Bill Riggins

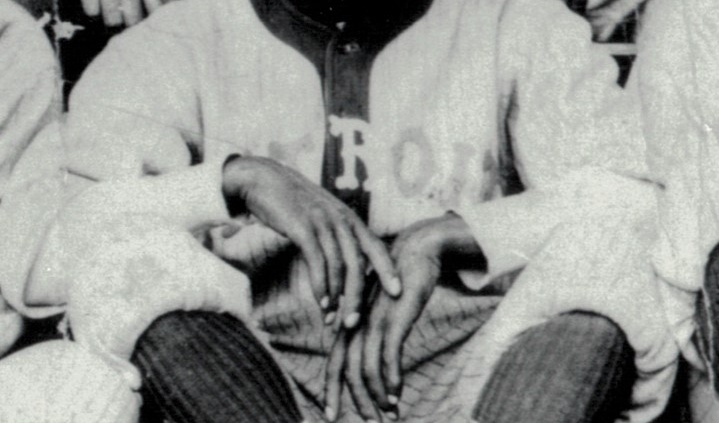

Arvell “Bill” Riggins, a shortstop-third baseman who played from 1920 to 1935, was an under-appreciated player whose professional career began at the same time as the first Negro National League.1 Riggins hit for a solid .292 average over the course of his career in Black baseball’s major leagues but has remained less well known than some of his peers because he toiled primarily for squads that were not of championship caliber. Despite his teams’ lack of success at reaching the playoffs, the infielder made a name for himself in the Midwest, where he played seven years with the Detroit Stars, before moving East and splitting the latter part of his career between three New York-area teams.

Arvell “Bill” Riggins, a shortstop-third baseman who played from 1920 to 1935, was an under-appreciated player whose professional career began at the same time as the first Negro National League.1 Riggins hit for a solid .292 average over the course of his career in Black baseball’s major leagues but has remained less well known than some of his peers because he toiled primarily for squads that were not of championship caliber. Despite his teams’ lack of success at reaching the playoffs, the infielder made a name for himself in the Midwest, where he played seven years with the Detroit Stars, before moving East and splitting the latter part of his career between three New York-area teams.

Arvell Riggins was born in the area around the future town of Colp, Illinois, on February 7, 1900, to Daniel and Ida (Miller) Riggins. Colp, founded in 1901, was named after farmer-turned-mine-owner John Colp and is in the formerly coal-rich area of Williamson County in Southern Illinois. Colp sold his mine to the Madison Coal Corporation in 1906 and the new owners named the area around the mine No. 9.2 Although Colp and No. 9 existed side by side, distinct boundaries were drawn. According to Ron Kirby, a former Colp resident who worked to preserve the area’s history, “In defining areas, we spoke of the village of Colp, as the ‘white camp,’ which were streets outside of the incorporated town where whites only lived; the ‘black camp,’ signifying No. 9; and the ‘yellow camp,’ which was geographically on the highway to Herrin and identified by the yellow company houses.”3

Riggins may have lived in nearby Dewmaine, a village several miles to the south that had been founded in 1899 and is now a ghost town, as there is some question regarding which settlement was his true birthplace.4 The name Dewmaine was inspired by two names from the Spanish-American War in 1898: the USS Maine, the ship that exploded and accelerated the onset of the conflict, and Commodore George Dewey, the American hero of the Battle of Manila Bay.

In addition to its colorful name, Dewmaine had an equally interesting origin. Samuel T. Brush, general manager of the St. Louis and Big Muddy Coal Company in nearby Carterville, brought the first Black miners to the area to break a strike by White union miners in May 1898, just three weeks after the Battle of Manila Bay. The union laborers returned to work in July but went on strike again in May 1899. Brush brought additional Black workers to Dewmaine, which resulted in violence. One woman died when the new workers’ train was fired upon, and another five Black men were killed at the Carterville train station.5 Brush, like John Colp, sold out to the Madison Coal Company in 1906, and his mine in Dewmaine became known as the No. 8.6

It is possible that Arvell’s father, Daniel Riggins, had been among the first group of Black miners to arrive in the area in 1898. Daniel and Ida Miller were wed in Williamson County on May 4, 1899, and the couple embarked upon married life and started a family amid the violent events precipitated by the early union unrest among the area’s coal mines.7

