Felton Snow

The 1981 made-for-television movie Don’t Look Back: The Story of Leroy “Satchel” Paige, opens with a scene at a game between the Dizzy Dean Major League All-Stars and the Satchel Paige Colored All-Stars.1 The first name to be announced for the starting lineup is Felton Snow of the Baltimore Elite Giants. Many details from the movie are no doubt erroneous, but it was true that Snow played with Paige. In fact, Snow teamed with or managed almost every legend of the Negro Leagues who played during his two decades in baseball, from Paige, Oscar Charleston, and Josh Gibson to Jackie Robinson and Monte Irvin. The right-handed-hitting Snow played primarily as a third baseman, but he could be inserted nearly anywhere he was needed, whether it was the infield, outfield, or even on the pitching mound, and he often was slotted in by himself as a player-manager. For many years Snow had fallen into the dustbin of Negro League history, but in 2022 he was brought back into memory in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, and honored as one of the greats of the Negro Leagues.

The 1981 made-for-television movie Don’t Look Back: The Story of Leroy “Satchel” Paige, opens with a scene at a game between the Dizzy Dean Major League All-Stars and the Satchel Paige Colored All-Stars.1 The first name to be announced for the starting lineup is Felton Snow of the Baltimore Elite Giants. Many details from the movie are no doubt erroneous, but it was true that Snow played with Paige. In fact, Snow teamed with or managed almost every legend of the Negro Leagues who played during his two decades in baseball, from Paige, Oscar Charleston, and Josh Gibson to Jackie Robinson and Monte Irvin. The right-handed-hitting Snow played primarily as a third baseman, but he could be inserted nearly anywhere he was needed, whether it was the infield, outfield, or even on the pitching mound, and he often was slotted in by himself as a player-manager. For many years Snow had fallen into the dustbin of Negro League history, but in 2022 he was brought back into memory in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, and honored as one of the greats of the Negro Leagues.

Felton Snow was born on October 23, 1905, in Oxford, Alabama. His family had been in the town for generations; they likely obtained their name as slaves of the Snow family, one of the first White families to live in Oxford.2 (There is a Snow Creek that runs through the town.) Felton’s father, Jonah Snow, was born in post-Civil War Alabama, and in 1898 he married Claudia Johnson. Felton was the second of seven children for Jonah and Claudia, and the first son. After their last child was born in 1917, Jonah and Claudia separated, and Felton and two sisters moved with their mother to Louisville. The other siblings stayed with Jonah or other relatives in Alabama for a time but most eventually moved to Louisville. Jonah soon remarried and worked for years as a grocery deliveryman.

Felton quit school at age 14 and went to work to support his mother, who worked as a laundress in Louisville. When not working jobs as a porter or delivery boy, he found time to play baseball. He likely played for city teams in Louisville in his teens and into his 20s; his name began to appear in print in 1926.3 He played parts of the next few years with one of the top Negro league teams in Louisville, the White Sox, and with other semipro and minor Negro-league teams around the city and across the Ohio River in Indiana. Various box scores show that Snow moved all over the infield and outfield. During the early part of his career, Snow married Elnora Calloway in 1927; however, according to Louisville city directories, they were divorced by 1933.

Snow joined the ranks of major leaguers when he suited up for the White Sox in 1931. By that season, the team was a member of the Negro National League, one of the circuits considered a major league by Major League Baseball as of 2020. He played with the Louisville Black Caps in 1932, but at the end of July, the team abruptly disbanded,4 and Snow joined another team in Louisville, the Red Sox, to finish out the season.5 As the Red Sox prepared for the 1933 campaign, they looked forward to having a strong team with Snow and other Louisville players like Sammy Hughes and Willie Gisentaner on the roster. Instead, before spring training started, those three players and others headed south to Nashville and joined Tom Wilson’s Elite Giants of the Negro National League.

