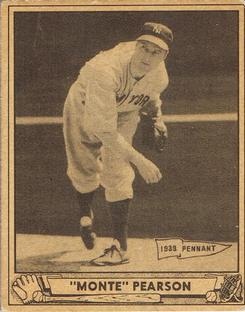

Monte Pearson

In their long and storied history, the New York Yankees have sent many fine pitchers to the mound in the World Series. Hall-of-Famers like Lefty Gomez, Whitey Ford, and Mariano Rivera have left their mark on the record books with their autumnal performances in pinstripes. Arguably, though, the Yankees’ top all-time Fall Classic hurler is not one of these baseball legends, but rather a talented yet injury-prone right-hander from Fresno, California, named Monte Pearson.

In their long and storied history, the New York Yankees have sent many fine pitchers to the mound in the World Series. Hall-of-Famers like Lefty Gomez, Whitey Ford, and Mariano Rivera have left their mark on the record books with their autumnal performances in pinstripes. Arguably, though, the Yankees’ top all-time Fall Classic hurler is not one of these baseball legends, but rather a talented yet injury-prone right-hander from Fresno, California, named Monte Pearson.

A member of the starting rotation for the great Yankee clubs of the late 1930s, Pearson won his only start in each of four consecutive Series, culminating in a near no-hitter versus Cincinnati in 1939. He remains one of the top World Series pitchers of all time in winning percentage (1.000), WHIP (0.729), and ERA (1.01) (20 innings minimum). He also pitched the first-ever no-hitter at Yankee Stadium in 1938. Despite these accomplishments, Pearson had a reputation as an underachiever that he was never able to wholly overcome. A popular figure in Fresno following his years in baseball, he embarked on a second career as a public health official; however, in a highly publicized case, he was convicted on charges of extorting bribes, resulting in a fall from grace for the former World Series hero.

Marcellus Montgomery Pearson was born September 2, 1908, in Oakland, California, the youngest of the five children of Arthur and Lula (Tidwell) Pearson.1 His father, a mining engineer, died in a mining accident in 1910.2 After his mother remarried, the family moved to the Fresno area.3 In high school, Pearson caught and played third base before he was eventually moved to the mound. He pitched briefly for Bakersfield of the California State League in 1929 before the league “went on the rocks” and he joined the semi-pro Fresno Acorns.4 A local scout saw him pitch and recommended him to the PCL’s Oakland Oaks, who signed him.5

The six-foot-tall, 175-pound right-hander started the 1930 season with the Oaks. Used primarily as a reliever by manager Carl Zamloch, Pearson was sent down in early August to Phoenix of the Class D Arizona State League. There he started and went 2-0 in five games to help his new club qualify for the league playoffs. At season’s end, he wedded Cleota “Cleo” Wimer, whom he had met through her brother, also a ballplayer.6

In 1931, Pearson pitched well; by mid-June, the Oakland papers were speculating about which major league team would sign him. He finished with a 17-16 record and was purchased by the Cleveland Indians for $35,000.7 At Cleveland’s 1932 spring camp, Pearson impressed skipper Roger Peckinpaugh with his “dazzling fastball.”8 He made his major league debut on April 22 in mop-up duty against Detroit. Behind 10-2, Pearson kept Detroit off the scoreboard in his first inning of work, but next inning gave up six runs before Peckinpaugh took pity on him and called for a reliever. He was eventually sent down to Toledo after compiling an unsightly 10.13 ERA. With the Mudhens, Pearson pitched regularly; though he went 3-9, his ERA was a respectable 3.99.

