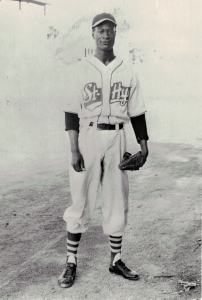

Connie Johnson

“He would come in and relieve Satchel, and when they put Johnson out there, we thought we’d have it easy then. And he would come in and throw harder than Satchel did! Just like jumpin’ from the frying pan into the fire.” – Warren Peace, Newark Eagles1

“He would come in and relieve Satchel, and when they put Johnson out there, we thought we’d have it easy then. And he would come in and throw harder than Satchel did! Just like jumpin’ from the frying pan into the fire.” – Warren Peace, Newark Eagles1

Connie Johnson made his White major-league debut with the Chicago White Sox on April 17, 1953, pitching the final two innings against the St. Louis Browns. He entered the game with his team behind 6-4 and pitched two scoreless innings. Only the remnants of the 972 spectators who had braved the cold of a Chicago afternoon in April were in the stands as Johnson became the first Black man to pitch for the White Sox. In the top of the ninth, with one out, Satchel Paige came to bat for the Browns. The ageless one had entered the game in the seventh inning. When Johnson took the mound in the eighth inning, it was the first time two Black pitchers had opposed each other in an American League game.

Clifford Johnson Jr. was born on December 27, 1922, in Stone Mountain, Georgia, a town about 15 miles east of Atlanta. He was the second of three sons born to Clifford and Rosa Allen Johnson. His older brother, Jack, was born in 1911, and his younger brother, Victor, was two years younger than Clifford. His father was a paving cutter at a granite quarry. The senior Johnson lived almost his whole life in Stone Mountain and died in 1961.

The Johnson family moved to Atlanta when Clifford was about 5 years old, and he attended school there until the family moved back to Stone Mountain a few years later. He attended Stone Mountain Elementary School and completed one year of high school, his formal education ending in 1938 when he went to work with his father at the granite quarry. He saw his first professional game, between the Toledo Crawfords and Kansas City Monarchs, at Ponce de Leon (Poncey) Park in Atlanta in June 1940.

The next day, as Johnson told the Baltimore Afro-American in 1956, “I went to work with my dad up in the mountains. A big limousine (it was a LaSalle) came by.” Jesse Owens and a Stone Mountain neighbor, James “Joe” Greene, were in the car. Greene was a catcher with the Kansas City Monarchs, and Owens was a part-owner of the Crawfords. “Greene had told Owens that I could throw hard. So Owens asked me to pitch for (the Crawfords). I told him I couldn’t, but he told me to try and my dad said to go ahead. So I got my spikes and glove and went along.”2 In the second game in Atlanta between the Crawfords and the Monarchs, Johnson, in a uniform two sizes too large, excelled.3 After the game, he was asked to travel with the Crawfords; team manager Oscar Charleston assured his mother that he would watch out for the young pitcher.

Johnson first played with the Crawfords (formerly of Pittsburgh but by then splitting their time between Toledo and Indianapolis) in 1940, joining them shortly after being recruited by Owens. He made his debut in Indianapolis on June 28, 1940, appearing in place of John Wright against the Kansas City Monarchs. He pitched all nine innings as the Crawfords came from behind to win, 5-4. In the winning eighth-inning rally, the key hits were a run-scoring double by Willie Spencer and a single by Jimmy Johnson.4 In his very first season, at the tender age of 17, Cliff Johnson was selected to play for the West All-Stars in the annual East-West Game. He entered the game with one out in the sixth inning and his team trailing 8-0. He had come on in relief of Walter “Lefty” Calhoun, who had been ineffective. There were runners on first and second. Johnson was quickly faced with a bases-loaded situation when he failed to cover first base on a groundball to the right side of the infield. He then settled down and pitched the final two outs of the sixth inning, striking out Marvin Barker and retiring Bill Perkins on a foul popup to the catcher. No runs scored on his watch. After he left the game, the East padded its lead with another three runs and won the game 11-0.5

“The night no one would warm me up. They say I was throwing too hard. I had a week rest. I walk the first three men – three balls on the other one. They got one hit and I struck out 22.” – Connie Johnson, remembering a game against the Chicago American Giants in 1941.6

