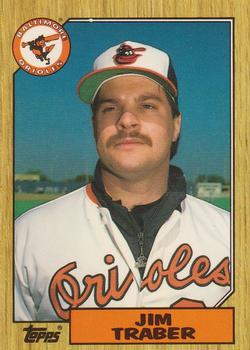

Jim Traber

When Orioles’ first baseman Eddie Murray went on the disabled list for the first time in his Hall of Fame career in July 1986, Baltimore turned to a player who had grown up just a 30-minute drive from Memorial Stadium. In Jim Traber’s first 17 games, the brash, left-handed-swinging rookie whacked eight homers, drove in 22 runs and helped the Orioles climb from nine games out to within two-and-a-half games of the AL East lead. The timely hot streak made Traber — nicknamed “The Whammer” — a local folk hero, but his opportunities to play dwindled in ensuing seasons and he eventually became a top-rated sports talk show host in Oklahoma.

When Orioles’ first baseman Eddie Murray went on the disabled list for the first time in his Hall of Fame career in July 1986, Baltimore turned to a player who had grown up just a 30-minute drive from Memorial Stadium. In Jim Traber’s first 17 games, the brash, left-handed-swinging rookie whacked eight homers, drove in 22 runs and helped the Orioles climb from nine games out to within two-and-a-half games of the AL East lead. The timely hot streak made Traber — nicknamed “The Whammer” — a local folk hero, but his opportunities to play dwindled in ensuing seasons and he eventually became a top-rated sports talk show host in Oklahoma.

James Joseph Traber was born on December 26, 1961, in Columbus, Ohio. His father, Peter Traber, who had begun life in Pittsburgh as Peter Trbovich, the son of Serbian immigrants from Yugoslavia, was an engineer for the Federal Highway Administration. His mother, Florence (Garfall), the daughter of an Italian immigrant, grew up in Johnstown, New York. A teacher, she was also a multi-talented athlete. Jim was the youngest of three children, following Theresa, who became a lawyer and judge, and Peter, who became a doctor,

In 1969, the Traber family moved to Columbia, Maryland, about 25 miles southwest of Baltimore.1 The Baltimore Orioles began a string of three consecutive American League pennants that year, and Jim soon played his first Little League baseball. As a teen, he earned Howard County All-Star honors in American Legion ball. Traber also joined Baltimore’s famed Johnny’s team — the amateur outfit boasting Reggie Jackson and Al Kaline among its alumni — for part of one summer before it was time for him to prepare for football season.

At Wilde Lake High School, Traber earned all-county baseball recognition all four years and all-metro honors for the Baltimore area twice. In 1979 he became the first person to win both the Evening Sun’s high school athlete of the year and the Scholar Athlete Award. The multi-talented Traber also lettered in football and basketball, played tennis, and won a prize for his excellence in the performing arts. He played roles like Don Quixote, King Arthur, and Buffalo Bill Cody in school productions and sang in the Concert Choir. “If he hadn’t made it in baseball, he’d have made it in singing,” remarked Frank Rhodes, Traber’s baseball and basketball coach at Wilde Lake. “He’d charm a buzz saw.”2

Baseball scout Joe Consoli, a former minor league third baseman and manager, approached him about pro ball, but Traber was determined to go to college. At the Oklahoma State Cowboys’ annual football banquet in February 1979, coach Jimmy Johnson identified Traber — listed as a 5’11”, 190-lb quarterback/defensive back—as one of his incoming recruits.3

Johnson, a 2020 Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee, was starting his first head coaching job that season. By 1994, his resume would include a national championship at the University of Miami and two Super Bowl victories with the Dallas Cowboys. When Traber arrived in Stillwater, Oklahoma State boasted talent like future NFL All-Pro defensive end Dexter Manley, but the program was in the early stages of a rebuild.