Pearson returned to Toledo to open the 1933 campaign. He blamed his 1932 troubles on wildness caused by being overweight. “…I was close to 15 pounds heavier than I was when winning games in Oakland. Went on a diet and with the steady work and coaching I received from [Mudhens manager] Steve O’Neill, I acquired control.”9 The leaner Pearson dominated the American Association, winning 11 of 16 decisions including a two-hitter with 15 strikeouts (seven of them consecutive) against Columbus in the first night game played in Toledo.10 Shortly thereafter, Pearson was recalled by Cleveland in one of their first moves under new manager Walter Johnson.11

In Pearson’s first major league start, he pitched well, losing a 3-2 decision to Washington due to three unearned runs. His first win came a couple of starts later against Boston by a 2-1 score. As the season progressed, he continued to pitch effectively: though he sometimes struggled with his control—he walked 11 in a game against the Yankees—he kept the ball in the park and allowed relatively few hits. His best performance came on August 29 at home against Washington. Before a crowd of 63,000, Pearson held the powerful Senators’ offense without a hit through eight innings before Ossie Bluege singled leading off the ninth. He ultimately had to settle for a complete game two-hitter against the eventual league champions.

Pearson finished with a 10-5 record and a league-leading 2.33 ERA. While this ERA may not impress the modern reader, it was a noteworthy achievement in context given the small ballparks and lively ball of the 1930s. Had he pitched 16 more innings, baseball-reference.com would rate his ERA+ of 194 as the second-best mark of the entire decade, trailing only Lefty Grove’s 217 ERA+ in his legendary 1931 campaign.12 Pearson’s selection as one of three pitchers on the Sporting News “all-star freshman team” was a no-brainer.13 He credited Johnson at least partially for his success. “He put this sort of a spirit in me—when you go out to the mound, say to yourself you are just as good as the fellow facing you and that you can get him out of there.”14 For his part, Johnson said he had never seen a pitcher with as much natural talent and that Pearson should be a 30-game winner.15

Both the Indians and Pearson got off to strong starts in 1934. By late May, he had a 6-2 record, while the Indians were atop the standings. But he began to get hit harder in June, and the Indians proved unable to keep pace with Detroit and the Yankees. Pearson ended the season with an ERA of 4.52 to go with 18 wins.

Cleveland had high hopes for the 1935 campaign. The Sporting News noted, “Everyone connected with the club here is firmly convinced that 1935 is to be Cleveland’s year.”16 But the organization’s optimism proved to be misplaced as the club finished a distant third. A contributing factor was Pearson’s poor performance; he struggled with his control and gave up runs in bunches, finishing with a disappointing 8-13 record and 4.90 ERA.

Now two seasons removed from his dazzling debut, Pearson was something of an enigma. “Pearson has such a rich store of natural talent that spring experts annually have predicted he will be one of the game’s big sensations,” stated The Sporting News. However, “[M]any followers of the Indians are agreed that Pearson lacks a generous helping of competitive spirit, that he is so constituted that it makes little difference to him whether he wins 15 games or 20 …”17 In December 1935, the Indians sent Pearson and pitcher Steve Sundra to the Yankees for pitcher Johnny Allen. Famed sportswriter Fred Lieb noted that “[w]hen the deal first was made, no one in New York exactly shouted his joy from the house-tops. New Yorkers knew Allen had a turbulent nature … but they liked the scrappy hurler.”18 Yankee owner Colonel Jacob Ruppert admitted that “we made this deal to get Sundra. We felt Allen was a better pitcher than Pearson, but we disguised our hand. The man we really wanted was Sundra . . . “19

Nevertheless, Pearson was happy about the trade and made no bones about why. “[W]e are in the game for the revenues, and as the Yanks are always up there toward the top year in and year out, it will mean more for me.”20 Pearson’s focus on income may have been related to his growing family, as his first child, Wesley, was born during spring training in 1936.

Pearson quickly showed his new bosses that they had underestimated him. He won eight of his first nine decisions and helped New York move into first place in May, a spot they would never relinquish. He was named to the All-Star team (though he didn’t appear) and continued to pitch well, finishing with a 19-7 mark and an ERA of 3.71, lowest among Yankee starters. He also had a good year at the plate, hitting .253 with 20 runs batted in. It all added up to 4.9 Wins Above Replacement, behind Lou Gehrig and Bill Dickey (but ahead of rookie center fielder Joe DiMaggio) for third on the club.

