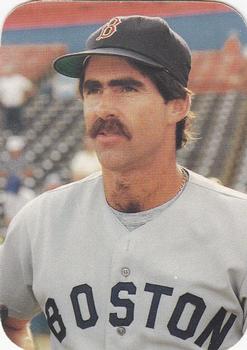

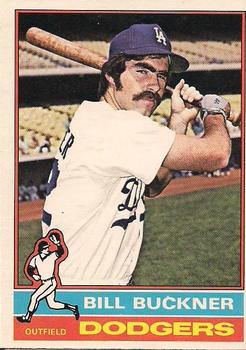

Bill Buckner

“GAMER 1. A player who approaches the game with a tenacious, spirited attack and continues to play even when hurt; a competitor; a player who doesn’t make excuses. The term is a compliment, most especially when it comes from another player.”1

Bill Buckner was a gamer. He played the game of baseball as hard as any player of his generation. Los Angeles Dodgers manager Walter Alston once said of Buckner, “He gets the red neck a lot, but I sort of like that.”2 Alston was referring to the fiery temper and intensity that fueled Buckner’s approach at the plate and in the field. Buckner detested strikeouts, which he considered failure. In nine different seasons he ranked either first or second in his league in at-bats per strikeout.

Bill Buckner was a gamer. He played the game of baseball as hard as any player of his generation. Los Angeles Dodgers manager Walter Alston once said of Buckner, “He gets the red neck a lot, but I sort of like that.”2 Alston was referring to the fiery temper and intensity that fueled Buckner’s approach at the plate and in the field. Buckner detested strikeouts, which he considered failure. In nine different seasons he ranked either first or second in his league in at-bats per strikeout.

To say Buckner played hurt is an understatement. He suffered a severe ankle injury in 1975 and never fully recovered. For the remainder of his career, he was forced to rely on a series of elaborate pregame rituals in order to force his body onto the baseball field. Chicago Cubs manager Herman Franks once remarked, “You should see this guy getting ready for a game. He rides that bike in there and does all kind of exercises. Then he goes in, and Tony (trainer Garofalo) tapes him from here to here.”3

A selfless player in an age of big salaries and bigger egos, Buckner was willing to switch positions when it meant improving the lineup and the club’s chances of winning. Before the ankle injury, he was a speedy outfielder capable of making outstanding catches. After the injury he gradually evolved into a full-time first baseman, making his last appearance as an outfielder in 1984. Over the course of his career, he played well over 600 games in the outfield and more than 1,500 games at first base. At the plate he possessed a compact swing capable of generating extra-base power to all fields. He won the National League batting title in 1980 and twice led the league in doubles. That he managed to do so despite lingering effects from the ankle injury is a tribute to his toughness.

His hustle and determination on the field brought with it the admiration and respect of teammates, opponents and those who merely watched him play. Columnist Dick Young once called Buckner “one of the guttiest players around today. He plays with a bad ankle, takes an aspirin and steals a base.”4 Buckner once cited Pete Rose’s style of play as an inspiration for his own and, like Rose, exuded immense confidence on the field. He set an example for his teammates to follow and sacrificed his body for the opportunity to play winning baseball. It is not an exaggeration to suggest that, were it not for the ankle injury, it might be easy to imagine Buckner having fashioned a career worthy of enshrinement in Cooperstown. He was one of the purest hitters of his generation, topping the .300 mark in seven different seasons.

William Joseph Buckner was born on December 14, 1949, in Vallejo, California. He was raised by his parents, Leonard and Marie Katherine Buckner, in American Canyon, California. His father died when Bill was a teenager. His mother worked for more than 20 years as a captain’s stenographer for the California Highway Patrol. In 1971 she remarried, to Harold Eugene McCall, a California Highway Patrol officer. Bill was raised with his three siblings, brothers Bob and Jim, and Jim’s twin sister, Jan. It was Marie who saw to it that the Buckner kids found their way into organized baseball. While attending a Cub Scout mothers meeting, she signed her boys up for Little League. “I thought it would keep them busy and out of trouble,” she recalled. “So they signed up. Their father was active in Little League with them, and they all used to practice in the living room. Even my daughter, Jan played softball in Napa and won a trophy to keep up with her brothers.”5 Bill was a natural athlete, and advanced for his age. As a seven-year-old, Marie falsified Bill’s birth certificate in order to get him into Little League a year early.6 He excelled from the beginning. His brother Bob, recalling Bill’s days in Little League, has said, “Pretty soon he was telling everyone what to do. Nobody could play the sun field, so he told the coach to put him out there. Here was this little kid with freckles showing everyone how to do it.”7 Even as a seven-year-old, Bill Buckner was intense. He probably got the “red neck” from time to time, back then, too.

