George Shuba

(Copyright Mike Shuba)

George Shuba’s story is in many ways that of an average ballplayer.

In seven years in the major leagues, his career batting average was .259, and he played in a total of just 355 games, never more than 94 in a season. Nearly a third of his at-bats were as a pinch-hitter.1 His career was just long enough to qualify for a major-league pension (he counted down the days until he knew he had the service time). He then returned to his hometown and worked for decades for the U.S. Postal Service, living an amiable but quiet life, more than willing to tell his baseball stories at speaking engagements throughout the area.

But he was at the right time and place for a sliver of immortality. Shuba played his entire career for the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1948 through 1950 and then from 1952 through 1955. His teammates included baseball greats like Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese, Roy Campanella, and, of course, Jackie Robinson. Roger Kahn’s book of amber recollections a generation later included catching up with Shuba in Austintown, Ohio, a suburb of his birthplace of Youngstown. Forever after, Shuba would be known as one of “The Boys of Summer.”

After that, as appreciation for Robinson grew and members of those 1950s Brooklyn teams started dying out, Shuba, always regarded as one of the nice guys of baseball, became even more beloved. He appeared at Dodgers reunions and various other places. For example, when a school inquired about George’s speaking fee, his son Michael, who scheduled his events, said that George didn’t take speaking fees for schools. Instead, the children surprised their guest with coupons for Wendy’s, whose chili he liked.2