As a sophomore in the fall of 1980, Traber — dubbed “Sonny Jurgensen” by his teammates — was OSU’s primary quarterback. “He was overweight, had a little gut on him,” recalled Dave Wannstedt, an assistant coach that season, who later led the Chicago Bears to victory in Super Bowl XLI. “There’s no question he was the team leader. He had a great knack for moving the team and motivating them.”4

On October 11, the left-handed Traber’s 19-yard touchdown pass gave OSU a 7-0 halftime lead against 19th-ranked Missouri, but the Tigers erupted to win, 30-7, behind the Big Eight Conference’s top-rated passer that season, future major-league outfielder Phil Bradley. Four weeks before Traber’s 19th birthday, the season concluded against the powerful Oklahoma Sooners in front of 76,000 on Senior Day. “Now that’s pressure,” Traber said.5 The Cowboys lost, 63-14, and finished their season 4-7.

After playing only a little bit of baseball as a freshman, Traber decided to focus on that half of his two-sport scholarship in 1981 and batted a team-best .396 and with a conference-record 26 doubles6. He also ranked as the club leader in home runs and RBIs as Oklahoma State won the first of 16 consecutive Big Eight championships under coach Gary Ward.7 After the Cowboys went to the final of the College World Series and finished the season ranked fourth in the nation, seven players were drafted into the professional ranks in June, including two-time All Star Mickey Tettleton.

Traber quit the football team that fall when Johnson told him he’d slipped to fourth string on OSU’s depth chart. “It was partly because of baseball, too, but mainly because I was getting screwed,” Traber explained.8 In 1982, Traber hit .378 to lead the Cowboys again as the club returned to the College World Series. In the loss that eliminated Oklahoma State, Traber stroked two hits to break his own single-season school record.9 He finished his college career with OSU single-season records for doubles and RBIs, plus school-leading career marks in those categories as well as hits, batting average and slugging percentage, though his records have since been broken,

The Orioles drafted Traber in the 21st round after his junior season, and scout Jim Gilbert signed him. In 61 games with the Rookie-level Bluefield Orioles, Traber batted .323, led the Appalachian League with 30 extra-base hits and tied Yankees’ prospect Dan Pasqua for the circuit’s top RBI total. Never anything approaching a speedster, he even stole 22 bases. After Bluefield clinched the pennant, Traber advanced to the Hagerstown Suns, where he hit .346 in a seven-game trial and sang the national anthem before his Class-A debut.

Traber started slowly for Hagerstown in 1983 after an early-season bout with strep throat but enjoyed a solid season in the Carolina League. On a questionnaire that he filled out that summer, Traber listed playing first base behind Orioles’ legend Jim Palmer — in Hagerstown for a two-game rehabilitation assignment — as his greatest baseball thrill to date. “Ran back to dugout together. Sat next to him and talked with him during game,” Traber reported. “I hit a home run and had two singles in that game to help give him a win!”10

Singing professionally helped Traber pay the bills during the off-season, and he also hustled as a bartender, substitute teacher and short-order cook. After beginning the 1984 season back at Hagerstown, a .358 BA in 48 games earned him a promotion to AA Charlotte, where he batted .351 in 75 Southern League contests and clubbed a team-leading 16 home runs. On September 21, 1984, at Memorial Stadium, Traber sang the “Star Spangled Banner” before a Friday night Orioles-Red Sox contest and made his major league debut. Batting sixth as Baltimore’s designated hitter, he struck out in his first at bat against Boston’s Dennis “Oil Can” Boyd, then stroked a fourth-inning single up the middle for his first big league hit.

After going 5-for-21 in his September call up, Traber accompanied the Orioles to Japan on the club’s 14-game exhibition tour. In 1985, he appeared on his first major league baseball card as a Donruss “Rated Rookie” and reported to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings as the most promising hitting prospect in Baltimore’s organization. A knee injury cost him seven weeks from late May to early July, however, and he finished the season batting .265 in 80 games.

