Buck O’Neil

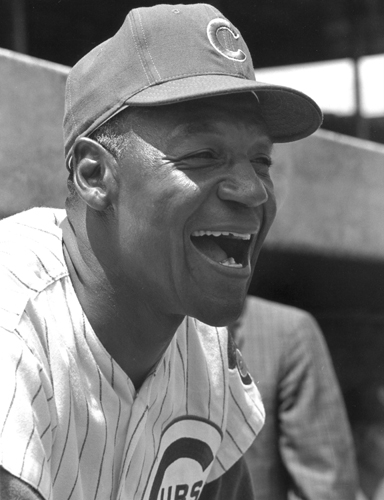

To tell the story of Buck O’Neil, one needs only to retell the stories by Buck O’Neil. He told stories of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and other Negro League greats forgotten to history because of the color of their skin. He told them with a twinkle in his eye, a smile from ear to ear, and a laugh that conveyed his passion to pass his stories on to the next generation. “Sometimes I think the Lord has kept me on this earth as long as He has so I can bear witness to the Negro Leagues,” he said.1 While he became the storyteller of the Negro Leagues, Buck O’Neil himself is an amazing story.

To tell the story of Buck O’Neil, one needs only to retell the stories by Buck O’Neil. He told stories of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and other Negro League greats forgotten to history because of the color of their skin. He told them with a twinkle in his eye, a smile from ear to ear, and a laugh that conveyed his passion to pass his stories on to the next generation. “Sometimes I think the Lord has kept me on this earth as long as He has so I can bear witness to the Negro Leagues,” he said.1 While he became the storyteller of the Negro Leagues, Buck O’Neil himself is an amazing story.

The grandson of a slave, O’Neil couldn’t attend high school in the segregated South, but the 12-year-old decided there had to be more to life than working in the celery fields. There was much more available to him but he had to go out and find it, his father told him. He would face many obstacles, including the Jim Crow South. Yet despite the ways he was treated as a person of color, he loved both the National Pastime and his country, serving the latter in World War II. He lived long enough to see dramatic changes in baseball and American society, although they came too late for Buck the ballplayer. It was utterly unfair that, had he been born later, he might have been a major leaguer. Yet when asked if he had regrets in missing such opportunities, his answer was definitive. “Waste no tears for me,” he said. “I didn’t come along too early—I was right on time.”2

Buck O’Neil told his stories for decades but few people heard them until the power of television brought him celebrity status in his 80s. A new generation that never knew what he experienced now saw the sparkling, silver-haired O’Neil describe the players who paved the way for a better country and better game. Seeking to preserve the memory of the Negro Leagues for all time, he helped establish a museum so those stories would never disappear from history again. O’Neil, in the words of Jules Tygiel, “reigned as a symbol of baseball’s past and the game’s greatest good-will ambassador.”3

John Jordan O’Neil Jr. was born on November 13, 1911, in Carrabelle, a fishing village on the Florida panhandle. The O’Neil family descended from the Mandingo tribe of West Africa. Buck’s grandfather, Julius O’Neil, was born on the banks of the Niger River and brought to America as a boy on a slave ship. Julius worked the cotton fields in the Carolinas for an owner with the surname of O’Neil, which Julius adopted as his own, a common practice. Buck remembered Julius, in his late 90s, sitting him down on his knee to tell him of the days on the plantation. When Julius was freed he moved to southern Georgia where Buck’s father, John Jordan O’Neil Sr. was born. John Sr. met Luella, also a descendent of slaves, and the two were married. John Sr. worked in a sawmill which often took him away from home to cut timber. Later he was a foreman in the celery fields. Luella took the main responsibility to raise the children, Buck with his older sister Fanny and younger brother Warren.4

On the weekends, John Sr. brought Buck along when he played on a local baseball team in Springdale. The team would survive by passing a hat for donations. In 1920 the O’Neil family moved to Sarasota. Luella was a cook for the Ringlings, the famous circus family, and later she opened a family restaurant. Sarasota was also the spring training home of the New York Giants. The Philadelphia Athletics and New York Yankees were also just a short distance away. Young O’Neil met legends such as Babe Ruth, Dizzy and Daffy Dean, and Lefty Grove.

Over the winter months, Buck’s uncle, who worked on the railroad, would travel to Florida and take Buck and his dad to West Palm Beach to see Rube Foster, the Chicago American Giants and Indianapolis ABCs of the Negro Leagues. Many of the players worked as porters at the Royal Poinciana Hotel, and played ball on their off days. 5 O’Neil had never seen baseball like this. “It’s fast, it’s quick,” he said. “You know how the dull moments in baseball can be. In this type of baseball, never a dull moment.”6 In his youth O’Neil was known as Jay, J.J. or Foots, due to his size-11 shoe when he was just 12. That year—1924–he was recruited by the Sarasota Tigers semipro team, where he played first base for two seasons.

