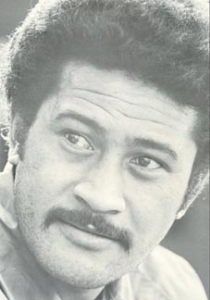

Tony Solaita

Fa’a Samoa – The Samoan Way – is an ethic that embraces a community. Its central tenets are respect for elders, religious faith, and unshakable family loyalty. Aiga, perhaps best translated as clan, guided the life of Samoa’s sole major-leaguer: Tolia “Tony” Solaita.

Fa’a Samoa – The Samoan Way – is an ethic that embraces a community. Its central tenets are respect for elders, religious faith, and unshakable family loyalty. Aiga, perhaps best translated as clan, guided the life of Samoa’s sole major-leaguer: Tolia “Tony” Solaita.

Tolia was born in the village of Nu’uuli, on the main American island of Tutuila. He was the fourth of seven children born to Tulafono Ioane Solaita and Lili’aifao Maugalei Soliai Solaita. Tulafono, who passed away in June 2000 at the age of 81, upheld the old traditions as a matai or village chief (with the honorific Levu). The patriarch always told his five boys and two girls, especially when they came to the United States, “You don’t need friends – your brothers and sisters are your friends.” In particular, Tolia and his two-years-younger brother Peni “Ben” Solaita were inseparable.

Ben (who died in 2011) eventually became president of the American Samoa Baseball Association and president of the Olympic Committee. After Tony was murdered in a dispute over land in 1990, genial Ben carried on his brother’s memory as no one else could. Although there have been many top-notch Samoan athletes, especially in football and rugby, only later did pesipolo build a following. The brothers Solaita deserved top credit.

As a small boy, Tony played the game of Samoan cricket, or kirikiti. Indeed, it may be why he was always a good low-ball hitter. Although American sailors and soldiers had played baseball at various points, it never really took hold. Ben Solaita thought one of the reasons was that “If you broke your bat or lost your ball, you had to wait for another American to come along and bring a new one.” Besides, kirikiti had become rooted in local sporting life. The British, under consul William B. Churchward, introduced the original game around 1883. In his memoirs, Churchward described how the natives modified cricket, sometimes making it a week-long party matching one town against another. Kirikiti, with its difficult-to-control three-sided bat, remains popular not only in Samoa itself but also in transplanted communities such as Seattle.

Tony was first introduced to baseball at the age of eight in 1955, when his family moved from their little sugarcane and banana plantation to Hawaii.[1] Actually, his father had gone ahead four years previously, saving up money to bring over the rest. Tulafono was a member of an elite Samoan unit called the Fita-Fita Guard, which was established in 1900 by the first U.S. governor of the territory, naval commandant Benjamin Franklin Tilley. On Flag Day, April 17, 2000, the Guard helped celebrate American Samoa’s centennial.

The Solaitas were one of the first families to emigrate – indeed, English was still not widely spoken there, despite several decades of U.S. government effort. Tulafono joined the Marines, successfully arguing that his service with the Fita-Fita should count toward his tenure. After 23 years, he retired as a master sergeant.

In Hawaii, Tony went with his cousin to Little League practice. He was shown how to run the bases and not to grip the bat cross-handed.[2] Recalling his first game, Tony said, “the manager gave me an old glove and put me at second base. I felt awkward with the glove and, after a while, threw it off and played barehanded. My hands were tough from playing cricket… But I knew from the start I loved the game of baseball. That’s all I wanted to do.”[3]

The Marine life caused the Solaitas to move to Oceanside, California (near San Diego) in 1957. Three years later, it was off to San Francisco. Around that time, Ben noted, older brother Tulafono Jr. could have become the first Samoan pro in baseball. “He was a great athlete too. He went to a Giants tryout camp and was one of five guys they invited to their minor-league camp out of a group of five hundred. But he was always screwing around. We put him on a bus for Phoenix and we found out he got off in San José!”