Unfortunately, in the eighth inning of his final start of the season, Pearson suffered a muscle strain, putting his availability for World Series duty in doubt.21 This elicited chatter from the press corps that Pearson’s ailment wasn’t serious and that he lacked toughness. “There is no escaping the fact that Pearson’s condition is in a good measure mental,” wrote one columnist. “Monte is the quiet, serious type who does a lot thinking about himself and quite often he conjures up things that don’t exist.”22

Initial reports indicated that Pearson wouldn’t take the mound in the Series. 23 But in a pattern that would repeat itself in future Fall Classics, Pearson healed quickly and started Game 4 against the Giants’ ace, Carl Hubbell. “King Carl” was in the midst of one of the most dominant stretches of any pitcher in baseball history; he had won his last 16 regular season decisions and had also beaten the Yankees in Game One.24

A World Series record crowd of 66,669 filled Yankee Stadium to watch the Giants try to even the Series at two games apiece.25 One of the attendees was a 14-year-old Giants fan named Arnold Hano. “Pearson walked with a confident manner—he looked like a man who knew how to go about his business,” said Hano. “What surprised me was how softly he threw. He was a curveball pitcher. He had the Giants off-balance all day.”26

The Yankees struck early for four runs, the last two on a homer by Gehrig that landed near Hano in the bleachers.27 The Giants touched Pearson for single runs in the 4th and 8th innings but managed only seven singles in the contest and fell rather meekly to the Yankees, 5-2. Pearson went the distance and had two hits against the Giants’ ace. “After Pearson had beaten the great Hubbell, Yankee manager Joe] McCarthy announced that he was looking for a blind man suffering from hardening of the arteries and fallen arches so he could send him out there today,” read one tongue-in-cheek recap. 28 Giants’ fans like Hano were less amused. “That was a terrible day,” he recalled more than 84 years later.29

In 1937, Pearson briefly held out before reporting to spring camp. Early on he rolled his ankle, the first of several injuries he suffered that year.30 He still got off to his typical strong start, winning his first four decisions, including a one-hit shutout against the White Sox. But in May, he was diagnosed with a torn muscle31 and was sidelined for a full month. He returned in June, but his arm problems continued, and he pitched only intermittently. Nevertheless, at season’s end he boasted a 9-3 record with an ERA of 3.17 as the Yankees prepared to face the New York Giants in the World Series for the second consecutive year.

Despite Pearson’s injury-riddled campaign, beat writer Jack Smith picked him as one Yankee likely to emerge as a surprise Series hero.32 Outfielder George Selkirk agreed. “He’s really a GREAT pitcher and may surprise everybody.”33 The powerful Yankees won Games 1 and 2 at Yankee Stadium by identical 8-1 scores behind Gomez and Red Ruffing. Pearson started Game 3 and if anything, outpitched his more celebrated rotation-mates. By the time the Giants had their first baserunner on a Lou Chiozza bunt single in the fifth, the Yankees led, 5-0. Though the Giants managed a run in the seventh, Pearson cruised until the ninth, when they loaded the bases with two outs before Johnny Murphy relieved and got the final out for the save. Pearson’s final pitching line: 8 2/3 innings, five hits, two walks, and a run. After a Game 4 loss, the Yanks took Game Five to win their second consecutive championship.

Unusually for him, Pearson started slowly in 1938, but in late June he began what would be a streak of ten consecutive wins. The final game of that streak was on August 27 in the nightcap of a doubleheader in the Bronx against Cleveland. Despite pitching on only two days rest, he was perfect through three innings. In the fourth, he walked the first two hitters but then sandwiched strikeouts of Jeff Heath and Hal Trosky around a groundout by Earl Averill. He set down the Indians in order in each of the next four innings. The Yankees’ potent offense, meanwhile, produced 13 runs, so the only suspense going into the ninth was whether Pearson would complete the first-ever no-hitter at Yankee Stadium.