The Crawfords folded after the 1940 season, and Johnson spent the next two seasons with the Kansas City Monarchs. The Monarchs played in towns big and small and Johnson, like most of his teammates, played in the shadow of Satchel Paige. Johnson got his chances, though, and one of his impressive early outings with the Monarchs was a 2-0, four-hit win over the Chicago American Giants on August 19, 1941, at Perry Stadium in Indianapolis.7

During a spring-training game on April 16, 1942, in Port Arthur, Texas, Johnson pitched two scoreless innings in a 19-9 win over the Cleveland Buckeyes.8 Over the course of the season, he had more opportunities to shine.

On June 21, 1942, at Ruppert Stadium in Kansas City, it was Elks Day with about 3,500 members of Black Elks lodges attending from an eight-state Midwest Association region meeting. The total attendance was around 5,000. Findley Wilson of Washington, the Elks grand exalted ruler, threw out the first pitch for the 3:00 P.M. start. With the score tied at 4-4, Johnson was brought in to pitch with two outs in the fifth inning and surrendered the lead. He then pitched scoreless ball through the ninth inning. The score was 5-4 after 8½ innings. In the bottom of the ninth, Monarchs catcher Joe Greene hit a home run over the center-field scoreboard to tie the game. Buck O’Neil singled over second base, then advanced to second and third on back-to-back infield outs. Johnson was due up, but manager Frank Duncan had another pitcher – Hilton Smith – pinch-hit for him. On a 2-and-2 count, Smith singled to right field. Johnson was credited with the win and Memphis Red Sox lefty Verdell Mathis bore the complete-game loss.9

Paige was the drawing card for the June 24 game in Rochester, New York, against the semipro Eber-Seagrams team. The Monarchs won, 6-1, as 4,500 fans saw Paige throw one-hit ball and walk two in his five innings. Veteran White major-league right-hander Ted Kleinhans was “imported from Syracuse for the occasion” to pitch for Eber-Seagram.10 The team was the three-time Western New York semipro champion.11 Kleinhans struck out 11 Monarchs, two more than Paige, though Paige got to him for a double and a run batted in. Three errors (one committed by Kleinhans) and a wild pitch helped the Monarchs add two runs in the fifth and three runs in the sixth. In the three-run sixth, O’Neil tripled, Paige singled him in, and Bonnie Serrell singled. Kleinhans threw away the ball on a bunt he fielded, and a fly ball scored the last of the Monarchs’ runs. Johnson pitched the last four innings, allowing just one hit, a ninth-inning homer.

On July 2 the Monarchs faced the Chicago American Giants in a doubleheader at Ruppert Stadium. Johnson entered the second game with two out in the sixth inning. The Giants had rallied to tie the game at 6-6 and Johnson was able to stop the damage. In the bottom of the inning, the Monarchs retook the lead, 7-6, and Johnson pitched a scoreless seventh inning for the win.12

Two days later, after a bus trip of 450 miles on back roads, the Monarchs were in Memphis to play the Red Sox in a July 4 doubleheader. Memphis had been on a tear, winning 15 straight games, and they won the first game of the doubleheader to make it 16 in a row. Johnson pitched the seven-inning second game and was able to win the game for the Monarchs, scattering eight hits.13

In St. Joseph, Missouri, on July 16, 1942, the Monarchs played Memphis in front of 1,900 fans, the largest turnout of the season in St. Joseph. Johnson came on in relief with one out in the eighth inning and the game tied, 3-3, pitched flawlessly, and drove in the winning run with a triple. He tried to stretch the triple into an inside-the-park homer but was out at the plate on a perfect relay throw.14 In Scranton, Pennsylvania, on July 31, 1942, Johnson took the mound against the Philadelphia Stars and won, 7-4. The crowd of 2,361 was disappointed that Paige made only a token appearance, relieving Johnson in the eighth inning, and pitching the last two innings.15

Johnson was back in St. Joseph on August 24 and got the start against the Chicago American Giants. He struck out 11 batters and scattered nine hits in winning the game, 10-4, in front of a record crowd of 2,400. The Monarchs had 14 hits in the game, including a home run by Serrell and a pair of doubles by Ted Strong.16

