Charlie Finley

He owned and operated the Kansas City and Oakland Athletics for 20 years. Nearly everyone, including fellow owners, players, the fans of his teams, the media, and the baseball commissioner, disliked or even despised him. When his team lost, he blamed everyone but himself. When they won, he was apt to call the radio booth during the game if his name was not mentioned often enough. He was a self-made millionaire who, in the words of sportswriter Jim Murray, “worshipped his creator.”1

He owned and operated the Kansas City and Oakland Athletics for 20 years. Nearly everyone, including fellow owners, players, the fans of his teams, the media, and the baseball commissioner, disliked or even despised him. When his team lost, he blamed everyone but himself. When they won, he was apt to call the radio booth during the game if his name was not mentioned often enough. He was a self-made millionaire who, in the words of sportswriter Jim Murray, “worshipped his creator.”1

Working at a time when baseball abhorred change of any stripe, Charlie Finley had more ideas and imagination than all his fellow owners put together. Tactless, rude, and vulgar, he could outwork everyone, running his insurance company in Chicago while badgering his baseball employees at long distance. Working in an age before cellular telephones, Finley spent hours on the phone, usually with someone who would rather have been doing anything other than talking to Charlie. He was a professional salesman, and worked his fellow owners by browbeating them until they might finally give in. Most of the crazy ideas he advanced — orange baseballs and bases — never caught on, but a few that did — World Series night games, the designated hitter — changed the game forever.

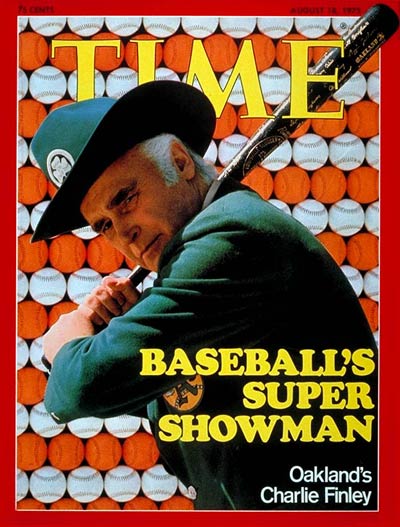

It is impossible to write about the great 1970s Athletics, a team that won three consecutive World Series titles, without presenting Finley as the star of the show; the baseball team, even the games themselves, often seemed a sidelight to some other story. This is exactly how Finley wanted it. Ron Bergman, who covered the Oakland Athletics for the Oakland Tribune, once wrote, “Finley makes the games incidental. After the 1973 Series was over … I had to go back and read about the games to see what happened.”2 Several books were written about the A’s during their glory years, and every one of them placed Finley front and center.

Finley ran the entire operation to an extent that was startling. He not only made all the baseball decisions in Oakland — deciding whom to draft or sign, making trades, suggesting the lineup, advising in-game strategy — he often wrote the copy for the yearbook, made out the song lists for the organist, decided the menu for the press room during the World Series, and designed the uniforms. Finley had to approve all injuries before a player could be put on the disabled list. Not surprisingly, he went through office staffers at an alarming rate. People soon tire of being screamed at, humiliated, and treated, as one former employee put it, “worse than animals.”

And yet he won. And what’s more, Finley won almost entirely with players that his organization had signed and developed. The Athletics were built precisely the way we imagine a great team ought to be built: They signed or drafted dozens of quality players, sifted through them for a few years until several developed, made a couple of key trades to redistribute the talent, and provided depth with veteran role players. It worked splendidly, and likely would have continued to work splendidly had the game’s labor system not changed. Once the players had to be treated on nearly equal ground, Finley’s techniques were no longer successful. For this, Finley had himself to blame, for no one did more to incite the player revolution than Charlie.

If the architect of the great Athletics had been anyone other than Finley, he might have received a book contract, and spent his retirement years giving speeches on college campuses. Since it was Finley, everyone could hardly wait until he got out of baseball so that they could unplug their noses. It is amusing to imagine what the other owners must have felt watching this man hoist the World Series trophy every year on national television.