With the Elites, Snow blossomed into one of the top third basemen in the Negro Leagues. Standing 5-feet-10 and weighing 155 pounds, the freckle-faced Snow was not a showy player, but “he handled himself well and could make all the plays … had a rifle arm … and although not a baserunning threat, was a smart base runner.”6 He hit only .258 in his first season with the Giants, but he developed into a dependable hitter and was later considered to be “the most dangerous batter on the team in the clutch”7 as he became one of the mainstays of Wilson’s teams. Besides dragging the Giants between Nashville, Detroit, Columbus, Washington, and finally Baltimore, Wilson also took teams all over the country to play in barnstorming sessions between league games and then to winter leagues during offseasons. Tours included sessions in the famed California Winter League, where teams of Black players competed with teams of White players. Snow made his first appearance in the CWL in 1933 and handled himself well in the circuit, batting .322 in 43 games.8

Snow played in the popular East-West All-Star Game in 1935, representing the Elite Giants, now of Columbus, Ohio. He entered the game as a pinch-hitter in the 10th inning and drove in two runs with a single off Luis Tiant as the West team fought to an 11-8 victory in 11 innings. Leading up to the game, the Chicago Defender advised readers to keep an eye on Felton Snow: “Don’t look for dash and flash when Snow walks out to third base. … But you’ll be looking at a spread-eagle infielder who makes the hardest chances look easy. You’ll be looking at a finished ball player.”9

In addition to playing league games, it was customary for the Giants to barnstorm across the country as the team traveled west for the California Winter League and then returned home. In 1934, playing as the Philadelphia Royal Giants, Wilson’s group swept a series from a team of minor-league all-stars headed by Frank Demaree. Wilson’s squad participated in a much more celebrated game in 1935 – a matchup in Los Angeles on Halloween day that featured Dizzy Dean against Satchel Paige. Snow managed two hits in the game, but Dean’s All-Stars won, 5-4.

After receiving over 7,000 votes for the 1936 East-West game, Snow switched sides to play for the East, since the Elite Giants had relocated to Washington, DC. He was again on the winning team as the East easily won, 10-2. Snow’s votes were split between the third-base and shortstop positions, so Judy Johnson started the game at third, but Snow entered as a replacement and contributed to the East victory with a hit, a run scored, and a stolen base. Snow annually ranked near the top of East-West voting over his career, but 1935 and 1936 were the only years he played in the games.10

After the 1936 season, Wilson again took a team on the road. He assembled a squad from the Elite Giants, beefed up with stars including Gibson, Paige, and Cool Papa Bell, and took them to the Denver Post Tournament, known as the Little World Series of the West, for teams not associated with Organized Baseball. Since Negro League teams were not connected to Organized Baseball (not by their choosing, of course), Wilson’s National Negro All-Stars were eligible to take part in the event. Snow played a limited role in the tournament after suffering a hand injury, but the team handily defeated all opponents and took home a $5,000 cash prize. The Denver Post Tournament was just one of the notable tournaments that Snow appeared in over the years. He also played in a 1936 tournament against the Rogers Hornsby All-Stars, as well as a series of North-South all-star games and an all-star tour of Cuba in 1938, among others.

After several years of instability, the Elite Giants found their permanent home when they moved to Baltimore in 1938, even though the press would still refer to them as the Nashville Elite Giants for the next few years. The team finished third in the Negro National League II (NNL2) standings that year. Wilson traded fiery team manager George Scales to the New York Black Yankees in February 1939 as he intended to bring former manager Candy Jim Taylor back to lead the team; however, when a deal with Taylor fell apart in March, Wilson was left scrambling to find a new manager before spring training began. The Pittsburgh Courier reported that Biz Mackey was to take over managerial duties,11 but this was likely an assumption based on Mackey leading the team in 1937 before Scales arrived. Baltimore newspapers, however, referred to “Manager Felton Snow” in articles in April,12 indicating that Wilson had instead given the role to Snow, which proved to be a wise choice.