“The ninth was the supreme succession of thrills,” noted one account.34 Pinch-hitter Moose Solters struck out on three pitches. The next batter, Frankie Pytlak, hit a slow roller that looked like trouble but “Joe Gordon made a great play on it and the ball beat Pytlak by a step.”35 The Indians’ last hope was Bruce Campbell, who lined out to Selkirk, and Pearson’s gem was complete.36 Perhaps his most difficult challenge of the day was fighting his way past celebratory fans to reach the clubhouse after the game.37

Pearson finished the year with a 16-7 record and 3.97 ERA to help the Yankees claim their third consecutive pennant. (He also became a father again with the birth of his daughter, Anita, in September.)38 Reports at season’s end suggested Pearson might not pitch in the World Series due to an ailment.39 Once again, though, he recovered in time to turn in a dominant performance, this time against Chicago in Game Three, as he limited the National League champs to five hits in a complete game 5-2 win. “Pearson showed us more than any other pitcher,” said Cubs player-manager Gabby Hartnett. “Where does that guy get all that stuff? I’ve seen some pretty good curve ball pitchers, but that fellow certainly can make the ball duck over the corners.”40 The Yankees completed their sweep of the Series the next day.

Pearson started strong in 1939 but struggled later in the season. He blamed his troubles on a tired arm, but doctors were unable to diagnose a problem: inevitably, the old doubts about his competitiveness resurfaced.41 As the Yankees cruised to their fourth straight pennant, there was speculation that Marius Russo might move into the World Series rotation “[w]ith Monte Pearson a big question mark [based] on his bad performances in the last two months and his imaginary sore arm.”42 As he had so many times before, though, Pearson recovered in time to secure a World Series assignment, this time a Game Two start against Cincinnati.

After the Yankees won a Game 1 pitching duel, Reds manager Bill McKechnie expressed confidence that his club would rebound. “One game don’t win a series,” he said. “The Yanks are no super ball club. They can be beaten, and I’ll send Bucky Walters after them tomorrow.”43 Walters had won the NL Most Valuable Player Award with 27 wins and a 2.29 ERA compared to Pearson’s 12-5 mark and ERA of 4.49.

But it was Pearson who that day would pitch one of the greatest games in World Series history. In front of almost 60,000 at Yankee Stadium, he was perfect through three innings; issued a walk to Billy Werber (who was then caught stealing) in the fourth; then threw three more perfect innings. As the eighth began, the Yankees had a 4-0 lead and Pearson had yet to allow a hit. He went to work “as a throng of …fans sat tensed and ‘oohed’ and ‘aahed’ with every pitch.”44 Frank McCormick led off and flied out to Selkirk in deep left field. With 7 1/3 hitless innings, Pearson had now tied the Series record set by the Yankees’ Herb Pennock in 1927.45

Next up was Cincinnati’s hard-hitting catcher, Ernie Lombardi. Pearson and Lombardi knew each other well, as they had been battery mates with Oakland in 1930. That familiarity hadn’t helped Lombardi in his first two at bats, but this time he lined a clean single over second base. Pearson retired the next two hitters on a strikeout and a weak groundball. He gave up only a two-out single in the ninth before completing the two-hit shutout. “I just kept bearing down on one batter just as hard as I did on the other… My only object was to get those Reds out as fast as I could,”46 said Pearson of his masterpiece, which took only 87 minutes. While Pearson’s performance was recognized as brilliant, some writers used the opportunity to reiterate what they perceived as his failure to make the most of his talent. “Among some baseball writers, Pearson is considered a hypochondriac and a front runner. I’m not prepared to indorse either suspicion,” wrote columnist Ed McAuley. “But it does seem safe to say that a man who can pitch as brilliantly as Pearson did yesterday . . . hasn’t made the most of his equipment when he has averaged only 13 victories a year.”47