It was in 1942, by Johnson’s own account, that he was first called Connie. Johnson’s favorite song was “Basin Street Blues,” sung by Connie Boswell with Bing Crosby. Johnson would sing it himself and took to calling other folks Connie (including fellow pitchers Satchel Paige and Hilton Smith), or so the story goes. Eventually, his teammates started to call him Connie.17

The fact that Negro League statistics are incomplete is well-known, but according to several articles, one of which appeared in the Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), Johnson led the Negro American League in strikeouts in 1942.18 In the 1942 Negro League World Series, the Monarchs swept the Homestead Grays, but Johnson saw no action as manager Frank Duncan used only three pitchers – Paige, Smith, and Jack Matchett – in the four games.

Johnson entered the Army on January 26, 1943, and spent the next three seasons away from the Monarchs. He was honorably discharged on February 5, 1946.

He returned to the Monarchs in 1946 and was undefeated through June. On Opening Day he relieved Hilton Smith in the eighth inning and pitched the final two innings as the Monarchs defeated Memphis, 3-0. In his two innings, he struck out four batters and allowed only one hit. His first win of the season came against the House of David on May 27. Smith had started and was ineffective. Johnson came on in the fourth inning with his team trailing and struck out seven batters in three innings. The Monarchs came from behind and took the lead in the fifth inning, making him the pitcher of record.

Johnson excelled in a game at Dexter Park in Queens, New York, on July 12, throwing a two-hitter as the Monarchs defeated the Brooklyn Bushwicks, 3-0; he struck out the side in each of the first two innings.19 Johnson won eight of 10 decisions, had 95 strikeouts in 86 innings, and was scheduled to appear in the East-West Game in Washington on August 15.20 However, he appeared in neither the game in Washington nor the East-West Game in Chicago on August 24. He did receive the George Stovey Award, given to the top pitcher in the Negro Leagues.

Johnson was absent from the East-West games because he had injured his arm. During the offseason he went to a chiropractor in Laredo, Texas, and, upon the recommendation of manager Buck O’Neil, began a running regimen. When he returned to the Monarchs in 1947, his blazing speed was gone, but he had better control of his pitches.

Johnson’s last year with the Kansas City Monarchs was 1950. On June 11, 1950, in a doubleheader at Blues Stadium in Kansas City between the Monarchs and the Indianapolis Clowns, the crowd of 9,165 had an opportunity to see that the future of Black baseball would be not in the Negro Leagues but in White Organized Baseball. Johnson won his sixth game of the season in the nightcap, 3-1, as he limited the Clowns to five hits, only three after the first inning. In the fourth inning, O’Neil singled and the team’s young left fielder, Elston Howard, homered for the decisive runs. In the opener that day, also won by the Monarchs, 5-1, the Clowns scored their only run of the game on a throwing error by Monarchs shortstop Ernie Banks. Both Howard and Banks had RBI singles during a five-run eighth inning in the opener.21 Each went on to White major-league stardom and All-Star recognition and was named his league’s Most Valuable Player.

For his part, Johnson was named to the West All-Star team for the annual East-West Game on August 20, 1950. He entered the game in the fourth inning with the West leading, 2-1. After giving up a game-tying run in his first inning, he settled down and was the beneficiary of three fifth-inning runs. He came out of the game after the sixth inning with his team leading 5-2. The East managed only one run in the seventh inning off Bill Powell, and Johnson was credited with the 5-3 win.

After finishing the 1950 Negro American League season with an 11-1 record,22 Johnson barnstormed with Satchel Paige. One of the stops was at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, and Johnson pitched in relief of Paige on October 15. He gave up four runs, three on a homer by Del Crandall, in four innings.23

Before the 1951 season, the Monarchs sold Johnson’s contract to St. Hyacinthe in the Class-C Quebec Provincial League. The team finished in fifth place with a 55-67 record. Johnson led his team’s pitchers with 15 wins (against 14 losses), and his 172 strikeouts paced the league.