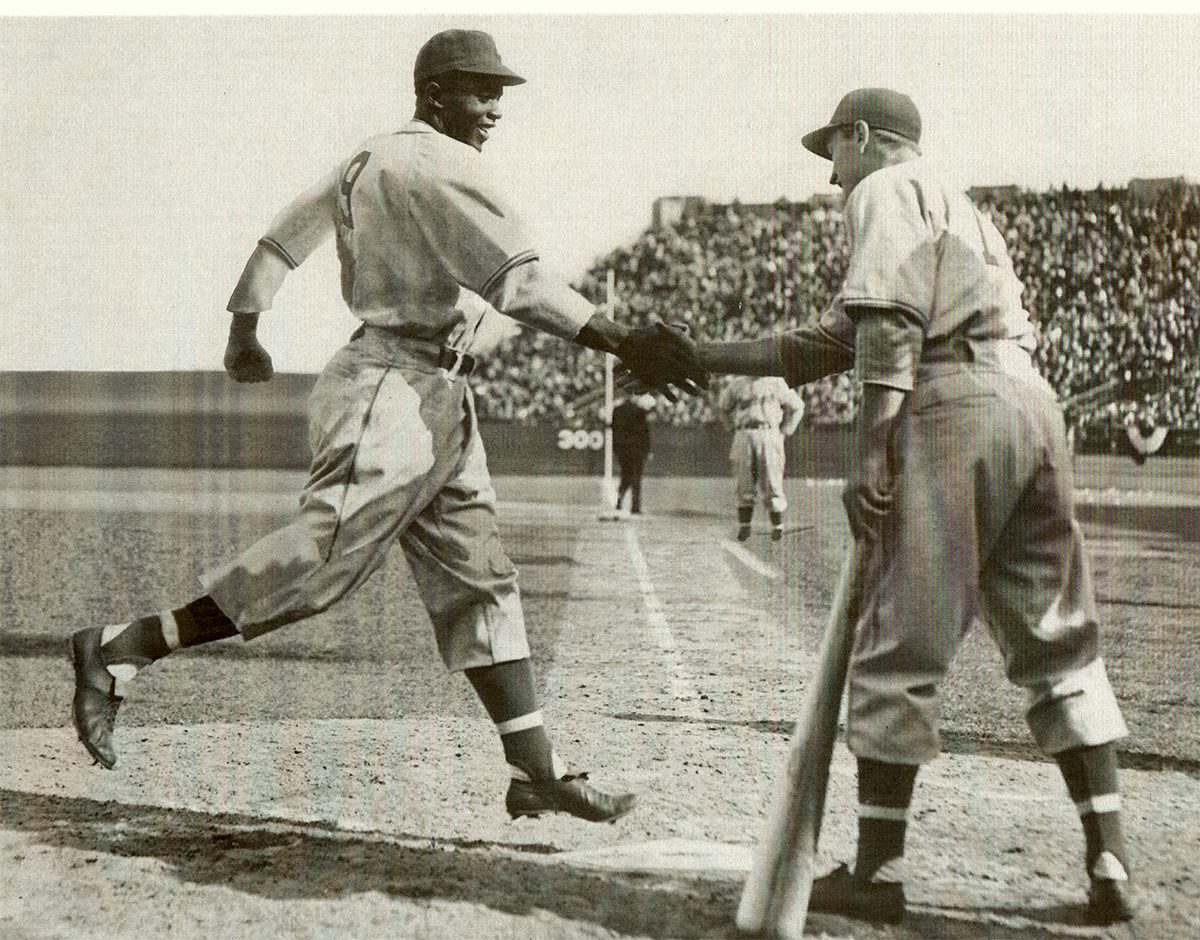

The photo of Shuba shaking hands with Robinson after he crossed home plate for a home run with the Montreal Royals on Opening Day in Jersey City in 1946 became more celebrated, and Shuba was only too happy to be recognized as the other guy in the picture.

“I wasn’t a great player, but I played with some of the greatest players in history,” Shuba said.3

George Thomas Shuba was born on December 13, 1924, in Youngstown, Ohio. The small city on the Ohio-Pennsylvania line quadrupled in population between 1890 and 1930.4 A confluence of factors combined to make it one of the great steel producers in the United States.

The Mahoning Valley was known for its coal seam, running under Brier Hill, a neighborhood that took its name from the plants that dotted its rolling hills. (The estate of David Tod, the governor of Ohio during the Civil War, had the same name.) And as anyone who has listened to Bruce Springsteen knows, there were also iron deposits.

Mills started to dot the banks of the Mahoning River, from large national conglomerates like Carnegie Steel to local companies, like the Tod family’s Brier Hill Steel Company, Youngstown Sheet and Tube, and Republic Steel. The mills required thousands of workers to keep the open hearths operating, and the Mahoning Valley became a mecca for immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. Each group formed its own enclave within the city, with its own church and its own funeral home.

The Slovaks settled on the city’s west side, and it was there that George Shuba was born, the youngest of the 10 children of George and Katharina (Puskar) Shuba. The couple had met in the Slovakian city of Spis; married in 1899, when both were 18; and departed in 1912 for America. The elder Shuba’s father was already there, working in coal mines in Eastern Pennsylvania.

As a boy, young George attended Holy Name School, also serving as an altar boy for Mass there. He spent his summers and spare time at nearby Borts Field, playing sandlot baseball — although in his autobiography, he told a story about playing baseball indoors one fall at a nearby grocery store that was under construction. Shuba would also occasionally go to nearby major-league games, and said his brothers bought him a train ticket and a game ticket for what turned out to be the game at Cleveland Stadium where Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak came to an end.

While at Holy Name, a nun boxed George’s ear, causing a perforated eardrum. The injury turned out to be a blessing in disguise, he said years later. As a result, Shuba, who turned 17 shortly after the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor led to the United States entering World War II, was ineligible for the draft. “Without it, I might be buried in Germany today,” he recalled.5

Shuba graduated from Holy Name and attended Chaney High School, embarking on a commercial course, taking typing, shorthand and other business classes. One of his contemporaries on the West Side and a fellow Chaney alumnus was Frank Sinkwich, who would go on to win the Heisman Trophy at Georgia in 1942, the same year Shuba graduated from high school.

When he was 15, Shuba had an eye toward escaping the steel-mill jobs that his father and some of his brothers had held — though one brother, Michael, went into the church and eventually became a Monsignor. In this pursuit, George acquired a habit that Kahn would chronicle decades later. He hung a knotted string from a pipe in the basement, and drilled a hole into one of his baseball bats and filled it with lead to make it heavier. He would then swing repeatedly at the string — 600 times a day, he recalled.6 Thus he developed bat speed (“Snap. Snap…Wrists,” as he coached Kahn) and discipline.