The Yankees won the next two contests to sweep the Reds for their fourth consecutive championship. As was his custom, Pearson returned to Fresno and spent considerable time hunting during the 1939 off-season, even missing DiMaggio’s wedding for a hunting trip.48 One such expedition nearly ended in disaster, as a fellow hunter barely missed shooting Pearson in the head. “The blast from the shotgun tore a hole along the side of Pearson’s close-fitting cap but the world series star escaped with no injury except a small bump over the left ear where a pellet grazed him.” 49

At spring camp in 1940, The Sporting News considered it noteworthy that Pearson had “gone through a training season without mishap or a severe cold for the first time since he came to the Yankees…”50 He started strongly, earning an All-Star berth with a 6-4 record and a 3.32 ERA through June.51 The Yankees, though, struggled, and were in fourth place on July 17 when Pearson took the mound against the Cleveland Indians and Bob Feller. In what turned out to be his last great performance, Pearson threw a 13-inning complete game to beat Feller, 4-3: but in the process he tore a ligament in his right shoulder.52 Save for an ill-fated comeback attempt that lasted less than an inning, Pearson was done for the season.

After the Yankees failed to repeat as pennant winners, General Manager Ed Barrow made a number of personnel moves, including sending Pearson to the newly crowned World Champion Cincinnati Reds for “a substantial” chunk of change and infielder Don Lang. Though Cincinnati acknowledged that Pearson was an injury risk, manager Bill McKechnie’s reputation for coaxing strong performances from veteran pitchers was cited as a likely factor behind the deal. 53

Pearson—whose third child Larry was born a couple of months before the trade–expressed enthusiasm for his new situation. “It’s great to be . . . managed by a swell fellow like Bill McKechnie,” he said. “I’m going to prove to a lot of those American Leaguers that old Monte is far from being a sore-armed, washed-up pitcher.”54 But it wasn’t to be. Pearson’s arm problems resurfaced 55 and he threw fewer than 25 innings before the Reds sold him outright to the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League.56 He managed only one PCL appearance before shutting it down for the season.57

After initially planning to return to baseball in 1942, Pearson announced that he would instead take the year off in hopes that his arm would recuperate. 58 He was rejected from the military due to his injury, so instead worked as a firefighter at a military base near Fresno 59 while also playing second base in a semi-pro league.60 But his arm never improved, and in August he announced his retirement from professional baseball.61 His final major league line included a 100-61 won-loss record, a 4.00 ERA, a .228 batting average in 513 at-bats, two All-Star selections, and four World Championships.

Over the next couple of years, Pearson played in local leagues and made noises about a possible comeback, but it never materialized.62 In the meantime, he announced he was taking up competitive boxing. “He is only doing this to keep active, no money involved,” stated his trainer, who noted that Pearson was fiscally prudent and owned nine separate revenue-generating properties to supplement his $195 monthly firefighting salary.63

In the mid-1940s Pearson decided to attend the University of California, Berkeley, graduating with a degree in Public Health.64 Though he didn’t play baseball at Cal, he did tell Oakland Oaks manager Casey Stengel that he would be happy to pitch batting practice to his former club: there’s no record of whether or not Stengel accepted his offer.65 After finishing up at Cal, Pearson was hired by the City of Fresno as a sanitarian. For the next several years, he was a regular speaker at PTA meetings, sports-related gatherings, and fraternal organizations. He had always enjoyed music–he played guitar and sang in a quartet with teammates Joe Gordon, Tommy Heinrich, and Paul Schreiber66—and now he sometimes performed at City events. 67 For several summers, he also led the Fresno Bee’s annual summer baseball school.68

Given Pearson’s seeming desire to remain in the spotlight, it was perhaps unsurprising that he announced in 1952 his candidacy for County Supervisor. He was the top vote-getter in the June election, but didn’t secure the necessary 50% threshold to avoid a November runoff, which he ultimately lost.