Charles Oscar Finley was born on February 22, 1918, just outside Birmingham, in an area that is now incorporated as Ensley, Alabama. Randolph Finley, Charles’s grandfather had come to the area from Ireland and worked in the steel mills. He and Emma Caroline Finley raised 11 children, one of whom, Oscar, was Charles’s father. Emma Fields, Charles’s mother, came from Georgia originally, but her family made it to Birmingham when she was a child. Oscar met Emma when he was working as an apprentice at the steel mill. They soon married, settled in a residential neighborhood, and were very active in the Baptist Church.

Oscar and Emma had three children: Thelma, Charles, and Fred. Charles, the middle child, was an extraordinary businessman even as a youngster. By the age of 12 he mowed lawns six days a week, eventually hiring and organizing a crew of people. He sold newspapers and magazines all over Birmingham, with his mother driving the car. He sold eggs. He made and sold cheap wine during the Prohibition era. He was also the batboy for the Birmingham Barons, and he loved the game, playing it whenever he could.

In 1933 the steel mills began laying people off, so Oscar moved his family to Gary, Indiana. In his new city Charlie quickly found ways to make money, working, always working. He didn’t just play baseball — he organized his own team and found a sponsor. After graduating from Mann High School in 1936, he worked in a steel mill for five years. Laid off in 1941, and classified as 4-F for induction into the service, he went to work in an ordnance plant east of Gary in LaPorte, Indiana. That same year he married Shirley McCartney, a local woman from a well-respected and well-to-do family. He remained employed at the plant until 1946.

In the meantime Finley began selling insurance on the side, and he was so good at it that he left his job and began working for a Travelers agent in Gary. He set sales records for the company that held until the 1960s. Ironically, the one person he forgot to insure was himself, and this mistake nearly ruined everything. A severe bout of tuberculosis hospitalized him for 2½ years and nearly cost him his life. Typically, he spent all of this idle time planning his next move. He developed a plan to sell life insurance to doctors and surgeons. When he left the hospital, he started his own company, and it quickly became one of the largest insurance carriers in the country. Within a few years he was a multimillionaire.

Finley was also a lifelong baseball nut, playing on lots of local organized teams before his illness. Once he became rich, he spent several years attempting to buy a major-league team. He first tried to purchase the Philadelphia Athletics from the Mack family in 1953, and was later a spurned bidder for the Tigers, the White Sox, and the expansion Los Angeles Angels. Finally, in December 1960 he bought a controlling interest in the Kansas City Athletics from the estate of Arnold Johnson, and within a few months he had bought out all of the other investors. The club he bought had been terrible for many years, and had finished in last place, 39 games behind the Yankees, in 1960.

Finley’s first baseball move was to hire “Trader” Frank Lane to run the team, a sure sign that he wanted a quick fix. Early in the season, Finley overruled a few of Lane’s moves, and it was soon apparent who was running the show. Though working under an eight-year contract, Lane did not make it through his first season. Calling Finley a liar and “an egotist,” he later went to court to get some of the money Finley owed him. The man who “replaced” Lane was Pat Friday, who also worked for Finley in his insurance company. Within a few years, Finley’s front office consisted mainly of his wife, Shirley, his cousin Carl Finley, and his son, Charles Jr. The traveling secretary was apt to be a college intern.

Finley’s first manager was Joe Gordon, who once reportedly handed the home-plate umpire a lineup card that was inscribed: “Approved by C.O.F.”3 Gordon lasted 60 games. When Finley decided to hire his right fielder as the new manager, he instructed the P.A. announcer to call out: “Hank Bauer, your playing days are over. You have been named manager of the Kansas City A’s.” Bauer trotted in to the dugout.

Finley quickly concluded that he understood the game better than anyone else. One classic example involved promising outfielder Manny Jiménez. In July 1962, Manny, a 22-year-old rookie, was hitting .337 with 10 home runs. When asked about his rising star, Finley snapped, “I don’t pay Jiménez to hit singles.” He ordered Bauer to get him to swing for the fences: “Get that smart Cuban in your office, and get another Cuban to interpret and bang your fist on the desk. We’ll see what happens.”4 What happened was that Jiménez, who was not Cuban at all but Dominican, hit .301, but with only one home run for the rest of year, and showed up in 1963 without a starting job.