Buckner was an A-minus student in high school who excelled on the gridiron as well as the baseball diamond. As a pass-catching end for the Napa High Indians, he compiled 963 receiving yards on 61 total catches, good enough to be named to the Coaches All-American team two years in a row. As a first baseman on the baseball team, he hit a whopping .667 in 1967 and .529 in ’68. Recalling high school, Buckner stated, “I was very goal-oriented. I was going to go to school and college, play sports, and go on to professional baseball. I didn’t spend a lot of time doing nothing.”8 He narrowed his college choices down to USC and Stanford. But his reputation as a hitter caught the attention of big-league scouts. Former New York Yankees second baseman and California Angels scout Joe Gordon recalled that Buckner “had the finest swing I saw anywhere on the West Coast, and probably is one of the best young hitters in baseball with his compact swing and power to all fields. He seems to have complete control of his bat and his body.”9 For the goal-oriented Buckner, college would have to wait.

The Los Angeles Dodgers selected Buckner in the second round with the 25th overall pick of the June 1968 amateur draft. That was a historically great draft class for the Dodgers, who managed to acquire 15 future major leaguers from among the four draft phases that existed in 1968. Bobby Valentine, Davey Lopes, Tom Paciorek, Doyle Alexander, Steve Garvey, and Ron Cey were among the young players who joined Buckner as new members of the Dodgers organization.

Buckner was assigned to the Ogden Dodgers in the rookie-class Pioneer League. His manager was Tommy Lasorda. Buckner played every game at first base, and recorded a .344 average in 275 plate appearances while swiping 15 bases in 16 tries. Paciorek, Buckner, and Garvey finished 1-2-3 in the batting race, propelling Ogden to the best won-loss record in the league. After the season ended, Buckner attended the University of Southern California, where he roomed with his Ogden teammate and roommate, Bobby Valentine.

Buckner began the 1969 season at Double-A Albuquerque, where he batted .307 in 70 games. On July 24 he was promoted to Triple-A Spokane to replace first baseman Tommy Hutton, who had been called up by the Dodgers to fill in for the injured Wes Parker. His .315 mark in 36 games led to a September promotion to Los Angeles. On September 21 Buckner pinch-hit for pitcher Jim Brewer and popped out to second base in a 4-3 loss to Gaylord Perry and the San Francisco Giants, his lone appearance for the Dodgers that season. After the season, Buckner batted .350 with 10 stolen bases in 46 games in the Arizona Instructional League. He played 38 games in the outfield, improving his chances to gain more playing time with the big club the following season.

Buckner was expected to compete for a roster spot on the Dodgers in 1970. Dodgers manager Walter Alston suggested, “It’s possible Bill could be our starting left fielder. He’ll certainly get a good look in the spring.”10 Buckner, not lacking for confidence, responded by saying, “I think I can hit .300 in the majors. I know I’m a better hitter right now than some who have been playing there.”11 Some within the Dodgers organization were urging Alston to commit to playing Buckner. Scout Goldie Holt told club vice president Al Campanis, “Buckner has so much ability and is so far advanced that I would put him in left field and leave him there against all kinds of pitching.”12 Holt was not the only one who predicted big things for Buckner. When the Dodgers traveled to Pompano Beach to play the Washington Senators in a spring training match-up, the Dodgers’ batting practice turned into a hitting clinic of sorts as players and coaches gathered around Washington manager Ted Williams, who discussed hitting techniques. After watching Buckner take some swings in the batting cage, Williams remarked, “You don’t have to worry. You’re going to be an excellent hitter one of these days.”13 He predicted Buckner would eventually win a batting title.

