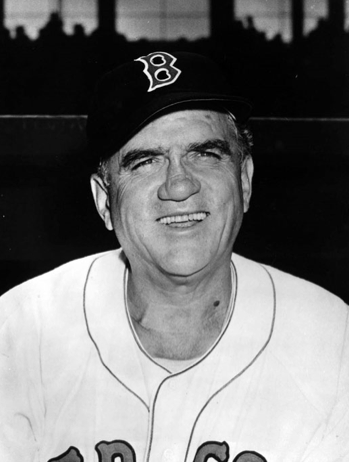

Steve O’Neill

With a flattened nose and the grim jaw of a heavyweight boxer, Steve O’Neill looked like someone born to be a catcher, and for much of his 17-year major-league career he was arguably the best all-around backstop in the game. An extremely smart man, O’Neill did all the things a good catcher is supposed to do, and he did them better than almost anyone else. His legendary throwing arm stymied would-be basestealers, his agility behind the plate made him one of the game’s best at blocking pitches in the dirt, and he was universally regarded as a great pitch-caller. “He was one of the few who had the guts to call for a curveball with the tying or winning run on third base,” teammate George Uhle said. “ ‘Don’t worry ’bout throwing it in the dirt,’ he’d say. ‘I won’t let it get by me.’ And he wouldn’t.”1 After spending several years in the majors as the prototypical great-defense, no-offense catcher, by the end of the Deadball Era O’Neill had also matured into a fine hitter, batting better than .300 every year from 1920 to 1922.

With a flattened nose and the grim jaw of a heavyweight boxer, Steve O’Neill looked like someone born to be a catcher, and for much of his 17-year major-league career he was arguably the best all-around backstop in the game. An extremely smart man, O’Neill did all the things a good catcher is supposed to do, and he did them better than almost anyone else. His legendary throwing arm stymied would-be basestealers, his agility behind the plate made him one of the game’s best at blocking pitches in the dirt, and he was universally regarded as a great pitch-caller. “He was one of the few who had the guts to call for a curveball with the tying or winning run on third base,” teammate George Uhle said. “ ‘Don’t worry ’bout throwing it in the dirt,’ he’d say. ‘I won’t let it get by me.’ And he wouldn’t.”1 After spending several years in the majors as the prototypical great-defense, no-offense catcher, by the end of the Deadball Era O’Neill had also matured into a fine hitter, batting better than .300 every year from 1920 to 1922.

Stephen Francis O’Neill was born on July 6, 1891, the 10th of 13 children of Mike and Mary O’Neill, and the fifth of the clan born in America. The first five were born in Ireland; the rest, including Steve, in the coal-mining town of Minooka, Pennsylvania, three miles southwest of downtown Scranton. Like most children who grew up in mining towns around the turn of the century, Steve started working in the mines after his tenth birthday, separating slate and other refuse from the anthracite coal, receiving a few pennies a day for his troubles. By the time he reached the employment stage, the average Minooka youngster had loftier ideas than a lifetime of toiling in the bowels of the Earth a couple of hundred or more feet below the surface. His inspiration came from watching his older brothers Mike and Jack have success in St. Louis as major leaguers. It demonstrated that there were less dangerous ways to make a living.

As a youngster, Steve could box and wrestle, and he admired athletes of any description, but baseball was the only sport he ever really cared about. As a boy he played it from snow season to snow season. Besides Mike and Jack, another brother, Jim, carved out small major-league careers. In fact, Mike and Jack, both older than Steve, became the first brother battery in major-league history. Mike pitched for the St. Louis Cardinals for four years, posting a 32–44 record with a 2.73 ERA. Jack was a catcher for five years with the Cardinals, the Chicago Cubs, and the Boston Beaneaters (later the Braves). Steve’s younger brother Jim played two years with the Washington Senators as a shortstop before injuries cut his career short. The oldest brother, Pat, might have made it five O’Neills in the majors, but he hurt his hand in a mining accident.

Thus, save for the Delahantys, the O’Neills are the only other family with at least four brothers who played in the major leagues.