Back at Rochester in 1986, Traber started slowly after an early season groin pull. By mid-July, however, The Sporting News reported that his 55 RBIs ranked second in the International League. When Eddie Murray pulled a hamstring on an Orioles’ road trip, he joined the Orioles in Baltimore after the All-Star break. “I’m not here to sing. I’m here to play this time,” he announced.11

On July 20, Traber notched three hits against the Minnesota Twins, including his first major league homer off Mike Smithson, the three-run shot favored by Orioles’ manager Earl Weaver. Many of the 25, 045 in attendance at Memorial Stadium that Sunday afternoon gave Traber a standing ovation. “I had chills running up and down my spine,” he said. “It’s wonderful to be able to do that in front of the hometown fans.”12

Two nights later against the American League’s reigning Cy Young Award winner, Traber took the Royals’ Bret Saberhagen deep twice. He added two more long balls before the home stand was over, including a grand slam, and became a local folk hero. Traber still lived at his parents’ home in Columbia, just a half-hour drive from Memorial Stadium. “After a game, we take the phone off the hook so he can sleep,” his mother reported.13

By the time Traber blasted another four-bagger in Baltimore’s first game back after a road trip on August 5, he was batting .333 with eight homers and 22 RBIs in just 17 contests, living up to his nickname, “The Whammer.” Meanwhile, the Orioles had climbed from nine games out of first place to within two-and-a-half shortly before Murray, the club’s leading slugger, rejoined the team. “I came up there with the attitude that everything was going to be temporary,” Traber said. “But then I played so well that, when Eddie returned, they kept me around, I thought I had it made.”14

Traber went 4-for-4 the night Murray returned to the lineup and boosted his average to .373 with three more hits the next evening. Then the bubble burst. He batted .190 the rest of the way, dropping his average to .255 as the Orioles sank to the bottom of the A.L. East by going 14-42 down the stretch.

Nevertheless, Traber’s 13 home runs in just 212 at bats opened eyes, and the best year of his professional career got even better when he married the former Joan Sampson and fathered son Trabes. “Everyone thinks it’s this egomaniac giving his kid his nickname, but it’s not,” he explained. “[Joan] said everyone was going to call him ‘Little Trabes’ anyway, so why not name him that?”15

With Murray healthy and slugger Larry Sheets entrenched as Baltimore’s left-handed designated hitter, the best big league opportunity for Traber in 1987 was in the outfield, though both general manager Hank Peters and new skipper Cal Ripken, Sr. preferred fleeter outfielders. “[Bench coach] Frank Robinson has helped me a lot in the outfield,” Traber said that spring. “Playing out there is so instinctual that there’s not a lot you can learn, but he’s taught me how to play certain hitters, how to get in position to make plays.”16

Traber was not happy when the Orioles sent him back to Rochester to work on his outfield defense. “I went down there and felt sorry for myself for two months,” he admitted.17 He raised his average to .274 by season’s end, led the Red Wings in homers and RBIs, and impressed his manager, John Hart, with his improvement on defense. “If you’re talking about playing outfield for the St. Louis Cardinals, Jim couldn’t do that. He can’t cover that kind of ground and speed is always going to be a problem,” Hart acknowledged. “But he has good instincts and gets rid of the ball. I think he can play.”18

After breaking a finger diving back to first base in late August, Traber didn’t join the Orioles in September. Over the winter, however, he went on a diet, hired a conditioning coach and lost 20 pounds through a weightlifting and running regimen.19 He made Baltimore’s Opening Day roster in 1988, but nearly got sent down after only two at bats when the team signed Tito Landrum, a better defender, as a free agent. An injury to another player kept Traber on the roster for another couple of weeks, but he misplayed a couple balls in left field during one of his two starts and was demoted by the 0-18 Orioles (whose streak of futility would reach 0-21) before April was over. At the time, he had one hit in just 11 at bats. “This isn’t what I consider a chance,” Traber complained.20