After playing for the tempestuous Scales, the Elites welcomed the change to Snow, who was “calm and relaxed, able to get results without bullying or belittling his players,”13 and he earned the nickname Skipper. An official announcement naming Snow as the manager was seemingly never posted, leaving some newspapers thinking that Mackey was running the club. Mackey was traded in July to make room for young catcher Roy Campanella as part of a youth movement that Snow helped drive, leaving no question as to who was running the club. Baltimore had a sluggish start to the season but came on strongly after the roster overhaul in July. The Elites made the playoffs and then surprised both the Newark Eagles and powerful Homestead Grays to claim the 1939 NNL2 championship. The title helped Felton reach the status of a local celebrity back in Louisville, to the point that the city’s main paper, the Courier-Journal, made mention of him whenever his travels brought him back through the city.

Though he started managing at the age of 33, Snow became not just a team leader, but also a father figure to many of the younger players. He supported his players but also set curfews, disallowed cursing, and “would not tolerate any ball players two-timing their wives.”14 Snow helped to develop young Elite Giants like Campanella and Junior Gilliam. When Snow took over as manager, Campanella was only 17, and overseeing him could sometimes present a challenge. Campanella’s roommate on the road, William Barnes, later recalled in an interview how he and Campy would return to their hotel room and be in bed just before Snow’s 11 o’clock curfew, fully dressed, then “no sooner than [Snow] left, we was out of the bed and gone.”15

Some of Snow’s dealings with his players influenced his thoughts on a popular topic of discussion: the integration of the White major leagues. When asked in 1939 about the possibility of Black players joining the majors, Snow was not sure it was the best idea at that time: “I don’t know that it would be a good thing, we’ve got so many guys who just wouldn’t act right. Some of these fellows who are pretty good on the diamond would give you a heartache elsewhere. … We have good players, yes. And some of them would certainly qualify, but it is a task finding the right combination.”16 Snow’s comment about finding the right combination was almost prophetic when Branch Rickey later signed Jackie Robinson to play for the Dodgers.

Even with additional managerial duties, Snow continued to play at a high level. In 1940 he hit .319 and slugged at a .414 rate for the Elites, his finest season statistically outside his 1934 campaign. The pinnacle of Snow’s 1940 season was managing the East squad to an 11-0 victory in that year’s East-West Game. Josh Gibson and other stars had jumped to Mexico to play and were not in the game, but Buck Leonard still provided some fireworks with three hits, three RBIs, and two stolen bases.

Although known for his calm demeanor, Snow could get fired up when the situation dictated it. In 1942 he was fined $25 and suspended for three days after he made contact with umpire Fred McCrary following a called ball in a July game versus the New York Black Yankees. He reportedly had to be escorted off the field by police after letting his temper flare over the call. It is uncertain if the ruling was enforced, as Snow was back in action a few days later when he penciled himself in as the starting pitcher in the second game of a doubleheader against the Cuban Stars. The 1942 season overall was an eventful one for the Elites. It was rumored that stars Sammy Hughes and Roy Campanella had a tryout scheduled with the Pittsburgh Pirates, but the tryout may have been overblown by the media, and it never took place. Later that year, Campanella and Hughes were fined and suspended by Wilson after leaving the Giants in the middle of a pennant race to play in an exhibition game for another team. Campanella left the team to play in Mexico, and the Giants ended the season in second place in the NNL2. Snow’s play suffered as well, and he hit only .222 for the year, one of his lowest season averages to date.