As a schoolboy, Tony would walk four or five miles with future Cardinal Ken Reitz to play ball, carrying equipment down the freeways.[4] They were part of a crowd that would seek out a game in any uneven empty lot. Ben remembered, “We used to play a game called ‘Strikeout’ with one pitcher and one hitter. We’d draw a box for the strike zone on the stucco wall of the school, and there were 16 boxes, that’s how many pairs we had. Kenny Reitz, who was a little younger, we called ‘Radar’ because his ears stuck out, which ticked him off! There were these rubber balls with seams painted like a hardball, they cost 29 cents apiece. Each guy would kick in a buck and buy three balls, and we’d play all day. We’d cut out the box scores from the previous evening’s games and pretend to be big-leaguers. All that ‘Strikeout’ was how our arms got strong and why we became such good hitters.”

At Jefferson High School in Daly City, a San Francisco suburb, Tony Solaita was Athlete of the Year as a senior, winning a total of eight letters as captain of both the baseball and football teams. He abandoned the latter in part because of injuries to his ankles, but his heart was on the diamond rather than the gridiron.

Tony was also a pitcher for Jefferson, once throwing a no-hitter. But it was really his hitting that attracted attention. The young first baseman had grown to a remarkably powerful six feet even, 210 pounds when Dolph Camilli saw him. The Brooklyn Dodgers star of the ’40s was a scout for the New York Yankees out in the Bay Area. He and a Giants scout vied to sign Tony. But if Tulafono Sr. (who was also Methodist minister to a Samoan congregation) hadn’t been a man of such strict principles, more money might have been offered. As Ben told it:

“Our father really didn’t know about negotiations. He decided that each team would get the chance to make one bid, and that was it. Camilli and the other guy, whose name is on the tip of my tongue, came over to the house, and the Giants had the bad luck to go first. So Camilli offered $1,000 a month and a $500 bonus, and it was a done deal!”

When Tony began his pro career in 1965, he didn’t show his power for a couple of years, although his .324 mark led the Gulf Coast League in 1966. But the next year he lifted his home run total to 14, and he also delighted his teammates in Fort Lauderdale with a Samoan skill. “They couldn’t believe I could climb coconut trees. So I got them together, shinnied up one, and brought them back some coconuts. They were amazed.”[5]

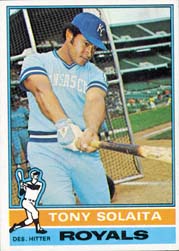

In 1968 came the breakthrough. Tony joined High Point-Thomasville in the Single-A Carolina League, playing under career baseball man Jack McKeon. He clouted 51 homers for the Hi-Toms, including two in the playoffs – more than any other player in Organized Baseball. Solaita was voted Topps Minor League Player of the Year, and his reward was a chance to play at Yankee Stadium.

Tony was so excited that he spent $47 on a 15-minute call to his parents, who were vacationing back in Samoa. The friendly Polynesian also endeared himself to the local kids, who would follow him all the way from the ballpark to his hotel.[6]

Wearing #51, Solaita raised hopes that he would become the newest Bronx Bomber when he won a home run hitting contest over five accomplished big-league sluggers – Reggie Smith, Ken “Hawk” Harrelson, Carl Yastrzemski, Rocky Colavito, and Mickey Mantle himself. Tony hit four of 10 pitches out, and another drive that was barely foul almost left the stadium, hitting the facade.[7] He got one taste of game action, replacing Mantle for four innings in Detroit. Despite some serious baptismal jitters, he played the field without incident, but struck out in his only at-bat against John Hiller.

Tony would not resurface in the majors, however, until five more seasons had gone by. “The Yankees screwed him up,” said Ben. “They put him on the 15-man protected list for the [November 1968] expansion draft, built him up as the next Mickey Mantle, and then they buried him.” Jack McKeon had joined the new Kansas City Royals organization as manager of their Triple-A club, Omaha. According to Ben, he had promised the first-base job to Tony, but to do so was not within his power.

One cannot really blame New York for hanging onto a good-looking prospect, and the Royals would also have had to contend with the three other new teams. Even so, the Yankees organization did treat Solaita like a stepchild. Whereas they had their own Carolina League club, High Point was a co-op, stocked by several franchises. Tony also played most of the 1969 season on loan to two White Sox farm clubs. He then returned to the top Yankees affiliate, Syracuse, but did not get the callup he fully deserved in 1970.