“When I was twelve years old, I worked in the celery fields,” O’Neil recalled. “I would put the boxes out so they could pack the celery in the boxes to ship it. I was sitting behind the boxes one day in the fall of the year, and it was hot in Florida, and I was sweating and itching in that muck. My father was the foreman on this job and he was on [one] side of the boxes, and I was on the other side. And I said, ‘Damn. There’s got to be something better than this.’ So, when we got off the truck that night my daddy said, ‘I heard what you said behind the boxes.’ I thought he was going to reprimand me for saying ‘damn.’ But he said, ‘I heard what you said about there being something better than this. There is something better, but you can’t get it here, you’re gonna have to go someplace else.’”7

“Someplace else” was also where O’Neil had to go for an education. Sarasota High School was not one of the only four high schools in the state of Florida that would accept African-Americans. “When I finished elementary school in 1926,” he recalled, “my grandmother sat me down and said, ‘John, you can’t go to Sarasota High School. Sarasota High School is not for black kids.’ I shed a few tears at the time, but she said, ‘Don’t cry. One day all kids will go to Sarasota High School.’”8

O’Neil received a scholarship to Edward Waters College, a black school in Jacksonville. Baseball coach Ox Clemons nicknamed him “Country” and also made him a lineman on the football team. O’Neil attained his high school diploma and two years of college. O’Neil also briefly played for the semipro Tampa Black Smokers in 1933. In 1934 he signed to play for the Miami Giants. They were owned by a Buck O’Neal (with a different spelling).9 The Giants were an unofficial minor league club for the Negro Leagues. O’Neil made $10 per week plus room and board on the barnstorming team.10

In 1935 O’Neil joined the New York Tigers. “We had nothing to do with New York,” O’Neil confessed, “but we figured the name would get us some attention from the people fascinated with Harlem. Out west where we were headed, nobody was going to know the difference.”11 The Tigers barnstormed the country in two old Cadillacs, but one had to be sold to pay rent and the other broke down. The players hitched rides and hopped trains, playing in the Denver Post and National Baseball Congress (Wichita, Kansas) semipro tournaments. “Since hobos were a common sight in the Depression, we didn’t have any trouble,” O’Neil said.12 It was in Wichita where O’Neil first met his soon-to-be lifelong friend, Satchel Paige, whose pitching dominated the tournament and brought the championship to his racially-integrated team from Bismarck, North Dakota.

The Tigers lived hand-to-mouth, sometimes depending on O’Neil’s ability to win games of pool to make enough money for the guys to eat. He had learned to play pool at the pool hall next to his parent’s restaurant. The players once snuck out a window of a boarding house when they couldn’t afford the bill. O’Neil left the landlady a note, promising to pay her when they had the money. She never cashed the check he sent, and upon returning years later O’Neil found that the check had been framed.13

In 1936 O’Neil joined the Acme Giants, an unofficial minor league team for the Kansas City Monarchs in Shreveport, Louisiana. When the season concluded, some of the team joined the Texas Black Spiders from Mineola, Texas, who needed players for a trip to Mexico. The team played well and were offered a chance to join a Mexican league if they won an exhibition game. But the Spiders lost and had to return to the US. “You know it’s a tough league when they deport you for losing,” O’Neil joked.14

In 1937 he played for the Memphis Red Sox of the new Negro American League. O’Neil also made more money when he joined the Zulu Cannibal Giants of Louisville, Kentucky. Owner Abe Saperstein’s players wore grass skirts, war paint and nose rings while “acting like a bunch of fools to draw white folks to the park,” O’Neil remembered.15 Saperstein is famous for creating the Harlem Globetrotters. “We would do anything to play ball,” O’Neil admitted. “We had become conditioned to racism. Hatred will steal your heart, man. You don’t have any fight left in you. You accept what’s around you. That’s what this country was like. We thought it would change someday. We just waited for it to change.”16 Fortunately, the racial humiliation didn’t last long. One lasting significance from the Zulus, however, was the fact O’Neil was mistaken for his old team owner Buck O’Neal. “My name went up on the placards as Buck O’Neil,” he said concerning his new nickname, “and it’s been that way ever since, although the black papers didn’t get around to calling me that for a while.”17

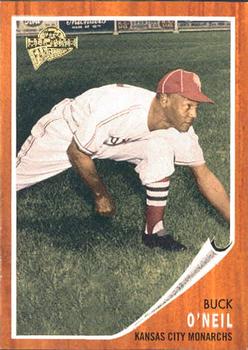

The Kansas City Monarchs came to Shreveport in the spring of 1938. Kansas City’s pioneering owner, J.L. Wilkinson, the only Caucasian team owner in the Negro Leagues, gave O’Neil a tryout. He soon began his legendary career at first base with Monarchs, a powerhouse of Negro League baseball. The team stayed in a hotel at Kansas City’s famous 18th and Vine area, where O’Neil rubbed elbows with musical greats Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday, and Bojangles Robinson, as well as boxer Joe Louis. It seemed like the center of the universe. “New Orleans might have been the birthplace of Jazz,” O’Neil said, “but Kansas City is where it grew up. At 18th and Vine, you couldn’t toss a baseball without hitting a musician, and you couldn’t whistle a tune without having a ballplayer join in. Baseball and jazz, two of the best inventions known to man, walked hand in hand along Vine Street.”18 O’Neil’s debut came in a doubleheader on May 15 before 6,000 fans at Ruppert Stadium in Kansas City as the Monarchs took on the Chicago American Giants. He played right field in the opener and went 1-for-4 in a 4-2 loss. “In the second game,” he remembered nearly 60 years later, “I played first. A dozen years later, I was still there.” He also had a single and an RBI in that nightcap, a 3-0 win.19

From 1939-1942, the Monarchs won four straight Negro American League pennants, with the 1942 team being the greatest team O’Neil believed he ever played on. “I do believe we could have given the New York Yankees a run for their money that year,” he boasted.20 That season O’Neil was also voted by the fans as the starting first baseman for the West squad at the annual East-West All-Star Game. The Monarchs swept the Homestead Grays in the Negro League World Series.

