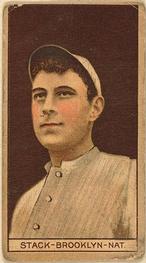

Eddie Stack

Right-handed pitcher Eddie Stack was a collegiate and semipro standout who never played a minor league game but underachieved as a mid-Deadball Era major leaguer. Stack had ample size, a strong arm, and first-rate intellect. His debut in the big leagues in May 1910 was spectacular: a three-hit shutout of a Chicago Cubs team headed for a National League pennant. Thus, Stack’s failure to fulfill his promise puzzled contemporary observers.

Right-handed pitcher Eddie Stack was a collegiate and semipro standout who never played a minor league game but underachieved as a mid-Deadball Era major leaguer. Stack had ample size, a strong arm, and first-rate intellect. His debut in the big leagues in May 1910 was spectacular: a three-hit shutout of a Chicago Cubs team headed for a National League pennant. Thus, Stack’s failure to fulfill his promise puzzled contemporary observers.

Respected sports columnist Hugh Fullerton diagnosed comfortable family circumstance, an easygoing nature, and a lack of ambition as the probable cause of Stack’s mediocrity. “He knows he can quit at any time and his ambition is not stirred by the necessity of making good,” Fullerton observed in early 1912. “Probably had he been a poor boy hustling to make a living, he would have been a star pitcher at once.”1

Whatever the cause, Stack did not meet the expectations of his various ballclub employers and was given his unconditional release in February 1915. Only 27 and in good physical shape, Stack did not attempt to revitalize his career through improvement in the minors. Nor did he seek a berth in the renegade major Federal League. Instead, he contented himself by pitching semipro ball in Chicago while he prepared for his lifelong calling as an inner-city high school teacher and administrator, a vocation that he pursued until only shortly before his death in 1958. The story of Eddie Stack’s life — societally beneficial, if underwhelming in baseball — follows.

William Edward Stack was born in Chicago on October 24, 1887. He was the third of five children2 born to Edward Stack (1853-1908), a prosperous grocer turned city bureaucrat, and his wife Mary Ann (née Mulvihill, 1858-1913). Both were Irish Catholic immigrants from County Kerry. Eddie, as he was always called, was educated in local schools until midway through high school. Lest their teenage son fall into trouble on baleful Chicago streets, his parents then dispatched him to St. Viator College, an all-male prep school/college run by a religious order in Bourbonnais, Illinois, about 50 miles south of the Windy City.

Like many Catholic schools of the day, St. Viator deemed athletics to be a healthy diversion for the young men placed in its charge. It developed into a turn-of-the-century Midwest sports powerhouse, its small enrollment (300 students) notwithstanding. As a prep schooler, Stack, already good-sized and a natural athlete, was a three-sport star: center, tackle, and team captain in football; center and team captain in basketball, and originally a catcher on the baseball team.3 When he matriculated to the college, he was converted into a pitcher and soon became the staff ace. In spring 1908, St. Viator posted an 18-1 record and claimed the co-championship of secondary (or small school) western colleges and universities.4

While still a college undergraduate, Stack began pitching Sunday games for Anson’s Colts in the fast semipro Chicago City League.5 During summer 1908, he hurled weekend contests for another top-flight semipro club, the Joliet (Illinois) Standards. The latter stint became the source of eligibility controversy when team captain Stack returned to St. Viator for his senior year. As a result, he made only three college mound appearances in spring 1909.6 That June, Eddie was awarded his A.B. degree. Thereafter, he focused upon finding a livelihood in pay-for-play baseball.

As he had the year before, Stack pitched for the Joliet Standards in spring 1909, winning six of seven outings, including a pair of two-hit victories over clubs from the Chicago City League.7 After his graduation from St. Viator, however, Eddie abandoned Joliet to pitch for the Logan Squares, a better-paying city league nine operated by former Chicago White Sox pitcher Jimmy Callahan.8 In his Logan Squares debut, Stack shut out the archrival Gunthers, 1-0.9 A week later, he whitewashed the city league leaders, the renowned Leland Giants, outdueling future Hall of Famer Rube Foster, 5-0.10

Days after turning in this masterly performance, Stack became the object of controversy between Chicago’s two major league clubs, with both the White Sox and the Cubs asserting a contractual claim upon the prospect’s services. Believing himself to be a free agent, Stack signed a contract for the upcoming 1910 season with White Sox club boss Charles Comiskey. Meanwhile, Cubs honcho Charles W. Murphy purchased the rights to Stack claimed by Joliet club owner Bill Moran.11 Shortly thereafter, Stack signed a contract to play for the Cubs.

