its African-American battery, catcher Walker and pitcher George Stovey, from the field. Teams and leagues began to bar minorities from participation, and by the early 1890s, no black players remained in the professional ranks.

Chicago was the highest-scoring team in baseball, and Anson, as its cleanup hitter, was the leading run producer in the game. The Chicago Tribune introduced a new statistic, runs batted in, in 1880 and reported that Cap Anson led the league in this category by a healthy margin. The statistic was soon dropped, but later researchers have determined that Anson led the National League in RBIs eight times. He is credited with driving in more than 2,000 runs, behind only Henry Aaron and Babe Ruth on the all-time list despite the fact that National League teams played fewer than 100 games per season for much of Anson’s career.

Anson hit more than 12 homers in a season only once. He swatted 21 round-trippers in 1884 by taking advantage of the tiny Chicago ballpark, which featured a left-field fence only 180 feet from home plate (balls hit over the fence had been ruled as doubles in previous seasons). On August 5 and 6, 1884, Anson belted five homers in two games, a record that has been tied (by Stan Musial, among others) but never broken. However, Anson drove in most of his runs with sharp line drives that the barehanded infielders found nearly impossible to stop. Fielding gloves found their way into the National League by the mid-1880s, but Anson’s production continued uninterrupted. He batted .300 or better in each of his first 20 professional seasons, and by 1886 he was baseball’s all-time leader in games played, runs, hits, RBIs, and several other categories.

He was less successful as a fielder, leading the league in errors several times and setting the all-time career mark for miscues by a first baseman. However, Anson was fearless in stopping hard-thrown balls with his bare hands, and his size made him an excellent target for his infield mates. He was an integral part of the celebrated “Stonewall Infield” with third-baseman Tom Burns, shortstop Ed Williamson, and second-baseman Fred Pfeffer. This unit remained together for seven seasons, from 1883 to 1889, and formed the backbone of the Chicago defense.

Anson had been a teetotaler since his younger days, but his White Stockings were a hard-drinking crew that kept their captain up nights with their behavior. His 1883 and 1884 teams failed to win the pennant, partially due to off-the-field controversies, but in 1885 the White Stockings reclaimed their place at the top of the league. New pitcher John Clarkson posted a 53-16 record and led the team to the pennant after a spirited race against the New York Giants. However, Anson’s team played poorly in a postseason “World’s Series” against the St. Louis Browns of the American Association. The series ended, officially, in a tie after a disputed Browns victory caused no end of controversy. In 1886 Anson drove in 147 runs in 125 games and led the White Stockings to the pennant once again, but his charges lost the six-game World’s Series against the Browns when some of the Chicago players appeared to be inebriated on the field.

Spalding and Anson decided to break up the team, selling Mike Kelly to Boston for a then-record $10,000 and dropping veterans George Gore and Abner Dalrymple, among others. The 1887 squad was a better-behaved bunch, but finished in third place despite Anson’s outstanding performance at bat. The 35-year-old captain won the batting title with a career-best .421 in a year in which walks counted as hits (though later researchers removed the 60 walks from his hit totals, leaving his average at .347 and giving the title to Detroit’s Sam Thompson). In early 1888 Spalding sold John Clarkson, baseball’s best pitcher, to Boston for $10,000. Several new men tried, and failed, to fill Clarkson’s shoes, and the White Stockings finished second despite another batting championship by Anson.

After the 1888 season Spalding, owner of the sporting goods company that still bears his name, took the Chicago club and a team of National League all-stars on a ballplaying excursion around the world. Virginia Anson accompanied the party as Anson directed the White Stockings in New Zealand, Australia, Ceylon, Egypt, and the European continent. The trip lost money for its backers, including Anson, but it introduced baseball (and advertised Spalding’s business) to countries that had never seen the sport before. The six-month adventure was the high point of Cap Anson’s life, and takes up nearly half of Anson’s autobiography, published in 1900. At the conclusion of the trip, in April of 1889, Spalding signed Anson to an unprecedented 10-year contract as player and manager of the White Stockings.