In 1952, on the recommendation of scout John Donaldson, Johnson’s contract was purchased by the Chicago White Sox and he was assigned to Colorado Springs in the Class-A Western League. At the time there were still relatively few Black players in the minor leagues and one display of verbal abuse was particularly disturbing. The offenders were the Omaha Cardinals and their manager, George Kissell. After a game on July 18, Colorado Springs club officials in a telegram to league officials, said, “This club does not feel there is a place in the Western League or in baseball for discriminatory remarks directed against our players nor for profanity directed toward our fans, not for general poor sportsmanship.”24 Kissell denied the allegations.

Johnson’s pitching in 1952 was noteworthy. The 6-foot-4, 200-pound right-hander set the Western League season strikeout record with 233 in 248 innings, surpassing the 212 strikeouts by Bobby Shantz in 1948. Johnson finished the season with an 18-9 record.

The blazing fastball that had keyed his success in his early days in the Negro Leagues was a bit slower by then due to the arm problems that dated back to 1946. In 1952 he said, “I found out later that I’d been pitching too often and not warming up enough. I relied mostly on curves at first, but lately I’m getting more confidence back in my fast ball. I’ll throw either one in the clutch now.”25 On June 11 he tied the Western League record for strikeouts in a game when he fanned 17 in a 13-inning, 8-5 win over the Pueblo Dodgers.26

Johnson joined the White Sox in 1953, becoming the 31st player of color to join the White major leagues, although he was only the seventh Black pitcher. Among his teammates was Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso, against whom he had pitched in the Negro Leagues.

Although the big leagues had initiated integration in 1947, acceptance of that fact was not universal as Johnson discovered during spring training in 1953. When the White Sox headed north, neither he nor Miñoso was allowed to play when the team traveled to Memphis to face the Philadelphia Athletics.27

Johnson’s first start for the White Sox came on April 28 against the Washington Senators. He came out of the game with one out and two on in the fourth inning. Although he had a 5-1 lead, he had walked four and got the early hook.

When the time came to cut the rosters to 25 players, Johnson was optioned to Charleston, West Virginia, in the Triple-A American Association. His record was 0-1 when he was sent down and he had a 6-6 record in 15 appearances (14 starts) with Charleston.

Johnson was recalled by the White Sox on July 29. He earned his first big-league win on August 1 when he shut out the Senators, 4-0, striking out 10 batters. The win brought the White Sox to within 4½ games of the league-leading New York Yankees. On August 7 Johnson started the opener of a four-game series at Yankee Stadium against New York’s Eddie Lopat. The Yankees, with an inside-the-park homer by Mickey Mantle followed by a homer by Yogi Berra, took a 4-1 lead in the third inning. Johnson lost the game, and his record fell to 1-2. For the season, he was 4-4 for the White Sox, posting an ERA of 3.56.

During his time with the White Sox, Johnson recommended one of his Monarchs teammates to manager Paul Richards. The White Sox front office did not follow up on the tip, and Ernie Banks wound up signing with the Cubs.

After the season, Johnson barnstormed with the Roy Campanella All-Stars and defeated a team made up of Pacific Coast League players, 8-5, at Seals Stadium in San Francisco.28

He pitched the entire 1954 season with the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League, going 17-8 with 145 strikeouts. His batterymate that season was former Monarchs teammate Elston Howard. Johnson began 1955 with Toronto and, in early July, after posting a 12-2 record with a 3.05 ERA in Triple A, was called up to the White Sox once more.

Johnson’s deliberate style confounded batters as he went 7-4 with a 3.45 ERA in 1955. In his first game back with the White Sox, on July 4 in the first game of a doubleheader, he defeated the Kansas City Athletics, 8-3, at Kansas City, pitching a complete game. The occasion marked his first game back in Kansas City since his days in the Negro Leagues. His second win was a 6-0 whitewashing of the Cleveland Indians in which he struck out 12 batters.