The disappointment may have affected Tony mentally, because 1971 was a sub-par year. Although he could not fulfill a wish to buy his father and flock a new church, to “have done something for God,”[8] he married sweetheart Faga Alailima that December. Faga told the story of how the couple met.

“My father was a Methodist minister too, but he was in Los Angeles. Twice a year there were these church get-togethers, and we first saw each other at one in Oceanside in 1970. We just said ‘hi’ then, but at the San Francisco gathering in January 1971, my parents stayed at his parents’ house, and then we got to talking. The next thing I knew, I thought he was just kidding, but he wasn’t at all – he came down to our house and asked my father if we could get married! Then he left for spring training, and at the end of the season, we talked about our wedding.”

Still, even that lift did not help him avoid a poor start in 1972. The Yankees demoted Solaita to Double-A, and he was thinking about quitting. A plethora of other contenders blocked him, including Brooklyn boy Frank Tepedino and the #1 overall draft pick of 1967, Ron Blomberg – who was also favored as a would-be Jewish drawing card, something New York teams have sought since the days of John McGraw.

In February 1973 Tony was traded to the Pittsburgh chain for 14-year minor-leaguer George Kopacz. With the Charleston Charlies, he got his career back on track, and then the benevolent Jack McKeon interceded. McKeon had moved up to manage the Royals that year, and in December they drafted Tony off the Charleston roster. The manager would later state, “Tony ranks among the top two or three players I have managed when it comes to on- and off-the-field considerations.”[9]

The $25,000 wager turned out to be a good one – at age 27, Solaita made the majors to stay. He backed up John Mayberry at first and also saw time at designated hitter. Some of the homers he hit were blasts to rival any of the greats, including one off the facing of the upper deck at Shea Stadium and another that carried to the roof in right-center at Tiger Stadium. Reggie Jackson had hit a famous shot off the light tower there in the 1971 All-Star Game, but Tony’s ball – estimated at 550 feet – was hit into the wind. During 1975, he had 16 homers in 231 at-bats, the best ratio in the AL and second only to Dave Kingman in the majors. On September 7 that year, Tony became the first player to hit three in a single game at Anaheim Stadium, driving all of them over the centerfield fence. In attendance was Faga (who was visiting her sick mother), along with her brother and Tony’s sister.

At the same time, though, big John Mayberry had his career year, while Whitey Herzog took over for McKeon in late July. Mayberry was injury-prone and inconsistent, but he was also better with the glove, even though Tony was by no means a liability in the field. In addition, the Royals were still giving Harmon Killebrew (in his last season) most of the time at DH. After about a year, Herzog decided not to carry another lefty 1B-DH, and so Tony was sold to the California Angels. “But he never said he had any bad feelings about anyone,” noted Faga. “That’s the kind of person he was.”

Though he missed a chance to go to the playoffs, near the end of the 1976 season, the Angels staged a “Samoan Salute to Tony Solaita” with pregame entertainment by Polynesian dancers and musicians. It was also a savvy PR move, what with the 40,000-strong Samoan community in Southern California![10] (Already there were more of them in the U.S. than in the islands.) Samoans were offered two tickets for the price of one, and Ben Solaita remembered that busloads of countrymen came up from their former hometown of Oceanside, where Tony had also attended Mira Costa College. Ben kept the home movies he took that day.

That winter, Tony benefited once again from Jack McKeon’s good offices. McKeon went to the Puerto Rican Winter League to manage the Santurce Cangrejeros, and offered Tony playing time against lefthanders, which he had seldom gotten before. It was a good experience, as seven of Solaita’s 11 homers in Puerto Rico came off southpaws.[11] That was his only season in winter ball, however, as he felt that playing year-round was too much of a grind.