Satchel Paige joined the Monarchs in 1939 and O’Neil, in an oft-told story, earned the nickname “Nancy” from him. Paige had met a young lady named Nancy while the team was in Chicago and invited her to his hotel room. O’Neil suddenly realized Paige’s fiancé Lahoma was making an unexpected visit. He did some quick thinking, moving Nancy to a room next his. In the middle of the night, Paige came knocking on Nancy’s door, calling out, “Nancy! Nancy!” O’Neil heard Paige’s door opening and knew Lahoma was curious to see what was going on. O’Neil bolted up and opened his door, asking, “Yeah, Satch. What do you want?” Realizing Buck had just saved his hide, Paige responded, “Why Nancy. There you are.” Forever after, Paige called O’Neil “Nancy.”21

On Easter Sunday, 1943, O’Neil hit for the cycle against Memphis. The day was memorable for him, however, for what happened that night. He met school teacher Ora Lee Owens, who became the love of his life. Her father was a freed slave and a farmer who had lost everything during the Depression. “That was my best day,” O’Neil said. “I hit for the cycle and I met my Ora.”22

Their relationship became a long-distance one as O’Neil was drafted into the Navy that year. He was assigned to the Stevedore Battalion. “Our job was to load and unload ships,” the veteran remembered, “first in the Mariana Islands and then at Subic Bay in the Philippines.”23 He saw the same type of segregation in the Navy as he saw in the Jim Crow South. “Our own government, which was putting our lives on the line for freedom, was the one telling us to sit at the back of the bus,” he said. “If I had captured a Japanese prisoner, I do believe the Navy would have treated him better than it did me.”24 O’Neil was a Bosun (or Boatswain) First Class officer responsible for a crew of a dozen men. He was once complimented on his leadership skills. “If you were white, you’d be an officer by now,” he was told.25

O’Neil spent his free time writing letters home to Ora, who accepted his proposal for marriage when the war was over. Friends also sent him clippings from the black newspapers so he could stay updated on the Monarchs. “The Negro Leagues didn’t exist as far as the Stars and Stripes (the newspaper of the armed forces) was concerned,” O’Neil said.26 In those clippings, he learned about a rising star on the 1945 Monarchs, Jackie Robinson, who tore up the league with a .384 average. Later that fall, O’Neil was summoned by his commanding officer. “I just thought you should know that the Brooklyn Dodgers have just signed Jackie Robinson,” he told O’Neil. “He’s going to play for their minor league team in Montreal next year.” Overjoyed, O’Neil jumped on the intercom and announced the news to the crew. “We started hollering and shouting and firing our guns into the air,” he remembered. “I don’t know that we made that much noise on VJ Day. This was progress for the whole country. It didn’t matter who was the first or which team had the courage; this was the real first step toward integration, toward equality, since maybe Reconstruction.”27

O’Neil came home and married Ora on January 17, 1946. “Her parents didn’t want her to marry a ballplayer, you know,” he recalled six decades later. “But I won them over. Her father asked me what my father did. I told him: ‘He’s in recreation.’ And he was too. He ran a pool hall. He did some bootlegging. You know…recreation.”28

After spring training, the newlyweds moved to Kansas City and Ora secured a teaching job. Buck returned to his familiar first base position for the Monarchs, who played the Newark Eagles in the World Series. The series went back and forth and concluded with a Game Seven in Newark before 7,500 fans. O’Neil, never a power hitter, hit his second home run of the series in the sixth inning to tie the score, 1-1.29 Newark won the tight contest, 3-2, their only Negro League championship. Wilkinson, who had created the franchise in 1920, sold out his ownership shares to long-time partner Tom Baird, who then named the 36-year-old O’Neil as player-manager.30 Traveling secretary Dizzy Dismukes helped Buck understand his new role as “some guys need pats on the back, some guys need kicks in the butt, and some guys just plain need to be left alone,” O’Neil said. “And some guys need all three.”31

O’Neil guided the Monarchs to the Negro American League championship, winning the first half of their season while Birmingham won the second half. They played each other in a seven-game series, won by Birmingham, which went on to win the final Negro League World Series over the Homestead Grays.

The Negro National League folded that offseason. The Monarchs were still successful into the early 50s, but by then the existing Negro American League was a shell of its former greatness. To survive, clubs needed to act as minor league teams, discovering young talent they could then sell to major league teams for profit. Besides handling expenses, schedules, travel arrangements and personnel matters, O’Neil now needed to become a scout to keep the team afloat. Integration meant newspapers provided very little coverage of the Negro Leagues, which were greatly depleted.