When Arvell Riggins registered for the World War I draft in September 1918, he listed the Madison Coal Company as his employer. In 1920, baseball became his escape route from a life in the mines, an unhealthy occupation that would not have been available to him much longer in any case, as the No. 8 mine ceased operation in 1923 and the No. 9 closed in 1930.8

At the time of the 1920 census, Riggins was already married to Jeanette “Jennie” Jefferson, and the couple was living with Jennie’s family in Colp. The exact date of their marriage is unknown, though the year 1919 is most likely. Their first child – Arvell Jr. – was born on July 21, 1920, in Colp.9 Young “Baby” Riggins’s photograph was featured in the Chicago Defender’s June 18, 1921, edition to accompany an article about the Detroit Stars’ June 12 doubleheader sweep of the Columbus Buckeyes. Jennie and Arvell Jr. had attended the games at Detroit’s Mack Park that day and the Defender claimed that “[t]he youngster took good pains to applaud his daddy when he singled” in the first game.10 The couple eventually welcomed two more sons into the family, William (b. 1922) and Lonnie (1924).

Riggins had embarked upon his professional baseball career in March 1920, just four months before his first son’s birth. It is unknown whether Riggins honed his skills on a school team, company team, or simply on the sandlots, but Rube Foster discovered him and assigned him to his Chicago American Giants squad of the new Negro National League to start the 1920 season.11 The 5-foot-8, 160-pound Riggins, a switch-hitter who threw right-handed, played in only three league games for Chicago before being reassigned to the Detroit Stars. He became Detroit’s starting shortstop and batted .275 in 59 games for owner Tenny Blount’s team, which finished in second place, eight games behind Chicago. Riggins’s performance during the regular season earned him the honor of joining the St. Louis Giants in a postseason series against teams of White major-league all-stars. He went 1-for-8 at the plate in two games played.

In December 1920 Riggins and outfielder Judy Gans were officially traded to the Detroit Stars in exchange for outfielder Jimmie Lyons.12 Thus, Riggins returned as Detroit’s shortstop in 1921 and appeared in 80 of the Stars’ 85 games against fellow Negro major-league teams. His hitting improved significantly as he raised his batting average 30 points to .305 and posted a .351 on-base percentage. Detroit finished the season with a 38-46-1 record that included a 30-33-1 ledger in NNL play, which put them in fifth place, 12½ games behind the champion Chicago American Giants.

If there was a knock against Riggins at this point in his career, it involved his fielding. He committed a whopping 48 errors in 75 games at shortstop, and his .883 fielding percentage was below the league average of .907. Events in a 3-2 loss to Hilldale at Razzberry Park in Camden, New Jersey, on September 7 were typical of Riggins’s misadventures in the field. Detroit led, 2-1, entering the ninth inning, but Riggins “paved the way for the Hilldale triumph by permitting Connie] Rector’s weak grounder to go through his legs after Otto] Briggs and Phil] Cockrell had been retired.” 13 Although Stars reliever Bill Holland issued two bases-loaded walks that resulted in Hilldale’s game-tying and winning tallies, Riggins’s error had made the tough loss possible.

Nonetheless, Riggins was one of the NNL’s noteworthy performers as was evidenced by the fact that he again appeared in the postseason, albeit in only a single game. This time, he played for the New York Lincoln Giants against the Bears, a team of White semipros led by former New York Giants pitcher Jeff Tesreau, who stymied Riggins into a 0-for-4 appearance with the bat. In the field, Riggins registered three putouts and three assists, but as was often the case, he also made an error.

In 1922 Riggins appeared in 81 games at shortstop for Detroit. His defense improved dramatically as he cut down his number of errors to 33, and his .922 fielding percentage was above the league average of .915. As fate would have it, however, his offense declined accordingly. Riggins hit only .247 for the season, 58 points less than in the previous season. In Detroit’s first season under new manager Bruce Petway (Pete Hill had skippered the team from 1919 to 1921) the Stars improved to a 50-34-1 record. The team was 42-31-1 in NNL play, which was still only good enough for fourth place, but it had closed the gap considerably; the Stars finished only 2½ games behind first-place Chicago.