Buckner received the Dearie Mulvey Memorial Award as the Dodgers’ outstanding rookie of the spring after batting .303 in 19 games with a club-leading five doubles and five stolen bases. He didn’t commit an error in the field or strike out at the plate. His performance earned him a place on the big-league roster, and he opened the regular season as the starting left fielder. He recorded his first major-league hit on April 8 against the Cincinnati Reds, but struggled to a .121 average in 14 games. In early May he was optioned along with Steve Garvey to Spokane. Buckner opted not to immediately report to Spokane in order to complete his semester of college courses at Southern California. He was given permission by the Dodgers to remain in Los Angeles to complete the courses and reported roughly three weeks later to Spokane. Dodgers general manager Al Campanis, who approved Buckner’s request, said he didn’t “understand what Billy was doing about his schooling when we were on the road. If he was making up the courses through correspondence, why can’t he continue to do so from Spokane? He certainly has our permission to return for tests.”14 Once Buckner arrived at Spokane, he wasted little time. He recorded seven hits in nine at-bats before suffering a broken jaw in a collision with teammates Davey Lopes and Bobby Valentine. He played two games before x-rays revealed the fracture. Recalling the injury, Spokane manager Tommy Lasorda said, “Buck broke his jaw and the front office told me to sit him out for five weeks. Buckner missed only one game and wound up hitting .335 and learned to spit and swear with his jaw wired shut.”15 He strung together a 12-game hitting streak in July, and wound up as one of seven Spokane batters to hit at or above .300. The club’s .299 team average established a modern Pacific Coast League record. Buckner, who played 65 games at first base and 57 in the outfield, was one of six Spokane players named to the PCL All-Star Team. He was recalled by the Dodgers in September and batted .257 in 14 games to raise his overall major-league season average to .191.

Buckner stuck with the Dodgers as an outfielder out of spring training in 1971. He liked playing for the Dodgers, confidently declaring, “I know I can play in the big leagues and hit .300, and I hope it’s with the Dodgers because this club has a good chance to win, and that means a lot of money. In fact, it means more than my entire season’s salary. This club gives you something to shoot for.”16 He hit his first big-league home run in the second game of the season and went on a tear in June and July. He hit his first career grand slam on July 27 in an 8-5 win over Pittsburgh, his second five-RBI game of the month. San Francisco Giants manager Charlie Fox observed of Buckner, “I think his position eventually will be first base, and I’d like to have him right now to fill in there when we needed him. He’s going to be quite a hitter.”17 Buckner and some of the other young Dodgers batters faded late in the season. He finished at .277 in 108 games as the Dodgers placed second in the National League West behind the Giants. He was selected as an outfielder on the Topps Rookie All-Star Team. Since the previous season, Buckner had been the subject of frequent trade rumors, as other teams coveted the Dodgers’ young talent. While speaking at a banquet in Southern California, Buckner said of the trade rumors, “The Dodgers may now have Frank Robinson and Tommy John, but they won’t have a chance at the pennant if they trade me.”18 He and the club expected big things in 1972.

Buckner caught fire at the plate in July 1972 to move into the top 10 among National League batting leaders (though lacking enough at-bats to qualify) while earning starting opportunities against righties and lefties. He hit in 13 of 16 games, going 25-for-57 with two home runs, three stolen bases, and 15 RBIs. In all, he played in 105 games, splitting time between first base and the outfield, while improving his batting average to .319. Many felt that Buckner was a good bet to replace the retiring Wes Parker at first base in 1973. After the season he enrolled for the fall semester at the University of Southern California as a junior in the School of Business Administration.

Buckner once again split time at first and in the outfield in 1973. He finished the season batting .275 with 12 stolen bases in 14 attempts, while scoring 68 runs. The Dodgers managed their fourth straight second-place finish in the division, this time 3½ games behind the Cincinnati Reds.

Before the 1974 season began, several Dodgers went Hollywood. Buckner, Tom Paciorek, and Tommy Lasorda agreed to shaves and haircuts for the opportunity to serve as extras in scenes filmed for The Godfather Part II in Santa Domingo, Dominican Republic, in January 1974. As Paciorek recalled it, “After we spent all day there getting fitted for uniforms and getting our hair cut, they called and told us that our parts had been canceled. Later, Tommy, Buck, and I were going deep-sea fishing. Buck wanted to get in the film and they were filming that night, so we went back. The scene they were filming is when Michael Corleone finds out it was Fredo. We are in that scene. We didn’t actually get our faces in the scene, but my right arm is!”19

Before the 1974 season began, several Dodgers went Hollywood. Buckner, Tom Paciorek, and Tommy Lasorda agreed to shaves and haircuts for the opportunity to serve as extras in scenes filmed for The Godfather Part II in Santa Domingo, Dominican Republic, in January 1974. As Paciorek recalled it, “After we spent all day there getting fitted for uniforms and getting our hair cut, they called and told us that our parts had been canceled. Later, Tommy, Buck, and I were going deep-sea fishing. Buck wanted to get in the film and they were filming that night, so we went back. The scene they were filming is when Michael Corleone finds out it was Fredo. We are in that scene. We didn’t actually get our faces in the scene, but my right arm is!”19

Buckner enjoyed his best season to date in 1974. He hit in 17 straight games before going hitless in the second game of a doubleheader on May 15 against Houston. He had four hits in his next game, against Atlanta. He also made play after play in the outfield, including several highlight-reel-quality catches, prompting The Sporting News to note, “Even more impressive than Buckner’s hitting has been his fielding. The left fielder has made five brilliant catches.”20 Buckner finished the regular season batting .314, and with his stellar defensive play received some modest consideration for National League MVP. Dodgers pitcher Don Sutton said, “And Buckner. Wow! If he doesn’t get some votes – I mean a lot of votes – it’s an injustice. He’s made so many unbelievable catches out in left field we’re starting to take him for granted.”21 Buckner finished 25th in the voting.