Still, O’Neil discovered and mentored some of the greatest players in baseball history. When New York Yankees scout Tom Greenwade came looking to sign Willard Brown, Buck steered him in another direction. “The player you should be looking at is our young catcher,” he told him. For $25,000 Elston Howard became the first African-American New York Yankee, enjoying a 14-year, all-star filled career.32 In 1950, Cool Papa Bell told O’Neil that he needed to go see a 17-year-old shortstop playing for the Black Sheepherders in San Antonio, Texas. O’Neil drove to Dallas and signed the prospect without even seeing him play. “Cool’s word was good enough for me,” O’Neil said. “Turns out it was good enough for the Hall of Fame. The young man was Ernie Banks.”33 After a couple of years in the military, Banks returned to the Monarchs and now attracted great attention around baseball. So, in 1953, the Chicago Cubs offered the Monarchs $20,000 for the man who would become “Mr. Cub.” “Buck O’Neil helped me in many ways. He installed a positive influence,” Banks said.34 “He was a delight right from the start, on the field and off,” O’Neil remembered of Banks.35

Still, O’Neil discovered and mentored some of the greatest players in baseball history. When New York Yankees scout Tom Greenwade came looking to sign Willard Brown, Buck steered him in another direction. “The player you should be looking at is our young catcher,” he told him. For $25,000 Elston Howard became the first African-American New York Yankee, enjoying a 14-year, all-star filled career.32 In 1950, Cool Papa Bell told O’Neil that he needed to go see a 17-year-old shortstop playing for the Black Sheepherders in San Antonio, Texas. O’Neil drove to Dallas and signed the prospect without even seeing him play. “Cool’s word was good enough for me,” O’Neil said. “Turns out it was good enough for the Hall of Fame. The young man was Ernie Banks.”33 After a couple of years in the military, Banks returned to the Monarchs and now attracted great attention around baseball. So, in 1953, the Chicago Cubs offered the Monarchs $20,000 for the man who would become “Mr. Cub.” “Buck O’Neil helped me in many ways. He installed a positive influence,” Banks said.34 “He was a delight right from the start, on the field and off,” O’Neil remembered of Banks.35

“Toward the end,” O’Neil recalled of his last years in Kansas City, “the league got so raggedy that I used myself as a pitcher.” After winning his first game, he started himself again the next day. “Buck O’Neil the pitcher might still be out there if Buck O’Neil the manager hadn’t taken him out after goodness knows how many runs and just a few innings.”36 In 1955, Baird sold the Monarchs to Ted Rasberry, who turned the club into a barnstorming team based out of Michigan. The Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City the same year, so now local baseball fans had a major league team to cheer for. For at least a three-year period (1953-1955), O’Neil managed the West squad at the annual All-Star game of the Negro American League.37

At the end of the 1955 season, O’Neil’s long association with the Kansas City Monarchs came to an end. His statistics, like all statistics from the Negro Leagues, are incomplete and often fail to tell the true story. There were so many games in so many places, and O’Neil believed his best games were never recorded. “I was a .300 hitter, no doubt,” he said. The Seamheads Negro Leagues Database gives O’Neil a lifetime batting average of .262, while Baseball-Reference.com credits him with a .283 average and the Center for Negro League Baseball Research gives the highest projection of .303.38 The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum credits O’Neil with a .288 career average. O’Neil also led the Negro American League in batting with a .353 average in 1946.39 Whichever statistical source is used, it is agreed O’Neil was a solid contact hitter who played fine defense at first base.

O’Neil was signed to scout for the Chicago Cubs at the end of the 1955 season. He would focus on the South, looking for African-American players who would feel at ease with his visits. He would also work with players during spring training as well as drive around in his Plymouth Fury looking for talent wherever his hunches would lead him. Whereas today scouting is based on statistics and advanced analytics, O’Neil depended on his instincts, which led him to some excellent and even legendary players.

One day in 1968 O’Neil watched a group of unimpressive semipro players in Montgomery, Alabama. On his way out he saw a small, skinny, 18-year-old. There was something about how this kid maneuvered on the field. O’Neil raced out to him to say hello. “I’m Buck O’Neil, a scout for the Cubs,” he said. “And I want to see you play.” The youngster stuttered and tripped over his words trying to explain how to find a field he would be playing at the next day. O’Neil drove down the dusty back roads until he found a beautiful little park with people sitting on lawn chairs. He stayed in his car and just watched one at-bat. It didn’t matter that the kid flied out—O’Neil saw his bat speed, his timing, and heard the crack of his bat. He sped off immediately to go file his report to the Cubs, describing this kid from the Alabama woods they needed to sign. “It’s a great name, isn’t it?” O’Neil said when recounting the story. “Oscar Gamble! That sounds like a ballplayer. And he was. He was a heck of a ballplayer.” Gamble would go on to a memorable 17-year career and become a postseason hero.40

O’Neil also watched a freshman at Southern University who struggled at the plate but had tremendous speed. Despite his up-and-down success at the plate, O’Neil promised he would top any offer from another team. “He got me started on a journey that became a 19-year major league baseball career,” said Lou Brock, a future Hall-of-Famer. “He shaped the character of young black men. He touched the heart of everyone who loved the game. He gave us all a voice that could be heard on and off the field. We who were close to him will forever seek to walk in the shade of his shadow.”41

The Chicago Cubs promoted O’Neil to its major league coaching staff in 1962, making Buck the first African-American coach to serve on a major league roster.42 Such an accomplishment earned him recognition in both Sports Illustrated and Ebony. “When a fellow makes a mistake,” O’Neil told Ebony, “you don’t ride him. You show him what he’s supposed to do and make him believe he can do it. You have to make him believe in himself.”43

It was difficult to believe the Cubs managerial situation. The unique setup of owner Phil Wrigley had a regular rotation among several coaches to take the stress off of one individual. “It was a ridiculous idea,” O’Neil said long after the fact, “although I was quoted in the Ebony article as saying it was a ‘wonderful innovation’ that would ‘be adopted by most teams.’ What was I supposed to say?”44 O’Neil was told he would become part of the rotation, which would have made him the first African-American to manage a major league game, but the promise wasn’t fulfilled and it would be over a decade before a major league team would hire a minority manager.