Finley spent a lot of time complaining about the city and the ballpark and trying to move the team. In his first few years in Kansas City he publicly courted the communities of Atlanta, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Oakland, and several times sought league permission to move. In January 1964 Finley signed a lease with the state of Kentucky to use Fairgrounds Stadium in Louisville. Unfortunately, he failed to notify the American League. Ten days later, the league voted 9 to 1 against the shift, and gave Finley until February 1 to conclude a lease in Kansas City.

Finley remained undeterred. He flew to Oakland, signed a letter of intent to move his team there, and told the league he would sign no more than a two-year lease in Kansas City. In an emergency league meeting, the owners voted 9 to 1 that the lease being offered by Kansas City was fair and reasonable and called another meeting to consider expelling Finley from the league. He finally gave in and signed an ironclad four-year lease to keep the Athletics in Kansas City through 1967.

When he first acquired the team, Finley tried anything and everything to interest people in his team: cow-milking contests, greased-pig contests, a sheep pasture (with a shepherd) beyond right field, a zoo beyond left. He installed a mechanical rabbit named Harvey behind home plate to pop up and hand the umpire new baseballs. He had “Little Blowhard,” a compressed-air device inside of home plate that blew dirt away. He hired Miss U.S.A to be the batgirl. He installed a yellow cab to bring in pitchers from the bullpen. He released helium balloons with A’s tickets throughout the countryside. He installed lights in the dugout so that the fans could see the manager and players discussing strategy. He shot off fireworks in the park, but the neighbors complained and the city made him desist. Finley sued the city.

During Finley’s early tenure in Kansas City, the team received a lot of attention for its uniforms, for which the owner himself, of course, selected the design. Finley first introduced the sleeveless top to the American League in 1962, and the following year he shocked baseball traditionalists by dressing his team head-to-toe in yellow with green trim. The Athletics’ lone All-Star Game representative in 1963, Norm Siebern, did not play in the game, reportedly because manager Ralph Houk thought that the Athletics uniform was a disgrace to the American League. In 1966 the team added “kangaroo white” shoes to its ensemble.

The one thing Finley promised the good people of Kansas City that he actually delivered on might have been the biggest long shot: He got the Beatles to play at Municipal Stadium. The 1964 tour, their first in North America, was already ongoing when (after several attempts) he lured the biggest sensation in pop music history for $150,000 — at the time the largest fee ever paid for a music concert.

In 1965 Finley introduced the baseball world to his new mascot, a Missouri mule, predictably named Charlie O. Not only did the mule have its own pen just outside the park, it also went on a few road trips and stayed in the team’s hotel. In Yankee Stadium, Finley got Ken Harrelson to ride Charlie O., and the frightened mule ran around trying to buck him off. Only the Chicago White Sox did not let Charlie O. on the field, so Finley arranged a protest rally across the street from Comiskey Park with pretty models and a six-piece band, which played appropriate tunes, like “Mule Train.” One afternoon in Kansas City, he led the mule onto the field through the center-field fence before realizing that the game had already started.

In late 1965 he signed the 59-year-old Satchel Paige to start a game against the Red Sox in Kansas City. Allowing only a single to Carl Yastrzemski, Paige threw three shutout innings. Soon thereafter, Bert Campaneris played all nine positions in a game, before finally leaving in the ninth inning when, while playing catcher, he was involved in a collision at home plate. After the season, coach Whitey Herzog had seen enough: “This is nothing more than a damned sideshow. Winning over here is a joke.”5

Despite all of these early efforts at promotion, the Athletics had miserable attendance throughout Finley’s years in Kansas City. In 1960, the year before Finley bought the team, the Athletics drew only 774,944 fans. This was a modest total, even for the time, but it was more than Finley ever attracted in any of his seven years in Kansas City. In 1965 the team attracted only 528,344 admissions. In their first season in 1969, the Kansas City Royals easily surpassed Finley’s highest attendance figure.