In 1953 he left Fresno to become the Chief Sanitarian in nearby Madera County.69 His persona was that of an honest, hard-working public servant, but in May 1962, a bombshell hit the papers: Pearson had been indicted for having demanded bribes to approve improperly installed septic tanks. The District Attorney said the companies involved had installed 100-200 septic systems incorrectly and they were a threat to the public health.70 Pearson was found guilty of one felony bribery count and sentenced to eight months in jail plus three years’ probation.71 He and Cleo divorced a few weeks later, just before he started his jail term.72 Ironically, his oldest son Wesley, who had become a Deputy Sheriff, served as one of his jailers.73 Subsequent to his jail term, Pearson in 1964 petitioned successfully to have his probation terminated and conviction set aside. 74

Pearson married the former Nellie Slayton in 1964. His granddaughter Tammy Alexander remembers going to their home in Fowler, in Fresno County, where her grandfather taught her and her siblings not only how to play baseball, but also how to hunt. “I didn’t realize how famous he was,” she said. “But I thought grandpa was cool. He was funny, always joking around.”75

In 1967, Pearson was elected to the Fresno Athletic Hall of Fame.76 There were many outside the Fresno area who also remembered him. In 1970, Ted Williams was asked what he thought of a rookie pitcher named Bert Blyleven. “He’s so smooth,” said Williams. “He reminds me of Monte Pearson. Remember Monte Pearson? He was one helluva pitcher and everything he did was smooth. That’s who this Blyleven kid reminds me of a lot.” 77

Pearson worked in real estate in the Fresno area in the 1970s. But toward the end of the decade, his health began to fail, and on January 27, 1978, he passed away of cancer at the age of 69 and was buried at Washington Colony Cemetery in Fresno.78 His obituary referenced his injury history and his later-in-life legal troubles; but it also reminded baseball fans of Pearson’s extraordinary World Series performances, a record of accomplishment that to this day ranks him as one of the greatest post-season pitchers in baseball history.79

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Paul Proia, Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team. Thanks also to Tammy Alexander for sharing her memories of her grandfather, and to Arnold Hano for his crystal clear recollections of Game Four of the 1936 World Series.

Notes

1 California Birth Index and Social Security Death Index retrieved using Ancestry.com. Sources differ regarding Pearson’s birth year and even his birth name. His Hall of Fame file and many newspaper articles give his birth year as 1909, as does his World War II draft registration card; and some sources such as Baseball-Reference.com give his birth name as Montgomery Marcellus rather than Marcellus Montgomery.

2 “Monte Pearson’s Platform Favors County Manager,” Fresno Bee, April 6, 1952: 13. Also, “Death Makes Five Children Fatherless,” Tonopah Daily Bonanza, April 15, 1910: 2.

3 Ancestry.com. Also, “Death Makes Five Children Fatherless,” Tonopah Daily Bonanza, April 15, 1910: 2; and “Pearson, World Series Star, Dies in Fowler,” Fresno Bee, January 28, 1978: B1, B2.

4 Jack Perry, “Why and How,” Fresno Morning Republican, September 16, 1931: 11.

5 Frederick Lieb, “Pearson, Near 30-Mark, Improves With Age to Keep Lively Pace Set by Yankee Mound Staff,” The Sporting News,” June 1, 1939: 3.

6 Lieb

7 Eddie Murphy, “Pearson Bought From Oaks by Cleveland,” Oakland Tribune, September 15, 1931: 32.

8 “Monte Pearson Shows Up Well,” San Bernardino County Sun, March 9, 1932: 12. In later years, Pearson became known as more of a curveball specialist.

9 Henry Edwards, “Pearson Had too Much Speed for Third Sacker; Became Moundsman,” Shreveport Times,” March 18, 1934: 16.

10 “Hens Win First Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 24, 1933: 14.

11 “Eddie Morgan Sent to Pels by Cleveland,” Mansfield News-Journal, July 3, 1933: 10.

12 https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/earned_run_avg_plus_season.shtml. Accessed March 14, 2021. To qualify for the leaders list, baseball-reference requires that a pitcher throw at least one inning for every game played by their team that season. Pearson had 135.1 IP while the Indians played 151 games in 1933.