The Dodgers won 102 games and the division, and beat the Pittsburgh Pirates three games to one to advance to the 1974 World Series against the two-time defending World Series champion Oakland A’s. The clubs split the first two games, and Oakland took Game Three despite an eighth-inning home run by Buckner off ace Catfish Hunter. As motivation prior to the start of Game Four, A’s owner Charlie Finley called a team meeting and read a San Francisco Examiner article that quoted Buckner as suggesting the A’s were an inferior ballclub. The article quoted Buckner as saying, “I definitely think we have a better ballclub than they do. The A’s have only a couple of players who could play on our club. Reggie Jackson is outstanding. Sal Bando and Joe Rudi are good and they have a good pitching staff. Other than that … I think if we played them 162 times, we could beat them 100.”22 Oakland won Game Four by a score of 5-2. In the top of the eighth inning of the decisive Game Five, Buckner laced a hit to center, but was thrown out trying to stretch it all the way to third base, ending any threat to mount a late-inning scoring opportunity. He made no apologies for the play, noting, “It was something I did all year and I’ll do it again. I can’t stop taking chances because I got caught once.”23 Dodgers manager Walter Alston agreed, calling it “one of those plays. If you make it, it’s a great play. If you don’t, it’s a bad play. We let our players go all season. We want them to play aggressively. Bill just ran into two great throws, a perfect throw from the outfield and a perfect throw from the relay man.”24 The A’s, the club with only “a couple of players” who could play on the Dodgers, clinched their third straight World Series title with a 3-2 victory.

Buckner hoped to build upon his successful 1974 campaign the following season. But it was not meant to be. The 1975 season proved trying for Buckner, who suffered a severely sprained left ankle sliding into second base against the Giants on April 18. Forced to wear a cast, he did not return to the playing field until May 16, and he went hitless in eight of his first nine games back. His ankle never healed. Suffering from a pulled thigh muscle as well, he remained in the lineup, saying, “Every game is critical now, so I’ve got to keep playing. Between that and the bad ankle, I must be carrying three pounds of tape around every night. I can’t be as aggressive as I want to be. I can’t bunt. If I hit grounders on the infield I can’t beat ’em out. That’s probably 35 or 40 hits over the whole season.”25 Managing a meager .243 batting average in just 92 games, Buckner was finally shelved in late August and had ankle surgery on September 1.

With his season over, Buckner believed himself to be a trade option for the Dodgers, offering, “I definitely think I’m available. It all depends on what the Dodgers decide that they need. I’ve been hurt and I think the Dodger management is the best in baseball. But you have to remember that there’s no sentiment in baseball.”26 Nevertheless, he opened the 1976 season as the Dodgers’ starting left fielder and rebounded to play 154 games, bat .301 and set a new career high with 60 runs driven in. He sat out three games in late April/early May with a sprained left ankle, but returned on May 2 to beat out a pinch-bunt single to beat the St. Louis Cardinals. “I figured I could hold my breath four seconds,” Buckner said of the surprise bunt.27 He once again underwent surgery on his left ankle at the conclusion of the season.

On January 11, 1977, The Dodgers traded Buckner, shortstop Iván de Jesús, and minor-league pitcher Jeff Albert to the Chicago Cubs for outfielder Rick Monday and pitcher Mike Garman. Initially Buckner was furious and bitter, but eventually warmed to the idea. Of the trade, he said, “Sure, I’ll miss the Dodgers. And I’ll miss Tommy Lasorda. Lasorda raised me up. I even played for him when he was managing in the minors. I was looking forward to playing for him in his first year as the Dodger manager. At least I know this: The Cubs wanted me. The Dodgers didn’t.”28 The Cubs intended to make Buckner their everyday first baseman.