Finley was also full of bright ideas to improve the game. He wanted interleague play and realignment to promote geographic rivalries. He pushed for World Series and All-Star Games at night. He wanted the season shortened. He cajoled for the adoption of a designated hitter for the pitcher. He proposed a designated runner, who could freely pinch-run for a player any time he got on without replacing him in the lineup. He tried to get the owners to adopt a three-ball walk and actually used the rule in one preseason game in 1971. (There were 19 walks in the game, and it was not tried again.) He pushed to have active players made eligible for the Hall of Fame. He installed a clock in the scoreboard to enforce a long ignored rule that mandated no more than twenty seconds between pitches.

Finley continually tried to add elements of color to the game. His first year in Kansas City, he painted the box seats and the outfield fences citrus yellow and the foul poles fluorescent pink. At the league meetings in 1970, Finley proposed colored bases and colored foul lines, and the A’s received permission to use gold bases for their home opener. A few years later, he pushed for orange baseballs, which he carried with him everywhere he went. He even received permission to use the balls in a spring-training game. About this time most tennis organizations began using a yellow ball, and one cannot help but think that the orange baseball might have caught on if Finley had not been the author of the idea.

Finley continually tried to add elements of color to the game. His first year in Kansas City, he painted the box seats and the outfield fences citrus yellow and the foul poles fluorescent pink. At the league meetings in 1970, Finley proposed colored bases and colored foul lines, and the A’s received permission to use gold bases for their home opener. A few years later, he pushed for orange baseballs, which he carried with him everywhere he went. He even received permission to use the balls in a spring-training game. About this time most tennis organizations began using a yellow ball, and one cannot help but think that the orange baseball might have caught on if Finley had not been the author of the idea.

Finley once offered the following advice to a hypothetical man thinking of becoming a baseball owner: “Do not go into any league meeting looking alert and awake; slump down like you’ve been out all night and keep your eyes half closed, and when it is your turn to vote you ask to pass. Then you wait and see how the others vote, and you vote the same way. Suggest no innovations. Make no efforts at change. That way you will be very popular with your fellow owners.”6

After being forced to sign his lease in early 1964, Finley essentially stopped trying to promote the team. Ernie Mehl wrote in the Kansas City Star, “Had the ownership made a deliberate attempt to sabotage a baseball organization, it could not have succeeded as well. … It is somewhat the sensation one has in walking through a hall of mirrors designed to distort, where nothing is normal, where everything appears out of focus.”7 Finley responded by staging “Ernie Mehl Appreciation Day” and planned to present Mehl with a “poison pen.” When Mehl did not attend, Finley arranged to have a truck circle the park with a caricature of Mehl dipping his pen in “poison ink.”

Star reporter Joe McGuff wrote a letter to the American League offices claiming: “Finley has done nothing to promote the season ticket sale. He has never had one salesman on the street. The A’s do not have a ticket outlet outside of Greater Kansas City.”8 Finley ignored booster clubs. He gave no support to local groups that organized ticket-buying programs. He made only cursory attempts at selling radio and TV rights. He decided that the city did not care about him so, by God, he was not going to care about the city.

Finley constantly fiddled with the dimensions of his ballpark, until it reached the point of absurdity. His first year he thought the Kansas City pitchers needed help, so he moved the left field fence back 40 feet. By 1964 he had determined that the Yankees won every year not because of their great talent, but because of the dimensions of their ballpark: deep in most of left and center fields with a short distance in right. Finley decided to make his right-field configuration identical to that in Yankee Stadium.

Unfortunately for Finley, as of 1958 the rules decreed a minimum distance of 325 feet down the foul lines with the exception of those parks already with shorter dimensions. Never one to be put off by something as silly as the rules of the game, Finley ordered that his fence conform to the Yankee Stadium dimensions from center field to right field until it reached a point five feet from the foul line and 296 feet from home plate (the Yankee Stadium distance). From there, the fence angled sharply back out so that it was exactly 325 feet away when it reached the foul line. He thus neatly skirted the rule, which stipulated the distances only on the foul line, not the distance five feet from the line. He painted “KC pennant porch” on the new fence (which was exactly 44 inches high, as it was in Yankee Stadium).