Riggins once again played in the postseason as he joined the St. Louis Stars for a three-game series against the American League’s Detroit Tigers, managed by Bobby Veach. St. Louis won two games against the Tigers, who were without the services of Ty Cobb and Harry Heilmann. Riggins started all three contests at shortstop but had just one hit in nine at-bats and made two errors.

In 1923 Riggins put his offense and defense together and had his all-around breakout season for Detroit. He appeared in 71 games at shortstop during the NNL season and fielded his position at a .923 clip. (The league average was .918.) Although he made 36 errors, his fielding percentage now showed that number to be an indicator of his great range – rather than a shaky glove – as increased chances meant the increased possibility of errors. At the plate, Riggins batted .302 (80-for-265) and had a .379 on-base percentage; he scored 59 runs and drove in 43. The Stars finished the NNL season with a 39-27 record (41-30 overall) but were relegated to a third-place finish behind the league’s two powerhouses, the first-place Kansas City Monarchs and the Chicago American Giants.

Riggins remained a member of the Stars as Detroit played a three-game series against the American League’s St. Louis Browns in October. The Stars once again captured two of three games against a team of White major-leaguers, taking the first two games by identical 7-6 scores before losing the third game, 11-8. Riggins’ postseason struggles continued as he managed only a 1-for-12 batting line (.083) in the three games.14

Riggins, who had blossomed into a star, continued to ply his trade at shortstop for Detroit for three more years, from 1924 through 1926. He posted batting averages of .305, .267, and .300 during those seasons, and his fielding remained steady. Although Riggins’s batting average was subpar by his standards in 1925, he was still an offensive force and stole 26 bases, which placed him second in the league behind Cool Papa Bell, who stole 30 bags for St. Louis.

In both 1925 and 1926, the Stars played a 100-game NNL schedule, an unusually high number of league games for a Negro League squad, and Riggins played 94 and 91 games respectively. Although Detroit continued to be an above-average team, the Stars finished in third place in the NNL in 1924 with a 35-28-1 mark and then placed fourth in each of the next two seasons with records of 56-44 (1925) and 52-47-1 (1926).

Besides appearing in 91 games as shortstop of the Detroit Stars in 1926, Riggins also assumed the managerial reins from Petway and guided the team to a 44-34-1 record before being replaced by Candy Jim Taylor, who had skippered the Cleveland Elites for most of the season. The Stars had fared better under Riggins: Taylor led the team to an 8-13 ledger. Detroit finished a distant fourth, 16½ games behind the Kansas City Monarchs.

On March 8, 1927, in a surprising move, Detroit traded the veteran Riggins to the NNL’s newest team, the Cleveland Hornets, for first baseman Stack Martin and 22-year-old shortstop Halley Harding.15 Prior to a game against the Black Barons in early May, the Birmingham News raved that Riggins was “rated as one of the greatest negro shortstops in the country. He is a great fielder, bats in clean-up position and is fast on the bases.”16

The Cleveland team did not lack for hitting, with Riggins batting a career-high .341, left fielder Tack Summers hitting .355, right fielder Ernest Duff coming in at .318, and first baseman Edgar Wesley knocking the cover off the ball at a .424 clip. The pitching staff, however, was another story. The leading winners on the staff, Square Moore and Slim Branham, had a mere two victories apiece. Moore, Branham, and Howard Ross all had ERAs north of 6.00, while Frank Stephens barely missed joining the three with his 5.93 mark. However, Percy Miller outdid them all with a 9.33 ERA over 45⅓ innings pitched, though he somehow managed to escape with a 1-2 record. Oddly, Nelson Dean, who led the staff with 65⅓ innings pitched and had a 3.44 ERA (119 ERA+) was saddled with the worst record at 1-9. In the end, the Hornets fared as well as most expansion franchises do, especially with such wretched pitching, and finished the season with a 13-36 record (14-38 overall) that placed them seventh in the NNL, ahead of only the Memphis Red Sox, who finished at 25-69-3.

By August, Riggins had escaped the purgatory called Cleveland and was playing for owner Cumberland Posey’s independent Homestead Grays in Pittsburgh. He manned third base for a mere six games but continued to swing a hot bat as he hit .318 (7-for-22) in his limited appearances. Riggins moved back to his familiar position of shortstop for a series against a team of White major leaguers that was managed by Earle Mack and featured Heilmann and fellow future Hall of Famer Heinie Manush. The Grays won two of six games from the major leaguers while Riggins played in only two of the contests and went 2-for-7.