Buckner’s Cubs debut was placed on hold, as he began the season on the disabled list, still recovering from ankle surgery and a fractured left index finger suffered the first week of spring training. He delivered a pinch-hit single in his first game, on April 19, and proceeded to hit safely in eight of his first 10 games. He was relegated to pinch-hitting duties for most of May after re-injuring his left ankle while trying to go from first to third in a game on May 4. Buckner returned to the starting lineup on June 6, but struggled at the plate before catching fire in August. He exacted a sort of revenge on the Dodgers on August 19, recording four hits, including a pair of home runs, to go along with five RBIs in a 6-2 win in Chicago.

Years later Buckner fondly recalled, “I felt better than I had that game and my ankle didn’t seem to bother me at all. The Dodgers were going good – they had something like a 12-game lead in their division – and we were struggling. I seldom had as good a stretch in my career. Altogether I had eight hits, eight runs batted in and three homers in three games. I don’t think any other achievement in baseball has given me as much satisfaction. I’d shown the Dodgers I could still play.”29

Buckner’s August included one six-game stretch in which he went 14-for-28 with two home runs, two doubles, and seven RBIs. He was voted NL Player of the Week for the period ended August 21. He did so while playing hurt every day. Cubs manager Herman Franks lamented, “Lord knows where we’d be if we had him healthy all season. He’s probably playing at no more than 50 percent. I’d just like to have him at 90 percent next year.”30 The Cubs played .500 ball in 1977 and finished fourth in the NL East Division, 20 games behind the Philadelphia Phillies. As the season drew to a close, Buckner was considered among the leading candidates for the annual Hutch award, given to a player “who best exemplifies the character, fighting spirit, and competitive desire” of Fred Hutchinson, who died of cancer. He finished the 1977 season with a .284 average and a career-high 11 home runs.

Despite his initial misgivings about the trade, Buckner embraced the city of Chicago. His gritty hustle on the field made him a fan favorite. With the acquisition of free-agent slugger Dave Kingman, optimism ran high going into the 1978 season. Buckner, often hobbling on his bad left ankle, turned in a .323 average and 74 runs batted in. But the Cubs finished in third place, four games under .500. In the offseason, Buckner utilized ballet techniques in an effort to stay fit and improve his legs and ankle. He decided to stay the winter in Chicago. No one on the club made more personal appearances. General manager Bob Kennedy remarked of Buckner, “He’s the one guy we can count on to get out and represent us. He’s our Steady Eddie, just like he is at the plate.”31 In the winter, Buckner accepted the Player of the Year Award from Chicago’s baseball writers at their annual Diamond Dinner.

The following spring, Buckner was one of 17 players under consideration for the annual Roberto Clemente Award, given to the man who “best exemplifies baseball on and off the field.” He agreed to a contract extension through 1984 for an estimated $1.3 million. The deal was applauded by the fan base. Chicago baseball writer Dave Nightingale described Buckner’s place in the hearts and minds of Cubs fans by writing, “He created an image that was totally foreign to the Cubs last year by running out grounders to second base with his leg dragging behind him. He didn’t peel off to the dugout at the 45-foot mark.”32 The 1979 Cubs were a disappointment, despite a career year from Kingman and a Cy Young season from reliever Bruce Sutter. In one of the season’s strangest games, Buckner had four hits, including a grand slam, and seven RBIs in a 23-22 10-inning loss to the Phillies on May 17. He finished the season with a .284 average and 14 home runs. The club finished a disappointing fifth place with an 80-82 record.

Cubs manager Herman Franks announced his retirement at season’s end, but sparked controversy on his way out when an article by Bob Nightengale appeared in the Chicago Tribune headlined, “Franks Blasts Cubs ‘Whiners.’” Franks criticized several players including Buckner, of whom he is quoted as saying, “I thought he was the All-American boy. I thought he was the kind of guy who’d dive in the dirt to save ballgames for you. What I found out after being around him for a while is that he’s nuts. … He doesn’t care about the team. All he cares about is Bill Buckner.”33 Upon reading the comments, Buckner was furious. In an interview with the Tribune, he said, “Have you ever seen a rip job like that? He’d better come down here and give me an apology before the whole team. I’ve been busting my tail for three years. I’ve played when I shouldn’t be playing. The fans have appreciated me in the past. I don’t know how many millions read that paper and it’s really making me look like an idiot.”34 Franks ultimately refused to apologize for the comments, but stated that he wished they had not been printed.