Unfortunately, Tony was not able to break out of a platoon with Ron Jackson during the next major-league campaign. He did play in 116 games and got 324 at-bats, both career highs, but his 14-53-.241 stats were just fair. And in 1978, he fell out of favor, hitting .223 in just 94 AB. Pitcher Mike Flanagan, in a clever but cutting quip, called him “Tony Obsolete-a.”

Tony split the 1979 season between the Montreal Expos and the Toronto Blue Jays (where he once again backed up John Mayberry). He produced rather well in spot duty, but the Jays made him a free agent. So early in 1980, he signed a multi-year offer to play in Japan – where the financial rewards were often the best of the day – and embarked on a new phase of his career.

During his four years as DH with the Nippon Ham Fighters, Tony posted prodigious power numbers, averaging 39 home runs and 93 RBIs per 130-game season. On April 20, 1980, he became only the second player to hit four straight homers in a Japanese game – the first was the great Sadaharu Oh. He was most impressive in 1981, tying for the Pacific League lead with his 44 HR and winning the RBI title with 108. In the second half of the split season, Tony had 14 of his 17 game-winning hits, and he led the Fighters to only their second Pacific League pennant in franchise history. He hit two homers as Ham took a 2-1 lead in the Japan Series, but the perennial power, the Yomiuri Giants, wound up winning.

As did many gaijin (foreign) players, however, Solaita had to contend with culture clash. Robert Whiting, the leading writer in English on besuboru, studied this theme in his book You Gotta Have Wa. Several stories featuring Tony – “perhaps the strongest person ever to play baseball in Japan” – showed how this collision could be entertaining and sobering by turns. Many episodes featured the least attractive side of the Japanese game – naked bias and xenophobia. When Tony broke the Fighters club record for homers in a season in 1980, nobody in the organization told him about it, much less congratulated him on it. Despite carrying the team’s offense during the pennant year, he finished a distant third in the MVP voting. A Nippon Ham front-office official said, quite candidly, “If Solaita had been Japanese, he would have won it easily.”

In 1982, when Tony was battling for the home run crown with Hiromitsu Ochiai of the Orions, opposing pitchers began intentionally walking him all the time. Tony refused his manager’s offer to retaliate in kind as unprofessional, but in his last plate appearance of the season, he removed himself. Whiting recounted some other tales of how frustrating Solaita found Japan at times. Normally he was unhurried and friendly, but he was also prone to violent outbursts of temper. Late in the 1983 season, when he knew he was going to be released, he threw the team’s 6’ x 3’ message board out of a hotel window.[12]

Faga laughed when told that story. “I didn’t know about that one! I left before the end of the season. But I wouldn’t blame him for it. Who wouldn’t have a temper in Japan? So many times when we were there, he got really, really frustrated. It was hard for Tony to do his work like he used to do in the States because he was an honest ballplayer and tried to do his best. They told him to strike out, even if he knew he could hit a guy. And I saw this with my own eyes. They fined him for not doing what they wanted, and Tony hated that. He said ‘I can’t do it! I came here because I love the baseball game, I came to play.’”

Tony chafed at another military aspect of the way the game was run. “The family couldn’t ride on the same train with the team, but he wouldn’t take it, and so they’d fine him for that too! Japan really was a different story. For the first year, it was nice, we enjoyed it. As a guest, they’ll treat you like a V.I.P. there. And Tony got pretty good with Japanese, he was the kind of person who liked to learn. Not me, I only knew words to do the food shopping and take the taxi to the ballpark! But the last few years, it wasn’t the same.”

The San Francisco Giants showed interest in having Tony come back to the U.S. and play for them in 1984. But working out with Ben that winter, he told his brother that baseball had become a job, it was no longer fun. So at age 37, Tony Solaita retired.

Following the funeral of their grandmother in Hawaii, Ben and Tony made a seemingly innocuous decision – they decided to take a trip to Samoa. Amazingly, they had not returned since the family had left nearly 30 years before, although oldest brothers Milovale and Tulafono had moved back in the early 1970s. All Ben really remembered was running along the road, hitting a wheel with a stick, but what had always stuck in Tony’s mind was how the moon shone off the white sand. And when they got there, he fell in love with his native land. He told Ben, “This is the place for me.”