The White Sox were in an exciting pennant race with five teams within 5½ games of one another. On July 28 Johnson edged New York, 3-2, to put the White Sox into a first-place tie with the Yankees. His next start, at Boston, attracted a monster crowd of 35,455 to Fenway Park for the matchup between the first-place White Sox (62-39) and the third-place Red Sox (60-43). Johnson prevailed over Tom Brewer of the Red Sox, 2-1, to bring his record to 4-1 and he lowered his ERA to 2.25. After August 21 Johnson tailed off, going 1-3 in his last five starts. The White Sox were in first place as late as September 3, but they lost 12 of their last 23 games to finish in third place, five games behind New York.

After the season, Johnson barnstormed with the Willie Mays–Don Newcombe All-Stars. On October 15 he pitched a one-hitter as the All-Stars defeated a group of American League players 2-0 at Columbus, Mississippi, in front of 1,617 spectators.29

Johnson’s pitching woes at the end of the 1955 season continued in the early part of 1956. In his first five appearances, he was 0-1 with a 3.65 ERA. He had control problems in each of his two starts, walking seven batters in seven innings. In the second start, on May 10 at Boston, he was pulled from the game in the first inning after loading the bases and allowing the Red Sox to tie the game at 1-1. The 33-year-old pitcher was put on the trading block.

On May 21, 1956, in a six-player deal, Johnson, George Kell, Bob Nieman, and Mike Fornieles were sent to Baltimore for Jim Wilson and Dave Philley. Not long after the trade, Johnson faced his old mates and won a 3-2 verdict on June 1, allowing five hits.

Johnson brought his family with him to Baltimore. He had met his wife, Harion Orita Caver, in Kansas City in 1947 and they were married on September 28, 1953. By 1956, there were two children: Daughter Denise was born in 1954 and son Clifford was born a year later. They later welcomed another son, Kevin. The family’s home base remained Kansas City. Harion, who worked at the Betty Rose Coats and Suit Company, died on December 21, 1971, at the youthful age of 47.30

In Baltimore, Johnson was reunited with Paul Richards, who, through the proverbial grapevine, had heard that Johnson had been tipping off his curveball while with the White Sox. Richards worked with Johnson to make the necessary change in his motion. Although his 9-11 record in 1956 hardly placed him among the league leaders, his manager had great praise for Johnson. After Johnson defeated the Indians, 4-1, in Cleveland on September 13, Richards proclaimed, “He’s the best right-hander in the league.”31

Johnson’s losing record reflected the fact that he pitched in bad luck in 1956. On June 21 he was matched up against Chicago’s Jack Harshman. The only run of the game was scored by the White Sox in the first inning. Jim Rivera walked, stole second, and scored on a double by Nellie Fox. Johnson then hurled hitless ball until he was pulled for a pinch-hitter in the top of the eighth inning. Harshman, like Johnson, yielded only one hit, a seventh-inning double by Gus Triandos, as the White Sox won, 1-0.

On August 14 Johnson recorded his first shutout with Baltimore, a six-hit, 11-strikeout gem. He followed it with a 3-2 complete-game win against the Yankees. The back-to-back wins brought his season’s record to 6-7 and set the stage for a night in his honor held at Memorial Stadium on August 28.32

On September 23 in Baltimore, Johnson shut out Washington, 6-0, on three hits. The win assured the Orioles of a sixth-place finish, their best result since moving to Baltimore from St. Louis in 1954, and the best season record for the franchise since 1945.

Of his success in 1956 as opposed to his problems at the end of the 1955 season with the White Sox, Johnson said, “They don’t read me the way they used to. I didn’t hide my grip of the ball very well in previous years and coaches on opposing teams were reading me like a book. Now I cover the right hand up with my glove. I’m also throwing the slider better than I used to.”33

For the season he went 9-10 with the Orioles (9-11 overall). He had two shutouts and his ERA was 3.44. In five of his losses, he allowed three or fewer runs. He led the Orioles staff in ERA (3.43), shutouts (2), and strikeouts (130), and tied for the team lead with nine complete games.

In 1957 Johnson won 14 games against 11 losses for the Orioles. He tied with Bob Turley for the most wins by an Orioles pitcher since the team moved to Baltimore. Three of Johnson’s wins were shutouts. The first was a 2-0 two-hitter against Kansas City on May 20. He struck out four batters, walked one, and set down the A’s one-two-three in seven of nine innings.