Steve’s brother Pat saw in the youngsters of Minooka the golden opportunity denied him. So with youngest brothers Steve and Jimmy as the nucleus, Pat started what might have been America’s first baseball school. Each day from early spring until late into the fall, he tutored and fathered his unique collection of protégés. He had enough for a team over time and a few reserves. Despite their tender ages, the semipro Minooka Blues (managed by Pat), soon ruled the region. In the words of one writer in the early 1900s, “they look like boys but play like men.” A scout had only to observe the Blues’ penchant for baseball and their flair for teamwork before his fountain pen and pro contracts appeared. Thus were born the famous Minooka Blues and four major leaguers from this small town, Steve and Jim O’Neill along with Mike McNally (Boston AL, New York AL and Washington) and Charley Shorten (Boston AL, Detroit, St. Louis AL and Cincinnati). The Blues played each week, usually for a $500 side bet and the gate receipts. [The Sporting News, February 7, 1962] After years of playing for the Blues, Steve O’Neill received his first professional contract in 1910, when the Class B Elmira Colonels, then managed by his older brother Mike, offered him a contract. Actually, Mike did not think much of his little brother as a baseball player, but he needed a second-string catcher and figured Steve would fit the bill. Bill James has written that Mike was also trying to keep Steve out of the mines.

Steve got little playing time until an injury to the starting catcher opened the door. He batted only .200 in 28 games, but handled himself behind the plate as though he had been born there, and attracted the attention of a friend of Connie Mack’s, who talked so much about the youngster that Philadelphia Athletics co-owner/manager Mack signed him. Steve reported to the Athletics at spring training in 1911 with a beat-up catcher’s mitt and spiked shoes with holes in them. The first thing Mack did was send him to a sporting-goods store to get new equipment. Mack said, “If you want to play big-league baseball you must have big-league tools.”

Before the start of the 1911 season, Mack sent O’Neill to Worcester (Massachusetts) of the New England League, where he played for Jesse Burkett, who owned and managed the Busters. O’Neill caught all but a few games, again handled himself like a pro, and won the confidence of the entire pitching staff. When Mack’s longtime captain and first baseman, Harry Davis, signed to manage the Cleveland club for the 1912 season, Mack agreed to let the Naps have O’Neill for $3,000. Davis knew Mack had Wally Schang available in the minors and O’Neill was expendable. O’Neill played nine games for the Indians late in the 1911 season.

Cleveland is where Steve made his home for the next 12 years, though he didn’t become the team’s full-time catcher until 1915. For nine consecutive seasons, he was the most durable catcher in the game and in 1920, the year Cleveland celebrated a winner, O’Neill caught 149 out of the 154 games played by his team. His defense was so outstanding that it offset several years of anemic hitting. In 1917, for instance, the right-handed O’Neill batted only .184, yet caught 127 games. Despite his struggles at the plate, nobody ever thought to relieve him of his job. “When you have a catcher like Steve O’Neill,” Indians manager Lee Fohl said, “you don’t care whether he hits or not.” But that all changed with the appointment of Tris Speaker as his manager. Speaker agreed that O’Neill was one of the best catchers in the business, but saw no reason why he shouldn’t be a good hitter as well. “Nobody with your guts and determination should be such an easy mark at the plate,” Speaker told O’Neill. “Instead of floundering around .240, you should be a .300 hitter every year.” “That would suit me fine,” Steve said, “only how do I do it?” “Well,” said Speaker, “in the first place go up there figuring you’ll get a hit, not that you won’t. In the second, try to outthink the pitcher. And in the third, stop swinging at bad pitches.”

The advice paid off, as O’Neill’s walk totals began to climb while his strikeout rate declined. In 1919 he batted .289 in 125 games, knocked in 47 runs and pasted 35 doubles, fourth best in the league. From 1920 to 1922 he batted over .310 every year, and ranked in the top ten in on-base percentage each season. During the Indians’ championship 1920 campaign, O’Neill was behind the plate for 100 straight games, and played every inning of 148 of the Indians’ 154 games, yet still finished the year with a .321 average and a .408 on-base percentage. O’Neill might have played in more games, but for Speaker giving him five days off to tend to his ailing wife, Mary, who gave birth to twins in midseason. (O’Neill and Mary had four children in all.) O’Neill’s crowning achievement may have been his play in the 1920 World Series against the Brooklyn Robins. He won the first game single-handedly with a pair of run-scoring doubles off Rube Marquard, whom the Indians feared more than the remainder of the Brooklyn pitching staff. By the end of the Series, one the Indians won with ease five games to two, O’Neill was the toast of the baseball universe. Even the conservative baseball writers went overboard in describing how well he had played in the Series. But not even the most prolific of the writers could begin to pay the “king of maskmen,” as the 29-year-old catcher was termed, a compliment bestowed upon him by the colorful character who managed the Robins, Wilbert Robinson.

The 1920 Championship season saw both highs and lows – winning the World Series and the death of his good friend Ray Chapman. In the August 16 game against the Yankees, a Carl Mays fastball hit Chapman in the head and he passed away later that evening. In the game O’Neill hit a homer in the second and drove in the winning run with a two-out single that scored Tris Speaker in the 4-3 win. When the Indians arrived back in Cleveland and viewed Chapman’s body at the Daly’s house before the funeral, the newspaper reported that both O’Neill and Jack Graney fainted while seeing their friend in the casket.