What had started out as a two-week vacation was transformed into a plan to move both families. At least that was Tony’s idea; Ben resisted strongly. “I told him I wasn’t interested, the place was too small. You drive a few minutes one way, there’s ocean, you drive the other way, there’s more ocean.” But Tony kept working on him and wearing him down, and the special bond they had shared since childhood was the prevailing factor. “Our father always told us we were a pair, we had to do things together.”

There was just one other little complication to deal with – telling their wives. “So we got back to California,” said Ben, “and I gave the news to my wife, Laufasa. And you should have heard what she said! So then I called Tony and asked him if he’d told Faga, and he’d cheated, he hadn’t gotten up the nerve yet! But they went along with what we wanted to do.”

Faga’s view: “We had three kids while Tony was still playing, and I wanted them to go to school in the States.” Once they moved, though, the family expanded to more traditional Samoan size with two new births. Also, Solaita had ideas for more than just his own children.

As far back as 1976, Tony had said, “I want to go back there and encourage the kids to play pro baseball. It’s a great way to make a living. If I worked with 100 kids and only one of them ever made it, the effort would still be worthwhile.”[13] Eight years later, he and Ben straight away started to realize the dream.

“There had been baseball for a couple of years around 1981 and 1982, but it didn’t really take hold. A man named Dean Dowell gave us land for the field that’s now got Tony’s name. We borrowed a Caterpillar from an Alaskan company, S&S Construction. We got a little carried away, actually – we took a little extra space, knocked over a telephone pole! So we spent the year 1984 preparing the field, and then in 1985 we started up the program. We asked vendors for donations, and over the next few years, we built up to 600 kids of all different ages.”

In 1987, Tony brought a squad of Little Leaguers to Taiwan, and the next year he led a Senior League team to Hawaii. His last trip off island, in 1989, was to take a Big Division team to Los Angeles to participate in All-Star games there. “Tony always felt that to improve in baseball skills and baseball knowledge you have to play in international competitions.”

In 1987, Tony brought a squad of Little Leaguers to Taiwan, and the next year he led a Senior League team to Hawaii. His last trip off island, in 1989, was to take a Big Division team to Los Angeles to participate in All-Star games there. “Tony always felt that to improve in baseball skills and baseball knowledge you have to play in international competitions.”

Solaita also found another athletic outlet – fautasi, or Samoan longboat crew. The Flag Day races in April each year are Samoa’s answer to the Henley regatta. The villages that can afford a boat hurl themselves into the grueling contest with vigor. As Ben described it, “These are 92-foot-long boats with 45 guys on the crew, and it’s a five-mile course on the open ocean, all-out power all the way for 20 minutes. Got to win – can’t accept losses.”

“The first time we saw it, we had just come off the golf course. We were ballplayers, we never had anything to do with water sports. But we saw the Flag Day race in 1985, and Nu’uuli came in second by three heads. We got so excited and we were so upset! So the next year, all four of us brothers signed up, and Tony led the training. He was 260 pounds going in, and he trimmed down to 200!”

“We won that year and again in 1988, with Tony as the captain. But in 1989, we had this U.S.-built boat, and it was a flop. The guy built it for stability instead of speed, and we came in last. Tony was so competitive, and he knew he was going to get so much ribbing in the village, but we just flopped over the side of the boat and laughed. That was the last year he raced.”

Toward the end of the decade Tony got a hankering to go back to the mainland and coach pro ball. This was perhaps a little surprising in light of how much he loved Samoa, the vital youth programs he had established, and the lengths to which both his family and Ben’s had gone – but as Ben noted, “It was wherever Jack McKeon was: the Padres. And by this time, you can tell we made our own decisions!” But the return to the pro ranks never came to pass.

Unfortunately, fate – in a uniquely Samoan form – took a hand. “In my heart, I still think about it,” Faga mused wistfully. “If we never came down, maybe Tony would still be alive today.”

(N.B.: The following three paragraphs are based on the recollections of Ben Solaita. For the other side of the story, see the Postscript.)