Johnson’s 1-0 blanking of the Kansas City Athletics on June 26 was the third of four consecutive shutouts by Orioles pitchers, tying an American League record. The others were thrown by Hal “Skinny” Brown, Billy Loes, and Ray Moore. Johnson in his shutout allowed only three hits, struck out four, walked none, threw 86 pitches, and finished the game in a tidy 1:45. Jim Busby provided all the offense needed with a fifth-inning home run.34

Johnson struck out 10 or more batters five times in 1957. He tied the Orioles team record of 14, initially set by Turley on April 21, 1954, in a 6-1 win over the Yankees on September 2 in the second game of a doubleheader at Memorial Stadium. The 14 strikeouts were the most in a game by an American League pitcher in 1957. Speaking of this performance, the ever-understated Johnson said, “It was awful close and hot out there, and I was sweating a powerful lot. I felt strong, but kind of mushy-like.” The room erupted in laughter.35 Johnson was not much into discussing his pitching ability. As writer Lou Hatter said, “Getting Johnson, a baseball disciple of Satchel Paige, to talk about his mound skills is like trying to extract a wisdom tooth from a full-grown Georgia alligator. Not really hazardous; it simply isn’t done.”36

Johnson’s 14 wins set the American League record at the time for wins by a Black pitcher. Satchel Paige had gone 12-10 for the St. Louis Browns in 1952. Jim “Mudcat” Grant raised the bar with 15 wins in 1961. Johnson was third in the league in strikeouts (177), and he had the best strikeout-to-walk ratio (2.68) of the league’s starters.

Despite Johnson’s pitching acumen and the team’s record shutout streak, the 1957 Orioles were not contenders. After the four shutouts, their record stood at 32-34, and they wound up the season in fifth place with a 76-76 record, 21 games behind the pennant-winning Yankees.

Johnson slipped to 6-9 with a 3.88 ERA in 1958. The season did not start at well, but eventually he found his rhythm and won three consecutive starts from August 11 through August 22 that brought his record up to 6-7 and his ERA down to 3.19. However, his 35-year-old arm betrayed him, and he went 0-2 with a 10.64 ERA in the last three appearances of his big-league career.

Johnson began the 1959 season at spring training with the Orioles. His best outing of the spring came on April 1 against the Pittsburgh Pirates in Miami. He entered the game in the top of the ninth inning with the score tied, 3-3, and pitched four hitless innings. Johnson received credit for the win when the Orioles scored the decisive run on a single by Al Pilarcik in the bottom of the 12th.37 In his final outing of the spring, he allowed three runs and six hits to the Cardinals on April 5.38

Although Johnson’s career was nearing its end, there was still time for a bit of levity. At that point, the Orioles had a pitching phenom by the name of Steve Dalkowski whose wildness was the stuff of legend. Wrote David Condon in the Chicago Tribune, “The day the 21-year-old southpaw was scheduled to pitch bunting practice for pitchers, Connie Johnson stepped up to the plate attired in shin guards, a chest protector, and a mask, clutching a bat in one hand and a list of his next of kin in the other.”39

Johnson did not break training camp with the Orioles, who were in the midst of a youth movement. On April 9, 1959, after boarding the team bus for the presidential opener in Washington, Johnson was informed that he was being was sent to Vancouver of the Pacific Coast League.40 “The Tall Statuesque Great Stone Face from Stone Mountain, Georgia,” as Lou Hatter of the Baltimore Sun depicted Connie Johnson, finished his time in the majors with a record of 40-39 with an ERA of 3.44. The blazing fastball that had so impressed Jesse Owens 19 years earlier was no longer in evidence and Johnson’s flirtation with greatness in 1957 could not be replicated.

Although he went 8-4 with a 3.16 ERA at Vancouver in 1959, there was no late-season call-up. Johnson did not return to the major leagues. In a relief effort on August 8, 1959, he had been credited with his last win in White Organized Baseball. The Mounties finished second to Salt Lake City in the PCL.

In 1960 Johnson was back with Vancouver, but it was apparent early on that he would not be there long. In his only appearance, on April 16, he gave up three runs and six hits in 2⅔ innings and was charged with the loss as Sacramento defeated Vancouver, 5-1.41 A week later, he was released.