The 1928 season found Riggins with the New York Lincoln Giants – the team for which he had played a single game against a White semipro aggregation seven years earlier – as the team’s starting third baseman. In announcing Riggins’s acquisition, the Chicago Defender extolled him as “one of the best hot corner guardians in the business.”17 The New York Lincoln Giants were members of the Eastern Colored League in 1928 and were managed by future Hall of Fame shortstop John Henry “Pop” Lloyd. Riggins appeared in 33 games, batted .270, and fielded his position at a .949 clip (the league average was .907), making only five errors. Although the Lincoln Giants’ overall .533 winning percentage (21-17-2) was the best of the ECL’s five teams, the team’s 9-7-1 record and .563 winning percentage in league games put them in third place behind the first-place Atlantic City Bacharach Giants and second-place Baltimore Black Sox.

Lloyd was still in the manager’s seat in 1929 although, after the demise of the ECL, the Lincoln Giants were now a member team of the American Negro League. Riggins again manned the hot corner, though he occasionally played second base, and posted a career-high .344 batting average with a .444 on-base percentage in 66 games played. The Lincoln Giants had a fine season, posting a 40-26-2 league record (45-28-2 overall), but finished in second place, eight games behind the Baltimore Black Sox.

In 1930 Riggins returned for one final season with the Lincoln Giants squad that was now an independent club. He continued to flourish under Lloyd’s tutelage and batted .343 for the season, only one point lower than the previous year, as the team’s starting third baseman. The powerful Lincoln Giants finished with a 41-14-1 record. Although there was no league in the East that year, only the Homestead Grays finished with a better mark of 45-15-1 among the top independent clubs.

Although Riggins found steady employment with the Lincoln Giants from 1928 to 1930, his personal affairs were on shaky ground. Jennie and Arvell Jr. continued to live in the Detroit area while young William and Lonnie resided with their maternal grandparents, William and Lizzie Jefferson, back in Colp. In the meantime, Riggins abandoned the family that he had started with Jennie and apparently married a woman named Marion Carter in New York in 1929.18

According to the 1930 US Census, Riggins (whose first name was misspelled as “Arnell”) and Marion were residing at the family home of his new brother-in-law, John L. Carter, in Manhattan. Riggins listed his occupation as manager of a baseball club, even though Lloyd was the skipper of the Lincoln Giants at that time. He also gave his age at the time of his first marriage as 29, which indicates that he claimed his betrothal to Carter was his first marriage, and he claimed that he had been born in Missouri, not Illinois. The misinformation Riggins provided for the census was due to the fact that he was guilty of bigamy when he married Marion Carter and clearly was trying to conceal his first marriage from either his new in-laws, the authorities, or both.

The fate of Riggins’s second marriage is unknown, since no record has been found to indicate whether the couple divorced or that Marion died at a young age. The only certainty is that Marion was gone from Riggins’s life by the time he registered for the World War II draft in 1942, and he was living in Manhattan with another woman who may or may not have been his third wife.

Amid Riggins’s personal intrigue, the Lincoln Giants folded and were replaced in New York City by the Harlem Stars. Riggins was a member of the team but, for the most part, the Stars were such in name only. In mid-July, the New York Age reported:

“The experiment of having Negro teams play at the big-league baseball parks (the Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds) when the home team is away, has not met with the success its promoters had hoped for and will be abandoned before the present season is out. …

“Bill Robinson’s Harlem Stars was the team used in this experiment, and it is problematic whether they will complete the season. At any rate, the owner of the Lincoln Giants, James J. Keenan, plans to return to the semi-pro baseball field with another colored team for the Catholic Protectory Oval next season, and hopes to reclaim many of his old players, now with the Harlem Stars.”19

The Age identified three problems that had contributed to low attendance, and which presaged the demise of the club: Manager Pop Lloyd “was only able to get together [a] mediocre team on so short notice,” the price of admission was too high, and the publicity that past Black teams, like the Lincoln Giants, had “received in former years in the daily press [had] not been given.”20