Much of the land in Samoa is communally held, and the ones who decide its use are the matai. When he came home in 1984, Tony was granted a plot on which he established a meat market. “He didn’t know anything about meat,” said Ben. “But he had a hard head. You couldn’t tell him anything once his mind was made up.” Some time thereafter, a character called Harry “Tapu” Taylor (also known as Avalogo) appeared on the scene. “He came from San Francisco, he had been on welfare there. And he was asking the chiefs, why couldn’t he get some land?”

When the decision didn’t go his way, out of spite, Tapu took to vandalism and other acts of petty mischief against the Solaitas. “There was a machine to dig septic tanks,” recalled Faga, “and Tony left our truck there so no one would touch it. This guy broke out the lights of the truck, and the second time he broke out the lights of our house.” Tony remonstrated with the chiefs, even giving Taylor the money from his own pocket to go back to California.

Then in February 1990, Tony saw that a pile of beams out behind his store had been wrecked, and he knew who was back. As Ben told it, on the evening of Saturday, February 10, “Tony went to see the chief out by Tafuna village, but he wasn’t in. Then he saw the guy across the street with a friend, who knew the guy had a gun but didn’t say anything. They argued, and as Tony turned to leave, the guy shot him.” Public Safety personnel found the mortally wounded Solaita by the side of the winding road to Ottoville. He was pronounced dead on arrival at the LBJ Tropical Medical Center, aged 43.[14]

Faga supplied the poignant details of Tony’s last day in this world. “After Hurricane Ofa, we were staying in government houses. Tony was working with the police department and the FEMA people to clean up. He was going to Manua Island to deliver food and supplies, but early that morning he came back and said he’d changed his mind. He woke up the kids and said, ‘Why don’t we have breakfast?’ We hadn’t had any good food that whole week because of the hurricane.”

“At the airport we met so many people that we knew, and we started talking. But before we came home, we passed the baseball field that he started for the kids. And Tony said, ‘Let’s go see the field!’ It looked really bad, and he thought ‘Maybe we should come back and work on the field.’”

“But we decided to work on our yard, and at the end of the day Tony said ‘Let’s have a barbecue for all the neighbors!” We fed them all. Then people who rented our place came by and said this guy did something. I said to Tony, ‘Can I go with you?’ Usually he would give in when I asked, but that day he said no. I repeated ‘No, I want to go!’ but he said ‘I won’t be long.’”

“Our oldest son was in high school, he went with a neighbor to take the boys to swim. He came back and saw his father’s truck, but Tony waved and told him to go home. It’s not even five minutes away. We were outside talking, and we saw the ambulance and police cars rushing to the scene, and I said ‘What’s happening?’ But I didn’t know it was Tony. The doctor came and looked at me, but he couldn’t say anything. Then Ben’s wife and another brother-in-law came, and that’s when I knew something was wrong.”

“If there was any justice, that son of a bitch would be dead too,” stated Ben. “But he plea-bargained and got out after seven years.”

Nonetheless, Tony Solaita’s legacy continued to grow. “The public here loves the sport,” said Ben. “Businesses love the sport and love to donate. The parents get involved. People here have confidence that the ones running the program are looking out for their kids and their betterment. We’re careful about the coaches – we get guys who are calm, don’t cuss at the players. The Pee Wee games, they play at night time, and the place is packed!”

And even more important is how Ben and many others have paved the road for young Samoan men (and women in softball) to play at the collegiate and perhaps even the pro level. The ASBA was established in 1991, forming numerous connections and building infrastructure. During the winter of 1993, the Tony Solaita Baseball Field was expanded and renovated, with a grand re-opening in March 1994.

It is quite plausible that a spot with as much bright athletic talent as Samoa will someday turn out another player with the special skills to make it to the majors. And in the meantime, the game is being played with a spirit that seems to be in short supply in the United States today. It all goes back to the values that Tolia Solaita’s father instilled in The Baseball Family of the South Seas.

Said brother Ben: “Baseball isn’t really part of Samoan culture, but the Samoan culture of respect is in baseball here.”