Shuba continued to play amateur baseball throughout the Youngstown area. One day in August 1943, a friend told him that the Dodgers were holding a tryout at Shady Run Field on the city’s South Side. The town had served as home to a variety of minor-league baseball teams, mostly in the Mid-Atlantic League (as well as a pro football team, the Patricians, in the days before the NFL’s formation). But it was also a well-known stop for major leaguers, thanks to a local mill worker who learned how to treat sprains, pulled muscles, and other injuries sustained on a baseball field. Every cab driver in Youngstown knew how to get from one of the city’s railroad stations to the North Side home of John “Bonesetter” Reese.7

Shuba made a brief appearance and took a turn at bat before he had to leave to go to another game in which he was playing. He said he didn’t think anything of the tryout, and continued to live at his family’s home and work for the Railway Express. However, on February 11, 1944, he received a call from Harold Roettger, a Dodger scout. Shuba initially thought it was a practical joke from his friends at one of the West Side gin mills, but it was on the level. The Dodgers signed Shuba for $150 a month and another $150 if he was still in the organization by July 1. “I would have given him $150 out of my pocket just to show him what I could do,” Shuba recalled later in his autobiography.8

His mother was less than encouraging. “She told me in Slovak there were too many others who could play better than I could,” Shuba told Dodgers rookies in 1955. “She wanted me to go to the mills.”9

Shuba was invited to Bear Mountain, New York, where the Dodgers were holding spring training with their top affiliate, the Montreal Royals. Following spring training, he was sent to the New Orleans Pelicans, at the time a Dodgers’ Class A affiliate, batting .196 in 19 games. He ended the season with the Olean Oilers (Class D), hitting .295 in 105 games.

In 1945, Shuba won another invitation to Dodgers spring training, which was again in Bear Mountain. Manager Leo Durocher had high hopes for him — in the infield. “He’s got a second baseman’s arm, fields well, has speed and shows real power,” Durocher said.10

From there, he was sent to Mobile, where he hit .320 in 137 games. Mobile is where he acquired his nickname. Bill Bingham, a sportswriter for the Mobile Press, the city’s afternoon paper, nicknamed him “Shotgun” because at the plate, he sprayed hits to all parts of the field.11 Shuba originally disdained the nickname — opposing players or fans used to ride him as “cap pistol” or “pop gun” when he struck out. Yet eventually he warmed to it, particularly when kids would ask for his autograph and ask him to sign with his nickname. (In fact, he signed autographs George “Shotgun” Shuba until the day he died.)

Also in Mobile, he acquired at least one famous fan. Hank Aaron recalled watching the Mobile Bears as a youth, “and my favorite on the team was a player named George ‘Shotgun’ Shuba.”12

With World War II over, the Dodgers resumed spring training in the South, and Shuba was again invited in 1946, where he met Jackie Robinson for the first time. The two were assigned to the Dodgers’ Montreal farm team, which would open the season on April 18, 1946, against the Jersey City Giants at Roosevelt Stadium. Robinson was batting second, with Shuba right behind him in the lineup. Robinson grounded out to shortstop in his first at-bat — but in his second time up, he hit a home run over the left field fence, his first hit as part of the Dodgers organization. Shuba was waiting for him at home plate and was excited for the moment — for Robinson and for himself.

“What were the odds that a kid like me, playing sandlot ball in 1943, would in three short years be shaking the hand of the first black player in modern times to integrate baseball? I’d say a million to one.”13

George Shuba, right, greets Jackie Robinson at home plate on April 18, 1946, in Robinson’s first game with the Montreal Royals at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, New Jersey. (Copyright Mike Shuba)

But Shuba’s time with the Royals was short. He played just 20 games with them, batting .200, before being sent back to Mobile, where he also spent most of the 1947 season. In 1946 at Mobile, he batted .290. The following season, in 152 games, he batted .288. One of Shuba’s Mobile teammates in 1947 was a lanky Brooklyn native who had spent his winters playing pro basketball. As it turns out, Chuck Connors was cut out for another career path: Acting.