As the Stars attempted to complete the 1931 season, the squad became financially strapped even more by events surrounding an August 16 doubleheader against Hilldale that was held at Yankee Stadium to benefit the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. According to the Age, both the New York Amsterdam News, whose “Sports Dean” Romeo L. Dougherty promoted the event, and the Brotherhood failed to pay the Stars or the umpires, although the Hilldale team was paid its share of money from the gate receipts and the Brotherhood was alleged to have received over $400 as well. The Age asserted that “benefit performances are becoming a racket in Harlem.”21 Dougherty had already addressed the fiasco three days earlier in his weekly column. Although he claimed, “I make no charge in the matter against anyone,” he then assigned blame to the co-promoters of the event when he asserted, “I have carefully studied the situation and found that too many cooks usually spoil the soup and that is what happened on [this] occasion.”22 In the end, while the Age’s accusations may have been extreme, they were not entirely unwarranted, and the doubleheader fiasco contributed to the financial instability of the Harlem Stars franchise.

The Stars managed to play a mere 18 games against other prominent Black teams in the East, and had a 6-12 record. Riggins started all 18 games, including 14 at second base and four at shortstop. His batting average dropped precipitously from the .344 and .343 marks of the previous two seasons to .239 as he managed only 16 hits and drew seven walks in the 18 games. Riggins’s days as a major contributor to top-caliber Black ballclubs were at an end, though he continued to play occasionally for the New York Black Yankees, the team that rose out of the ashes of the Harlem Stars in 1932.

In 1932 Riggins appeared in only seven games against major-league-caliber competition – six at third base and one as a pinch-hitter – for the independent Black Yankees. One of the games was a highlight of the Black Yankees’ season, on August 29 at Pittsburgh’s Greenlee Field. It was rare for a Negro League team to have its own ballpark, and Gus Greenlee and his Crawfords team had just held a grand dedication and played an exhibition game on their new grounds. The New Yorkers were the first Black major-league team to face the Crawfords, and the two teams dueled in splendid style as Satchel Paige and the Black Yankees’ Jesse Hubbard kept zeroes on the scoreboard until the top of the ninth inning. Riggins hit a one-out single in the final frame but was not to be the hero on this day as he was forced at second on Ted Page’s fielder’s choice. Page stole second, advanced to third on catcher Bill Perkins’s wild throw, and then scored the game’s only run when Clint Thomas singled.23 For the season, Riggins batted .278 (5-for-18) but drew more walks (6) than he had hits (5) in his limited time with the squad, which finished with a 17-14-1 record against its fellow independent Black teams.

After a two-year hiatus, Riggins returned to the Black Yankees for five games during the 1935 season. His name still carried enough clout that he was named as one of “the well-known colored stars that [would] appear” in a June 23 game against the semipro Bay Parkways at Erasmus Field.24 In five games against fellow Black professional teams, Riggins batted .231 before calling an end to his career as a ballplayer.

Over the course of his 14 years in the Negro Leagues, Riggins had a .292 career batting average and a .359 on-base percentage. His career 96 OPS+ denotes him as a slightly below-average batter, although in some of his better seasons he certainly had been among the top hitters in his league. In his Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James summed up Riggins as a “good switch hitter and a good shortstop, but a heavy drinker.”25 Although James used the designation “good” rather than “great,” Riggins was nonetheless a player of note in the early days of the Negro major leagues and, as such, his services were in demand elsewhere as well.

Riggins, like many ballplayers of his era, also played several seasons of winter-league ball. Early in his career he ventured west to participate in the California Winter League, which was the only integrated baseball league at that time. The 1922-23 season marked Riggins’s first stint in the Golden State, during which he played for the St. Louis All-Stars. He returned for the next two seasons and continued to play for the St. Louis teams (Stars in 1923-24 and Giants in 1924-25). After playing elsewhere for a few winters, Riggins joined the Nashville Elite Giants for one final winter in California, in 1930-31. In four seasons out West, Riggins batted .321 (87-for-271) in 72 games.26 It is likely that Riggins played in far more than those 72 games, however, as the California Winter League did not receive widespread press coverage during the early 1920s.