The following season Johnson was still pitching, but his career had come full circle. He was barnstorming with the Philadelphia Stars of the Negro American League, back in the league where he started his career as a teenager.42

Johnson’s time in the major leagues lasted less than four full seasons. Based on the rules in place when he finished his big-league career in 1958, he was not entitled to a pension. However, in 1997, Major League Baseball awarded annual pensions of $10,000 to a group of about 90 Black ballplayers, including Johnson, whose combined service in the Negro Leagues and the White Majors totaled four or more years.43

After baseball, Johnson went to work as an inspector for the Ford Motor Company in Claycomo, Missouri, staying with them until he reached retirement age in 1985.

Johnson served as an honorary pallbearer at the funeral of Satchel Paige on June 12, 1982.

He was an active supporter of the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, and was among a number of Negro League ballplayers who shared their experiences with students in the Kansas City public schools.

In 1994, on the eve of the airing of Ken Burns’ series, Baseball, Johnson was among several veterans of the Negro Leagues who appeared at a picnic at the White House.44

Clifford “Connie” Johnson died on November 28, 2004, in Kansas City and was buried at Leavenworth National Cemetery.

“Connie was a good pitcher in the major leagues, but he was a great pitcher in the Negro Leagues. No comparison. He threw hard for the Monarchs. Hard. He had good control. Could have won 20 games in the big leagues. Oh yeah. Could have won 20 games every year. That’s Connie Johnson.” – Connie Johnson’s Kansas City Monarchs teammate and manager Buck O’Neil.45

Acknowledgments

In addition to fact-checker Carl Riechers and copy editor Len Levin, the author is highly indebted to Cassidy Lent at the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Research Center for her assistance in gaining access to Connie Johnson’s file and Hall of Fame questionnaire.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Seamheads.com, Ancestry.com (1930 Federal Census), Johnson’s page on the Negro League Baseball Museum website, and the following:

Bready, James H. Baseball in Baltimore: The First 100 Years (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998)

Hoffman, John C. “Hats Off: Connie Johnson,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1955: 19.

Kelley, Brent. “Connie Johnson Remembers His Pitching Days,” Sports Collector’s Digest, June 15, 1990: 260-263 (Recorded interview is available at SABR.org)

Luke, Bob. Integrating the Orioles: Baseball and Race in Baltimore (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, 2016)

Vanderberg, Bob. “Sox Footnote Provides Rich Anecdote,” Chicago Tribune, September 23, 1990: 2.

Notes

1 Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts of the Period 1924-1960, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishers, 1998), 174.

2 Sam Yette, “’Happy to Pitch for Orioles, Says Connie,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 28, 1956: 13.

3 Tom Hawthorn, “Connie Johnson: 1922-2004: Ace Pitcher Was Too Old to Fully Benefit from Desegregation and Instead Became the Strikeout King on Three Canadian Teams,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), January 25, 2005: S7.

4 “Crawfords Defeat Loop Leaders, 5-4,” Indianapolis Star, June 29, 1940: 19.

5 William G. Nunn, “23,000 See East Maul West, 11-0,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 24, 1940: 16; Art Carter, “East Blanks West 11-0 in Baseball’s Big Classic,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 24, 1940: 19.

6 California League questionnaire completed by Connie Johnson, April 26, 1952.

7 “Kansas City Monarchs Win at Perry Stadium,” Indianapolis Star, August 20, 1941: 19.

8 “Monarchs in 19-9 Victory,” Port Arthur (Texas) News, April 17, 1942: 5.

9 “Game to Monarchs in 9th,” Kansas City Times, June 22, 1942: 12.

10 Paul Pinckney, “Paige Yields 1 Hit in 5 Frames as Monarchs Trip Ebers, 6-1,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), June 25, 1942: 25, 30.

11 “Satchel ‘Born with Control,’: Paige Explains Hurling Feats,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), June 21, 1942: 3C. An advertisement for the game on page 17 of the June 20 Democrat and Chronicle declared of Satchel Paige that “Countless expert(s) and big league players rate him the greatest pitcher of all time.”

12 “Twin Monarch Triumph,” Kansas City Times, July 3, 1942: 13.