When subsequent negotiations between Comiskey and Murphy over possession of Stack proved fruitless, the matter was referred to the National Commission, Organized Baseball’s supervisory body. Pending the commission’s decision, Stack continued pitching for the Logan Squares, throwing a one-hit, seven-strikeout, 1-0 gem at the Gunthers in mid-September.

In early October, commission chairman Garry Herrmann determined that Stack was the property of the Cubs.12 But Stack’s conduct in the affair, and particularly the contradictory affidavits that he had signed for the two clubs during the resolution process, prompted Herrmann to fine Stack $50 and declare him ineligible until he had reimbursed the $109 that the White Sox had expended in courting him.13 Stack also incurred the disdain of Sporting Life, which editorialized that it was “but one of many cases showing the lax notions of ballplayers regarding contractual and financial obligations and illustrates … the imperative of such a body as the National Commission to control players, to do justice to players and magnates alike.”14

By then, at age 22, Stack was a fully matured 6-feet-2½ and 195 pounds.15 His repertoire featured a heavy fastball and a good curve, plus a spitball, but he threw to contact, rarely amassing high strikeout totals. He showed well in spring training games, but the Cubs were rich in pitching. Along with returning staff stalwarts Mordecai (Three Finger) Brown, Orvie Overall, Ed Reulbach, Jack Pfiester, and Carl Lundgren, hot prospect King Cole was also in camp. Stack made the Opening Day roster but saw no game action during the first month of the 1910 season.

An astute judge of playing talent, Chicago field leader Frank Chance recognized the newcomer’s potential. But with an overabundance of pitching arms on hand and with no evident need of another, Chance sold Stack to the Philadelphia Phillies on May 26 without ever affording him the opportunity to pitch for the Cubs.16 Within a fortnight, Chance would have occasion to second-guess the move.

On June 7, 1910, Eddie Stack made his major league debut in Philadelphia’s National League Park (later Baker Bowl), squaring off against none other than his erstwhile club, the Chicago Cubs. Matched against veteran right-hander Harry McIntire, Stack held the Cubs scoreless in the first three frames. An Eddie Grant RBI then provided Stack with the only run he would get that afternoon. But it was enough, as the rookie sailed through the Chicago lineup, allowing only three harmless singles. Four walks (as compared to three strikeouts) provided the Cubs with additional baserunners, but Stack suppressed every mini-threat on his way to a complete game, 1-0 victory.

Back in Chicago, sportswriter Ring Lardner, tongue firmly planted in cheek, declared Stack a “traitor pure and simple” to his birthplace.17 Not to be outdone, the Philadelphia Inquirer compared Stack’s maiden big league appearance to the coming-out party of a high society debutante who “made quite a hit” and is expected to be a “social favorite this season.”18 In the short run, Eddie did not disappoint his newfound admirers, posting three more wins in quick succession. He hit a roadblock in early July, however, dropping a 5-0 decision in Boston. Worse yet, he was stricken with a severe case of ptomaine poisoning while there and was sidelined for more than a month thereafter.

When he returned to the mound, Stack was not the same pitcher, being hammered in starts against Pittsburgh and Chicago, the latter outing a 14-1 pasting on August 9 that proved satisfying to Cubs manager Chance. The result raised the season record of King Cole, the young prospect whom Chance had retained instead of Stack two months earlier, to a sparkling 11-2.19 Stack rebounded with a 7-3 victory over Cincinnati, but Sporting Life editor Frank Richter, a Philadelphian who personally covered the Phillies and A’s, was unimpressed. “Stack is showing no improvement due to indolence,” declared Richter in late August.20

Although not a problem drinker or malcontent, this would not be the only time when Stack was charged with being out of pitching shape or indifferent to his work. In the end, Stack finished the season with a pair of losses to close the 1910 campaign at 6-7 (.462), with a substandard 4.00 ERA in 117 innings pitched for a fourth-place (78-75-4, .510) Phillies club.

Notwithstanding his second-half slide, offseason newsprint placed Stack among the young hurlers upon whom the Phillies would be leaning in 1911.21 Yet once the season began, catcher-manager Red Dooin never handed the ball to Stack. He went instead with Grover Alexander, George Chalmers, Jack Rowan, Fred Beebe, and Ad Brennan as his starters in the early going. Stack did not get the call until May 19, by which time the Phillies were already 30 games into the schedule. In a rematch with Harry McIntire and the Chicago Cubs, Stack pitched well for seven innings before tiring. A combination of Philadelphia errors and a two-run Frank Schulte home run then sealed a 7-2 Cubs win.