Robby’s tribute came in a man-to-man fashion, after O’Neill blocked off big Ed Konetchy so well at the plate when the Robins desperately needed a tying run. A great catcher himself (for the talented Baltimore Orioles), Robinson came rushing out of the dugout protesting vehemently and, in the words of one observer: “It was difficult to tell whether he was going to throw a fit or start a riot.”

The only thing Robinson’s tirade did was to stir up the partisan Brooklyn crowd, which screamed for O’Neill’s scalp. The noise and clamor was loudest as Robinson, on his way back to the bench, brushed O’Neill, and out of the side of his mouth, chirped: “Nice block, me lad, I’d be proud of it myself.”

O’Neill had a strong arm and even the great Ty Cobb didn’t often take liberties against him, although the last of Cobb’s record 96 thefts in 1915 was with Steve catching. O’Neill thought his throw to second had beaten Cobb and was still steaming when Cobb came up for his next at-bat.

“What do you think this is, the World Series?” Cobb snapped. “I’m out to stop you every chance I get. World Series or not,” O’Neill growled. Steve treated Ty with complete disrespect and probably is the only catcher ever to grind his knees into the middle of Cobb’s back while blocking off home plate and get away with it. Neither Cobb nor his spikes could awe the former boy miner.

As the games behind the plate mounted and O’Neill’s 5-foot-10, 165-pound frame endured more punishment, his offensive production began to slacken. In 1923 his average plummeted to .248 (although his on-base percentage was a robust .374), and after the season the Indians traded him to the Boston Red Sox along with pitcher Dan Boone, outfielder Joe Connolly, and infielder Bill Wambsganss for first baseman George Burns, catcher Roxy Walters, and infielder Chick Fewster. In 1924 O’Neill appeared in 100 games for the last time in his career, batting just .238 with 16 extra-base hits, but still getting on base proficiently with a .371 on-base percentage. He was picked up off waivers at the end of the ’24 season by the New York Yankees and played in only 35 games during the 1925 season before he was released. He hooked on with Reading of the International League and played in 34 games (29 behind the plate), hitting .266. After spending the 1926 season with Toronto of the International League, where he hit .264 in 135 games, O’Neill returned to the majors with the St. Louis Browns in 1927. During his last season with the Browns, 1928, O’Neill was almost killed when a truck hit a New York City cab he was riding in. The police and medics who rushed to the scene took one look at Steve (without realizing his identity) and summoned a priest to give him the last rites of the Catholic Church. O’Neill not only lived through the night but, despite critical injuries, rallied so magnificently that he amazed the specialists attending him. He managed just 7 hits in 24 at-bats in his final season. He ended his career with a respectable .263 average, 1,259 hits, and 537 RBIs.

After retiring as full-time player in 1928, O’Neill stayed in baseball as a manager for the next 26 years. He became one of the most consistent field generals in baseball history. In 1929, O’Neill was named player-manager of the Toronto Maple Leafs and led them to a second-place finish with a record of 92-76. He also managed Toronto in 1930 and 1931, finishing fourth and fifth. (O’Neill continued to hit and pinch-hit until 1934, all in the minors, and played one game for Beaumont in 1942, going 1-for-3, when he was 51 years old.)

O’Neill continued to write his own name on the lineup card, catching 58 games in 1930 and 76 games in 1931 at the age of 39. The additional work caught up with his offense, however, as his batting average dropped from .308 in 1930 to .226 in 1931. O’Neill moved to the Toledo Mud Hens for the next three years – in 1932 as a player-coach and as a player-manager for the 1933 and ’34 seasons. His professional playing career was by this point definitely waning; he caught only 41, 18, and 19 games respectively in those years with Toledo.

In 1934, his last year as a player, O’Neill hit .313 (21-for-67) with five doubles. Toledo was an affiliate of the Cleveland Indians. O’Neill had a knack for getting the most out of his pitchers at every stop of his career. So when Walter Johnson needed a pitching coach for the 1935 Indians, he added O’Neill to his staff. His pet project was to get Monte Pearson to continue his resurgence after a nice year in Cleveland. Pearson, who played in Toledo in 1932 and parts of 1933, credited O’Neill with helping him to regain his confidence. After a disappointing season in 1932, Pearson came back, thanks to O’Neill, to post an 11-5 record with a 3.41 ERA for the Mud Hens and a 10-5 record with a 2.33 ERA for the Indians. He went on to win 18 games with the Indians in 1934. The O’Neill magic had its limits, though, as Pearson fizzled in 1935.