After two exhibition games, American League President Joe Cronin told Finley that all of the fence must be at least 325 feet from the plate. Finley moved the fence back to 325, changed the sign to say “One-Half Pennant Porch” and painted a line on the field that represented the Yankee Stadium dimensions. He then ordered the public address announcer to call out, “That would have been a home run at Yankee Stadium” for every fly ball that went past this line.9

This was no joke to Finley. He was apoplectic about the Yankees, and believed the rules were deliberately stacked so that they won the pennant every year. Before its reconstruction in 1974-75, Yankee Stadium had monuments for Miller Huggins, Lou Gehrig, and Babe Ruth in deep left-center field. Finley threatened to put a statue of Connie Mack right in the middle of center field, saying: “They let the Yankees have their monuments out in the playing area, but if I put one up they’ll probably try to run me out of baseball.”10

In the meantime, Finley traded for Rocky Colavito and Jim Gentile to hit home runs over his new fences. This strategy sort of worked in that the team finished third in the league with 166 home runs, including 34 by Colavito and 28 by Gentile. But Kansas City pitchers allowed 220 home runs, a major-league record that lasted until 1987. The 1964 Athletics finished last with a record of 57-105.

The next year, Finley moved the fence back, put a 40-foot screen above it and got rid of Colavito and Gentile. These actions suggest a management that does not have any idea what it is doing. Just as the pitchers and hitters begin to figure out how best to deal with the dimensions of the park, the next year they come back and have to learn all over again. In 1965 the Athletics remained in last place, with a record of 59-103. The screen stayed, and Municipal Stadium remained a pitcher’s park as long as the A’s stayed there.

Although Finley likely never relinquished the idea of leaving Kansas City once his four-year lease expired, there was nothing much for him to do about it in the meantime. He could now concentrate all of his considerable energies on a different task — signing players for his team. From 1964 to 1966, Finley invested perhaps $2 million in 200 players. This group included three future members of the Baseball Hall of Fame (Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Rollie Fingers, and Reggie Jackson) and several other future All-Stars (Rick Monday, Joe Rudi, Gene Tenace, John “Blue Moon” Odom, and Sal Bando). With all these players in place, the team began to get better.

The 1966 team won 74 games, their best showing in Kansas City. Their rise was highlighted in a spring 1967 cover story in Sports Illustrated predicting great things ahead, perhaps as soon as that season. It did not happen that quickly, and the 1967 season was marred by a bizarre player revolt.

On August 3, 1967, the Athletics returned home from Boston on a commercial flight, and a few players got a little rowdy. A couple of weeks later Finley, who had not been present, investigated briefly and fined and suspended pitcher Lew Krausse. Krausse was known as something of a drinker and was certainly in the middle of whatever happened, but according to his teammates there was no particular reason for singling him out. The players backed Krausse and issued a joint statement suggesting that the event had been blown out of proportion and blaming the whole episode on Finley’s “go betweens.”

Finley did not like back talk, especially from the hired help, and things deteriorated quickly from there. He first demanded that the players publicly retract their statement, which they refused to do. Inevitably, Finley fired manager Alvin Dark, who knew about the players’ statement and had failed to forewarn his boss about it. Ken Harrelson was quoted referring to Finley as a “menace to baseball.”11 Finley responded by giving Harrelson, one of the better players on the team, his unconditional release. The Hawk turned his freedom into a $75,000 contract with the pennant-bound Boston Red Sox. The ramifications of Harrelson’s free agency so disturbed major-league owners that they amended the rules so that, in the future, a released player had to pass through waivers before becoming a free agent.

The surviving players sought and received a hearing with Commissioner William Eckert, causing Finley to threaten retribution against those who planned to participate. The players contacted Marvin Miller, the new head of the Major League Players Association, who subsequently filed an unfair labor practice charge with the National Labor Relations Board. On September 11 there was a 14-hour meeting with the commissioner, and Finley agreed to back down in exchange for the players dropping the charge. It eventually all blew over, but this proved a watershed event. From this point forward, whenever the players union needed a symbolic bogeyman, Charlie Finley was generally around to stand in.