“A lot of people think I’m cocky, but it’s just that I love to go out there and hit,” Traber once said.21 “Is he cocky? No not really,” Weaver had opined during Traber’s rookie season. “He just acts like a guy who belongs in the big leagues.”22 Humbled by spending part of a fourth straight season at Rochester, Traber took heart from Orioles’ GM Roland Hemond’s promise that he’d return to the majors if he performed. Traber hit his way back to Baltimore by the first week of June and quipped, “I just hope I can stay for more than a week this time.”23 He delivered four three-hit games his first month and remained in the big leagues the rest of the year. “He might not be as good as he thinks he is, but maybe he’s better than we thought,” remarked Robinson, who had replaced Ripken as the Orioles’ manager in April.24

On July 19, both Traber and his former Oklahoma State teammate Tettleton homered against Jerry Reuss in Baltimore’s win over the White Sox, one of few highlights in a season in which the Orioles finished 54-107. Traber managed only a .222 average in 103 games and was duped by the hidden ball trick on Labor Day by Boston’s Marty Barrett. On the final weekend of the season in Toronto, Traber’s pinch-hit, bloop single with two outs in the ninth broke up a no-hit bid by the Blue Jays’ Dave Stieb, the second consecutive start in which the Toronto right-hander had come within one out of a no-hitter.

Foreshadowing his future, Traber was one of 14 finalists for the weekend sports anchor position on Baltimore’s WJZ-TV that off-season. His on-field prospects brightened in December when the Orioles traded Los Angeles native Eddie Murray to his hometown Dodgers after 12 seasons. On April 3, 1989, Traber was Baltimore’s Opening Day first baseman, lining a single in three at bats versus Boston’s Roger Clemens at Memorial Stadium. He platooned with fellow 27-year-old Randy Milligan, an off-season acquisition who’d received few opportunities from two previous organizations despite a .408 minor league on-base percentage.

After Traber started slowly, Robinson tried Milligan full-time and the “Moose” seized the primary starting job for four seasons. The surprising Orioles contended for a division title until the final weekend of the 1989 season, but Traber didn’t contribute much other than a game-winning, pinch-hit homer on June 22. After the All-Star break, he batted only .132 in 76 at bats.

When the Osaka Kintetsu Buffaloes of the Japan Pacific League offered Traber more than $300,000 to play for them in 1990, it was more than triple the peak salary he had earned in Baltimore.25 The Orioles agreed to grant him his release and sold his contract to the Buffaloes.26 To prepare, both Traber and his wife read Robert Whiting’s You Gotta Have Wa about American players adjusting to Japanese baseball, and their experience was positive and enjoyable once they arrived.27

The Buffaloes had a solid team led by 21-year-old Hideo Nomo, who went 18-8 in his rookie season. Another future major leaguer, Masato Yoshii, was the bullpen ace, and former Dodgers’ castoff Ralph Bryant led the club in home runs. Traber intended to play every day and prove he could still hit. He succeeded on both counts, batting .303 with 24 homers and 92 RBIs. He’d grown a beard, dyed his hair blonde and donned an earring, and fans took to him as he rode public trains to the ballpark. “I felt like a Cal Ripken-type person,” Traber said. “It felt like my high school or college days. It was good for your ego.”28

Traber agreed to return to the Buffaloes in 1991 when they offered him a $150,000 raise.29 His signature moment in Japan occurred that May when he chased 5’9”, 160-pound Lotte Orions’ southpaw Kazumi Sonokawa into center field after being hit by a pitch. Orions’ manager, Japanese Hall of Famer Masaichi Kaneda, kicked Traber in the face during the bench-clearing melee, and Traber tripped and fell trying to get at him after straight-arming the Orions’ catcher. “I hit like seven home runs against that team the rest of the year, and every time I’d hit a home run, I’d round third and I would stop and I would walk home and I’d look at the manager and say words to him in Japanese that I kind of found along the way,” Traber said.30