Buckner married flight attendant Jody Schenck on Long Island on February 16, 1980. They planned to move to Chicago from a northwest suburb. Buckner found an old church that was being converted into condominiums and bought the tower apartment. As is the case every spring, the Cubs began the 1980 season hoping to compete. For his part, Buckner went to the plate 114 times before finally striking out against Joe Beckwith of the Dodgers on May 14. When the Cubs acquired slugging first baseman Cliff Johnson from the Cleveland Indians in June, Buckner volunteered to go the outfield to make room for Johnson’s bat in the lineup. Asked about the move, he responded simply, “I’d rather not, but if it will help the club, I’ll do it.”35 Despite a bad ankle, bad feet, and bad legs, a 10-game hitting streak that ended on September 14 saw him push to the lead in the batting race. He went 0-for-4 on the final day of the season, but finished ahead of the St. Louis Cardinals’ Keith Hernandez, .324 to .321, for the batting title. As the end of the season neared, articles started appearing suggesting that Buckner wanted out of Chicago. Commenting on the club’s season, he confessed, “I’ve never been this depressed ever in baseball.”36 After the season he asked general manager Bob Kennedy for a trade. “I feel maybe it’s time to make a move,” he said. “I’m in my prime, but it doesn’t seem like they’re going to put a winning club on the field. If I thought we had a chance to be competitive, I’d stay.”37 Buckner was once again honored as the Chicago Player of the Year by the Chicago chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America.

With four seasons remaining on his contract, Buckner threatened to sit out the 1981 season on his cattle ranch in Idaho if the Cubs did not renegotiate his $310,000-a-year contract. He was the frequent subject of trade rumors, and was nearly dealt to the Yankees for pitcher Dave Righetti in the spring. For season he batted .311, led the league with 35 doubles, made his first All-Star Team, and finished 10th in MVP voting. But Buckner’s dissatisfaction with losing and his desire to leave Chicago became a constant issue for the remainder of his time with the Cubs. Before the 1982 season, the Cubs renegotiated his contract and he responded by establishing new personal bests with 201 hits, 15 home runs, and 105 runs batted in. He again finished 10th in MVP voting. When offseason rumors swirled around the possibility of Steve Garvey becoming a Cub, Buckner was more than receptive if it improved the team. “I want to be on a winning club more than anyone. If that’s the way they feel they can improve the most, I’ll give it my best shot.” said Buckner, who even volunteered to go back to playing left field.38

Though he batted .280 with a league-leading 38 doubles in 1983, Buckner’s role on the club in 1984 was uncertain. He opened the season as the first baseman, with trade rumors swirling around him, but was quickly benched in favor of Leon Durham. Cubs fans gave Buckner a standing ovation during introductions at the home opener at Wrigley Field. Durham was booed. After the game Cubs manager Jim Frey praised Buckner, saying he “has handled this about as well as a player as good as he is can. I’m proud he hasn’t initiated any problems. … He’s had the chance, with the media around, to go the other way. It would be easy for him to say a lot of negative things. But the only thing he has said is that he wants to play, and I can’t fault him for that.”39 On May 25 Buckner was traded to the Boston Red Sox for pitcher Dennis Eckersley and outfielder Mike Brumley. Buckner was ecstatic, announcing, “It’s a new league and a new park. I’m excited about the deal. You never know how good you have it in baseball until you’re not playing. Trades are part of the game. I was treated very well in Chicago. I have no complaints. But now I’m in Boston, and I just want to get off to a good start and make a good impression.”40 He suited up and started at first base for the Red Sox on May 26 against the Kansas City Royals.

Buckner sparked his new club, batting .321 with nine runs batted in as the Red Sox won 12 of the first 15 games he started. He got his 2,000th hit against the Baltimore Orioles in June, as he quickly acclimated himself to his new surroundings with the Red Sox. Discussing Boston, Buckner declared, “I couldn’t have picked a better place to go. I love the city. I love the ballpark and I like everybody on the team. It’s something to motivate me to do as well as I can so I can play as long as I can.”41 The Red Sox finished the season in fourth place, as Buckner contributed a .278 average, 11 home runs, and 67 runs batted in in 114 games. At the conclusion of the season, he underwent surgery to remove bone fragments from his left elbow.

Boston dropped to fifth place in 1985 with an 81-81 record. Buckner batted .299 with a career-high 110 runs batted in. He finished the season strongly, getting 16 hits and three home runs while driving in 11 runs in his last six games. His 201 hits for the season broke Jimmie Foxx’s 49-year-old franchise record for hits in a season by a first baseman. Reflecting on his performance, Buckner regretted the club’s fortunes, noting, “Personally, it is a very satisfying season. But there is no substitute for winning, and we didn’t win. I thought we were going to do something when we left spring training, but it wasn’t to be. The injuries hurt, and we didn’t play well.”42 The Red Sox and their fans were disappointed, but the pieces were in place for a more successful campaign in 1986.