O’Neil returned full time to scouting with the Cubs in 1964, where he remained through the 1988 season. Two future stars he signed were Hall of Fame closer Lee Smith, who finished with 478 career saves, and Joe Carter, who slammed 396 home runs and became a World Series hero.

O’Neil planned to retire after the 1988 season. Ora had retired in 1983 after 31 years of teaching in the Kansas City Public School system. But then he got a call from the Kansas City Royals and was soon scouting for the team in the city he had first moved to 50 years before, long before the days of million-dollar salaries and television broadcasts. “I’ve been fortunate enough to make my living at something I’ve loved,” O’Neil said. “When I started I was making $100 a month, with $1 a day for meal money. But in those days you could get breakfast for 25 cents and dinner for 35 cents. We didn’t eat more than two meals a day.”45

While much had changed over his lifetime, the crack of the bat was the same as ever for O’Neil. He remembered distinct cracks that became milestones in his life. As a boy in St. Petersburg he clearly remembered the sound “like a small stick of dynamite going off” when Babe Ruth was batting. He heard the sound again in 1938 and ran out to the field to see Josh Gibson at the plate. Now with the Royals 50 years later, he heard the same crack from Bo Jackson’s bat. “I’m going to keep going to the ballpark until I hear that sound again,” was O’Neil’s promise.46

O’Neil also worked tirelessly towards the creation of a permanent Negro Leagues museum. The original museum began in a small, one-room office in 1990. O’Neil and Kansas City Royals legend Frank White were among the original board of directors and they took turns paying the rent.47 A better facility was needed. “If we don’t do something with the museum, the memory of black baseball is going to die,” he said. “All that’s left is a few of us, and we’re losing them every year. We’re going to preserve stuff that’s in attics and going to rot and guy’s grandkids are going to throw out. It’s kind of an exciting time around here for me right now.”48 A new expanded museum opened in 1994.49

A month later, millions of people discovered O’Neil for the first time thanks to film director Ken Burns’ epic nine-part documentary series Baseball, produced for Public Television. “I think what I have talked about are the same things I have talked about for a long time, but now someone is listening,” O’Neil said about the large audience which could now hear his stories. “I’ve been talking about this for 60 years. Now I’ve got an ear.”50 O’Neil became a celebrity of sorts, a living legend who traveled with Burns to promote the film. “It’s kind of nice to be discovered when you’re eighty-two years old,” he said.51 Burns remembered the awe surrounding O’Neil when they met for the interviews. “There’s nothing you can say about Buck O’Neil that one second in his presence won’t prove a hundred times over,” Burns said. “It is impossible to resist the positive force that lights him from within and then spreads out and lights and warms you, too.”52

In 1995 Buck returned to Sarasota High School to finally receive his diploma. “Sixty-nine years after I cried because I couldn’t go to Sarasota High School, I was crying because I was about to graduate,” O’Neil said. “I was almost too choked up to speak. But I did. I told those students that I had talked to my parents and my sister the day before. And in my conversation, I let Mamma and Papa and Fanny know that I would be going to Sarasota High School the next day to graduate. You can’t see them, I told the students, but they’re here today. I feel them.”53

Kansas City began plans for an expanded facility to house both the Negro Leagues Museum and the new American Jazz Museum.54 The project was part of Kansas City’s revitalization of the historic 18th and Vine district. The new museum opened November 1, 1997.55 For all the hard work that had gone into the museum, it was a somber time for O’Neil; Ora passed away from cancer the following day after 51 years of marriage.56 She had battled the disease the last 15 years of her life but was committed to her dream to live long enough to see the project to its finish. “’She said I made it,” O’Neil recalled. “And she died in my arms.”57

Buck O’Neil continued scouting through the 1990s and was named the Midwest Scout of the Year in 1998.58 In 2001, the Kansas City area celebrated Buck’s 90th birthday by renaming a street “John ‘Buck’ O’Neil Way” and hearing best wishes read from President George W. Bush.59

An unlikely friendship developed in 2001 as O’Neil welcomed Japanese hitting star Ichiro Suzuki to the Negro Leagues Museum. Ichiro noticed the well-dressed man hanging around the batting cages when the Mariners visited Kauffman Stadium. They were from two totally different cultures, eras, and bank accounts: the multi-millionaire star from Japan and the poor boy from the Jim Crow south. Yet O’Neil, as he did in many situations, connected with people from all walks of life. “With Buck, I felt something big,” Ichiro said. “The way he carried himself, you can see and tell and feel he loved this game. And when you see that presence, it makes you want to know more about him.”60 The two formed a close friendship.

O’Neil spent the days around his 94th birthday in 2005 traveling to Washington D.C. and speaking before Congress, asking for an official proclamation that the Negro Leagues Museum be designated as America’s Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.61

In 2006, O’Neil was still listed in the Royals Media Guide as a part-time scout.62 It is believed that O’Neil scouted 13 eventual major leaguers over his career.63 Sportswriter Joe Posnanski had the priceless opportunity to travel with O’Neil across the country for speaking engagements and other events to promote the Negro Leagues. Their road trip is chronicled in Posnanski’s book The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck O’Neil’s America.