For the next three months, the only time that the name “Eddie Stack” appeared in newsprint was when a New York City pickpocket divested him of an expensive gold watch fob at Grand Central Station. The incident provided sports page filler material from coast to coast.22 The modest crowds that attended Phillies games, however, often saw Stack throwing before games — until manager Dooin decided to start someone else. Or hurriedly getting his arm ready whenever a Phillies hurler was in trouble — but then usually returning to the bench. After two months of this, a frustrated Stack claimed to have set a new major league record for most innings thrown warming up.23

In mid-August, Dooin finally placed Stack in the Phillies rotation, and the youngster responded with three well-pitched complete-game victories in eight days. Used thereafter mostly in doubleheaders, Stack’s performance tailed off, but he did combine with George Chalmers on a 4-0 shutout against the Cubs in the second game of a September 20 twin bill (called after seven innings because of darkness). At season’s end, both Stack and the Phillies had nearly duplicated their previous year’s performance. For Stack, that translated into a 5-5 record with an improved 3.59 ERA in only 77 2/3 innings pitched; for Philadelphia, it was another fourth-place (79-73-1, .520) finish.

In December, a trade to the Brooklyn Superbas gave Stack a fresh start with a National League tail-ender in dire need of pitching help.24 But before joining his new club, Eddie had a domestic matter to attend to. In early January 1912, he and Kathryn Dwyer were joined in matrimony at Our Lady of Mercy Church in Philadelphia.25 In time, the birth of sons Edward (1913), John (1914), James (1916), and Walter (1922) would make the family complete.

In the interim, Stack reported to Brooklyn spring camp where expectations for him ran high.26 He got off quickly when the 1912 season started, capturing a 6-2 decision against his old Philadelphia club on April 26. But like Red Dooin, Brooklyn manager Bill Dahlen did not use Stack predictably. Almost three weeks passed before he logged another decision, pitching poorly in a 10-1 loss to St. Louis. And so it went for the rest of the season, Stack outings arriving at random intervals.

In his final start of the season, Stack posted a five-hit, seven-strikeout, 3-1 win over Philadelphia on September 27, played before a home “crowd” of less than 150 at Washington Park III. Pitching for a lousy (58-95, .379) seventh-place Brooklyn club, Stack’s 7-5 (.583) log was the only winning record posted by a Superbas hurler. He also registered a respectable 3.36 ERA in a career-best 142 innings pitched, but his strikeouts (45) to walks (55) ratio was poor.

Stack got off to another good start in 1913, winning his first three decisions. But as before, his outings were unpredictable as manager Dahlen used him on an as-needed basis. By late July, Stack had appeared in 23 Superbas games (nine starts) and fashioned a 4-4 record with an excellent 2.38 ERA for another non-competitive Brooklyn team. Then, on August 5, he was traded to back to the Chicago Cubs in exchange for a disgruntled Ed Reulbach.27

First-year Chicago manager Johnny Evers continued the practice of using Stack as both a spot starter and a reliever. Although he was pitching for a better club, Stack was less effective. In 11 games (seven starts) he won four times, including a 4-0 shutout of St. Louis in early September, but his ERA ballooned to 4.24. Combined between his two clubs, Stack finished the 1913 season with an 8-6 (.571) record and a 3.07 ERA in 138 innings pitched.

Over the winter, veteran National League umpire Hank O’Day was engaged as Cubs skipper, becoming the fourth major league manager whom young Eddie Stack would need to impress. And O’Day was anything but impressed with the poor physical condition in which Stack reported to spring camp or his easygoing, non-vigorous approach to preseason work. Chronic stomach trouble — likely an undetected duodenal ulcer that years later required surgery — retarded Stack’s efforts to get in shape or to be of much use to the club once the season began. As a result, manager O’Day used him sparingly, choosing instead to make Stack the Cubs’ semi-official exhibition game pitcher.28

By September, he had become so expendable that O’Day sent Stack home to Chicago rather than have him complete the club’s final road trip.29 Although with the Cubs for virtually the entire 1914 season, Stack appeared in only seven games (with one start), going 0-1 with a 4.96 ERA in 16 1/3 innings pitched.

In December, Roger Bresnahan, the ensuing Chicago manager, made public his intention to release a number of holdovers on the Cubs roster, including Stack.30 That release was officially announced in mid-February 191531 and brought the major league career of Eddie Stack to an end. In five seasons, he had made 102 game appearances, completing 24 of 60 starting assignments, and going 26-24 (.520) with a 3.52 ERA in 491 innings pitched. Over that span, he had yielded 469 base hits (good for a tolerable .258 opponents batting average), striking out 200 enemy batsmen while walking 188. The righty hitter had rendered his own cause little help with the bat, posting an anemic .108 career batting average (17-for-157) with only one extra base hit. His fielding had been so-so (.946 career percentage).