13 Sam Brown, “Kansas City and Red Sox Divide Pair,” Chicago Defender, July 11, 1942: 19.

14 “A Close One to Monarchs,” Kansas City Times, July 17, 1942: 13; Biggest Crowd of Year Sees Monarchs Defeat Memphis, “St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, July 17, 1942: 13.

15 Chic Feldman, “Indifferent Paige Hooted by 2,361 Irked Stadium Guests for Brief, Late Appearance,” Scranton Tribune, August 1, 1942: 11.

16 “Record Stadium Crowd Watches Monarchs Win,” St. Joseph Gazette, August 25, 1942: 5.

17 Yette.

18 “Cliff Johnson Leads Monarch Pitching Staff this Season,” Capital Times (Madison, Wisconsin), July 19, 1946: 13.

19 “Monarchs Top Bushwicks, 3-0,” New York Times, July 13, 1946: 19.

20 “West Favored Over East in Dream Game,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 13, 1946: 11.

21 “Monarchs Take Two,” Kansas City Times, June 12, 1950: 13.

22 “League Highlights,” Alabama Citizen (Tuscaloosa, Alabama), September 16, 1950: 7.

23 “Lemon’s All-Stars Nip Paige’s Royals, 7-6,” Los Angeles Times, October 16, 1950: C-4.

24 “Sky Sox Protest Cards’ Conduct: Accuse Kissell, Team, of Abusing Negroes,” Council Bluffs (Iowa) Nonpareil, July 20, 1952: 23.

25 Maury White, “Bruin Bats, Vocal Efforts Fail to Bother Sky Sox Ace,” Des Moines Tribune, June 26, 1952: 36.

26 “Cliff Johnson Ties Western League’s Strikeout Record,” Atlanta Daily World, June 12, 1952: 7.

27 Wendell Smith, “Memphis Bars Minoso as Chisox Play,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 11, 1953: 1, 4.

28 “Campanella Shows Way,” New York Times, October 24, 1953: 20.

29 “Mays-Newk Gates in Dixie Dropping with Temperature,” The Sporting News, October 26, 1955: 23.

30 “Mrs. Clifford Johnson, Jr. Obituary,” Kansas City Times, December 27, 1971: 48.

31 Jim Ellis, “Con Johnson Best in A.L., Chirps Boss,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1956: 17.

32 “Connie Johnson Gets $500, Gifts at the Stadium Tonight,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 28, 1956: 22.

33 Ellis, The Sporting News, September 26, 1956: 17

34 Ellis, “Nieman Ready to Return to Oriole Lineup,” Baltimore Evening Sun, June 27, 1957: 55.

35 Lou Hatter, “Johnson Feeling ‘Mushy’ While Tying S.O. Record,” Baltimore Sun, September 3, 1957: 17, 19.

36 Hatter, September 3, 1957: 17.

37 Jack Hernon, “Orioles Edge Pirates in 12 Innings, 4-3,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 2, 1959: 26.

38 Eddie Storin, “Orioles Defeat Cards Win Grapefruit Title,” Miami Herald, April 6, 1959: C1.

39 David Condon, “In the Wake of the News,” Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1960: F-2.

40 Lou Hatter, “C. Johnson Cut, Hale Retained by Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, April 10, 1959: 23, 26.

41 Merv Peters, “Goss (Plus Pills) Puts Pep in Mounties’ Bats,” Vancouver Sun, April 18, 1960: 10.

42 “Birds Test Philly Stars,” Daily Sentinel (Grand Junction, Colorado), August 4, 1961: 8.

43 Murray Chass, “Pioneer Black Players to be Granted Pensions,” New York Times, January 20, 1997: C9.

44 Donnie Radcliffe, “The White House Pitches In; At Picnic for Ken Burns’ ‘Baseball,’ Hopes Are High for Extra Innings,” Washington Post, September 12, 1994: D-01.

45 Frank Russo, “Clifford “Connie” Johnson, Jr. in “Find a Grave Memorial,” December 1, 2004.

Full Name

Clifford Johnson

Born

December 27, 1922 at Stone Mountain, GA (USA)

Died

November 28, 2004 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.