When a rare stomach disorder caused Traber to lose 22 pounds that summer, he feuded with the Buffaloes’ management when they initially resisted letting him travel to the United States to be diagnosed by his doctor brother. Once he recovered, Traber boosted his home run total to 29 and matched Orestes Destrade for the Pacific League RBI lead with 92. Aware that his ex-Orioles’ teammate (and fellow former Big Eight quarterback) Phil Bradley had earned $2 million from the Yomiuri Giants in 1991, The Whammer demanded a raise to $1 million. When the Buffaloes refused, Traber’s Japanese baseball career was over.31

The Cleveland Indians invited Traber to spring training in 1992. Cleveland president Hank Peters and GM John Hart had both come from the Orioles organization, and a solid spring training would give the 30-year-old Traber a chance to be at first base when the Indians visited Baltimore for the inaugural regular-season game at Oriole Park at Camden Yards that April. But Traber developed gout, spent part of the Grapefruit League season on crutches and struggled. His fate was sealed when the Indians traded for first baseman Paul Sorrento nine days before Opening Day.

Traber’s returned to Oklahoma State intending to finish his college degree, and the university inducted him into its inaugural Cowboy Baseball Hall of Fame that year. While there, Traber met with John Fox, the owner of Oklahoma radio station WWLS. “A half-hour later, I was on the radio,”32 Traber said, describing his debut as a sports talk show host. “Back when I was with the Orioles and Tim Kurkjian and Ken Rosenthal and Richard Justice, they would always say to me, ‘Man, when you’re done, you should go into this business. You can really talk’,” Traber recalled.33

Baseball was not out of his blood, however, so Traber signed on with the Sultanes de Monterrey of the Mexican League in 1993. The club was affiliated with the California Angels. “I was tearing Mexico to shreds and they never ever brought me back up,” Traber recalled. “I said I am done with baseball.”34

Traber and his wife had a second son, Beau, who — like his older brother Trabes—would grow up to play college football but their “very bad marriage”35 — like his baseball career — was ending. He went back to WWLS and used his brash, opinionated, unapologetic style to become a top-rated sports talk personality. Nicknamed “the ultimate sports mind” — later shortened to “The Ultimate” — Traber famously dubs callers that he doesn’t agree with “yardbirds”. “When I explode on callers, I think it’s good radio,” he opined.36

A few years after his divorce, Traber married Julie Dailey and became a stepdad to her daughters Courtney, Chelsea and Katelyn. “She’s grounded me beyond belief,” Traber says of his second wife.37

Traber was a regional analyst for the Arizona Diamondbacks when they dethroned the New York Yankees in 2001. “When I was standing on the field, Game Seven of the World Series with the Arizona Diamondbacks, talking with [former Orioles’ teammate] Curt Schilling, that was the only time I missed baseball,” he insisted.38

In 2014, Traber said that a sermon he’d heard a few years earlier had changed his perspective. “God puts you in a place, and there’ a reason he puts you there,” he remembered the pastor saying. “Stop thinking there are better things. I really took that to heart.”39 When he considered his job, co-workers, grandkids and daughters, he said, “I feel really good about my life right now. If I do this to the day I die, I’ll be fine.”40

That day almost came too soon. On May 25, 2019, Traber collapsed at a poker tournament at WinStar World Casino and Resort in Thackerville, OK. People feared he was having a heart attack, stroke or seizure, and his wife drove 140 miles to be with him. “At least she knew I wasn’t dead,” Traber said. “A lot of other people got text messages saying I’d died.”41

A benign tumor was discovered and Traber underwent four hours of brain surgery. “They put my head in a vise, I couldn’t move,” he said. “I had 24 staples in my head. It was serious.”42 Miraculously, “The Ultimate” was back on the air three weeks later. “I love doing radio,” Traber said. “They let me say whatever the heck I want to say.”43

Last revised: October 8, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, www.retrosheet.org and the United States Census from 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930 and 1940.

Notes

1 Zita Arocha, “Newest Oriole a Big Hit in Columbia,” Washington Post, August 1, 1986: B1.

2 Arocha,

3 “17 Prep Stars Sign with Pokes,” Garden City (Kansas) Telegram, February 19, 1979:10.