Finley’s four-year lease at Municipal Stadium ended in 1967. This time Finley had laid the groundwork for his escape by quietly gathering the votes of his fellow American League owners. On October 18 the league formally approved his move to Oakland as part of a package deal that included the league expanding to two cities, including Kansas City. Finley likely chose Oakland over other possibilities because it had a brand new ballpark ready to go. The city of Oakland, cognizant of whom they were dealing with, drew up a strict 20-year lease with no option for moving. Finley signed, but was talking with Toronto by 1970.

Once he was settled in Oakland, Finley branched out to buy two other sports teams: the Oakland Seals of the National Hockey League (renamed the California Seals), and the Memphis Stars of the American Basketball Association (renamed the Tams). Both teams changed colors to Finley’s favored green and gold, but neither could draw fans or win games. In 1974 both teams were taken over by their respective leagues.

Meanwhile, with his baseball club gradually improving, Finley worked equally hard to keep them from getting his money. He went through very public and openly hostile holdouts with Reggie Jackson (in 1970) and Vida Blue (1972), both times using humiliation and degradation to get his stars to come to terms. Both men were popular and well-liked players who never again seemed to play with the carefree joy they had before Charlie put them in their place. In both cases, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, rarely considered friendly to the interests of players, intervened to get things settled.

A funny thing about Finley was that he could be very generous on his own terms. He was reprimanded or fined several times for giving impromptu performance bonuses (which were and continue to be forbidden) to players for pitching a no-hitter, hitting a game-winning home run, or some other such thing. For many years he offered to invest the money of players in the stock market risk-free — Finley gave the player all gains and assumed all losses. At contract time, on the other hand, he considered it a personal insult if a player was not satisfied with his offer. As he told writer Bill Libby, “We have not won a pennant, but we will win one, we will win more than one with these players who are like my own sons, and I am only sad when they will not accept my counsel, the counsel of a man who is older and wiser than they.”12

Led by Blue, the A’s won 101 games in 1971 and the division by 16 games. The team fell short in the playoffs, but the core of this team remained nearly intact for five straight division titles. Bando, Campaneris, Dick Green, Jackson, and Rudi held down five of the eight regular lineup spots. Hunter, Blue, and Fingers starred on the pitcher’s mound.

Finley made two great trades that solidified the dynasty. After the 1971 season he traded Rick Monday to the Cubs for left-handed pitcher Ken Holtzman. A year later, now realizing that he needed a center fielder, Finley traded Bob Locker to the Cubs for Billy North. North anchored center field for the A’s for the next several seasons.

With his great young team in place, Finley constantly tinkered with the depth of his club, making trade after trade, either to fill in the gaps or because he liked making deals. Finley acquired a huge number of veterans to play a role during the five-year string of division titles. He outworked the other general managers during most of his 20-year career as owner, but he pushed himself even harder once he realized how good his team had become. In 1972 alone he made 19 trades, many of them during the season. Dick Williams later claimed that he found out about trades by seeing who was in the dugout when he showed up for work.

For spring training of 1972, Reggie Jackson showed up with a mustache. After privately trying to get Jackson to shave it off, Finley instead decided to capitalize on the act of rebellion. He staged a “Mustache Night,” let mustached patrons in for a reduced price, and gave each player a small bonus if they wore mustaches for that night’s game. All players and coaches obliged, and most kept their mustaches all season. A few even sported beards. The team, dubbed “The Mustache Gang” in the press, went on to beat the clean-cut Cincinnati Reds in the World Series.

The Sporting News named Finley its “Man of the Year.” Jackson and Blue, each once the biggest star in all of baseball, were now back in their rightful place as mere players. The only star on the team was Finley. In case anyone had missed it, he reprinted the Sporting News cover photo in the 1973 A’s yearbook.