With fears of a possible World War II draft notice in 1943, Snow was given a break from managing duties.17 Control of the team was handed back to George Scales, who had returned to play for the Elites in 1940. Losing Campanella, Pee Wee Butts, and Wild Bill Wright to Mexico, and then losing Sammy Hughes to the military draft severely weakened the Baltimore lineup. The draft also claimed members of the Elites’ pitching staff,18 and the depleted squad finished with a disappointing 18-26-3 league record that put them in fifth place in the seven-team NNL2. Snow returned to the managerial post in 1944 and rebounded with a .320 average, his best since 1940. The club improved but still had a losing record of 34-38 for the year, and Baltimore fans were tiring of seeing their Elite Giants annually finish behind the Homestead Grays. Team business manager Vernon Green later explained, “Snow did the best he could with the material at hand and we can see no reason to change managers.”19

Wilson and Green kept Snow as their captain, and he led Wilson’s American All-Stars team that played in the Venezuelan league for the 1945-1946 winter season. Jackie Robinson was on the team, but he left early to join Branch Rickey and the Brooklyn Dodgers. In a February 1946 interview, Snow discussed how Robinson might perform in the majors. He appreciated Jackie’s abilities but thought he would need experience and noted, “In time, he will probably develop into a top-notch ball player because he has all the makings, but he needs to know the brain work and strategy that goes into playing shortstop.”20

Like everyone else, Snow knew the importance of Robinson’s signing, but he still may have had reservations about how the experiment would work. In Roy Campanella’s biography, Snow was quoted as observing, “I just don’t know how it’s gonna work. … How’s he gonna travel with them, and who’s he gonna room with? And how about when they play exhibition games in the South or during the regular season in Baltimore?”21

The Elites got off to a fast start in 1946, and Snow was rewarded with coaching duties in that year’s East-West Game. During his hiatus from the Elites for the game, however, a fight broke out in the Elites’ clubhouse between Joe Black, rookie Gilliam, and three Puerto Rican team members.22 The Hispanic players, Tite Figueroa, Luis Villodas, and Felix Guilbe, immediately quit the team (Villodas and Guilbe returned the next season.) Baltimore had already suffered the loss of Campanella, who had joined Robinson as a member of the Dodgers organization, and the Elites’ season continued to go downhill. They finished in second place but were 12 games behind the champion Newark Eagles.

Wilson had stood by Snow for years, but he decided to shake things up for 1947. He reassigned Snow to manage the Elites’ minor-league affiliate in the Negro Southern League, the Nashville Cubs, and selected Wesley Barrow as the new manager for the Giants. Wilson died that May, and Vernon Green took over the club. One of Green’s first moves was to release Barrow in July and reinstate Snow. Although he had played regularly with the Cubs, Snow scaled back his playing time for the Giants and placed himself in only three league games. The team finished third, and Snow was again sent to Nashville for 1948. Snow had one last highlight as a player when he went 5-for-5 in an August 1947 game for the Cubs.

Snow joined a different organization for the first time in over 15 years when he piloted the New Orleans Creoles in 1950. Interestingly, one of the players on his team was Toni Stone, the groundbreaking female player of the Negro Leagues. He drew some attention from clubs looking for a manager after 1950 but did not manage again. Much is written about the legendary players of the Negro Leagues who never had a chance to play in the integrated White majors, and rightly so. What sometimes is forgotten is that, after the National and American Leagues finally admitted Black players, it took many more years before the teams hired Black managers and coaches. As the top players of Blackball began to jump to opportunities with major-league teams, Negro League teams started to fold, and the number of coaching positions dwindled. Snow could have been a boon to the coaching staff of any team in Organized Baseball, but, as he reflected on the situation, he acknowledged, “I guess I was born 30 or 35 years too early.”23

Snow returned home to Louisville, where he joined the work force and helped to coach local teams. In 1958 he was cutting grass at a factory where he was employed and suffered a devastating injury when he fell into a ditch and the running lawn mower turned over on him.24 He recovered from the injuries and returned to the working world, now cleaning up and performing maintenance at a barbershop and retail strip in St. Matthews, a city in the Louisville area. Snow became a respected and beloved member of the community. SABR member Ken Draut and Kentucky Sports Hall of Fame board member Bill Malone, among others, during their childhood in the area looked to “Mr. Snow” for advice on playing ball, and they intently listened whenever he brought out his scrapbook and described articles and mementos from his playing days. For many people he was more than a local personality. Greg Galiette, president of the International League’s Louisville Bats in 2023, was one of those boys upon whom Snow had a special impact. Galiette related that, when his father was dying from cancer, Snow came around and helped with chores around the house and even played catch with the young boy.25 To show appreciation for Snow, a St. Matthews Little League team was named for him for over 20 years.