13 Dick Farrington, “Stellar Group of Recruits Became Major Regulars in ’33,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1933: 3. Other members of the all-rookie team included Hall-of-Famers Joe Medwick and Hank Greenberg.

14 Ed Orman, “Sport Thinks,” Fresno Bee, October 11, 1933: 14.

15 Ed Hang, “Tribe Uses Hurlers to Draw Out Offers,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1935: 3.

16 Bang

17 Ed Bang, “O’Neill’s Yankee Deal Opens Door to Wolves,” The Sporting News, December 19, 1935: 2.

18 Frederick Lieb, “Pearson, Near 30-Mark, Improves With Age to Keep Lively Pace Set by Yankee Mound Staff,” The Sporting News,” June 1, 1939: 3.

19 Lieb

20 “Pearson Is Happy to be on Yank Club,” Fresno Bee, December 12, 1935: 17.

21 Stuart Rogers, “Pearson Stricken While A’s Win, 4 to 3,” New York Daily News, September 25, 1936: 49. Other sources suggest that Pearson was laid up with the flu. See Richard Tofel, A Legend in the Making: The New York Yankees in 1939,” (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2002), 72.

22 Frank Reil, “Mental Hazard May Keep Monte Pearson Off Mound in Series,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 29, 1936: 18.

23 “Hopes of Yanks Receive Blow as Monte Pearson Is reported Unlikely to Start Single Tilt,” Glen Falls Post-Star, October 1, 1936: 12.

24 https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/carl-hubbell/. Accessed May 8, 2021. Hubbell went on to win his first eight decisions in 1937 for a regular season streak of 24 consecutive wins spread over two seasons.

25 Damon Runyon, “Yanks Blast Giants for 5-2 Win,” Miami Herald, October 5, 1936: 8

26 Arnold Hano, telephone interview, February 28, 2021. See also Hano, Arnold, “A Day in the Bleachers,” (New York, Cromwell, 1955), 8. Hano’s classic account of Game 1 of the 1954 Series includes a brief reminiscence in Chapter 2 of his day in the bleachers at the 1936 Series.

27 Hano. His recall of details of a game 84 years after the fact was astounding.

28 “McCarthy Looking for More Cripples Like Monte,” Brooklyn Times Union, October 5, 1936: 11.

29 Arnold Hano interview.

30 Jack Smith, “Pearson Injures Ankle in Practice,” New York Daily News, March 9, 1937: 542.

31 “Bees Tie Dodgers…Hub on 25th…Gomez Drops NRA,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 31, 1937: 6.

32 Jack Smith, “Hero or Goat? Series Will Tell,” New York Daily News, October 3, 1937: 37.

33 Elliott Cushing, “The Winner? Only Yanks, To Selkirk,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 3, 1937: 20.

34 Sid Mercer, “Yanks Take Opener, 8-7, and Nightcap, 13-0,” New York Journal-American, August 28, 1938: 14.

35 Mercer. Pearson had some history with Pytlak. The two had been battery-mates for much of Pearson’s time with Cleveland; then in 1936, Pearson’s first season with the Yankees, he hit Pytlak in the jaw, breaking it in three places. See https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/frankie-pytlak/.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 “Monte Pearson Becomes Father for Second Time,” Fresno Bee, September 12, 1938: 10.

39 “Yankees Boast Pitching Edge in Big Series,” Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, September 30, 1938: 5.

40 Frederick Lieb, “Pearson, Near 30-Mark, Improves With Age to Keep Lively Pace Set by Yankee Mound Staff,” The Sporting News,” June 1, 1939: 3.

41 “Pearson’s Arm Series Worry,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 8, 1939: 18.

42 “Russo No. 3 Series Hurler?” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 22, 1939: 18.

43 “Reds Boss Not Disheartened,” Wilkes-Barre Record, October 5, 1939: 14.