Halfway through the 1935 season, Johnson was fired after the Indians got off to a bad start, and O’Neill was named the manager; he led the Indians to a 36-23-1 record over the last 60 games to finish third. He managed Cleveland for the next two years, guiding them to back-to-back winning seasons, though the club never finished higher than fourth, before giving way to Ossie Vitt in 1938.

O’Neill wound up back in the International League, leading the Buffalo Bisons to two playoff appearances in his three years there. The Detroit Tigers came calling and hired Steve to be a coach for the 1941 team. In 1942 he was hired to lead the Tigers’ Double-A team in Beaumont of the Texas League. The Exporters almost gave O’Neill his first title as they finished first with a record of 89-58. Shreveport beat Beaumont in the playoffs. In 1943, O’Neill replaced Del Baker as manager in Detroit and began a six-year reign as the Tigers’ skipper. After finishing fifth in 1943 and second in ’44, his Tigers won the 1945 American League pennant behind the brilliant pitching of Hal Newhouser, and then defeated the Chicago Cubs in the World Series.

The Tigers finished second in 1946 and 1947 and fifth in 1948. Red Rolfe replaced O’Neill in 1949 and he returned to Cleveland as a coach. After the 1949 season, the Red Sox hired him as a scout, but then, as the 1950 season started, he replaced Kiki Cuyler as the third-base coach. In June Joe McCarthy resigned as Red Sox manager because of fatigue, and on June 23 general manager Joe Cronin named O’Neill as McCarthy’s replacement.

Taking over a club that had lost 11 of 13, O’Neill managed the final 95 games with an impressive record of 63-32 and led the Red Sox to a third-place finish. He led the club to an 87-67 record in 1951, but was not brought back for the 1952 season. He remained a scout for the Red Sox until late June, when he was named to replace Eddie Sawyer as manager of the struggling Philadelphia Phillies. Again he made an immediate impression, taking over a sixth-place team seven games below .500 and finishing 59-32 over the final 91 games while getting Philadelphia to a fourth-place finish. O’Neill managed the next year and half with a winning record before being fired in the middle of ’54 season.

Over 14 seasons with four different franchises, O’Neill’s clubs posted a 1,040–821 record, good for a .559 winning percentage. He never had a losing season; only Joe McCarthy did that over a longer career. O’Neill wasn’t the fiery, aggressive type you might want to see as a pilot; he combined a stout heart with a sympathetic understanding of youngsters. He enjoyed both the respect and the friendship of his players. He was a player’s manager all the way. His greatest assets as a manger were the devotion he inspired among his players and the way he could handle a pitching staff.

After leaving the Phillies, O’Neill worked as a scout and also as administrative assistant to Indians general manager Hank Greenberg. He later worked for the Cleveland Recreation Department, mostly running baseball clinics for youngsters. He was still working in that position when he died of a heart attack on January 26, 1962. At O’Neill’s death, his former ace pitcher Hal Newhouser said: “He was the greatest I have ever played for. He was unsurpassed in his ability to handle young players.”2 Visiting O’Neill during the winter of 1943-44, Newhouser asked to be traded because he wasn’t being pitched in the rotation. O’Neill agreed to pitch Newhouser every fourth day. He did, and Hal won 29 games in 1944 as Detroit missed the pennant by a whisker. He won 25 in the 1945 championship campaign. “If it hadn’t been for O’Neill, I would have been just an average pitcher,” Newhouser said.

“Baseball has lost a good friend,” Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick said. “He was a man who never made an enemy and had a long and distinguished career as a player, coach and manager.”

He and his wife, Mary, had four daughters; Madlyn, Johann, and twins Rose and Olive. The latter two married professional baseball players Henry Nowak and James “Skeeter” Webb.

Sources

Mike Sowell, The Pitch That Killed; The Story of Carl Mays, Ray Chapman, and the Pennant Race of 1920 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1989).

Al Hirshberg, Baseball’s Best Catchers (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1966).

Russell Schneider, The Cleveland Indians Encyclopedia (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2001).

Chic Feldman, “The Life of Steve O’Neill.” The Sporting News Baseball Register 1946.

Baseball Digest

Baseball Magazine

Boston Post

Chicago Daily News

Cleveland News

Cleveland Plain Dealer

Detroit News

New York Times

Oneonta Star

Scranton Tribune

The Scrantonian

The Sporting News

Notes

1 Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 27, 1962.

2 Chicago Tribune, January 29, 1962.

Full Name

Stephen Francis O'Neill

Born

July 6, 1891 at Minooka, PA (USA)

Died

January 26, 1962 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.