In his retirement, Snow enjoyed watching games on TV and attending an occasional game near his home. He once related an amusing anecdote about attending a game when Louisville native Pee Wee Reese was coaching his son’s Babe Ruth League team. Reese’s team had men on first and second when the batter hit back to the pitcher, setting up an easy double play. Reese shouted from his position in the third-base coach’s box for the opposing pitcher to throw to third base. The pitcher threw to third before realizing nobody was covering the base. Reese was ejected from the game, much to the entertainment of Snow and others in the stands.26

After more than three decades as a single man, Snow remarried in 1967 but enjoyed only seven years with his bride, Annie Mae Adams, before he died in 1974 from an apparent heart attack. Snow had a stepchild from each of his two marriages, but no children of his own. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Louisville’s Eastern Cemetery for nearly 50 years until 2022, when SABR’s Pee Wee Reese Chapter led an effort to honor him with a proper gravesite monument. Snow’s life was also celebrated by the Louisville Bats in a ceremony before their game on September 2, 2022.27 Several of Snow’s family members were in attendance to see his jersey number 2 formally retired by the team.

Acknowledgments

The University of Louisville library provided access to archives of the Louisville Leader newspaper.

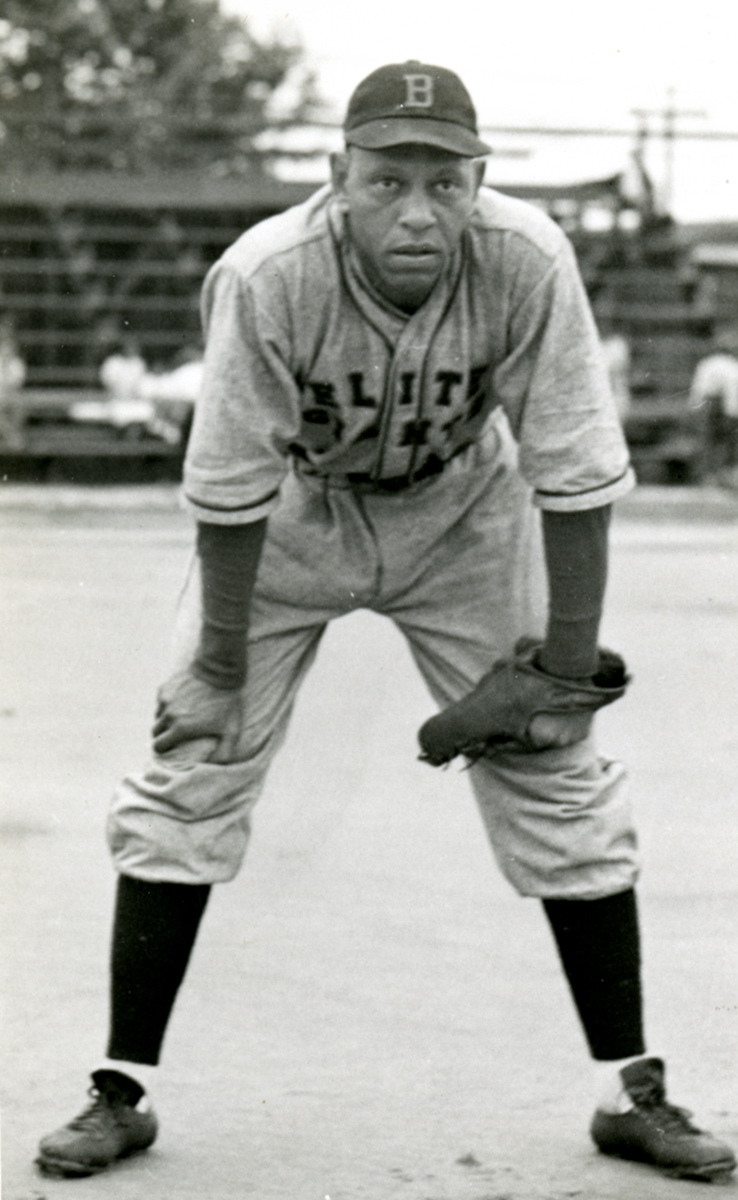

Photo credit: Felton Snow, Temple University’s Mosley Collection.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the authors used SABR.org, Newspapers.com, and Newspaperarchive.com.

Snow’s Negro League statistics were obtained from the Seamheads.com Negro League database.

Genealogical and family history was obtained from Ancestry.com.

Box scores for the East-West games were obtained from retrosheet.com.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame provided Snow’s player questionnaire card.

California Winter League teams and standings were obtained from http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/California%20Winter%20League%20Standings%20(1910%20-%201947).pdf.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball: 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007).

McNeil, William. Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside of the Negro Leagues, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2007).

Notes

1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yWWOHIDIYws.

2 https://wc.rootsweb.com/trees/360650/I11479/-/individual.

3 “First Standards to Play Hustlers,” Lexington (Kentucky) Herald-Leader, August 29, 1926: 6.

4 “Louisville Quits Southern League,” Chicago Defender, July 30, 1932: 9.