After another pennant the next season, the 1973 World Series finally turned Finley into a national pariah, an identity he would never overcome. After Mike Andrews made two errors in the 12th inning of Game Two, helping the Mets beat the A’s 10-7, Finley forced Andrews to sign a statement claiming that his shoulder was injured and that he could no longer play. Finley added Manny Trillo to the roster to replace Andrews, who left the team and flew home. The players, in the middle of a deadlocked series, rallied to their teammate. Sal Bando: “That’s a joke. I’ve seen some bush things on this club, but this is going too far.”13 Reggie Jackson added, “All that nonbaseball stuff takes the little boy out of you.”14 The whole team seemed defeated and uninterested in playing. The A’s players showed up for Game Three in New York with Andrews’ number on their sleeves.

Commissioner Kuhn ordered Finley to reinstate Andrews, who reached New York in time for the fourth game the next night and pinch-hit in the eighth inning. He received a prolonged standing ovation from the New York crowd — Finley did not stand — before grounding out off Jon Matlack. One A’s employee expressed the general feeling: “Although it hurt Andrews, a lot of people were glad it happened because for the first time it directed attention at the way Finley treated people, even if it was far from the first time he’d treated them that way. All of a sudden he was not just a quaint old guy, a fellow who did funny things, but a man who could hurt people and did.”15 The A’s released Andrews at the end of the season, and he never again played in the major leagues.

The aftermath of the seventh-game victory was eerie. The Oakland locker room was subdued, as if everyone just wanted to get out and go home. Yogi Berra, the manager of the Mets, walked in and commented, “This doesn’t look like a winning dressing room to me.” Manager Dick Williams announced that he was quitting, and Jackson said, “I wish I could get out with him.” When a writer suggested to Jackson that Finley deserved credit for getting the team riled up, the star responded, “Please don’t give that man credit. … It would have been the easiest thing in the world for this team to lie down because of what that man did. He spoiled what should have been a beautiful thing.”16

At this point in the story, Reggie Jackson’s star finally rose and replaced Finley’s at the top of his team. He was voted the World Series MVP, not only for his play on the field, but for the way he conducted himself as a sincere, intelligent man in the face of what was finally recognized as nearly intolerable working conditions. Finley had spent years trying to be the center of the team, and he had succeeded even after his team had so many star players. Finley’s childish behavior in 1973 challenged his players to step forward, and Jackson did.

The departure of Williams resulted in yet another long circus, as Finley first publicly supported Williams’s decision but later refused to let him out of his contract. No one quit on Finley. Williams signed to manage the Yankees, a move the American League blocked. Finley demanded compensation, which the Yankees refused to give, precluding Williams from getting the job. Williams remained out of work until midsummer, when he signed to manage the lowly California Angels. The A’s lingered without a manager until late February, when Finley finally hired old friend Alvin Dark for 1974.

By 1974 much of the fun was gone. While Finley had flown in to get retractions from players for the occasional criticism in years past, by now the pretense of kissing up to the boss was ancient history. Captain Sal Bando claimed, “I would say all but a few of our players hate him. It binds us together.”17

The 1974 team struggled to hold off the surprising Texas Rangers and won only 90 games. Once the postseason bell rang, they rallied to capture their third straight world championship. Unbelievably, yet another player-relations nightmare dominated the 1974 postseason. This time it involved not a backup infielder but the contract of a 25-game winner, Jim “Catfish” Hunter.

In January 1974 Hunter had signed a two-year contract for a salary of $100,000 per year. The arrangement included a wrinkle: Half his salary was to be paid into a life-insurance fund as a form of deferred payment. On the day before the World Series began in Los Angeles, the story broke that Finley had not paid the mandated $50,000 to the insurance company, even after receiving written notice in mid-September. Hunter reportedly planned to ask for his release from his contract as soon as the World Series was over. Finley, obviously more worried than he admitted, went into the clubhouse with American League President Lee MacPhail to present Hunter with a check for the amount due. Hunter refused to accept the check and told Finley that they would discuss it after the Series was over.