By 1890, Anson was a stockholder in the Chicago ballclub, owning 13 percent of the team. A company man through and through, he bitterly criticized the Brotherhood of Professional Ball Players, whose members quit the National League en masse in early 1890 and formed the Players League. Anson, one of a handful of stars who refused to jump to the new league, hastily assembled a new group of youngsters (which the newspapers dubbed Anson’s Colts) and finished second that year. Spalding worked behind the scenes to undermine the rival circuit, while Anson led the charge in the newspapers, denouncing the jumpers as “traitors” and gleefully predicting the eventual failure of the upstart league. The new circuit collapsed after one season, but Anson’s role in the defeat angered many of his former players.

Some reporters called Anson “the man who saved the National League,” but many former Players Leaguers hated the Chicago captain for his attitude toward them. Such stars as Hugh Duffy and George Van Haltren refused to return to Chicago after the collapse of the rival circuit, costing Anson much-needed talent. In 1891, Anson’s Colts held first place until mid-September, but an 18-game winning streak vaulted Boston into the lead amid rumors that Boston opponents threw games to keep the pennant out of Anson’s hands. Chicago finished in second place, and Cap Anson believed for the rest of his life that he lost the championship through the machinations of his former Players League rivals.

Anson, after more than 20 years as a player, began to slow down. His average dipped below .300 for the first time in 1891, though he led the league once again in runs batted in with 120. He had never been a great fielder, but covered so little ground at first base that the pitcher and second baseman had to help out on balls hit to the right side. As stubborn as ever, Anson was the last bare-handed first baseman in the major leagues, finally donning a glove in 1892. At bat, Anson produced one last hurrah with a remarkable .388 average in 1894 at the age of 42, but his slowness on the basepaths bogged down the Chicago offense. As a manager, his increasing strictness and inflexibility angered his charges. He was baseball’s biggest celebrity, even enjoying a run as an actor on Broadway in a play called A Runaway Colt in December of 1895, but his Colts fell steadily in the standings.

His position as manager was weakened in 1891 when Al Spalding stepped down as team president. Anson might have been willing to retire from the field and accept the position, but Spalding, who retained controlling ownership in the team, appointed former Boston manager Jim Hart to the post. Anson held little regard for Hart, who had served Spalding as business manager of the round-the-world tour four years before, and the two men clashed often over personnel and disciplinary matters during the next several seasons.

Spalding and Hart reorganized the club in 1892, and Anson signed a new contract with the Chicago ballclub. This agreement retained Anson’s 13 percent stake in the team, but cut one year off his previous 10-year pact, though Anson claimed that he did not discover the discrepancy until later. At any rate, the new agreement expired on February 1, 1898. Anson, who by 1894 was the oldest player in the league, stubbornly kept himself in the lineup despite his dwindling production and his deteriorating relationships with Hart and the Chicago players. He batted .285 in 1897, a respectable figure today but well below the league average, and his Colts finished in ninth place. Spalding and Hart declined to renew his contract, and after 27 seasons, Cap Anson’s career was over. The 45-year-old Anson retired as baseball’s all-time leader in games played, times at bat, runs, hits, doubles, runs batted in, and wins as a manager.

Spalding offered to hold a testimonial benefit for Anson and raise $50,000 as a going-away gift, but Anson proudly turned it down, explaining that accepting such an offer would “stultify my manhood” and smacked of charity. The former Chicago captain then accepted a position as manager of the New York Giants, succeeding Bill Joyce, who had been sharply criticized by the national press for his part in an ugly on-field brawl. Giants owner Andrew Freedman promised Anson full control of the team, but continually interfered with personnel and management issues. He also ignored Anson’s request to trade or release Joyce, who remained on the team and retained the allegiance of many of the players. Anson led the Giants to a 9-13 record before Freedman fired him and reinstated Joyce after the controversy over the brawl died down.