Only 27 and with relatively little wear on his pitching arm, baseball still afforded Stack career prospects. But rather than seek to revive his fortunes in the minors or to audition for the outlaw Federal League, Stack chose a more personally familiar course. He returned to the Chicago City League. As a hometown boy with a major league resume and a local fan favorite, Stack commanded up to $50 per game pitching on weekends. By mid-May, he was hurling for the Chicago Tigers.32 Later that summer, he settled into a permanent affiliation with the Marquette Manor club, one of the city league’s best.

Stack returned to semipro pitching the following summer, but also initiated some longer-term planning by enrolling in Chicago Normal School so that he could obtain the credentials needed for a state teaching license.33 He graduated from CNS in January 1917 and soon thereafter embarked upon a 36-year career as a Chicago high school teacher and administrator, primarily at Crane Tech High School.34

On weekends and during the summer through 1922, he continued pitching city league ball for Marquette Manor.35 Once he was too old to pitch, Stack remained in the game by umpiring local amateur, college, and semipro games. To counteract low pay and sometimes difficult working conditions, he subsequently formed a protective association for area umpires.36 In an emergency, he even filled in as first base umpire during an April 1934 Chicago Cubs-St. Louis Cardinals game.37

In his later years, Stack also did some freelance scouting for the Chicago White Sox and Detroit Tigers.38 He was also active with the Chicago Old-Timers Baseball Association.39

Stack remained a Chicago high school teacher/administrator until his retirement in 1956. Two years later, a fall in the bathroom at home sent him to Ravenswood Hospital on the city’s North Side. He died there of bronchopneumonia on August 28, 1958.40 William Edward “Eddie” Stack was 70. Following a Requiem Mass at St. Mathias Church, his remains were interred at Mount Carmel Cemetery in suburban Hillside, Illinois.41 Survivors included his widow Kathryn, his four sons, and siblings Irene Hummer, Margaret Fritts, and Leroy Stack.

Good-sized, athletically gifted, intelligent, and affable, Eddie Stack was a favorite of teammates, baseball fans, and the sporting press. Even the managers who declined to pitch him regularly liked Stack personally. In the end, as a teacher, area umpire, and family man, Eddie Stack led a socially useful life. But given his talents, his tenure as a major leaguer should have been more productive.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Joe DeSantis and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Source for the biographical information provided herein include the Eddie Stack file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Ray Schmidt, “Eddie ‘Smoke’ Stack,” The National Pastime, No. 17 (1997); US Census and other governmental records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Syndicated Hugh Fullerton column published in the Chicago Daily News, January 6, 1912: 9; Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Patriot, January 13, 1912: 14; and elsewhere.

2 The other Stack children were Johanna (born 1879 but did not survive childhood), Margaret (1882), Irene (1885), and Cornelius Leroy (1893).

3 As recounted by Brooklyn sportswriter Thomas S. Rice in “Players Who May Make the Superbas Champions: No. 6 — William Edward Stack,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 25, 1912: 12. For more detail on Stack’s time at St. Viator, see Ray Schmidt, “Eddie ‘Smoke’ Stack,” The National Pastime, No. 17 (1997), 121-124.

4 Per Schmidt, 121. St. Viator shortstop and Stack teammate Bernie Scheil later became a Chicago archbishop. The co-titleist was the Armour Institute of Chicago.

5 As reflected in box scores and game accounts published in the Chicago Inter Ocean in September 1907.

6 See “St. Viateur’s College Nine Which Produced Eddie Stack,” Chicago Tribune, July 9, 1909: 7, complete with team photograph. Note: St. Viateur was an alternative spelling of the school name.

7 Schmidt, 121.

8 A Joliet protest of Chicago City League raids upon its roster was unavailing. See “Semipros Face a War,” Chicago Daily News, June 25, 1909: 2.

9 See “Logan Squares Beat Gunthers,” Chicago Tribune, June 28, 1909: 10, and “Callahan’s Recruit Wins Game,” Chicago Daily News, June 28, 1909: 2.

10 “Logan Squares Beat Leland Giants, 5 to 0,” Chicago Inter Ocean, July 3, 1909: 22.

11 As reported in “Cubs Acquire a New Pitcher,” Chicago Daily News, July 7, 1909: 1; “President Comiskey Buys Two Young Players for White Sox,” Chicago Inter Ocean, July 7, 1909: 4; “Eddie Stack Is in Demand,” Chicago Tribune, July 7, 1909: 9. See also, “Inter-Club Row,” Sporting Life, July 17, 1909: 1.