4 Jeff Browne, “Traber Finds Second Audition Tougher,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, March 20, 1987: 6C.

5 Stan Isle, “Mets’ Ojeda Sympathizes with Former Mates,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1986: 8.

6 “Cowboy Baseball Hall of Fame,” https://okstate.com/sports/2015/3/17/GEN_2014010120.aspx, last accessed September 13, 2020.

7 “Baseball Conference Championships,” https://okstate.com/sports/2015/3/17/GEN_2014010119.aspx, last accessed September 13, 2020.

8 Browne. “Traber Finds . . .”

9 “Wichita State Pummels Oklahoma St.,” Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), June 10, 1982: 59.

10 U.S. Baseball Questionnaires.

11 “Orioles Turn Back Rangers, 4-3,” Plano (Texas) Star-Courier, July 29, 1986: 7.

12 Jim Henneman, “Traber Turns on Hometowners,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1986: 21.

13 Zita Arocha, “Newest Oriole a Big Hit in Columbia.”

14 Browne.

15 Richard Justice, “Trabes Traber’s Dad Determined to Stick with Orioles,” Washington Post, March 2, 1988: D1.

16 Jeff Browne, “Traber Finds Second Audition Tougher.”.

17 Justice, “Trabes Traber’s Dad . . ..”

18 Justice.

19 Justice.

20 “A.L. East Notebook,” The Sporting News, May 9,1988: 15.

21 Henneman, “Traber Turns on Hometowners.”

22 Henneman,

23 Jim Henneman, “Traber Saga, Take Three,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1988: 18.

24 Henneman, “Traber Saga, Take Three.”

25 Bill Glauber, “Traber Thrives in Foreign World; Japanese Baseball Suits Former Oriole,” Baltimore Sun, December 24, 1990: 1D.

26 Richard Justice, “Traber’s Contract Sold to Japan Team,” Washington Post, December 1, 1989: C2.

27 Ken Rosenthal, “Traber Finds Comfort a Long Way from Home,” Los Angeles Times, April 19, 1990: 8.

28 Glauber, “Traber Thrives . . .”.

29 Glauber.

30 “Jim Traber Tells Story of Infamous Japanese Baseball Brawl,” Oklahoma’s Own www.news9.com, October 10, 2019, https://www.news9.com/story/5e35d0975c62141fdee95495/jim-traber-tells-story-of-infamous-japanese-baseball-brawl (last accessed September 22, 2020)

31 Ken Rosenthal, “Only Chopped Stick Traber Wants to See is Broken Indian Bat,” Baltimore Sun, February 3, 1992: D1.

32 Berry Tramel, “Collected Wisdom: Jim Traber Says, ‘When I Explode on Callers It’s Good Radio,” https://oklahoman.com/article/5357947/collected-wisdom-jim-traber-says-when-i-explode-on-callers-its-good-radio, October 18, 2014, last accessed September 13, 2020.

33 Tramel.

34 Tramel.

35 Tramel.

36 Tramel.

37 Tramel.

38 Tramel.

39 Tramel.

40 Tramel.

41 Bill Haisten, “’Incredibly Blessed’ Jim Traber is Back to His Irascible Self After Seizure and Brain Surgery,” https://tulsaworld.com/sports/bill-haisten-incredibly-blessed-jim-traber-is-back-to-his-irascible-self-after-seizure-and/article_6d756dfd-632b-53b8-b359-6ac00bc36ecc.html, July 14, 2019, last accessed September 13, 2020.

42 Haisten.

43 “Outspoken Jim Traber Discusses the Ultimate Health Scare,” www.News9.com, October 10, 2019, https://www.news9.com/story/5e35d0825c62141fdee9544a/outspoken-jim-traber-discusses-the-ultimate-health-scare (last accessed September 22, 2020).

Full Name

James Joseph Traber

Born

December 26, 1961 at Columbus, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.