Riggins spent additional winters plying his trade in the Cuban Winter League, which was renowned for its ardent fans and stiff competition. In three seasons on the island, he played for Habana (1924-25), Almendares (1928-29), and Santa Clara (1929-30). Riggins batted .301 (80-for-266) and led the league with nine triples in the 1928-29 season.27 As was the case with the Negro League squads on which he played, Riggins never won a championship; each of his Cuban teams finished in second place.28

Riggins remained in New York after his playing days ended, but little is known about his post-baseball years. He registered for the World War II draft in February 1942, at which time he was employed as a longshoreman and listed Iver Mae Moore (the 48-year-old widow of a man named John Moore) as his contact person.

Riggins died on March 8, 1943, in the home he shared with Moore at 53 West 135th Street in Manhattan. He was 43 years old and died of multiple heart-related ailments, including hypertension, coronary thrombosis, and chronic myocarditis. His death certificate listed Moore, who provided all personal information for the document, as his wife. A close inspection of her signature on the document, however, shows that she began to sign her last name with the letter “M” but then wrote “Riggins” over it, casting doubt on whether the couple was married. Moore had Riggins buried in Beverly Hills Cemetery in Putnam Valley, New York, northeast of New York City. In addition to Moore, Riggins was survived by his mother, Ida; his first wife, Jennie; and at least two of their sons, Arvell (Orville) Jr. and William.

Ida Reed, his mother, had remarried after her divorce from Arvell’s father, Dan, and died in Chicago in 1947. (Dan had also remarried and had died on March 31, 1942, just one year earlier than his only son.) Jennie Riggins, on the other hand, never remarried and died in Detroit in 1981. Arvell Jr. served in the US Army during World War II and lived to the age of 90; he died in Detroit on November 30, 2010. William Riggins inherited his father’s athleticism, and he and his cousin, James Miller (from Ida’s side of the family), helped to lead Colp’s Herrin Township High School basketball team to the 1941 championship of the Southern Illinois Conference of Colored High Schools.29 William married a woman named Dorothy Mitchell in 1947 and settled in the Detroit area as well. No information about the life of Arvell and Jennie’s third son, Lonnie, is currently known. Also unknown is the fate of Riggins’s second wife, Marion Carter, and there is no record that she and Arvell ever had any children.

Although Riggins had a checkered personal life, he had gained a degree of fame as a baseball player in the early years of the first Negro National League. In July 2013 a committee from Colp announced plans to erect a plaque in Riggins’s honor on Dewmaine School Road.30 The idea came to fruition, and Riggins shares the “Hometown Heroes” plaque with fellow Colp native Jimmy Springs, who was inducted into the Vocal Groups Hall of Fame in 2007.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is extended to SABR member Dr. Frank Houdek, emeritus professor of law at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, for the research material he obtained from the Ronald W. Kirby Special Collection at SIU’s Morris Library and for traveling to the Colp-No. 9-Dewmaine area to take photos of the plaque that is dedicated, in part, to Arvell Riggins.

Negro League researcher Gary Ashwill has two posts about Riggins on his Agate Type website – “Who was Orville Riggins (May 23, 2007) and “‘Baby’ Riggins and his dad” (February 8, 2011) – that provided the foundation and direction for further research into events in Riggins’s life.

Sources

Ancestry.com was consulted for US Census information and military draft registration records, as well as birth, marriage, and death records.

Except where otherwise indicated, all player statistics and team records were taken from Seamheads.com.

Notes

1 Riggins usually signed his name as Arvell, but several sources spell it Orville. Additionally, Riggins sometimes used the name William or the shortened version, Bill. Riggins’ first father-in-law (Jennie’s father) was named William and Riggins gave his second-born son that name, but no evidence has come to light to explain why he also used the name for himself at times: However, in the latter part of his career, he became well-known in newspaper articles as Bill Riggins.

2 Mary Beth Roderick, “Colp & No. 9: A Few Miles and a Different Future,” Carbondale (Illinois) Southern Illinoisan, November 20, 2011: 9A-10A.

3 Roderick, “Colp & No. 9.”

4 Arvell Riggins listed Colp as his birthplace on his World War I draft registration card in 1918 but gave Dewmaine as his birthplace on his World War II draft card in 1942.

5 “Dewmaine History,” Williamson County Illinois Historical Society, https://www.wcihs.org/history/dewmaine-history/, accessed September 25, 2021.