After a month of rumors in the press, a hearing was held on November 26 in New York City in front of arbitrator Peter Seitz. On December 13 Seitz found for Hunter and declared him a free agent. The baseball world went berserk — never before had a player of Hunter’s caliber been available to the highest bidder at the height of his career. A three-week bidding war ensued among nearly every team in baseball. The Yankees landed Hunter with a five-year deal totaling $3.75 million, more than three times the annual rate for the top stars in the game. The players could not help but notice what they could make on the free market.

After one last division title, but no World Series, the Athletic dynasty effectively died on December 12, 1975, when arbitrator Seitz dropped another bombshell. This time he declared Dodgers pitcher Andy Messersmith and Expos pitcher Dave McNally free agents after they had played out the season without signing contracts. This decision ultimately put an end to the effects of baseball’s reserve clause, which bound a player to his team in perpetuity.

Finley’s team was finished. Once Charlie had to bargain with players as equals, once he had to look an agent in the eye and come to terms, well, he just was not capable of competing. Charlie Finley did not, and could not, operate in this manner. The whole team hated him and had seen their teammate Hunter go on to happiness and wealth in another city, leaving little doubt what they were going to do with their freedom. Finley traded Jackson and Ken Holtzman during spring training in 1976. Sal Bando, Gene Tenace, Bert Campaneris, Rollie Fingers, and Joe Rudi (along with Jackson, now an Oriole) became free agents that fall. By 1977 the Athletics were in last place, behind even the first-year Seattle Mariners.

In June 1976 Finley attempted to make the best of a bad situation by selling Blue to the Yankees and Fingers and Rudi to the Red Sox for a total of $3.5 million. Because he was about to lose all three at the end of the year anyway, it seemed like a wise idea. Bowie Kuhn voided the sales, claiming they were not “in the best interests of baseball.” Finley sued Kuhn for restraint of trade, but lost his case a few years later. Even with the passage of time, it is hard to find justification for Kuhn’s action, other than trying to destroy Finley.

After three losing seasons, in 1980 Charlie hired Billy Martin to run the team, and there were signs that the team was going to rise again, behind new stars like Rickey Henderson and Mike Norris. But Finley’s time was over. Shirley Finley filed for divorce that summer, and when she refused to accept a share of the baseball team, he was forced to sell. He eventually sold to Walter A. Haas Jr., before the next season.

Finley lived out his remaining days in Chicago running his insurance company. He died in 1996, leaving seven children. For a man who spent 20 years in the game and won three championships, he left very few friends in the game.

A version of this biography appeared in “Mustaches and Mayhem: Charlie O’s Three Time Champions, The Oakland Athletics, 1972-74” (SABR, 2015), edited by Chip Greene.

Notes

1 Mark L. Armour and Daniel R. Levitt, Paths to Glory (Dulles, Virginia: Brassey’s Inc., 2003), 234.

2 Herbert Michelson, Charlie O (New York: Bobbs Merrill, 1975), 294.

3 Michelson, Charlie O, 94.

4 Bill Wise, ed., The 1963 Official Baseball Almanac (Greenwich, Connecticut: Fawcett, 1963), 58.

5 “Finley’s Follies,” Sport Annual, 1966.

6 Edwin Shrake, “A Man and a Mule in Missouri,” Sports Illustrated, July 27, 1965, 43.

7 Bill Libby, Charlie O. & The Angry A’s (Garden City New York: Doubleday, 1975), 275.

8 John Peterson, The Kansas City Athletics (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 210.

9 Bill James, The 1986 Baseball Abstract,(New York: Ballantine Books, 1985).

10 John Peterson, The Kansas City Athletics (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 210.

11 Brent Musberger, “The Charlie O. Finley Follies, Sports Illustrated, September 4, 1967.

12 Libby, Charlie O. & The Angry A’s, 10.

13 Michelson, Charlie O, 251.

14 Michelson, Charlie O, 251.

15 Libby, Charlie O. & The Angry A’s, 20.

16 Libby, Charlie O. & The Angry A’s, 279-280.

17 Armour and Levitt, Paths to Glory, 256.

Full Name

Charles Oscar Finley

Born

February 22, 1918 at Ensley, AL (US)

Died

February 19, 1996 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.