The 1986 Boston Red Sox finished the season fifth in the American League in runs scored. But the team’s real strength was its pitching staff. Starter Roger Clemens emerged to win 24 games and claim the title of the game’s best pitcher. The entire staff finished second in the league in strikeouts and tied for the third-highest saves total in the league. Buckner recognized the staff’s value and spoke highly of Clemens, saying, “I’ve never played behind a pitcher who I felt so confident behind, so sure that we would win.”43 In July Buckner announced his intention to address painful bone spurs in his left ankle with offseason surgery. Even in constant discomfort, he managed 18 home runs, a new season high, and his third and final 100-plus-RBI season. The Red Sox won the AL East by 5½ games over the Yankees. They beat the California Angels in dramatic fashion to advance to the World Series against the New York Mets. Buckner had batted a disappointing .214 against the Angels, but hobbled into the Series against the Mets confident in his team’s chances.

The Mets won the 1986 World Series. Game Six is now legendary, and widely regarded as one of the greatest games ever played. The Mets won the game in 10 innings, by a score of 6-5. Bill Buckner’s role in the loss is well-known. On the game’s final play, a groundball off the bat of Mets outfielder Mookie Wilson rolled between his legs at first base, allowing Ray Knight to score the winning run and push the series to a decisive Game Seven. The headline in the Boston Herald the next morning read, “Buckner Boots Big Grounder.” Boston went on to lose Game Seven, 8-5, failing to end the organization’s 68-year championship drought known by some as “The Curse of the Bambino.” For many Boston fans and observers, Buckner’s error was the reason the curse remained intact. For Buckner, it marked the beginning of near-constant criticism, heckling, and abuse. His name became synonymous with the derisive term “goat,” and the error was destined to be replayed on television ad nauseam. More than a decade later, Buckner remarked, “I’ll be seeing clips of this thing until the day I die. I accept that. On the other hand, I’ll never understand why.”44 Most experts acknowledged that the error was only one of several mistakes and blunders that contributed to the loss to the Mets. But for many there was little question the bulk of the blame was placed on Buckner’s shoulders. It would prove a heavy burden.

Buckner had offseason surgery on his feet and ankles, but faced a slow rehabilitation process. He started the 1987 season at first base, but after batting .273 with two home runs through 75 games, he was released. The decision, not made easily, prompted Red Sox manager John McNamara to say, “He has been one of the most competitive people I’ve ever been associated with. It wasn’t easy for him to get ready to play, but he had a tolerance for pain and did a great job for us. It was a difficult decision. There was a lot of sentiment involved.”45 For his part, Buckner confidently declared, “I think I can help somebody. I just hope I get the chance to prove it.”46 On July 28 he signed with the California Angels. He batted .306 in 194 plate appearances, and was the club’s top hitter after his signing.

Buckner was released by the Angels on May 9, 1988, while sporting a meager .209 batting average. Four days later he signed with the Kansas City Royals. He remained with the Royals through 1989, primarily serving as a pinch-hitter. He was granted free agency on November 13 and in February 1990 reached agreement to return to the Red Sox. But after batting just .186 in 48 plate appearances, he was released on June 5. Acknowledging that it was the end of the line, Buckner said, “I’m disappointed. I would have liked to finish the last year here. It’s the end of the line and I wanted to be on a winning team. It would have been nice, but…”47 He retired with a .289 career batting average, 2,715 hits, and 498 doubles.

In the summer of 1993, Bill and his wife moved their three children, daughters Brittany and Christen and a son, Bobby, to a ranch in Meridian, Idaho. Buckner’s wife, Jody, described one of the primary benefits of the location, pointing out that Meridian “isn’t a sports town. Nobody in this town would talk about Willie in a derogatory way.”48

Buckner invested in real estate in the Boise area, and worked briefly in the Toronto Blue Jays organization as a hitting instructor. In 1996 he was hired as hitting coach by the Chicago White Sox, replacing his own former hitting tutor, Walt Hriniak. He was fired in August 1997, despite the fact that the club was batting .271, good enough for eighth in the league. Other coaching stops included serving as manager for the Brockton Rox of the independent Can-Am Association in 2011, and as hitting coach for the Boise Hawks, the Chicago Cubs’ short-season affiliate, from 2012 until his announced retirement in March 2014. Stating his desire to spend more time with his family, Buckner said, “Just too much time away. My wife has put up with it for 30-something years. I know that Jody would want me to be home. It was just the right thing to do. I’ve been doing it a long time, and it’s been great. I will miss it. I enjoyed it. I enjoyed working with the kids. Some of them I worked with the last couple years are getting at-bats in spring training now. That’s fun to watch.”49 Buckner worked with several of the young players in the Cubs’ organization who contributed to the club’s appearance in the 2015 postseason.