After his humiliating exit from the Giants, Anson tried to obtain a Western League franchise and move it to the South Side of Chicago, but Spalding, whose approval for the move was necessary under to rules of the National Agreement, refused permission. This act ended the decades-long friendship between the two men. Anson then served as president of a revived American Association, which attempted to begin play in 1900 but folded due to financial pressures. After this defeat, Anson expressed his bitterness in his autobiography, A Ball Player’s Career. “Baseball as at present conducted is a gigantic monopoly,” stated Anson, “intolerant of opposition, and run on a grab-all-that-there-is-in-sight basis that is alienating its friends and disgusting the very public that has so long and cheerfully given to it the support that it has withheld from other forms of amusement.”

Cap Anson was finished with the National League, and although he lived for another two decades, he would never again hold any official position in organized ball. Instead, Anson opened a bowling and billiards emporium in downtown Chicago and served as a vice-president of the new American Bowling Congress. He captained a team that won the ABC five-man national title in 1904, making Anson one of the few men in history to win championships in more than one sport. He then turned his energies to what appeared to be a promising political career. Elected to a term as Chicago city clerk in 1905, Anson soon became embroiled in numerous controversies that he was, by personality and temperament, unable to overcome. He lost a bid for renomination, and his career in public office ended ignominiously. His bowling and billiards business floundered, and in late 1905 the cash-strapped Anson sold his remaining stock in the Chicago ballclub and severed his 29-year connection with the team.

He then devoted himself to semipro ball, investing most of his remaining money in his own team (called Anson’s Colts) and building his own ballpark on the South Side. This effort was a money-loser, and in desperation Anson donned a uniform in 1908 and played first base at the age of 56. He could still hit, but was nearly immobile in the field, and his Colts finished in the middle of the City League standings for three seasons. In those years, Anson played many games against the Chicago Leland Giants, the leading African-American team of the era, without apparent complaint. Anson, his finances stretched to the limit, sold his team after the 1909 season and returned to the stage. He created a monologue and performed it in vaudeville houses throughout the Midwest for the next few years.

Anson’s later life was filled with disappointment. The National League offered to provide a pension for the ex-ballplayer, but Anson stoutly refused all offers of assistance. He declared bankruptcy in 1910, and by 1913 he had lost his home and moved in with a daughter and son-in-law. Virginia Anson died in 1915 after a long illness, and the widowed ex-ballplayer resumed his stage career in a skit written by his friend Ring Lardner titled “First Aid for Father.” The skit starred Anson and his daughters Adele and Dorothy, and the Anson clan crisscrossed the nation, sharing bills with jugglers and animal acts in small town and big city alike. Vaudeville allowed Anson to support himself, but barely, and he retired, penniless, from the stage in 1921. He died on April 14, 1922, three days shy of his 70th birthday, and was buried in Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago. The National League paid his funeral expenses. Seventeen years later, on May 2, 1939, Anson and his former friend and mentor Al Spalding were named to the Baseball Hall of Fame by a special committee.

A version of this biography is included in “Nuclear Powered Baseball: Articles Inspired by The Simpsons Episode Homer At the Bat” (SABR, 2016), edited by Emily Hawks and Bill Nowlin. For more information, click here.

Sources

Books

Anson, Adrian C. A Ball Player’s Career (Chicago: Era Publishing, 1900).

Brown, Warren. The Chicago Cubs (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1946).

Levine, Peter. A. G. Spalding and the Rise of Baseball: The Promise of American Sport (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Spalding, Albert G. Base Ball: America’s National Game (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1911).

Zang, David W. Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995).

Newspapers and Magazines

Chicago Tribune, The Sporting News, Baseball Magazine, Sporting Life, and The New York Times for the 1870-1920 period.

Full Name

Adrian Constantine Anson

Born

April 17, 1852 at Marshalltown, IA (USA)

Died

April 14, 1922 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.