5 There were reports of the Black Caps playing in August and September, but this appears to be the remnants of the Black Caps that joined another local outfit, the Louisville Red Birds. The team seems to have had game reports filed under both names. Both teams have manager Jim Brown mentioned in articles.

6 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1994), 730.

7 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 36.

8 William McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 260.

9 “Expect 30,000 at All-Star Game,” Chicago Defender, August 10, 1935: 14.

10 Larry Lester’s East-West book shows Snow in the East team picture for the 1942 game, but he was not listed in the box score for either of the two East-West games played that year. Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game: 1933: 1962, Expanded Edition (Kansas City: Noir-Tech Research, 2020), 203.

11 Cum Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 25, 1939: 14.

12 “Elites Giants to Have Many New Players,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 22, 1939: 22.

13 Neil Lanctot, Campy: The Two Lives of Roy Campanella (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 55.

14 Belinda Cole-Schwartz, An Inside View of Negro League Baseball: Told by Elite Giant, Don Troy (Meadville, Pennsylvania: Fulton Books, 2022), 59.

15 Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited: Conversations with 60 More Baseball Heroes (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2000), 90.

16 Sam Lacy, “Sepia Stars Only Lukewarm Toward Campaign to Break Down Baseball Barriers,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 5, 1939: 19.

17 Art Carter, “Weather Adds to Elite’s Problems as Camp Opens,” Baltimore Afro-American, April 17, 1943: 24.

18 Pitchers Jonas Gaines and Bill Harvey were lost to the military draft. Joe Black was also drafted but was assigned to service in Baltimore and was able to pitch occasionally.

19 Lanctot, 104.

20 “Robinson Lacking Only in Experience, Says Snow,” Los Angeles Tribune, February 9, 1946: 14.

21 Roy Campanella, It’s Good to Be Alive (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1959), 117.

22 Sam Lacy, “3 Puerto Rican Stars Quit Elites in Huff,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 24, 1946: 26.

23 Dean Eagle, “Press Box,” Louisville Courier-Journal, February 15, 1969: 17.

24 “Felton Snow Severely Hurt on His Job,” Louisville Defender, July 10, 1958: 1.

25 “Louisville Honors Former Infielder Felton Snow,” Batsbaseball.com, https://www.milb.com/news/louisville-honors-former-infielder-felton-snow.

26 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 3, 1971: 35.

27 Batsbaseball.com.

Full Name

Felton Snow

Born

October 23, 1905 at Oxford, AL (USA)

Died

March 16, 1974 at Louisville, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.