Shuba tore through Southern League pitching to start the 1948 season, working his average up to .389 before he was called up to the Dodgers. He made his debut on July 2, 1948. Also new to the lineup that day was catcher Roy Campanella, who’d made his debut in April, but had spent most of the season to that date on the Dodgers farm team in St. Paul. “I had two singles and Campy added two singles and a double,” Shuba recounted in his autobiography. “Campy and I both seemed headed to the Hall of Fame. While Campy made it, my plans took a side step along the way.”14

Sliding into second base in August 1948, Shuba tore up his left knee. It was the start of an ongoing injury that would plague him throughout his baseball career and lead ultimately to surgery.15 In 161 at-bats with the Dodgers in 1948, Shuba had a batting average of .267. Following spring training in 1949, Shuba was sent to the minors again. He had originally been optioned to the Dodgers’ Fort Worth affiliate, but Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey sent him once again to Mobile, which had become his second home.

He appeared in just one game for the Dodgers that season and just 34 the following year. The abundance of talent the Dodgers had at that point made it difficult to break into the lineup — fellow outfielder Al Gionfriddo, who was also stuck in the logjam, called it a “dog-eat-dog business.”16 As long as Shuba had options, the Dodgers would keep using them.

In 1951, Shuba’s knee acted up, and at one point, he was in a cast. New York World-Telegram columnist Dan Daniel suggested that had Shuba been able to play in Brooklyn that season, his bat might have made the difference in helping the Dodgers stave off the Giants, who famously made up a 13-game deficit and won the pennant in a playoff series.17

1952 marked Shuba’s first full season — and his high-water mark — with the parent club. He appeared in 94 games, as an eye injury limited the availability of right fielder Carl Furillo. Andy Pafko spelled Furillo in right field, and Shuba played left field, hitting .305 with nine home runs, both career highs for him. Shuba actually got some votes for MVP that year, finishing in a tie for 31st in the voting. Following the 1952 season, he had knee surgery.18

In 1953, Shuba appeared in 74 games and hit .254, but his most notable achievement that season came in Game One of the World Series. With the Dodgers trailing 5-1, Gil Hodges led off the top of the sixth inning with a home run to left field at Yankee Stadium. Furillo flied out, and Billy Cox singled. Pitcher Jim Hughes was due up, but manager Chuck Dressen called in Shuba to face the Yankees’ Allie Reynolds. The Super Chief threw a fastball high and away that Shuba said he barely saw for ball one. He took a curve for a called strike. “Hey, Shuba, it’s tough seeing up here, isn’t it,” Yankees catcher Yogi Berra told him. “Yogi, don’t bother me,” Shuba replied. “I gotta get a base hit.”19 Shuba swung at a fastball inside for strike two, and on the next pitch swung on what he thought was a backdoor curve and hit a line drive to right field. Hank Bauer couldn’t get a glove on it, and it cleared the fence for just the second pinch-hit home run in World Series history — and the first by a National Leaguer.

In 1954, Shuba was limited to 45 games and hit an abysmal .154. He was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism.20 He was still holding on to try to get vested in the pension plan and remained with the club in 1955. At one point, Shuba was placed on waivers. Apparently he was nearly sold at the deadline to Kansas City, but at the last minute, manager Walter Alston and GM Buzzie Bavasi pulled him back.21

Shuba made the World Series roster, and in the clinching Game Seven, was called on to pinch hit for second baseman Don Zimmer. Outfielder Jim Gilliam replaced Zimmer at second base, and Sandy Amorós came in to play left field. With two on, Berra swung and sliced a shot to left field. Amorós raced to the line, caught the ball and threw to Hodges to double up Gil McDougald. It was a difficult play for the lefty-throwing Cuban, whose glove was on his right hand. It might have been impossible for the righty Gilliam, who would have had to reach his gloved left hand across his body to make the catch.

Shuba’s major-league career ended on a high note when Brooklyn won the 1955 World Series. The following year, he returned to Montreal, where his teammates included a young Sparky Anderson. Shuba batted .243 in 113 games with Montreal in 1956.

In April 1957, Montreal sold Shuba’s contract to Memphis in the Southern League, which prompted him to announce that he was quitting and returning to Youngstown.22 Soon, however, he reconsidered and joined the Chicks.23 He played in 74 games in 1957 for Memphis (a Cubs affiliate). In July, when he was sent again to Fort Worth, he really did call it a career.24

Shuba’s great misfortune in his baseball career is that he might have been born too soon. His knee injuries made playing the field more and more difficult — as Kahn discovered, Shuba was sensitive to perceptions that his defense was suspect — but his bat remained an asset.