6 Mary Beth Roderick, “Ghost Town: The Rise and Fall of Dewmaine,” Southern Illinoisan, November 20, 2011: 4A (article begins on 1A).

7 Daniel Riggins was born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1870. Most of the Black miners brought to Williamson County were from Tennessee, but Riggins obviously could have made his way from Georgia to Illinois via Tennessee. Ida Miller was born in Kentucky, but her family moved to Tennessee and later settled in Colp. It is unknown whether Riggins and Miller knew each other in Tennessee already or met for the first time in Williamson County.

8 Roderick, “Colp & No. 9”; Roderick, “Ghost Town.”

9 As was the case with his father, Arvell Jr.’s name had variant spellings. He often signed his name as Arvill (with an “i” rather than an “e”) and later used Orville. His official World War II Army enlistment records have the name Orvill (without the “e”).

10 “Baby Riggins Sees Detroit Cop 2 Games/Watches Father Perform as Shortstop and Applauds When ‘Dad’ Singles,” Chicago Defender, June 18, 1921: 11.

11 “’Rube’ Assigns Players to Giants,” Chicago Defender, March 20, 1920: 9. This article gives Riggins’s first name as Orville.

12 “Jimmy [sic] Lyons Comes to American Giants,” Chicago Defender, December 11, 1920: 6.

13 Frank H. Ryan, “Hilldale Wins in Ninth: Pinch Pitcher Forces Home Tying and Winning Runs,” Camden (New Jersey) Courier Post, September 8, 1921: 19.

14 “Browns Lose Again in Ninth,” Detroit Free Press, October 9, 1923: 24; “Browns Again Fall to Stars,” Detroit Free Press, October 10, 1923: 15; “Browns Check Stars in Final,” Detroit Free Press, October 11, 1923: 19.

15 “Cleveland Gets Riggins; Detroit Martin, Harding,” Chicago Defender, March 12, 1927: 8.

16 “Cleveland to Battle Black Barons Monday,” Birmingham News, May 1, 1927: 20.

17 “Riggins Now with Lincoln Giants Club,” Chicago Defender, March 31, 1928: 9.

18 Gwendolyn Young, Arvell (Orville) Riggins Jr.’s daughter, wrote two letters to Ronald W. Kirby (who was researching the history of his native town of Colp) that bear out the fact that Arvell Riggins Sr. abandoned his family. In a letter dated November 18, 2015, Young wrote, “[…] apparently Orville (Arvell) Sr. deserted the family by 1930 once he started playing ball in New York.” In a second, undated letter, she wrote, “My dad loved baseball, but he didn’t have much respect for Orville Sr. because he deserted the family and was a ‘dead beat’ [sic] dad.” (Both letters are contained in the Ronald W. Kirby Special Collection at Southern Illinois University’s Morris Library).

19 William E. Clark, “Playing of Negro Baseball Teams in Big League Parks Has Not Met with Success and Will Be Ended,” New York Age, July 18, 1931: 6.

20 Clark.

21 “Benefit Rackets,” New York Age, August 22, 1931: 6. See also, “But 3,000 Attend Benefit Games at Yankee Stadium,” New York Age, August 22, 1931: 6.

22 Romeo L. Dougherty, “In the Sports Whirl: When Is a Benefit Not a Benefit?” New York Amsterdam News, August 19, 1931: 12.

23 “Hubbard Pitches Three Hit Game to Beat Paige, 1-0,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 7, 1932: 15.

24 “Black Yanks Meet ‘Parks’: Stage Set for Great Clash Between Rival Nines on Sunday,” New York Amsterdam News, June 22, 1935: 16.

25 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract: The Classic – Completely Revised (New York: Free Press, 2001), 187.

26 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc, 2002), 260.

27 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 358. This book erroneously lists Riggins as playing with Almendares during the 1924-25 season; Figueredo’s second volume about Cuban baseball (see Note 28) gives the correct team as Habana.

28 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 158, 178, 182.

29 “Herrin Township at Colp ‘Tigers,’” http://www.illinoishsglorydays.com/id567.html, accessed October 17, 2021.

30 Bucky Dent, “Colp Negro League Star to Get Honor,” Southern Illinoisan, July 8, 2013: 1.

Full Name

Arvell Riggins

Born

February 7, 1900 at Colp, IL (USA)

Died

March 8, 1943 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.