12 See “Cubs Get Eddie Stack,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 5, 1909: 4; “Ball Officials Give Eddie Stack to Cubs,” Joliet (Illinois) Evening Herald, October 5, 1909: 6. Because the matter involved an inter-league dispute, National Agreement rules required the recusal of American League president Ban Johnson and National League president Tom Lynch and a unilateral decision by commission chairman Herrmann.

13 Per “A Sample Case,” Sporting Life, October 30, 1909: 4.

14 Same as above. See also, Schmidt, 122.

15 Based on sources unknown, modern baseball reference works curiously list Stack as 6’/170 lb. Contemporary photographs plainly depict a larger man, and era newsprint and his TSN player contract card place Stack between 6’1½”/188 lb. and “a towering six-foot-three,” per “Local Jottings,” Sporting Life, June 11, 1910: 3. The 6’2½”/195 lb. vital stats provided herein have been adopted from the exhaustively researched Eddie Stack profile by Ray Schmidt, above.

16 As reported in “Stack and Mitchell Go,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1910: 7; “Notes of the Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, May 27, 1910: 14; and elsewhere.

17 R.W. Lardner, “Stack Is Traitor; Beats Cubs, 1 to 0,” Chicago Tribune, June 8, 1910: 12.

18 “Brilliant Coming-Out Party,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 12, 1910: 3.

19 Cole would finish the season with a 20-4 record and a NL-leading 1.80 ERA.

20 Francis C. Richter, “Philadelphia Pride,” Sporting Life, August 20, 1910: 5.

21 See e.g., “Young Pitchers to Help the Phillies,” Montgomery (Alabama) Advertiser, January 5, 1911: 8.

22 See e.g., Washington (DC) Evening Star, June 23, 1911: 16; Oakland Tribune, June 22, 1911: 17; Detroit Times, June 21, 1911: 13.

23 Per “Sporting Gems,” Montpelier (Vermont) Evening Argus, July 26, 1911: 6.

24 See “Brooklyn Gets Eddie Stack in Trade for Doc Scanlon,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 15, 1911: 24; “Timely Bits of Sport,” New York Tribune, December 16, 1911: 6. When Scanlan, a newly licensed medical doctor, refused to report to Philadelphia, Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets provided the Phillies with cash compensation instead.

25 Per State of Pennsylvania marriage records accessed via Ancestry.com.

26 See “Great Things Predicted for Eddie Stack,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 12, 1912: 20.

27 As reported in “Reulbach Traded to Dodgers,” Chicago Inter Ocean, August 6, 1913: 13: “Eddie Stack Traded for Big Ed Reulbach of the Chicago Cubs, Brooklyn Citizen, August 5, 1913: 4; “Reulbach Traded to Superbas,” Washington (DC) Times, August 5, 1913: 11; and elsewhere. The transaction also obliged Brooklyn to remit an undisclosed amount of cash to Chicago.

28 See “Eddie Stack and Charley Smith Had Pretty Soft Jobs with Cubs Last Year,” Dayton (Ohio) News, December 2, 1914: 12.

29 As reported by Oscar C. Reichow in “Cubs Split Even in Pair with Phillies,” Chicago Daily News, September 24, 1914: 1.

30 See e.g., “Bresnahan Plans to Release Five Players on Cubs,” Providence Evening Bulletin, December 1, 1914: 16.

31 See James Crusinberry, “Cubs Release Tommy Leach and 3 Others,” Chicago Tribune, February 14, 1915: B1.

32 See “Stack Holds Ideal Team as Tigers Win, 5 to 3,” Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1915: 12.

33 Per Schmidt, 123. A normal school was a teachers’ college.

34 Schmidt, 123.

35 See “Marquettes Cop by 7 to 1,” Chicago Tribune, June 26, 1922: 16, memorializing a five-hit Stack victory over the Chicago Giants.

36 Schmidt, 124.

37 Paired with Stack was veteran umpire Bill Klem who worked the plate during an unremarkable 9-4 Cardinals win.

38 Schmidt, 124.

39 The last discovered newspaper photo of Eddie Stack was taken at an Association banquet in February 1957. See Edward Prell, “Ump at Plate! Calls ‘Em Right at 39th Dinner,” Chicago Tribune, February 8, 1957: C4.

40 Per the death certificate in the Eddie Stack file at the GRC.

41 Per the death notice published in the Chicago Tribune, August 29, 1958: 16.

Full Name

William Edward Stack

Born

October 24, 1887 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

August 28, 1958 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.