“George was a pure hitter and he would have made a super designated hitter today,” said former teammate Carl Erskine. “He could come off the bench cold any time and hit a line drive.”25

After retiring from baseball, Shuba returned to Youngstown and with a partner opened a sporting goods store. The timing was less than fortuitous, he recalled, since the store opened shortly before the national steel strike of 1959. He worked for a local insurance firm for a while before going to work for the U.S. Postal Service. His clerical classes at Chaney High School served him well as a stenographic aide to the Postal Inspectors unit at the main post office in downtown Youngstown.

A bachelor in his playing days, Shuba met Kathryn Forde, and the two married on September 8, 1958. They had a son, Michael, and two daughters, Mary Kay and Marlene.26

In the early 1970s, Roger Kahn came to Mahoning County to catch up with Shuba, one of 13 former Dodgers players he interviewed for The Boys Of Summer. Kahn’s book, as much a coming-of-age story as a baseball book, told a bittersweet tale, reflecting on his childhood and his relationship with his family. The men he’d admired as a fan and then as a young journalist had reached middle age, revealing their own struggles with health, family, and finances (the book’s title was taken from a Dylan Thomas poem, which begins, “I see the boys of summer in their ruin…”). Kahn tried to bathe the stories in as much pathos as he could — and he had more than enough to work with in this regard. Snider’s investments had failed. Campanella was paralyzed and his marriage was disintegrating when his first wife died. Robinson was battling diabetes and Gil Hodges had already had a heart attack — both would be dead within months of the book’s release.

But Shuba’s story was a little different. He was living a quiet suburban life and more than happy to raise his family. “This is the real part of my life,” he told Kahn.27 After Kahn told Shuba how much he admired his swing, Shuba brought him to the basement and showed him his secret, the string and the bat. “I swung a 44-ounce bat 600 times a night, 4,200 times a week, 47,200 swings every winter.”28

Shuba was an active retiree. He would regularly appear at Dodgers reunions, making a trip to Los Angeles in 2005 for the 50th anniversary of the only world championship won in Brooklyn, and he made a trip to Dodgertown in Vero Beach in 2008, the last time the Dodgers used the facility for spring training.

(Copyright Mike Shuba)

A large collection of his memorabilia went up for auction in 2006. Shuba said he wanted to do so while he could still remember all the memorabilia and establish its provenance. He wasn’t particularly sentimental, recalling that not only did he rarely wear his 1955 World Series ring, his wife would even yell at him for not wearing his wedding band.29 But there was one exception, Mike Shuba told New York Times writer Dave Anderson: A picture framed and hanging above the easy chair in his living room in Cornersburg. “It’s the photo of him with Jackie Robinson in Jersey City,” Mike Shuba said. “It’s been there for 40 years.”30

In 2007, Shuba published his autobiography. What began as a set of typewritten recollections for his children and grandchildren turned into a full-fledged book, My Memories as a Brooklyn Dodger.31

George Shuba died on September 29, 2014, at the age of 89. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery on Youngstown’s West Side — not far from the house in which he was born, Borts Field — renamed for him in 2007 — and his alma mater, Chaney High School. Kathryn Shuba died in 2016.

In 2019, plans were announced for a statue depicting Shuba and Jackie Robinson’s famous handshake, to be displayed on Front Street in downtown Youngstown. The dedication is planned for April 18, 2021, the 75th anniversary of when the handshake occurred.32

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bruce Harris and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Kahn, Roger. The Boys of Summer (New York City: Harper, 1972).

Shuba, George, with Greg Gulas. My Memories as a Brooklyn Dodger (Youngstown: City Printing, 2007).

Baseball vertical file, Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County.

George Shuba file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

Notes

1 Roger Negin, “The Joys of Summer,” July 6, 2005, Elyria Chronicle-Telegram, baseball file, Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County.

2 Dave Anderson, “A Simple, Silent Moment in Baseball History,” Sports of the Times, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/17/sports/baseball/a-simple-silent-moment-in-baseball-history.html.