Postscript

More than 30 years later, the story of Tony Solaita’s final days remains extremely sensitive and complex. In 2023, Harry Taylor’s daughter Itagia presented her account. She pointed to a long history of corruption, both before and well after Tony’s death.

According to Itagia, the land in question was deeded as personal property to her paternal aunt/mother[15], also named Itagia. However, after her aunt/mother’s death, the younger Itagia’s sister engaged in a pattern of fraudulent transactions, renting out spots of land and promising deeds that she didn’t have. Harry Taylor came to American Samoa to investigate this fiduciary abuse.

Meanwhile, if the land was not communally held, then the presiding matai did not have the jurisdiction over the elder Itagia’s personal property in granting Solaita use of a site for his store.

Solaita allegedly threatened Harry Taylor’s life, so Taylor resorted to using deadly force in self-defense. He fled to San Francisco, was arrested there, and brought back to American Samoa. In view of Solaita’s folk hero status, hostility toward Taylor ran high – outside the jail, a lynch mob formed.

After serving his prison sentence, Harry Taylor returned to Tafuna to tend to his family’s land. He died in 2007 and is buried on the property.

Itagia Taylor depicts Tony Solaita as a victim of broad and deeply rooted corruption and greed. She observes that he paid the ultimate price for his furious temper – and agreed with Tony’s wife Faga about the cruel irony that coming back to American Samoa was what led to his death.

If anything good came out of the whole affair, it was this: the land that became the expanded Tony Solaita Baseball Field was expropriated from the Taylor holdings as restitution.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Ben and Faga Solaita for providing their memories (interviewed by telephone in 2000).

Additional thanks to Itagia Tapu Taylor for her input (via e-mail, May 4-12, 2023).

Photo Credits

Topps Company

Ben Solaita collection

Sources

In addition to those shown in the Notes, the author consulted:

Sid Bordman, “Solaita Gives Royals Pick-Me-Up at Gateway,” The Sporting News, July 27, 1974: 25.

Red Foley, “Solaita, Blomberg Pacts Drop Into Yank Mailbox,” New York Daily News, February 13, 1970.

David Lamm, “Solaita Swats 42 Homers; He’ll Probably Hit Samoa,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1968: 47.

George Vecsey, “Houk’s Plans for Yanks Hinge on How Much Mantle Plays,” The New York Times, February 28, 1969.

George Vecsey, “Slugger from Samoa Appears Marooned Again on Way to Bronx,” The New York Times, March 7, 1970.

Notes

[1] Associated Press, “51 Homers! Yanks Hope for Samoa the Same,” The Binghamton Press, March 16, 1969.

[2] Hy Goldberg, “Sports in the News,” The Newark News, March 3, 1969.

[3] Del Black, “Born to Cricket, Tony Now Loud Royal Chirper,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1975: 10.

[4] Black, “Born to Cricket.”

[5] Joseph Durso, “Solaita, Big Hitter from South Pacific, Bids for Starring Role in Yankee Cast,” The New York Times, September 24, 1968.

[6] Jim Ogle, “Solaita Delights Yanks – Swings Home-Run Bat,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1968.

[7] Goldberg, “Sports in the News.”

[8] Ray Buck, “Solaita Dreams of Bigs – And Church for Father,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1971: 49.

[9] Black, “Born to Cricket.”

[10] Dick Miller, “Samoa’s Solaita No. 1 Angel,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1976: 14..

[11] “Southpaw Slugger in a Righthanded Lineup,” 1977 California Angels Scorebook.

[12] Robert Whiting, You Gotta Have Wa, New York: Macmillan Publishing Company (1989): 138-139, 285-287.

[13] Miller, “Samoa’s Solaita No. 1 Angel.”

[14] “Tony Solaita Killed in Tafuna Shooting Saturday,” The Samoa News, February 12, 1990.

[15] The younger Itagia Taylor was a tama si’i, a child given for adoption under Samoan tradition to heighten status and family bonds.

Full Name

Tolia Solaita

Born

January 15, 1947 at Nuuuli, (American Samoa)

Died

February 10, 1990 at Tafuna, (American Samoa)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.