44 Associated Press, “Pearson’s Superb Hurling Paces Yanks to Second Win,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix), October 6, 1939: 14

45 AP

46 “Yank Ace Kept Bearing Down,” Wilkes-Barre Record, October 6, 1939: 27

47 Ed McAuley, “Pearson Deserves These Superlatives But . . .” The Sporting News, October 12, 1939: 9.

48 “Happy Mr. and Mrs. Joe DiMaggio Spend Honeymoon in Fresno,” Fresno Bee, November 21, 1939: 11. DiMaggio didn’t sound offended that Pearson had declined the wedding invitation, calling Pearson “one of the swellest fellows in the game.”

49 “’High and Outside’ Gunshot Barely Misses Head of Monte Pearson, Fresno Bee, December 4, 1939: 10.

50 Fresno Bee

51 As in 1936, Pearson was selected to the All-Star team but did not pitch.

52 Fan Fare, Washington Post, January 28, 1978: page unknown. Clipping from Pearson’s file at the Baseball Hall-of-Fame.

53 Tom Swope, “M’Kechnie Playing Hunch on Pearson, The Sporting News, January 2, 1941: 5.

54 “Reds to Face Cards Today; Monte Pearson Hard Worker; Lom Due at Camp Tonight,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 12, 1941: 17.

55 “Monte Pearson Now Is Question Mark,” Cincinnati Enquirer,” April 2, 1941: 18.

56 “Hollywood Buys Monte Pearson to Bolster Club,” Fresno Bee, August 22, 1941: 12.

57 “Film Nine is Routed by Seals,” Long Beach Sun, September 2, 1941: 13.

58 “Pearson Will Not Pitch for Reds This Year,” Fresno Bee, April 18, 1942: 8.

59 “Monte Pearson’s Platform Favors County Manager,” Fresno Bee, April 6, 1952: 13.

60 “Bits of Action in Fresno’s Twilight Baseball League,” Fresno Bee, July 5, 1942: 13.

61 “Monte Pearson Says He’s Through in Majors,” Montgomery Advisor, August 28, 1942: 12.

62 Lee Dunbar, “On the Level,” Oakland Tribune, May 23, 1945: 14.

63 Russ Newland, “Newland’s Sports Gossip,” Fresno Bee, August 17, 1943: 13. Pearson appears to have thought better of taking up prizefighting, as there is no record in the Fresno papers of his participation in an actual bout.

64 Mike Konon, “Ace Pitcher Pearson’s Launching Son Larry Into Big-Time Ball,” Madera Tribune, February 18, 1960: 9.

65 “Oaks Play at Home,” Valley Times,” March 21, 1947: 10.

66 Jimmy Powers, “The PowerHouse,” New York Daily News, February 20, 1940: 349.

67 “Band Will Appear for Freedom Bell Show Tomorrow, Fresno Bee, September 10, 1950: 25.

68 “Monte Pearson Will Head Staff of Four Experts at Bee-KMJ Baseball School,” Fresno Bee, July 3, 1949: 17.

69 “Pearson is Named,” Fresno Bee, September 13, 1953: 25.

70 “Pearson is Indicted on Bribery Counts,” Fresno Bee, May 16, 1962: 4.

71 “Pearson Gets Jail Term for Accepting Bribe,” Fresno Bee, December 6, 1962: 1.

72 “Monte Pearson is Divorced on Cruelty Ground,” Fresno Bee, December 27, 1962: 25.

73 Tammy Alexander, telephone interview, March 26, 2021.

74 “Pearson’s Probation is Terminated By Court,” Fresno Bee, July 4, 1964: 12.

75 Tammy Alexander interview.

76 “Five More Win Berths in Fresno Hall of Fame,” Fresno Bee, November 16, 1967: 29.

77 Milton Richman, “Holland Hummer, 19, Smooth Like Monte Pearson,” Dayton Daily News, June 27, 1970: 5.

78 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/156776780/monte-montgomery-pearson; accessed May 22, 2021.

79 “Obituaries: Monte Pearson,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1978: 65.

Full Name

Montgomery Marcellus Pearson

Born

September 2, 1908 at Oakland, CA (USA)

Died

January 27, 1978 at Fresno, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.