On one occasion, the duo were parked at 18th and Vine. Despite the attempts at revitalization, it was still just a shell of its glory days. O’Neil was now the last of the Kansas City Monarchs from the 1930s, but the images were still fresh in his mind. “One day I was walking around here with Duke Ellington,” he recalled of the Jazz legend. They went into a club and “we hear this chubby Kansas City kid blowing on his saxophone. He played it fast and wild and all over the place.” It was another Jazz legend: Charlie Parker. “People feel sorry for me,” O’Neil said. “Man, I heard Charlie Parker.”64

O’Neil served as a representative of the Negro Leagues on the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee from 1981-2000, and 11 Negro Leagues players were inducted through 2001 for a total of 18. Yet there was still a feeling that many more had been missed.65 In 2000, Major League Baseball supplied a grant to the Baseball Hall of Fame to conduct extensive research on the history of the Negro Leagues. This fruitful work led to 9,500 pages of compiled data on games and over 6,000 players, information now available to the modern researcher. This work also led to the formation of a committee in 2005 to consider Negro League players and executives who deserved to be inducted into the Hall of Fame the following year.66 Many felt O’Neil was long overdue for election because of his many contributions in representing the Negro Leagues. There was public outrage, especially in the Kansas City area, when he missed election by one vote.

“All his life,” wrote Posnanski in the Kansas City Star, “Buck O’Neil has had doors slammed in his face. He played baseball at a time when the major leagues did not allow black players. He was a gifted manager at a time when major league owners would not even think of having an African-American lead their teams. For more than 30 years, he told stories about Negro League players and nobody wanted to listen. Now, after everything, he was being told that the life he had spent in baseball was not worthy of the Hall of Fame. It was enough to make those around him cry. But Buck laughed.” O’Neil simply said, “That’s the way the cookie crumbles. I’m still Buck. Look at me. I’ve lived a good life. I’m still living a good life. Nothing has changed for me.”67

“You know why Buck is alive today, playing golf, driving his Caddy, traveling the globe and enjoying unprecedented popularity and support?” asked writer Jason Whitlock. “Because he never got swallowed by anger, because he never allowed other people’s behavior to dictate his behavior, because he refused to view himself as a victim. He’s no victim today.”68 While O’Neil exhibited no anger, the same could not be said for Ernie Banks. “All of those people whose lives he touched and played with . . . it is a travesty. It really hurt my heart. It hurt me. I wish I could surrender my election to baseball’s Hall of Fame to him, because I always felt that he deserved it more than I did.”69

While friends took swings at the seemingly neglectful committee, O’Neil took his final swings at the plate. O’Neil actually played in the All-Star game of the Northern League, an independent professional league, in Kansas City, Kansas, on July 18. The 94-year-old, batting leadoff for the West club, took a couple of pitches before drawing the planned intentional walk. He was quickly replaced, then was “traded” to the Kansas City T-Bones, allowing him to lead off the bottom of the first. He drew his second walk of the game.70

O’Neil took to the podium at the Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony at the end of July to speak for the 17 Negro League players and executives who never lived to see such recognition. “I’ve been a lot of places,” he said. “I’ve done a lot of things I really liked doing … but I’d rather be right here, right now, representing the people who helped build a bridge across the chasm of prejudice.” He added, “I’m proud to have been a Negro Leagues ballplayer.” In his last few minutes on stage, O’Neil asked the Hall of Famers behind him and the audience to join hands as he led them in singing, “The greatest thing in all my life … is loving you.”71

It was a fitting conclusion to Buck O’Neil’s life. He passed away on October 6, 2006, just shy of his 95th birthday. He had, as even he said, lived “a full life.”72 A funeral was held at the African Methodist Episcopal church in Kansas City which the O’Neils had attended since 1947. Thousands attended a public memorial service held later that day at Kansas City’s Municipal Auditorium.73 Many of his words were recalled, including these:

People ask me: How do you keep from being bitter? Man, bitterness will eat you up inside. Hatred will eat you up inside. Don’t be bitter. Don’t hate. My grandfather was a slave. He was not bitter. I learned that from him. And you know what? I wouldn’t trade my life for anybody’s. I’ve had so many blessings in my life. I don’t want people to be sad for me when I go. Be sad for the kids who die young. You shouldn’t feel sad for a man who lived his dream. You know what I always say? I was right on time.74

Awards and recognitions continued to come for O’Neil. He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, by President George W. Bush. “A beautiful human being,” Bush said of O’Neil, with Warren O’Neil accepting the award on his brother’s behalf. “Buck O’Neil lived long enough to see the game of baseball, and America, change for the better. He’s one of the people we can thank for that.”75 In 2008, the Baseball Hall of Fame unveiled a life-sized statue of O’Neil placed inside the front entrance, and also introduced the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award, presented every three years “to honor an individual whose extraordinary efforts enhanced baseball’s positive impact on society, broadened the game’s appeal, and whose character, integrity and dignity are comparable to the qualities exhibited by O’Neil.”76