On April 8, 2008, Bill Buckner returned to Fenway Park to throw out the first pitch at Boston’s home opener. The club was celebrating its 2007 World Series title, and Buckner received a four-minute standing ovation. After the game, an emotional Buckner reflected on the day’s events, saying “[It was] probably about as emotional as it could get. A lot of thoughts [were] going through my mind. I wish I didn’t have to walk all the way from left field, too many things. But just good thoughts, which is a nice thing. I really had to forgive, not the fans of Boston, per se, but in my heart, I had to forgive the media for what they put me and my family through. I’ve done that, and I’m over that and I’m just happy.”50 The Boston fans not only forgave Buckner, but accepted him back with open arms.

On September 17, 2015, President Barack Obama spoke to a friendly crowd of supporters in Boston, where he criticized congressional Republicans for failing to pass a budget and risking a government shutdown. Using sports analogies to make his point, he was quoted saying, “So a shutdown would be completely irresponsible. It’d be an unforced error. A fumble on the goal line. It’d be like a ground ball slippin’ through somebody’s legs.”51 The obvious reference to Bill Buckner and the 1986 World Series drew sharp boos and groans from the crowd. For Bostonians, Buckner was back to being family and that carries with it an allegiance that transcends everything, even politics.

Postscript

Buckner died at the age of 69 on May 27, 2019, after battling Lewy Body Dementia for some time.

This biography was originally published in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Sources

Photo credits: The Topps Company and Boston Red Sox

Notes

1 Paul Dickson. The New Dickson Baseball Dictionary (San Diego: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1989), 215.

2 The Sporting News, March 25, 1972: 29.

3 The Sporting News, August 27, 1977: 13.

4 The Sporting News, July 16, 1977: 15.

5 Vallejo Times-Herald, October 20, 1974.

6 Jim Kaplan, “He’s Off in a Zone of His Own,” Sports Illustrated, September 13, 1982.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 The Sporting News, October 4, 1969: 10.

10 The Sporting News, January 10, 1970: 51.

11 Ibid.

12 The Sporting News, February 28, 1970: 21.

13 The Sporting News, April 4, 1970: 14.

14 The Sporting News, May 23, 1970: 47.

15 Peter Gammons, “The Hub Hails Its Hobbling Hero,” Sports Illustrated, November 10, 1986.

16 The Sporting News, April 10, 1971: 28.

17 The Sporting News, July 31, 1971: 21.

18 The Sporting News, December 25, 1971: 28.

19 Colin Gunderson, Tommy Lasorda: My Way (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2015), 164.

20 The Sporting News, June 8, 1974: 7.

21 The Sporting News, October 12, 1974: 11.

22 The Sporting News, November 2, 1974: 10.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 The Sporting News, August 9, 1975: 25.

26 The Sporting News, August 30, 1975: 5.

27 The Sporting News, May 22, 1976: 16.

28 The Sporting News, February 5, 1977: 36.

29 Baseball Digest, April 1981.

30 The Sporting News, August 27, 1977: 13.

31 The Sporting News, December 23, 1978: 46.

32 Baseball Digest, August, 1979.

33 Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1979.

34 Chicago Tribune, September 26, 1979.

35 The Sporting News, July 26, 1980: 25.

36 The Sporting News, September 20, 1980: 14.

37 The Sporting News, November 29, 1980: 45.

38 The Sporting News, November 22, 1982: 42.

39 The Sporting News, April 30, 1984: 12.

40 The Sporting News, June 4, 1984: 19, 20.

41 The Sporting News, July 16, 1984: 27.

42 The Sporting News, November 18, 1985: 48.

43 The Sporting News, October 13, 1986: 16.

44 Wall Street Journal, July 24, 1998.

45 The Sporting News, August 3, 1987: 18.

46 Ibid.

47 The Sporting News, June 18, 1990: 15.

48 Wall Street Journal, July 24, 1998.

49 https://baseballthinkfactory.org/newsstand/discussion/bill_buckner_retires_from_baseball.

50 https://m.mlb.com/news/article/2504342/.

51 politico.com/story/2015/09/obama-boston-buckner-labor-baseball-red-sox-213383.

Full Name

William Joseph Buckner

Born

December 14, 1949 at Vallejo, CA (USA)

Died

May 27, 2019 at Boise, ID (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.