3 “’Shotgun’ Shuba Not Forgotten,” source unknown, baseball file, Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County.

4 https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Youngstown,_Ohio.

5 John Kovach, “Dedication, Help Took Area Man to the Top, Valley Voice, July 1-7, 2005, 35. Baseball file, Public Library of Youngstown and Mahoning County. The Valley Voice was a weekly newspaper put out by personnel of the Vindicator while the Newspaper Guild was on strike.

6 Ed Shakespeare, “’Shotgun’ Shuba Returns to Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Paper, July 23, 2008, https://www.brooklynpaper.com/shotgun-shuba-returns-to-brooklyn/.

7 One of Reese’s earliest patients was another Youngstown native, Jimmy McAleer, who not only recommended the Bonesetter to other players, but also recommended Billy Evans as a potential major league umpire to Ban Johnson. The Evans family came to Youngstown so Billy’s father could work at the Carnegie Steel mill.

8 Shuba, My Memories as a Brooklyn Dodger, p. 21.

9 Bill Roeder, “Shuba Gets Cheers, Only as Hitter,” New York World-Telegram, March 5, 1955, Shuba clip file, Baseball Hall of Fame.

10 Gus Steiger, “Shuba is Tabbed Future Dodger,” April 3, 1945, Shuba clip file, Baseball Hall of Fame.

11 His 1953 Topps baseball card incorrectly states he received the nickname for his “powerful throwing arm,” something Shuba laughed about decades later.

12 “’Shotgun’ Shuba Not Forgotten.” On page 202 of his autobiography, Shuba refers to an article written by Fred Claire saying this.

13 Dave Stubbs, “Greeting History at Home Plate,” The Montreal Gazette, April 18, 2006, reprinted Oct. 1, 2014, https://montrealgazette.com/sports/obituary-george-shuba-was-first-white-player-to-shake-jackie-robinsons-hand-with-montreal-royals.

14 Shuba, My Memories as a Brooklyn Dodger p. 67

15 Roscoe McGowen, “Hats Off…!” The Sporting News, August 20, 1952: 17.

16 Richard Goldstein, “Al Gionfriddo, 81; Remembered for ’47 Catch,” New York Times, March 16, 2003, https://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/16/sports/al-gionfriddo-81-remembered-for-47-catch.html.

17 Dan Daniel, “Daniel’s Dope,” New York World-Telegram, November 15, 1952, Shuba clip file, Baseball Hall of Fame.

18 Dan Daniel.

19 Shuba, My Memories as a Brooklyn Dodger, p. 99

20 “Dodgers’ Medic to See Shuba,” New York World-Telegram, November 9, 1954, Shuba clip file, Baseball Hall of Fame.

21 “Change Mind Before Sale,” New York World-Telegram, July 1, 1955, Shuba clip file, Baseball Hall of Fame.

22 “Shuba Hangs Up Glove,” The Sporting News, April 17, 1957: 40.

23 “Shuba Reconsiders, Joins Chicks,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1957: 29.

24 “Shuba on Chicks’ Retired List,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1957: 41.

25 “’Shotgun’ Shuba Not Forgotten.”

26 Kathryn Shuba obituary, http://hosting-12792.tributes.com/obituary/show/Kathryn-A.-Shuba-103963422.

27 The Boys of Summer, p. 238.

28 The Boys of Summer, p. 241.

29 Ben Sobieck, “Shuba’s Treasures Recall 1955 Series Win.” Sports Collectors Digest, https://sportscollectorsdigest.com/auctions/shubas-treasures-recall-1955-series-win.

30 Dave Anderson, “A Simple, Silent Moment in Baseball History,” The New York Times, April17, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/17/sports/baseball/a-simple-silent-moment-in-baseball-history.html.

31 When I interviewed George for a magazine story, not long after the book came out, he gave me a copy. Of course, he autographed it George “Shotgun” Shuba, and said with a wink, “It might not be worth much now, but in a few years…it should be worth even less.”

32 Robinson-Shuba project, https://robinsonshuba.org/.

Full Name

George Thomas Shuba

Born

December 13, 1924 at Youngstown, OH (US)

Died

September 29, 2014 at Youngstown, OH (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.