A bust of O’Neil was placed in the third-floor rotunda at the Missouri state capitol of Jefferson City and he was inducted into the Hall of Famous Missourians. “There is no doubt that he (O’Neil) belongs here among the greatest citizens in the history of our state,” House Speaker Steven Tilley said.77 In 2016, Kansas City’s Broadway Bridge was renamed the Buck O’Neil Bridge.78 O’Neil’s legacy also lives on in a physical way at Kauffman Stadium. The very seat he occupied behind home plate was designated the Buck O’Neil Legacy Seat. The seat is filled for every Royals home game by “a member of the community who, on a large or small scale, embodies an aspect of Buck’s spirit.”79

The former YMCA building near 18th and Vine which served as the site of the founding of the Negro National League in 1920 became the Buck O’Neil Research and Education Center in 2017.80 The facility provides educational programs for students. In the summer of 2018, vandals caused $500,000 damage to the facility. An outpouring of financial support, called a “Buck-like” measure of love, followed “to heal and focus on what can be done instead of what went wrong,” wrote Vahe Gregorian of the Kansas City Star.

Finally, in December 2021, O’Neil was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Early Baseball Era Committee as part of the Class of 2022.

And the stories continue, right on time.

Related links:

- Listen to Buck O’Neil’s speech from the 1996 SABR convention in Kansas City (SABR Oral History Collection)

- Listen to Buck O’Neil’s Oral History interview with Fay Vincent from August 22, 2000 (SABR Oral History Collection)

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the notes, special thanks are given to Cassidy Lent, reference librarian at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame. Other sources include:

Baseball-Reference.com

Seamheads Negro Leagues Database

Wulf, Steve. “The Guiding Light: Buck O’Neil Bears Witness to the Glory and Not Just the Shame of the Negro Leagues,” Sports Illustrated, September 19, 1994: 169-179.

Notes

1 Buck O’Neil with Steve Wulf and David Conrads, I Was Right on Time (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 4.

2 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 3.

3 Lawrence D. Hogan, Shades of Glory: The Negro Leagues and the Story of African-American Baseball.

4 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 17-19.

5 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 17-24.

6 Interview with Ken Burns. pbs.org/kenburns/baseball/shadowball/oneil.html Retrieved November 25, 2018.

7 Interview with Burns.

8 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 230.

9 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 12.

10 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 36-42.

11 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 46.

12 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 55.

13 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 52-54.

14 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 66.

15 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 66.

16 Joe Posnanski, The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip Through Buck O’Neil’s America (New York: Harper, 2007), 21.

17 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 73.

18 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 76.

19 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 86; “No Run off Kranston,” Kansas City Times, May 16, 1938: 12.

20 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 119.

21 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 14-15.

22 Joe Posnanski, “A KC Legend Dies—Baseball Icon ‘Lived a Full Life’ as he Came to Symbolize the Glory of the Negro Leagues,” Kansas City Star, October 7, 2006: 1.

23 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 159.

24 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 159.

25 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 160.

26 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 162.

27 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 165.

28 Posnanski, The Soul of Baseball, 50.

29 “Newark Eagles New Diamond Champs,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 5, 1946: 15.

30 “A Ball Club Sale,” Kansas City Star, February 12, 1948: 20.

31 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 186.

32 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 189; Cecilia Tan, “Elston Howard.” SABR BioProject. sabr.org/bioproj/person/e6884b08 Retrieved November 22, 2018.

33 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 189-190.

34 Joseph Wancho, “Ernie Banks.” SABR BioProject. sabr.org/bioproj/person/b8afee6e Retrieved November 22, 2018.

35 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 190.

36 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 195-196.

37 “O’Neil Named Pilot of Negro West Squad,” Chicago Tribune, July 10, 1955: A4.

38 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: John ‘Buck’ O’Neil,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, 2013. www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/John-Buck-ONeil.pdf; Thanks to Gary Ashwill of the Seamheads database for providing context on these statistics.

39 “John ‘Buck’ O’Neil,” nlbemuseum.com/history/players/oneil.html

40 Joe Posnanski, “Gamble Made Legendary O’Neil Proud,” mlb.com/news/oscar-gamble-made-buck-oneil-proud/c-265614542 Retrieved November 23, 2018.

41 Associated Press, “Brock, Others, Remember Buck O’Neil at Funeral,” October 15, 2006. espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=2625618 Retrieved November 22, 2018.

42 Richard Dozer, “Cubs Sign Negro Coach,” Chicago Tribune, May 30, 1962: 47.

43 “First Negro Coach in Majors,” Ebony 17, no. 10 (1962), 29; The Sports Illustrated blurb was in “Faces in the Crowd,” (June 24, 1962), 75.

44 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 213.

45 Laura R. Hockaday, “Baseball Has Changed a Lot in 53 Years. Buck O’Neil, Formerly a KC Monarch, Recalls $100-a-month Salaries,” Kansas City Star, November 24, 1991: F4.

46 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 3-4.

47 Maria Torres, “Royals Legend Frank White will be Honored with Buck O’Neil Legacy Award,” kansascity.com/sports/mlb/kansas-city-royals/article181136991.html Retrieved January 19, 2019; Jack Etkin, “Negro Leagues to be Preserved. Museum Set to Unveil an Early-Day Display of Black Baseball Stars,” Kansas City Star, February 12, 1991: C1; Jack Etkin, “Museum Looks for Support,” Kansas City Star, June 21, 1990: D1.

48 Jack Etkin, “In More Ways Than One, O’Neil Holds Special Spot; Ex-KC Monarch has Seat, Ideas of His Own in Role as Royals Scout,” Kansas City Star, September 8, 1991.

49 Howard Richman, “Museum Has Grand Beginning; Negro Leagues Stars Now at 18th and Vine For Everyone to See,” Kansas City Star, August 6, 1994: D1.

50 La Velle E. Neal III, “A Star is Born…at 82. ‘Baseball’ Becomes O’Neil’s Private Forum,” Kansas City Star, September 22, 1994: D1.

51 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 2.

52 , xiii.

53 O’Neil, Wulf, and Conrads, 232-233.

54 “About NLBM,” nlbm.com/s/about.htm Retrieved November 25, 2018.

55 Yael T. Abouhalkah, “Baseball’s Champion Buck O’Neil Stands Tall as Negro League Museum Opens,” Kansas City Star, October 31, 1997: C6.

56 Tom Smith, “Big Weekend Turns Sad for O’Neil,” Kansas City Star, November 3, 1997: C2.

57 Randy Covitz, “Buck and Ora Were About Love,” Kansascity.com, October 8, 2006. kansascity.com/sports/article295461/Buck-and-Ora-were-about-love.html Retrieved December 1, 2018.

58 Dick Kaegel, “Pitching Coach Kison is Fired by the Royals,” Kansas City Star, October 21, 1998: D5.

59 Joe Posnanski, “This Buck Won’t Stop—This KC Legend May be 90, but the Stories Keep Coming—Like the One About…” Kansas City Star, November 14, 2001: D1.

60 Jeff Passan, “Ichiro Draws From Lessons Learned From Friend Buck O’Neil as He Ponders Future with Mariners,” Yahoo Sports, July 19, 2012. yahoo.com/news/ichiro-draws-from-lessons-learned-from-friend-buck-o-neil-as-he-ponders-future-with-mariners.html Retrieved December 1, 2018.

61 Joe Posnanski, “Politicians Pay Attention When Mr. O’Neil Goes to Washington,” Kansas City Star, November 16, 2005: D1.

62 Jeffrey Flanagan, “O’Neil to Royals Hall Would Be a Nice Gift,” Kansas City Star, September 26, 2006: C2.

63 Thanks to Rod Nelson of the SABR Scouts Research Committee for this information.

64 Posnanski, The Soul of Baseball, 38.

65 “Past Inductions,” baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/past-inductions/past-inductions

66 “Negro League Researchers and Authors Group,” baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/rules/759 Retrieved January 19, 2019.

67 Joe Posnaski, “Injustice, and Then a Gutless Committee Clams up,” Kansas City Star, February 28, 2006: A1.

68 Jason Whitlock, “Buck’s Love Overpowers the Injustice,” Kansas City Star, March 1, 2006: D1.

69 “Buck O’Neil, 1911-2006,” Chicago Tribune, October 8, 2006.

70 Associated Press, “At 94, O’Neil Oldest-Ever Pro Baseball Player,” Hays Daily News (Kansas), July 19, 2006: 11.

71 Bob Dutton, “Showstopper—Buck O’Neil Puts Personal Disappointment Aside as He Celebrates the Lives of Other Negro League Legends During Induction Ceremony,” Kansas City Star, July 31, 2006; C1.

72 Posnanski, “A KC Legend Dies,”

73 Associated Press, “Brock, Others Remember Buck O’Neil at Funeral,” October 15, 2006. espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=2625618 Retrieved November 25, 2018.

74 Joe Posnanski, “Farewell, Old Friend—The Man Who Was More Than a Baseball Great is Gone, But he Leaves a Legacy of Living, Loving,” Kansas City Star, October 15, 2006: A1.

75 Matt Stearns, “Bush Confers Honor on Buck—He is Awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Nation’s Highest Civilian Honor,” Kansas City Star, December 16, 2006: 1; The citation reads:

“Buck O’Neil represented excellence and determination both on and off the baseball field. Rising above the injustice of a segregated country and sport, he served his Nation in World War II, was a talented player and manager in the Negro Leagues, and was Major League Baseball’s first African-American coach. As a co-founder of and inspiration for the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, he served as the Museum’s Chairman of the Board and worked to ensure that generations of baseball legends would not be forgotten. The United States posthumously honors John ‘Buck’ O Neil for his generous spirit, devotion to baseball, and unyielding commitment to equality.”

76 “Buck O’Neil Award,” baseballhall.org/discover-more/awards/890 Retrieved November 25, 2018.

77 Wes Duplantier, “Buck O’Neil Honored as a Famous Missourian,” kansascity.com/news/local/article301253/Buck-ONeil-honored-as-a-famous-Missourian.html Retrieved November 27, 2018.

78 Andrew Lynch, “A Dream Come True: Broadway Bridge Renamed for Monarchs Legend Buck O’Neil,” fox4kc.com/2016/06/24/a-dream-come-true-broadway-bridge-renamed-for-monarchs-legend-buck-oneil/ Retrieved November 25, 2018.

79 “Buck O’Neil Legacy Seat Program.” mlb.com/royals/community/buck-oneil-seat Retrieved December 22, 2018.

80 Editorial Board, “Vandals Damaged Buck O’Neil Center. KC Should Rally Around a Baseball Legend’s Vision,” Kansas City Star, June 26, 2018.

Full Name

John Jordan O'Neil

Born

November 13, 1911 at Carrabelle, FL (US)

Died

October 6, 2006 at Kansas City, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.